Paul DeNicola is Principal at the Governance Insights Center, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on his PwC memorandum.

As companies plan for a post-pandemic economy, and continue tackling social issues, they must also contend with rapid business transformation. Talent management is more critical than ever—and so is director oversight.

Corporate directors have traditionally focused their talent management efforts on the C-suite, leaving oversight of the broader workforce to senior executives. But the pandemic, pressure to advance diversity and inclusion efforts, and the astonishing pace of business and digital change have made it critical for boards to provide greater oversight of talent management at multiple levels of the organization.

Rethinking talent

Providing oversight of a company’s top talent has long been a core responsibility of corporate boards. They play a critical role in hiring and firing the CEO, evaluating the performance of top executives, developing leadership succession plans, and ensuring their companies have a robust pipeline of talent to execute company strategy.

Traditionally, directors have focused their talent management efforts on the C-suite, leaving oversight of the broader workforce to senior executives. But many boards have come to understand that a strategy is only as good as a company’s ability to execute it. And strong execution requires talented people at all levels of the organization—particularly when most companies are reinventing themselves amid widespread disruption and planning for a post-pandemic world.

These days, the ability to attract, develop, and retain the best talent has become a critical business differentiator. Yet it is a challenge. In a recent survey, CEOs cited the low availability of key skills as one of the top threats to business. As widespread transformation continues to drive demand for workers with new skills, not having a comprehensive plan for acquiring and developing these workers can hurt a company’s ability to grow and innovate.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only compounded the need to rethink talent management. The initial focus was the immediate crisis of ensuring workers’ health and safety and staying financially afloat. Now companies are looking at how COVID-19 has changed their business and working models and what that means for their future talent strategies.

Some of the pandemic’s biggest long-term impacts on the workforce include much higher numbers of employees working remotely, less corporate travel, and reduced office space. This gives companies greater flexibility to recruit talent from anywhere. It also means they need to ensure they have the right technology and corporate culture to support the shift to a more virtual work environment. The acceleration of digitization and business strategy changes required during the pandemic may also have a lasting effect on the type of talent companies need.

Aside from the implications of COVID-19, companies are also grappling with a social crisis that has heightened the focus on workforce diversity and inclusion (D&I). In November 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued a new rule expanding its human capital disclosure requirements beyond listing the number of employees. Under the new rule, companies must also disclose any human capital measure or objective they use to manage the business, including talent development, attraction, and retention. Because the new rule is principles-based rather than prescriptive, companies have latitude in fulfilling this requirement (for further guidance, see PwC’s New human capital disclosure rules: Getting your company ready).

As a result of all these changes, boards must play a larger role in ensuring their organizations have the talent they need to execute new strategies in a post-pandemic world and respond appropriately to the calls for greater workforce transparency.

Rising investor pressure

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, institutional investors began paying closer attention to talent management. Many have recently communicated specific expectations for public companies related to D&I. In support of these priorities, they are urging boards to become more involved in workforce planning and development. They are also pushing for more disclosure about that oversight.

Many investors believe that to understand the forces shaping their business and remain competitive, companies need to take action on D&I issues. Some cite research showing D&I is associated with greater innovation, better decision-making, and stronger company performance. As a result, they are looking to companies to promote D&I principles within their operations and be more transparent about those initiatives.

For example, State Street Global Advisors CEO Cyrus Taraporevala sent a letter to board members in January 2021 detailing three actions the firm would be taking to promote D&I efforts within the companies in its investment portfolio:

- Starting in 2021, it will vote against the chair of the nominating & governance committee at S&P 500 and FTSE 100 companies that don’t disclose the racial and ethnic composition of their boards.

- In 2022, it will vote against the chair of the compensation committee at S&P 500 companies that don’t disclose their EEO-1 Survey responses, which contain detailed workforce diversity data across ten job categories.

- Also in 2022, State Street will vote against the chair of the nominating & governance committee at S&P 500 and FTSE 100 companies that don’t have at least one director from an underrepresented community on their boards.

Along similar lines, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink stressed the importance of a diverse workforce in his January 2021 letter to CEOs. Companies that lack diversity are failing to “draw on the fullest set of talent possible,” Fink said. He called on companies to include disclosures on talent strategy that “fully reflect your long-term plans to improve diversity, equity and inclusion, as appropriate by region.” He noted BlackRock’s pledge to hold itself to the same standard.

On behalf of the New York City Retirement Systems, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer has also joined the chorus of large investors demanding greater transparency. In August 2020, he called on 67 of the S&P 100 companies to commit to publicly disclosing their EEO-1 reports in 2021. In his letter to those companies, Stringer said those that refuse to make this disclosure risk receiving targeted shareholder proposals or opposition to the directors’ election at their next annual shareholder meeting. Since then, at least 40 of those 67 companies have agreed to comply.

