This post is based on a comment letter submitted to the SEC regarding The proposed rules on Substantial Implementation, Duplication, and Resubmission of Shareholder Proposals by The Shareholder Commons. Below is the text of the letter with minor adjustments to eliminate the correspondence-related parts.

A. Introduction

We submit this letter in response to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (the “Commission”) requests for comment on the Proposed Rules. The Proposed Rules would improve the process by which it is determined whether a proposal made by a shareholder must be included in a company proxy statement and presented for a vote at the company’s annual meeting under Rule 14a-8. The release accompanying the Proposed Rules (the “Release”) also reaffirms the standards that the Commission adopted in 1998 for determining whether a company could exercise the right to exclude a proposal that related to ordinary business (the “1998 Standards” and “Reaffirmation.”)

We strongly support the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation. As noted in the Release, the current rules permitting companies to exclude proposals that (i) have been substantially implemented, (ii) are duplicative of other proposals already submitted for the same meeting, or (iii) that have been submitted in prior years create uncertainty and are not optimally drafted to implement the purpose of Rule 14a-8. We support these proposals for the reasons set forth in the comment submitted to the Commission regarding the Proposed Rules on July 25, 2022, by The Shareholder Rights Group, an association of which TSC is a member.

In this comment, we highlight positive impact that the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation will have on the ability of shareholders to express their views and exercise oversight regarding the social and environmental impact that companies have on the economy and diversified portfolios. This is a critical area where the interests of shareholders and management are more likely to diverge than they are on proposals that are only oriented to the enterprise value of the company itself.

B. Background: portfolio diversification and the two levels of risk for shareholders relating to social and environmental issues: alpha and beta

- Modern investors diversify their portfolios

Modern investing principles emphasize the importance of portfolio diversification. Diversification allows investors to reap the increased returns available from risky securities, but to greatly reduce that risk; this insight defines Modern Portfolio Theory.

This core principle is reflected in federal law, which requires fiduciaries of federally regulated retirement plans to “diversify[] the investments of the plan.” Similar principles govern investment fiduciaries under other legal regimes. The wisdom of a diversified investment strategy was summarized by the late John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, one of the largest mutual funds companies in the world: “Don’t look for the needle in the haystack; instead, buy the haystack.”

- Diversified shareholders are particularly impacted by systemic risk from social and environmental issues

The companies that make up an investor’s portfolio exist in a complex web of social, environmental, and economic systems. The natural environment provides inputs for business like climate, water, and minerals, while social institutions support a healthy and educated workforce, as well as the social stability necessary for long-term investment. Threats to these and other critical systems can pose threats to companies’ financial performance. Conversely, however, company activities can pose threats to these systems.

The interactions between companies and systems creates two distinct types of risks for investors. First, threats to these systems can pose risks to the relative financial performance of individual companies as compared to other companies (“alpha.”) Threats to alpha may arise because a social or environmental system upon which a business model depends is degraded; but threats to alpha may also arise if a company’s business model threatens those systems, because such a company is subject to the risk that its reputation will be tarnished or that its activities will be subject to costly regulation. These risks that systemic concerns pose to the performance of individual companies create risk to a company’s future cash flows and thus its enterprise value; addressing such risks is the province of social and environmental shareholder proposals that are intended to improve company financial performance.

The second type of risk to which investors are exposed is systemic risk—the risk that companies pose to social and environmental systems. These systemic risks threaten the performance of financial markets overall, chiefly by threatening the performance of the global economy (“beta.”)7 As detailed in our comment letter regarding S7-11-22, “Enhanced Disclosure by Certain Investment Advisers and Investment Companies about Environmental, Social and Governance Investment Practices” and S7-16-22, “Investment Company Names,” systemic risk to beta presents a greater threat to long-term, diversified portfolios than do the risks of poor performance by individual companies. As one analysis of the financial industry put it:

Despite all the attention paid to superstar portfolio managers, relative performance has much less impact on wealth creation that the general direction of the market. According to widely held accepted research, alpha is about one-tenth as important as beta.

Of course, a proposal may be intended to improve both enterprise and systemic values. In theory a proposal may also have a purpose unrelated to shareholder financial returns: the proposal process could be used for an ultimate goal of preserving a social or environmental value without considering the financial impact on either the company or shareholders’ portfolios. In our experience, such a pure non- financial purpose is rare, and would be unlikely to garner significant support in light of the fiduciary obligations of many institutional shareholders. In this letter, we confine our comments to the distinction between proposals meant to protect beta and those that focus only on alpha.

C. The Proposed Rules allow for proper distinction between alpha-oriented and beta-oriented proposals.

Proposals designed to improve shareholder returns on similar topics can either be oriented around enterprise value (alpha) concerns and/or systemic (beta) concerns, and the Proposed Rules regarding substantial duplication and resubmission provide a clear basis for recognizing that the two orientations can represent different objectives that would significantly affect implementation. Similarly, under the Proposed Rule regarding substantial implementation, the focus on essential elements provides a clear basis for distinction if the proponents identify the underlying investment goal as either beta or alpha- oriented such that implementation would involve different considerations and modalities.

