Jeffrey Coles is the Samuel S. Stewart, Jr. Presidential Chair in Business, David Eccles Chair, and Professor of Finance; Davidson Heath is an Assistant Professor of Finance; and Matthew Ringgenberg is an Associate Professor of Finance, all at the University of Utah David Eccles School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper, forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics.

Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Scott Hirst; Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance: Theory, Evidence, and Policy (discussed on the forum here) and The Specter of the Giant Three (discussed on the Forum here), both by Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst; and The Limits of Portfolio Primacy (discussed on the Forum here) by Roberto Tallarita.

The last two decades have seen a dramatic increase in the amount of capital invested in passive index funds. While these funds help investors earn benchmark index returns for relatively low fees, the increase in passive investing is not without controversy. Passive investors, by definition, hold portfolios that simply track an index. As a result, they do not do research—they free-ride on the research and analysis of active investors. This leads to a tension: Not everyone can index, some investors must be active for prices to incorporate information. The question is, does the rise of passive investing change information production in the economy? If so, how does passive investing affect informational efficiency, that is, the link between stock prices and fundamental value?

In our paper On Index Investing (Journal of Financial Economics, 2022), we examine these questions, both theoretically and empirically. We first develop a model that is a simple extension of the classic Grossman-Stiglitz (1980) model of information acquisition by investors. We then test the model’s predictions using Russell index reconstitutions as a shock to the mix of passive and active investors. Our findings suggest that passive investing does reduce information production, but perhaps surprisingly, it does not harm informational efficiency.

Existing theories disagree on the relation between investor composition and market efficiency. Some models predict that the rise of passive investing does alter price efficiency. For example, as passive funds replace active funds, there are fewer active funds doing research which could make prices less efficient.

Our extension to the classic Grossman and Stiglitz (1980) model, however, shows this logic is missing an important point. The intuition is simple: investors choose whether to be passive or active. Moreover, they choose to gather private information whenever it is profitable. As a result, our model predicts that an increase in passive investing will reduce information production (because there are fewer active funds), but it will have no effect on price efficiency because the fraction and effort of informed investors will adjust such that the relation between price and fundamental value is unchanged. To put it another way, if the rise of passive investing made prices less efficient, that would give an incentive for some investors to switch back to being active, and they would invest in research until price efficiency was restored.

In the original Grossman and Stiglitz (1980) model, which predates the rise of passive investing, investors choose whether to pay a cost to gather information about a stock. Informed investors pay this cost and then trade on their information, making the price more efficient. We extend the model to include a new option for investors—investors can choose to be passive and buy an index fund. Specifically, in our model investors can choose to be (i) passive, (ii) active but not pay to gather additional private information, or (iii) active and invest in costly information gathering.

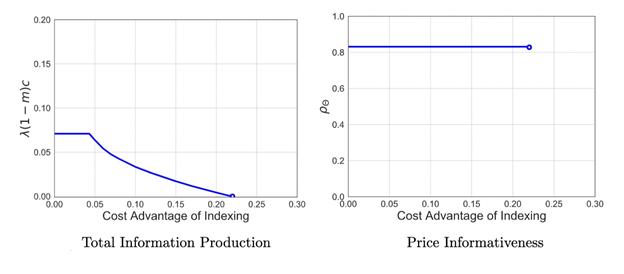

The figure below illustrates the main predictions of our model: as index investing becomes cheaper for investors, more investors choose to index and the number of active investors decreases. Because there are fewer active investors, the total amount of information produced for a given stock falls (left panel), yet the informativeness of the stock price remains unchanged (right panel) because the remaining active investors adjust their behavior to keep price efficiency the same.

We then take our model’s predictions to the data. One of the key challenges to understanding the effects of passive investing is that the quantity of passive capital allocated to a stock is not random. Thus, comparing two stocks with high and low passive ownership is likely to lead to biased estimates. To address this issue, we develop a new research design based on post-2007 Russell Index reconstitutions. Importantly, we show that our analyses do not suffer from the problems that plague many other papers that study Russell Index reconstitutions.

We first show there is a significant shift in the composition of investors after a stock switches between the Russell 1000 and 2000 indexes. For example, when a stock switches from the bottom of the Russell 1000 index to the top of the Russell 2000, we find that ownership by passive funds increases by approximately 2% of its market capitalization, and active ownership falls by a similar amount.

We then examine the effects of such changes in passive investing on information production about the underlying stocks. Using three different measures of information production—Google search volume, EDGAR page views from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and buy-side analyst reports—we find that more passive investing leads to less information production about individual stocks, consistent with our theoretical predictions. Following an exogenous increase in passive ownership, Google search volume about the stock falls by 3.8%, EDGAR page views fall by 14.1%, and the number of analyst reports about the stock falls by 10.8%.

Do these sizable changes in information production affect price efficiency and the informational role of US stock markets? Our answer is “no.” We find that a stock switching indexes is accompanied by zero change in price efficiency. Our estimates are statistically well-powered, meaning that there is a high probability that our tests could find an effect if there were an effect to be found. Still, our tests fail to reject the null of zero changes across a variety of price informativeness measures. Specifically, after an exogenous increase in index investing, we find that information production about individual assets falls but there is no change in the informational efficiency of prices, exactly as our model predicted.

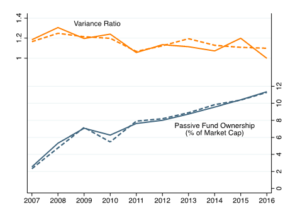

Taken together, our findings are consistent with the idea that index investing changes the composition of investors, which alters market dynamics and information production, but that active investors adjust such that price efficiency is unchanged. Our findings are also echoed by broad trends in equity markets. As the figure below shows, from 2007 to 2016 the fraction of the average U.S. stock owned by passive funds quintupled from 2% to over 11%. This is a truly dramatic shift in how investors invest. Yet at the same time, the average variance ratio across all stocks—a standard measure of price inefficiency—was unchanged. In sum: while related research shows that index funds may adversely impact the governance of public corporations, we present evidence both theoretically and empirically that the rise of index investing is not significantly impacting price efficiency.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print