The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) has also expressed the need to raise the bar on human capital management and noted the board’s responsibility in the matter. According to its corporate governance principles, “Boards should have an active role in setting the company culture and oversight of the company’s approach to human capital management, which should include: employee wellbeing; health and safety; commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion; gender equality; employee development; providing a workplace free of sexual harassment and other forms of harassment; and promoting ownership and accountability.”

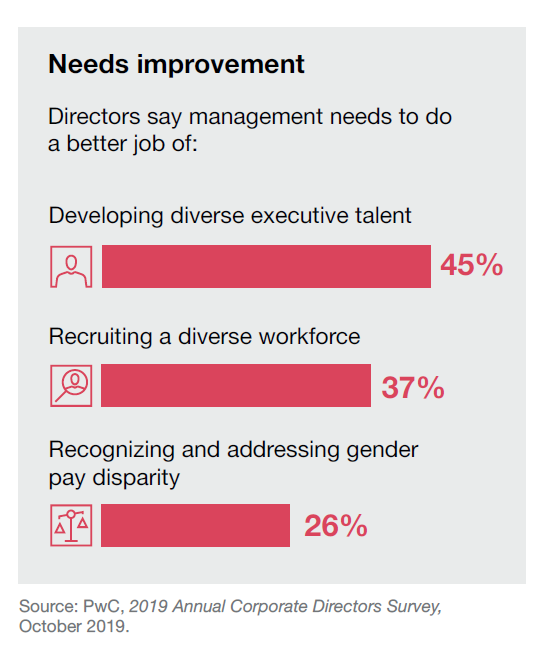

Given the SEC rule change and rising investor pressure, directors are taking a hard look at their company’s talent management. And they see room for improvement. Nearly half of the directors in PwC’s Annual Corporate Directors Survey say their companies are doing a “poor” or only “fair” job of developing a diverse pool of executive talent. Roughly one-third say they miss the mark on recruiting a diverse workforce and one-quarter say the same about addressing gender-related pay differences.

Three steps to better board oversight

Taking a more substantive role in talent management oversight isn’t easy. It requires boards to strike a balance between acting strategically to ensure the company’s strength without stepping into the role of management. Here’s a framework for maintaining a healthy oversight balance at three different levels of the organization:

1. The C-Suite

Directors are responsible for selecting and monitoring the performance of the CEO. As part of that responsibility, the board needs to hold the CEO and other C-level executives accountable for company performance on talent management. This has become even more important as CEO tenure has fallen to a median of five years, down from six years in 2013. As tenures get shorter, CEOs are under more pressure to deliver short-term results. Tackling longer-term initiatives such as upskilling the workforce and increasing diversity becomes even more challenging. So, boards must ensure that talent development remains a top management priority, despite the pressure to meet shorter-term performance targets.

When it comes to C-suite oversight, this can mean setting objectives related to:

- strategic talent management,

- upholding healthy and ethical corporate values to set the right tone at the top, and

- creating a diverse and inclusive culture.

Closely measuring executive performance in each area is critical, along with making it clear to the team that the board expects them to model proper workplace behavior.