For example, a proposal might ask that a company increase its minimum pay to provide a living wage as established by a third party. The objective of such a proposal could be to improve either the company’s enterprise value or to improve the health of systems and thus diversified portfolio returns:

- Alpha objective. If the proponent argued that failing to pay a living wage would lead to low employee morale, reduced retention and other business impacts that lowered long-term financial performance at the company, the proposal would appeal to investors who believed that the proposed increase would improve the company’s enterprise value, and any measures to implement the proposal would be guided by that

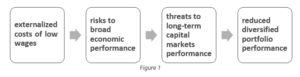

- Beta objective. Alternatively, the proponent might argue that low wages paid by the company and other employers threatened the value of diversified investment portfolios through the costs that low wages externalize; the proponent could further argue that not paying full-time workers enough to provide themselves and their families with stable life circumstances was leading to poor social determinants of health, sub-optimal educational opportunities, severe inequality, and other circumstances that threatened the long-term productivity of the economy and that the threat of lower productivity created risk for the long-term value of its diversified portfolio. This beta risk created by low wages is illustrated in Figure

In this case, two living wage proposals might have very similar characteristics, but very different objectives and thus appeal to different shareholders: as a portfolio’s diversification increases, beta importance relative to alpha increases. Moreover, implementation could be quite different: for an alpha- oriented proposal, direct adoption of a living wage standard would likely be sufficient, and the company would likely emphasize its distinction from other companies that did not adopt a living wage policy in order to appeal to employees, customers and other constituencies that would impact the company’s profitability. In contrast, a company considering a beta-oriented proposal would need to consider how its adoption of such a standard would impact the market more broadly and how it could influence peer companies to pay living wages in order to broadly address the economic costs of low wages. This might involve participation in industry-wide standard setting or political action and a more gradual phase-in that would allow the company to preserve its competitiveness while providing leadership in a movement to address the social cost of low wages.

Many asset owners and managers who file and vote on shareholder proposals are fiduciaries, with obligations to optimize returns to their beneficiaries and clients. The distinction between alpha and beta- oriented proposals is critical to these fiduciaries because a well-intentioned focus on alpha can threaten portfolio value. PRI, an investor initiative whose members have $121 trillion in assets under management, recently described a variety of corporate practices that can boost individual company returns while threatening the economy and diversified investor returns:

A company strengthening its position by externalising costs onto others. The net result for the [diversified] investor can be negative when the costs across the rest of the portfolio (or market/economy) outweigh the gains to the company;

A company or sector securing regulation that favours its interests over others. This can impair broader economic returns when such regulation hinders the development of other, more economic companies or sectors;

A company or sector successfully exploiting common environmental, social or institutional assets. Notwithstanding greater harm to societies, economies, and markets on which investment returns depend, the benefits to the company or sector can be large enough to incentivise and enable them to overpower any defence of common assets.

A recent report from the international law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer explains how the reality of externalized costs reverberates in the fiduciary duties of investment trustees across jurisdictions:

In recent years investors have increasingly focused on what must be done to protect the value of their portfolios from system-wide risks created by the declining sustainability of various aspects of the natural or social environment. System-wide risks are the sort of risks that cannot be mitigated simply by diversifying the investments in a portfolio. They threaten the functioning of the economic, financial, and wider systems on which investment performance relies. If risks of this sort materialised, they would therefore damage the performance of a portfolio as a whole and all portfolios exposed to those systems.

For these fiduciaries, as well as other diversified shareholders seeking to optimize the return of their portfolios, it is critically important that the three exclusions addressed in the Proposed Rules not allow the introduction of alpha-oriented proposals (which may be of limited relevance—or even run counter–to the long-term interests of diversified shareholders) to stifle the ability to bring beta-oriented proposals involving similar subject matter when such orientation would impact implementation. The Proposed Rules provide a clear path for avoiding such an outcome by allowing the proponents of beta-oriented proposals to clarify that such orientation is a distinguishing objective or essential element, respectively. As we discuss in the closing section, additional language could be added to the final rules further buttress this distinction.

D. The Reaffirmation

- Staff Legal Bulletin L and the 2022 proxy season: eliminating the nexus analysis

In reaffirming the 1998 Standards articulated by the Commission with respect to the ordinary business exclusion, the Release confirmed the guidance provided by Staff Legal Bulletin L (“SLB L”).

The release articulating the 1998 Standards explained that a shareholder proposal that might otherwise be excludable as relating to ordinary business under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) is not excludable if it raises significant social policy issues. In explaining ordinary business, the 1998 Release noted:

Certain tasks are so fundamental to management’s ability to run a company on a day-to-day basis that they could not, as a practical matter, be subject to direct shareholder oversight. Examples include the management of the workforce, such as the hiring, promotion, and termination of employees, decisions on production quality and quantity, and the retention of suppliers. However, proposals relating to such matters but focusing on sufficiently significant social policy issues (e.g., significant discrimination matters) generally would not be considered to be excludable, because the proposals would transcend the day-to-day business matters and raise policy issues so significant that it would be appropriate for a shareholder vote.