2. Up-and-comers

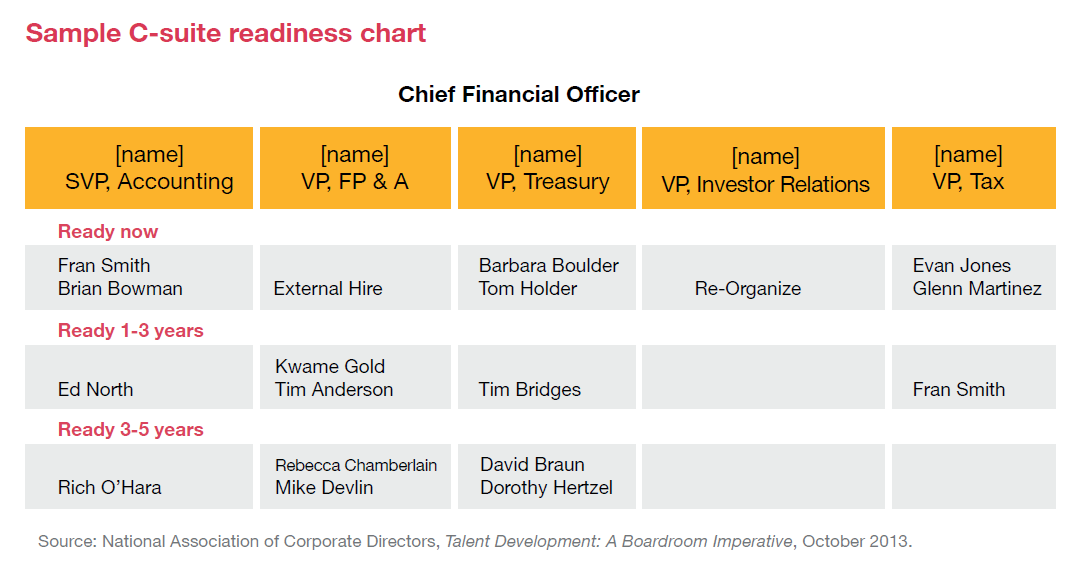

Boards need to ensure the company has a robust talent pipeline for all C-suite functions. They can do this by using a “C-suite readiness chart” (see chart below) that identifies senior executives who could assume those positions now and who might be ready one to five years in the future. In the meantime, they should take steps to get to know and assess the capabilities of these high performers by:

- having them present to the board on major initiatives,

- assigning them to work on special board projects,

- or inviting them to board dinners and other social events.

3. Middle management

Getting to know middle managers is particularly difficult for board members. At this level, the board can provide oversight by understanding the organization’s talent philosophy, culture, and talent needs for the future.

This includes:

- reviewing talent retention strategies and compensation programs to ensure they address issues like gender inequity and achieving diversity and inclusion goals,

- reviewing metrics that indicate whether the culture aligns with company strategy, and

- asking how management plans to address current and future skills gaps created by the adoption of artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, advanced analytics, cloud technology, and automation.

Board oversight in action

What tools does the board need to ensure that a company’s talent management approach aligns with corporate strategy? Here’s where to start:

1. Data

During the pandemic, board reporting shifted. Management sent boards more frequent and detailed human capital reports as they monitored workers’ health, safety, and productivity. Even after the crisis, boards can continue to use this data to spot warning signs and make better-informed decisions. A review of talent management-related key performance indicators (KPIs) can identify red flags and opportunities for improvement. Helpful data points include:

- high turnover and high-performer departure rates,

- unfavorable exit interviews (particularly those of high-performing employees),

- the race, ethnicity, and gender breakdown of the current workforce, new hires, the recently promoted, and resignations,

- positions that remain unfilled for long periods,

- succession plan failure rate (number of times management established a plan but ultimately hired someone else),

- low employee engagement scores (including an analysis of scores by diverse groups), and

- whistleblower complaints and lawsuits involving HR issues such as harassment and discrimination.

2. First-hand information

Aside from data, directors benefit from exposure to employees from as many levels of the organization as possible. Paying attention to employee sentiment and behaviors can identify areas of strength or concern. This can be done by:

- getting a sense of the tone at the top through observation and the use of quantitative metrics related to culture,

- observing interactions between management team members during board presentations to identify potentially unhealthy dynamics, such as an unwillingness to be candid,

- interacting with employees below the C-suite during social events, site visits, and board programs,

- using the company’s products and services to interact with frontline employees and get a sense of its customer service style, or

- reviewing employee engagement surveys and requesting reports and presentations on corporate culture.

3. Accountability

Focus from the board can ensure that developing and managing talent is one of a company’s top priorities. Directors should consider six actions as they look to provide greater oversight:

- Assign talent management responsibility to either the full board or a dedicated committee so everyone understands their roles and responsibilities. Talent oversight is often allocated to the full board, with committees overseeing certain aspects within their specific areas of oversight. Many boards choose to assign talent management oversight to a designated committee, usually compensation. Whichever structure the board adopts, the important thing is to make sure the allocation of responsibility is clear.

- Incorporate talent into strategy discussions. When assessing the viability of strategic initiatives, directors often focus on the financial implications of these decisions. That’s a big piece of it, but the board also needs to make sure the company has the right people to execute that strategy. The board can do this by requesting that management include a “talent component” in every new initiative they present to the board.

- Make talent management experience a selection criteria for new board members and highlight existing capability. Not every board needs a director with human resources expertise, but talent management skills can be beneficial. Directors who have managed companies, divisions, or regions can bring helpful talent management experience. Companies may wish to highlight this expertise among current directors in the company’s proxy statement.

- Elevate the chief human resources officer (CHRO) to a more strategic role and ask for regular updates. Many companies have elevated their human capital leaders, giving them greater responsibility for overseeing talent development and culture efforts. As a C-suite member, the CHRO should have a regular spot on the board’s agenda. Some boards have their CHRO present a talent review to the entire board once a year, with updates as needed. This talent review should also include a focus on diversity and inclusion efforts.

- Make talent management a KPI for executive compensation. Set specific people-development goals in areas like diversity and inclusion, as well as retention targets for new hires and high-potential performers to encourage leaders to place greater focus on talent issues.

- Ensure that diversity and inclusion efforts are embedded within the organization. This also requires management to provide appropriate reporting to the board on D&I goals and performance against those goals. The board’s efforts in the area are important too. Examining the board’s own diversity and approach to succession planning—and being transparent about those efforts—indicates a commitment to the cause.

Building talent for tomorrow

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent racial protests, new disclosure requirements, shortage of skilled labor, and astonishing pace of business and digital change are all weighing on companies. And they are the reasons boards need to shoulder greater oversight responsibility for talent management. Day-to-day talent development responsibilities, of course, remain with management. But directors can work to ensure their company’s approach to talent supports its long-term objectives.

When boards and management teams prioritize investing time and resources in human capital development throughout the organization, they are more likely to win the talent wars while becoming more resilient, agile, and innovative.

PwC perspective: communicating the board’s talent management approach in the proxy statement

Investors are increasingly interested in how boards approach talent oversight. As part of providing greater transparency to investors, consider the benefits of adding proxy statement disclosure on:

- how the board approaches its oversight of talent management,

- how often the board discusses talent management issues,

- how often these discussions include updates on the company’s diversity and inclusion efforts,

- how executive leadership is held accountable for driving change in diversity and inclusion in the organization through metrics or goals-based compensation, and

- how the board plans for management succession beyond the CEO.

How companies are approaching the SEC’s new human capital disclosure rule

Since the 1970s, the SEC has only required public companies to disclose one human capital metric in their financial statements: the number of employees. But after years of debate, the SEC expanded that requirement, recognizing the strong correlation between how companies manage talent and their long-term success. Effective November 9, 2020, public companies must also disclose the following in their Form 10-K and Form S-1 filings:

- a description of their human capital resources, and

- any material human capital measures or objectives the company focuses on in managing the business, such as those related to employee development, attraction, safety, engagement, and retention.

Because the SEC took a principle-based rather than prescriptive approach to writing the new rule, it doesn’t list the kinds of measures or metrics that companies must disclose. The SEC said this would enable companies to tailor the disclosures to their specific circumstances and allow disclosures to evolve as a company’s business changes over time.

Given the latitude in fulfilling this requirement, companies are likely to look to their peers to benchmark the kinds of information they’re disclosing. To identify the early trends, PwC reviewed more than 2,000 Form 10-Ks filed after the new rules took effect in November 2020. In that review, we found that:

- 89% of the filings included both qualitative and quantitative human capital disclosures, with many companies providing breakdowns of the number of employees by geography, job function, management level, and full or part-time, and

- 66% disclosed D&I information, up from 4% to 5% last year. The percentage was even higher among the largest public companies: 90% of the S&P 100 disclosed D&I information. Those that included D&I metrics primarily disclosed gender and race/ethnicity percentages among the workforce.

The level of disclosure varied by industry. For example, more than 80% of utilities and insurance companies disclosed D&I information, compared with 38% of those in the banking and capital markets sector. Many companies also shared information about their employee lifecycles, such as how they attract, hire, and retain talent, as well as total rewards, such as the salaries and the benefits they offer.

Although the disclosures varied among companies, the new rule forced them to identify the types of human capital measures and metrics they consider “material” to running their business. That should establish a baseline for future disclosures as companies evolve in how they approach fulfilling this requirement.

Appendix

Talent questions directors can ask management

Overall strategy

- Do we have a workforce plan that forecasts our talent needs now and three to five years in the future?

- Does the plan incorporate changes spurred by COVID-19 that we wish to keep for the medium and long term?

- Do we need to recruit any new kinds of talent, given those changes?

- What’s our strategy for acquiring or developing talent?

- What are the challenges to executing our people strategy?

- Are we adequately investing in skill development, reskilling, upskilling, job redesign, and alternate workforce models to address the workforce implications of COVID-19, as well as rapid technology advancements?

- Does senior leadership recognize the strategic importance of human capital?

- Does our CHRO have the right level of visibility in the boardroom?

Succession planning

- What is our current succession plan, and how far into the organization does it go?

- What is our track record on succession planning (i.e., how often did the company ultimately choose the successor identified in the plan, and how often did it choose another candidate)?

- Are the executives two to three levels below the C-suite getting the experience and training they need to drive strategy—even completely new strategy?

Diversity and inclusion

- How are we investing in recruiting, developing, and promoting a diverse workforce? What are the results of those efforts?

- If we don’t have a diverse workforce, have we conducted a root-cause analysis to determine why? What steps are we taking to address the problem?

- Are we holding executives accountable through compensation metrics or goals?

- Should we consider adopting the “Rooney Rule” of interviewing at least one minority candidate for management positions?

- Are we receiving the data we need to gauge progress on D&I efforts?

Board composition

- Does our board composition reflect the same diversity we expect at the leadership level?

- Does the board have sufficient talent management experience? To what extent have we prioritized this experience when recruiting new directors?

- Are we articulating the full extent of talent management experience on the board in our proxy statement?

Print

Print