Further Staff guidance noted that public debate indicated the presence of a significant policy issue:

The Division has noted many times that the presence of widespread public debate regarding an issue is among the factors to be considered in determining whether proposals concerning that issue “transcend the day- to-day business matters.”

The Staff has also indicated that shareholder proposals involve significant social policies if they involve issues that engender widespread debate, media attention, and legislative and regulatory initiatives.

In addition, the Staff had adopted a policy of concurring in the exclusion of proposals that raised a significant policy issue if the proposal did not have significant nexus to the company. However, the Staff recently announced its intention to eliminate the nexus analysis in order to conform to the Commission’s originally articulated standard:

Going forward, the staff will realign its approach for determining whether a proposal relates to “ordinary business” with the standard the Commission initially articulated in 1976, which provided an exception for certain proposals that raise significant social policy issues, and which the Commission subsequently reaffirmed in the 1998 Release. This exception is essential for preserving shareholders’ right to bring important issues before other shareholders by means of the company’s proxy statement, while also recognizing the board’s authority over most day-to-day business matters. For these reasons, staff will no longer focus on determining the nexus between a policy issue and the company, but will instead focus on the social policy significance of the issue that is the subject of the shareholder proposal. In making this determination, the staff will consider whether the proposal raises issues with a broad societal impact, such that they transcend the ordinary business of the company.

Under this realigned approach, proposals that the staff previously viewed as excludable because they did not appear to raise a policy issue of significance for the company may no longer be viewed as excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7). For example, proposals squarely raising human capital management issues with a broad societal impact would not be subject to exclusion solely because the proponent did not demonstrate that the human capital management issue was significant to the company.

In particular, SLB L limited the circumstances in which a proposal that constitutes a significant policy issue could be excluded under Rule 14a-8(i)(5), the “relevance” exception, which generally permits a proposal to be excluded if it relates to less than 5 percent of a company’s business and “is not otherwise significantly related to the company’s business.” Specifically, SLB L stated that:

proposals that raise issues of broad social or ethical concern related to the company’s business may not be excluded, even if the relevant business falls below the economic thresholds of Rule 14a-8(i)(5).

In reaching this conclusion, the Staff cited Lovenheim v. Iroquois Brands, Ltd. Lovenheim involved a motion for a preliminary injunction, and the court found that a proposal seeking a study on the company’s sale of pâté de foie gras and animal cruelty was not likely to be found to be excludable under Rule 14a- 8(i)(5) because of its social significance, even though sales of the product represented only $79,000 of the company’s $141 million in revenue and $34,000 of a total of $78 million in assets, or 0.06% and 0.04% of revenue and assets, respectively.

Read together, the 1998 Standards, Lovenheim, and SLB L demonstrate that issues of broad societal impact may not be excluded, as long as they bear a de minimis relation to firm operations, even if orders of magnitude below the economic threshold established under the relevance exception.

This outcome was confirmed by the Staff’s decision not to grant no-action relief in the 2022 proxy season regarding the following proposal presented to CVS Health Corporation:

RESOLVED, shareholders ask that the board commission and publish a report on (1) the link between the public-health costs created by the Company’s food, beverage, and candy business and its prioritization of financial returns over its healthcare purpose and (2) whether such prioritization threatens the returns of diversified shareholders who rely on a productive economy to support their investment portfolios.

In the 2021 proxy season, the Staff had issued no-action relief under the ordinary business exclusion for a similar proposal, clarifying in response to a request for reconsideration that it had granted relief in reliance upon the nexus rule.

However, the request for relief in the 2022 proxy season followed the issuance of SLB L, which lead to a different result. CVS Health asserted that the 2022 Proposal was excludable because it was not economically or otherwise significant to CVS Health (Rule 14a-8(i)(5)) and because it related to ordinary business (Rule 14a-8(i)(7)).

The proponent argued that the proposal was not excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) because it was directed to a significant policy issue posed by the Company’s ongoing business, namely the question of how a corporation accounts for the costs it imposes on stakeholders when it prioritizes the interests of its shareholders, in this instance by increasing the public health costs associated with the sale of unhealthful food to consumers seeking health products and services. In addition, the proponent argued, CVS Health’s decision to promote and sell unhealthful products to improve its financial return implicates a second significant policy issue: the growing obesity epidemic and its relationship to poor diet, including excessive sugar intake. The staff declined to issue relief, affirming that the amount of business involved would not be a factor if the proposal related to a policy issue with broad societal impact.

For two other 2022 proposals, however, the Staff granted relief under the ordinary business exclusion where it had previously granted relief expressly under the nexus requirement. Those proposals requested that companies provide a report to shareholders as to how underwriting initial public offerings with dual class capital structures could harm the economy and, consequently, diversified shareholders dependent upon beta for long term value creation.

The proponents had responded to the Companies’ requests by demonstrating that dual class capital structures had engendered widespread debate, media attention, and legislative and regulatory initiatives, and have broad societal impact. Nevertheless, the Staff concurred that the proposals did not transcend ordinary business

2. The beneficial impact of eliminating the nexus analysis on beta-oriented proposals

As discussed in Sections B and C, the beta impact that a company has on social and environmental systems is generally more important to a diversified shareholder than the impact of such systems on the company itself. One recent work explained that these systematic beta risks inevitably “swamp” any benefits to be gained by pursuing an alpha investing strategy:

It is not that alpha does not matter to an investor (although investors only want positive alpha, which is impossible on a total market basis), but that the impact of the market return driven by systematic risk swamps virtually any possible scenario created by skillful analysis or trading or portfolio construction.

Thus, from the perspective of diversified shareholders, the nexus test frustrated their ability to bring matters of greatest significance to the company and fellow shareholders. Returning to the example of CVS, even if sales of unhealthy food were only a small part of the company’s business and thus not material to its financial performance, the sale of that food to a large segment of the U.S. population that was receiving treatment for disease related to diet could have a significant negative impact on the U.S. economy, and thus on shareholders of CVS with diversified portfolios. Elimination of the nexus analysis removed a significant barrier to beta-oriented engagement.

However, the Staff concurrence in the exclusion of proposals in Goldman 2022 and JPMorgan 2022 suggests that the final rules or accompanying release should further clarify that the test of “broad societal impact” should be deemed to be satisfied if the impact is one that is likely to affect a company’s diversified shareholders by impacting the performance of capital markets. In other words, if a proposal is directed towards a company practice that has an impact on society that could reduce economic productivity and consequently lower overall market returns, the issue should be treated as one that transcends ordinary business and is thus not excludable. This interpretation supports the purpose of Rule 14a-8, which is to give the owners of the company a voice in how the company is run with respect to matters important to their interests.

E. Beta proposals address the conflict at the heart of our financial system

The shareholder proposal process is critically important where the interests of shareholders and company executives are not aligned; situations where companies can boost alpha with practices that threaten beta are the quintessential examples of such misalignment.

The reality of modern economic life is that companies are able to boost their own enterprise value by externalizing costs. A recent study determined that in 2018, publicly listed companies around the world imposed social and environmental costs on the economy with a value of $2.2 trillion annually—more than 2.5 percent of global GDP. This cost was more than half of the profits those companies reported.

But as Figures 1 illustrates, that boost to alpha may come at a cost to beta, which is more important to the returns of most shareholders than is alpha at any single company; as Lukomnik and Hawley put it, alpha “swamps” beta. This effect creates a conflict of interest for company executives. Their success is not measured by the performance of capital markets overall, but by the performance of their company. The only impact of their decisions that creates a strong financial signal is the effect on the company’s own cash flows, enterprise value and share price. This conflict is reified by compensation packages that provide executives (and sometimes directors) with large, concentrated interests in the equity of their companies.

All of this means that corporate managers have an intrinsic motivation to focus on making decisions that improve company returns, even if those decisions come at a cost to beta, and thus their own diversified investors. Returning to the example of the living wage question, corporate managers are incentivized to resist paying a living that threatens company alpha, even if supporting such a wage would improve beta and the company’s shareholders would benefit from the prioritization of beta over alpha. These managers have an interest in promoting alpha-oriented social and environmental programs, but not beta-oriented initiatives, even though it is beta that is most important to most modern investors.

By creating regulatory infrastructure that more clearly supports beta-oriented proposals, the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation improve the ability of shareholders to use the proposal process to address this conflict through oversight and communication with fellow shareholders. The next section suggests additional measures to strengthen this support.

F. Proposed revisions

- Clarify that a beta purpose distinguishes a proposal

In order to clarify that a purpose of improving beta through systems stewardship can distinguish a proposal from a similar one that is only intended to improve the financial performance of the company, we propose adding the following note immediately following paragraph (12):

NOTE TO PARAGRAPHS (I)(10)-(12): When a proposal has an express purpose of improving the effect that a company has on diversified portfolio values through its social or environmental impacts, we will treat such purpose as an essential element and objective of a proposal that would distinguish it from proposals that do not have such a purpose under paragraphs (i)(10)-(12) if such purpose could significantly affect the means of implementation of the proposal.

As an alternative, the release accompanying the final rules could clarify this point.

2. Clarify that a policy issue will be treated as having broad societal impact if it the issue has an effect on beta

In order to clarify that policy issues that impact the returns of diversified shareholders transcend ordinary business and are thus not excludable, we propose that the release accompanying the final rules include a statement to the following effect:

If a proposal is directed towards a company practice that has an impact on society that could reduce economic productivity and consequently lower overall market returns, the issue should be treated as one that transcends ordinary business and is thus not excludable.

* * * *

For all the reasons expressed above, we urge that the Proposed Rules be adopted and that final rules and accompanying release include modifications that (1) provide greater specificity regarding the distinct nature of beta-oriented proposals and (2) clarify that proposals addressing policy issues likely to impact overall market performance transcend ordinary business. Such adoption and modifications will ensure that the shareholder proposal process enables shareholder to bring proposals most relevant to their success as investors and to use the proposal process where company executives are most likely to have misaligned incentives.

The complete comment letter is available for download here.

Proposed rules on Shareholder Proposals: A Comment From The Shareholder Commons

More from: Alexander Frederick, The Shareholder Commons

Frederick Alexander is Founder of The Shareholder Commons. This post is based on a recent comment letter submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission regarding the proposed rules on substantial implementation, duplication, and resubmission of shareholder proposals by The Shareholder Commons.

This post is based on a comment letter submitted to the SEC regarding The proposed rules on Substantial Implementation, Duplication, and Resubmission of Shareholder Proposals by The Shareholder Commons. Below is the text of the letter with minor adjustments to eliminate the correspondence-related parts.

A. Introduction

We submit this letter in response to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (the “Commission”) requests for comment on the Proposed Rules. The Proposed Rules would improve the process by which it is determined whether a proposal made by a shareholder must be included in a company proxy statement and presented for a vote at the company’s annual meeting under Rule 14a-8. The release accompanying the Proposed Rules (the “Release”) also reaffirms the standards that the Commission adopted in 1998 for determining whether a company could exercise the right to exclude a proposal that related to ordinary business (the “1998 Standards” and “Reaffirmation.”)

We strongly support the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation. As noted in the Release, the current rules permitting companies to exclude proposals that (i) have been substantially implemented, (ii) are duplicative of other proposals already submitted for the same meeting, or (iii) that have been submitted in prior years create uncertainty and are not optimally drafted to implement the purpose of Rule 14a-8. We support these proposals for the reasons set forth in the comment submitted to the Commission regarding the Proposed Rules on July 25, 2022, by The Shareholder Rights Group, an association of which TSC is a member.

In this comment, we highlight positive impact that the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation will have on the ability of shareholders to express their views and exercise oversight regarding the social and environmental impact that companies have on the economy and diversified portfolios. This is a critical area where the interests of shareholders and management are more likely to diverge than they are on proposals that are only oriented to the enterprise value of the company itself.

B. Background: portfolio diversification and the two levels of risk for shareholders relating to social and environmental issues: alpha and beta

Modern investing principles emphasize the importance of portfolio diversification. Diversification allows investors to reap the increased returns available from risky securities, but to greatly reduce that risk; this insight defines Modern Portfolio Theory.

This core principle is reflected in federal law, which requires fiduciaries of federally regulated retirement plans to “diversify[] the investments of the plan.” Similar principles govern investment fiduciaries under other legal regimes. The wisdom of a diversified investment strategy was summarized by the late John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, one of the largest mutual funds companies in the world: “Don’t look for the needle in the haystack; instead, buy the haystack.”

The companies that make up an investor’s portfolio exist in a complex web of social, environmental, and economic systems. The natural environment provides inputs for business like climate, water, and minerals, while social institutions support a healthy and educated workforce, as well as the social stability necessary for long-term investment. Threats to these and other critical systems can pose threats to companies’ financial performance. Conversely, however, company activities can pose threats to these systems.

The interactions between companies and systems creates two distinct types of risks for investors. First, threats to these systems can pose risks to the relative financial performance of individual companies as compared to other companies (“alpha.”) Threats to alpha may arise because a social or environmental system upon which a business model depends is degraded; but threats to alpha may also arise if a company’s business model threatens those systems, because such a company is subject to the risk that its reputation will be tarnished or that its activities will be subject to costly regulation. These risks that systemic concerns pose to the performance of individual companies create risk to a company’s future cash flows and thus its enterprise value; addressing such risks is the province of social and environmental shareholder proposals that are intended to improve company financial performance.

The second type of risk to which investors are exposed is systemic risk—the risk that companies pose to social and environmental systems. These systemic risks threaten the performance of financial markets overall, chiefly by threatening the performance of the global economy (“beta.”)7 As detailed in our comment letter regarding S7-11-22, “Enhanced Disclosure by Certain Investment Advisers and Investment Companies about Environmental, Social and Governance Investment Practices” and S7-16-22, “Investment Company Names,” systemic risk to beta presents a greater threat to long-term, diversified portfolios than do the risks of poor performance by individual companies. As one analysis of the financial industry put it:

Despite all the attention paid to superstar portfolio managers, relative performance has much less impact on wealth creation that the general direction of the market. According to widely held accepted research, alpha is about one-tenth as important as beta.

Of course, a proposal may be intended to improve both enterprise and systemic values. In theory a proposal may also have a purpose unrelated to shareholder financial returns: the proposal process could be used for an ultimate goal of preserving a social or environmental value without considering the financial impact on either the company or shareholders’ portfolios. In our experience, such a pure non- financial purpose is rare, and would be unlikely to garner significant support in light of the fiduciary obligations of many institutional shareholders. In this letter, we confine our comments to the distinction between proposals meant to protect beta and those that focus only on alpha.

C. The Proposed Rules allow for proper distinction between alpha-oriented and beta-oriented proposals.

Proposals designed to improve shareholder returns on similar topics can either be oriented around enterprise value (alpha) concerns and/or systemic (beta) concerns, and the Proposed Rules regarding substantial duplication and resubmission provide a clear basis for recognizing that the two orientations can represent different objectives that would significantly affect implementation. Similarly, under the Proposed Rule regarding substantial implementation, the focus on essential elements provides a clear basis for distinction if the proponents identify the underlying investment goal as either beta or alpha- oriented such that implementation would involve different considerations and modalities.

For example, a proposal might ask that a company increase its minimum pay to provide a living wage as established by a third party. The objective of such a proposal could be to improve either the company’s enterprise value or to improve the health of systems and thus diversified portfolio returns:

In this case, two living wage proposals might have very similar characteristics, but very different objectives and thus appeal to different shareholders: as a portfolio’s diversification increases, beta importance relative to alpha increases. Moreover, implementation could be quite different: for an alpha- oriented proposal, direct adoption of a living wage standard would likely be sufficient, and the company would likely emphasize its distinction from other companies that did not adopt a living wage policy in order to appeal to employees, customers and other constituencies that would impact the company’s profitability. In contrast, a company considering a beta-oriented proposal would need to consider how its adoption of such a standard would impact the market more broadly and how it could influence peer companies to pay living wages in order to broadly address the economic costs of low wages. This might involve participation in industry-wide standard setting or political action and a more gradual phase-in that would allow the company to preserve its competitiveness while providing leadership in a movement to address the social cost of low wages.

Many asset owners and managers who file and vote on shareholder proposals are fiduciaries, with obligations to optimize returns to their beneficiaries and clients. The distinction between alpha and beta- oriented proposals is critical to these fiduciaries because a well-intentioned focus on alpha can threaten portfolio value. PRI, an investor initiative whose members have $121 trillion in assets under management, recently described a variety of corporate practices that can boost individual company returns while threatening the economy and diversified investor returns:

A company strengthening its position by externalising costs onto others. The net result for the [diversified] investor can be negative when the costs across the rest of the portfolio (or market/economy) outweigh the gains to the company;

A company or sector securing regulation that favours its interests over others. This can impair broader economic returns when such regulation hinders the development of other, more economic companies or sectors;

A company or sector successfully exploiting common environmental, social or institutional assets. Notwithstanding greater harm to societies, economies, and markets on which investment returns depend, the benefits to the company or sector can be large enough to incentivise and enable them to overpower any defence of common assets.

A recent report from the international law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer explains how the reality of externalized costs reverberates in the fiduciary duties of investment trustees across jurisdictions:

In recent years investors have increasingly focused on what must be done to protect the value of their portfolios from system-wide risks created by the declining sustainability of various aspects of the natural or social environment. System-wide risks are the sort of risks that cannot be mitigated simply by diversifying the investments in a portfolio. They threaten the functioning of the economic, financial, and wider systems on which investment performance relies. If risks of this sort materialised, they would therefore damage the performance of a portfolio as a whole and all portfolios exposed to those systems.

For these fiduciaries, as well as other diversified shareholders seeking to optimize the return of their portfolios, it is critically important that the three exclusions addressed in the Proposed Rules not allow the introduction of alpha-oriented proposals (which may be of limited relevance—or even run counter–to the long-term interests of diversified shareholders) to stifle the ability to bring beta-oriented proposals involving similar subject matter when such orientation would impact implementation. The Proposed Rules provide a clear path for avoiding such an outcome by allowing the proponents of beta-oriented proposals to clarify that such orientation is a distinguishing objective or essential element, respectively. As we discuss in the closing section, additional language could be added to the final rules further buttress this distinction.

D. The Reaffirmation

In reaffirming the 1998 Standards articulated by the Commission with respect to the ordinary business exclusion, the Release confirmed the guidance provided by Staff Legal Bulletin L (“SLB L”).

The release articulating the 1998 Standards explained that a shareholder proposal that might otherwise be excludable as relating to ordinary business under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) is not excludable if it raises significant social policy issues. In explaining ordinary business, the 1998 Release noted:

Certain tasks are so fundamental to management’s ability to run a company on a day-to-day basis that they could not, as a practical matter, be subject to direct shareholder oversight. Examples include the management of the workforce, such as the hiring, promotion, and termination of employees, decisions on production quality and quantity, and the retention of suppliers. However, proposals relating to such matters but focusing on sufficiently significant social policy issues (e.g., significant discrimination matters) generally would not be considered to be excludable, because the proposals would transcend the day-to-day business matters and raise policy issues so significant that it would be appropriate for a shareholder vote.

Further Staff guidance noted that public debate indicated the presence of a significant policy issue:

The Division has noted many times that the presence of widespread public debate regarding an issue is among the factors to be considered in determining whether proposals concerning that issue “transcend the day- to-day business matters.”

The Staff has also indicated that shareholder proposals involve significant social policies if they involve issues that engender widespread debate, media attention, and legislative and regulatory initiatives.

In addition, the Staff had adopted a policy of concurring in the exclusion of proposals that raised a significant policy issue if the proposal did not have significant nexus to the company. However, the Staff recently announced its intention to eliminate the nexus analysis in order to conform to the Commission’s originally articulated standard:

Going forward, the staff will realign its approach for determining whether a proposal relates to “ordinary business” with the standard the Commission initially articulated in 1976, which provided an exception for certain proposals that raise significant social policy issues, and which the Commission subsequently reaffirmed in the 1998 Release. This exception is essential for preserving shareholders’ right to bring important issues before other shareholders by means of the company’s proxy statement, while also recognizing the board’s authority over most day-to-day business matters. For these reasons, staff will no longer focus on determining the nexus between a policy issue and the company, but will instead focus on the social policy significance of the issue that is the subject of the shareholder proposal. In making this determination, the staff will consider whether the proposal raises issues with a broad societal impact, such that they transcend the ordinary business of the company.

Under this realigned approach, proposals that the staff previously viewed as excludable because they did not appear to raise a policy issue of significance for the company may no longer be viewed as excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7). For example, proposals squarely raising human capital management issues with a broad societal impact would not be subject to exclusion solely because the proponent did not demonstrate that the human capital management issue was significant to the company.

In particular, SLB L limited the circumstances in which a proposal that constitutes a significant policy issue could be excluded under Rule 14a-8(i)(5), the “relevance” exception, which generally permits a proposal to be excluded if it relates to less than 5 percent of a company’s business and “is not otherwise significantly related to the company’s business.” Specifically, SLB L stated that:

proposals that raise issues of broad social or ethical concern related to the company’s business may not be excluded, even if the relevant business falls below the economic thresholds of Rule 14a-8(i)(5).

In reaching this conclusion, the Staff cited Lovenheim v. Iroquois Brands, Ltd. Lovenheim involved a motion for a preliminary injunction, and the court found that a proposal seeking a study on the company’s sale of pâté de foie gras and animal cruelty was not likely to be found to be excludable under Rule 14a- 8(i)(5) because of its social significance, even though sales of the product represented only $79,000 of the company’s $141 million in revenue and $34,000 of a total of $78 million in assets, or 0.06% and 0.04% of revenue and assets, respectively.

Read together, the 1998 Standards, Lovenheim, and SLB L demonstrate that issues of broad societal impact may not be excluded, as long as they bear a de minimis relation to firm operations, even if orders of magnitude below the economic threshold established under the relevance exception.

This outcome was confirmed by the Staff’s decision not to grant no-action relief in the 2022 proxy season regarding the following proposal presented to CVS Health Corporation:

RESOLVED, shareholders ask that the board commission and publish a report on (1) the link between the public-health costs created by the Company’s food, beverage, and candy business and its prioritization of financial returns over its healthcare purpose and (2) whether such prioritization threatens the returns of diversified shareholders who rely on a productive economy to support their investment portfolios.

In the 2021 proxy season, the Staff had issued no-action relief under the ordinary business exclusion for a similar proposal, clarifying in response to a request for reconsideration that it had granted relief in reliance upon the nexus rule.

However, the request for relief in the 2022 proxy season followed the issuance of SLB L, which lead to a different result. CVS Health asserted that the 2022 Proposal was excludable because it was not economically or otherwise significant to CVS Health (Rule 14a-8(i)(5)) and because it related to ordinary business (Rule 14a-8(i)(7)).

The proponent argued that the proposal was not excludable under Rule 14a-8(i)(7) because it was directed to a significant policy issue posed by the Company’s ongoing business, namely the question of how a corporation accounts for the costs it imposes on stakeholders when it prioritizes the interests of its shareholders, in this instance by increasing the public health costs associated with the sale of unhealthful food to consumers seeking health products and services. In addition, the proponent argued, CVS Health’s decision to promote and sell unhealthful products to improve its financial return implicates a second significant policy issue: the growing obesity epidemic and its relationship to poor diet, including excessive sugar intake. The staff declined to issue relief, affirming that the amount of business involved would not be a factor if the proposal related to a policy issue with broad societal impact.

For two other 2022 proposals, however, the Staff granted relief under the ordinary business exclusion where it had previously granted relief expressly under the nexus requirement. Those proposals requested that companies provide a report to shareholders as to how underwriting initial public offerings with dual class capital structures could harm the economy and, consequently, diversified shareholders dependent upon beta for long term value creation.

The proponents had responded to the Companies’ requests by demonstrating that dual class capital structures had engendered widespread debate, media attention, and legislative and regulatory initiatives, and have broad societal impact. Nevertheless, the Staff concurred that the proposals did not transcend ordinary business

2. The beneficial impact of eliminating the nexus analysis on beta-oriented proposals

As discussed in Sections B and C, the beta impact that a company has on social and environmental systems is generally more important to a diversified shareholder than the impact of such systems on the company itself. One recent work explained that these systematic beta risks inevitably “swamp” any benefits to be gained by pursuing an alpha investing strategy:

It is not that alpha does not matter to an investor (although investors only want positive alpha, which is impossible on a total market basis), but that the impact of the market return driven by systematic risk swamps virtually any possible scenario created by skillful analysis or trading or portfolio construction.

Thus, from the perspective of diversified shareholders, the nexus test frustrated their ability to bring matters of greatest significance to the company and fellow shareholders. Returning to the example of CVS, even if sales of unhealthy food were only a small part of the company’s business and thus not material to its financial performance, the sale of that food to a large segment of the U.S. population that was receiving treatment for disease related to diet could have a significant negative impact on the U.S. economy, and thus on shareholders of CVS with diversified portfolios. Elimination of the nexus analysis removed a significant barrier to beta-oriented engagement.

However, the Staff concurrence in the exclusion of proposals in Goldman 2022 and JPMorgan 2022 suggests that the final rules or accompanying release should further clarify that the test of “broad societal impact” should be deemed to be satisfied if the impact is one that is likely to affect a company’s diversified shareholders by impacting the performance of capital markets. In other words, if a proposal is directed towards a company practice that has an impact on society that could reduce economic productivity and consequently lower overall market returns, the issue should be treated as one that transcends ordinary business and is thus not excludable. This interpretation supports the purpose of Rule 14a-8, which is to give the owners of the company a voice in how the company is run with respect to matters important to their interests.

E. Beta proposals address the conflict at the heart of our financial system

The shareholder proposal process is critically important where the interests of shareholders and company executives are not aligned; situations where companies can boost alpha with practices that threaten beta are the quintessential examples of such misalignment.

The reality of modern economic life is that companies are able to boost their own enterprise value by externalizing costs. A recent study determined that in 2018, publicly listed companies around the world imposed social and environmental costs on the economy with a value of $2.2 trillion annually—more than 2.5 percent of global GDP. This cost was more than half of the profits those companies reported.

But as Figures 1 illustrates, that boost to alpha may come at a cost to beta, which is more important to the returns of most shareholders than is alpha at any single company; as Lukomnik and Hawley put it, alpha “swamps” beta. This effect creates a conflict of interest for company executives. Their success is not measured by the performance of capital markets overall, but by the performance of their company. The only impact of their decisions that creates a strong financial signal is the effect on the company’s own cash flows, enterprise value and share price. This conflict is reified by compensation packages that provide executives (and sometimes directors) with large, concentrated interests in the equity of their companies.

All of this means that corporate managers have an intrinsic motivation to focus on making decisions that improve company returns, even if those decisions come at a cost to beta, and thus their own diversified investors. Returning to the example of the living wage question, corporate managers are incentivized to resist paying a living that threatens company alpha, even if supporting such a wage would improve beta and the company’s shareholders would benefit from the prioritization of beta over alpha. These managers have an interest in promoting alpha-oriented social and environmental programs, but not beta-oriented initiatives, even though it is beta that is most important to most modern investors.

By creating regulatory infrastructure that more clearly supports beta-oriented proposals, the Proposed Rules and Reaffirmation improve the ability of shareholders to use the proposal process to address this conflict through oversight and communication with fellow shareholders. The next section suggests additional measures to strengthen this support.

F. Proposed revisions

In order to clarify that a purpose of improving beta through systems stewardship can distinguish a proposal from a similar one that is only intended to improve the financial performance of the company, we propose adding the following note immediately following paragraph (12):

NOTE TO PARAGRAPHS (I)(10)-(12): When a proposal has an express purpose of improving the effect that a company has on diversified portfolio values through its social or environmental impacts, we will treat such purpose as an essential element and objective of a proposal that would distinguish it from proposals that do not have such a purpose under paragraphs (i)(10)-(12) if such purpose could significantly affect the means of implementation of the proposal.

As an alternative, the release accompanying the final rules could clarify this point.

2. Clarify that a policy issue will be treated as having broad societal impact if it the issue has an effect on beta

In order to clarify that policy issues that impact the returns of diversified shareholders transcend ordinary business and are thus not excludable, we propose that the release accompanying the final rules include a statement to the following effect:

If a proposal is directed towards a company practice that has an impact on society that could reduce economic productivity and consequently lower overall market returns, the issue should be treated as one that transcends ordinary business and is thus not excludable.

* * * *

For all the reasons expressed above, we urge that the Proposed Rules be adopted and that final rules and accompanying release include modifications that (1) provide greater specificity regarding the distinct nature of beta-oriented proposals and (2) clarify that proposals addressing policy issues likely to impact overall market performance transcend ordinary business. Such adoption and modifications will ensure that the shareholder proposal process enables shareholder to bring proposals most relevant to their success as investors and to use the proposal process where company executives are most likely to have misaligned incentives.

The complete comment letter is available for download here.