Susan H. Mac Cormac is a Partner and Michael P. Santos is an Associate at Morrison Foerster LLP, and Divya Walia is a Research Fellow at Impact Capital Managers. This post is based on a Morrison Foerster and Impact Capital Managers memorandum by Ms. Mac Cormac, Mr. Santos, Ms. Walia, Harry M. Stanwick, Daniel J. Irvin, and Marieka Spence. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; How Much Do Investors Care about Social Responsibility? (discussed on the Forum here) by Scott Hirst, Kobi Kastiel, and Tamar Kricheli-Katz; Does Enlightened Shareholder Value add Value (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, Roberto Tallarita; and Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee (discussed on the Forum here) by Max M. Schanzenbach and Robert H. Sitkoff.

Introduction

Executive Summary

Impact Capital Managers represents over $60 billion of impact-focused capital and connects a network of 100+ of the leading private capital investment funds seeking competitive, market rate returns. As market-rate investors, the challenge for ICM member organizations is to prove that impact can and does drive financial return. Inconsistency in impact measurement and reporting makes it difficult to establish a quantitative correlation between impact and financial performance. However, ICM member examples demonstrate that, when done right, effective investment stewardship from an impact perspective is the same as effective stewardship from a financial perspective. Nowhere is this clearer than at the exit stage, where impact and financial value creation during the life of the investment are realized. This report is interested in showing the impact-specific drivers that most influenced exit outcomes for ICM portfolio companies. While this report centers on ICM members’ firms, we hope the findings can be useful for the private capital impact investing landscape more broadly.

ICM member organizations represent just one pillar of the effort to mobilize capital towards crucial social and environmental issues. As market-rate investors, ICM funds should be assessed independently from other investors on the impact capital spectrum, including concessionary rate investment funds, philanthropy, and public organizations. ICM members also differ from other areas of the sustainable investing landscape in that they represent mainly private capital. On one hand, this gives investors freedom from short term shareholder pressure and allows for a focus on long-term impact creation. However, this also creates opacity around their impact and its relationship to realized financial value.

This report attempts to reduce some of that opacity by including transaction-level information that show both impact and financial return. This report is also focused on specific considerations that impact investors face at exit. Unlike traditional investors, realized financial value is not the only outcome that matters. As mission-driven capital allocators, most ICM firms are interested in impact created and future impact potential as metrics of exit success. Impact investors are also concerned with how to protect that impact at exit. Many general partners have committed to their limited partners in their governing documents that they will seek to create impact with their investments. Protecting impact at exit and fulfilling their commitments to their limited partners is thus of particular importance. In addition to exit-level analysis, the report includes a discussion of impact tools used by investors to create and maintain impact at exit.

Background

Over the course of the past decade, evidence that impact investing can be an effective investing thesis has continued to mount. Alongside academic studies and benchmarks showing that impact investments can perform just as well as conventional investments, proof that impact investments can promote positive social and environmental outcomes is growing.

Research efforts over the past 8 – 10 years include both quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative research on the financial performance of impact investments is typically pooled at the fund level, while quantitative research on impact performance generally aims to quantify the social and environmental impact of impact investments. Qualitative research and case studies on the business value of applying an impact lens throughout the investment lifecycle is also a major component of outstanding research.

In aggregate, these studies represent a growing body of evidence for the potential of impact investing to drive financial returns and positive social and environmental outcomes. While they have not yet proven that impact investments consistently outperform, they have demonstrated that some do. In comparison to traditional investments, impact investments trend towards factors that mitigate risk during volatile market conditions, such as having a resilient workforce and being consistently attractive to investors. Research has also uncovered the mechanisms by which using an impact lens (e.g., seeking businesses with positive impact and managing toward those goals) can help manage a portfolio and add value for companies.

However, fund managers continue to face an uphill battle in convincing many investors that impact can be achieved alongside competitive financial returns. The misperception that impact means sacrificing returns hinders the growth of the field, particularly in the private equity and venture capital space, where the opportunity to catalyze impact is arguably the greatest. At this pivotal moment for the field, analyzing the track record of portfolio company exits by impact investors may help corroborate the link between impact and realized financial value.

Research Objective

In 2018, Impact Capital Managers (ICM) and Tideline published The Alpha in Impact, which outlined the ways in which impact objectives enhance financial performance, drawing from evidence within ICM member funds. The report categorized the concept of “impact alpha” into ten specific drivers within three core areas: accessing opportunities, creating value, and strengthening outcomes (see page 3).

Since the publication of the last Alpha in Impact report, the impact investing field has achieved substantial growth. In 2018, The Global Impact Investment Network’s (GIIN) Annual Impact Investor Survey included 226 respondents, estimating a total market size of $228 billion in assets under management (AUM). As of October 2022, the GIIN reported an estimated market size of $1.164 trillion, with over 3,349 impact investing organizations. This reflects a ~50% annual growth rate for impact AUM during this period. This unprecedented growth in the industry is reflected in ICM’s membership, which has grown from 35 members to over 100 since the last report.

This next research venture aims to address the new questions arising from this growing field and continues ICM’s mission to empower impact funds in creating long-lasting value for their investors and the communities and causes they support. An increased and up-to-date sample size of realized exits can help draw firmer conclusions about the relationship between impact and alpha at exit and provides rich material for analysis of our ten identified value drivers. With now over 100 member funds representing $60 billion in impact-focused, market rate return capital, ICM is uniquely positioned to examine this data set. Preliminary research has shown that successful exits have been occurring in impact investing, mainly via strategic acquisition and secondary sale, with a few IPOs. Our research objectives were as follows:

- Analyze the ways in which selecting and managing for positive impact drives realized value at exit.

- Identify variables that affect the ways impact drives exit.

- Surface examples that illustrate how this value is captured at exit.

Research Approach

Our research approach had two goals. First, we aimed to make use of ICM’s large membership base to draw conclusions on the overall landscape of portfolio company exits by impact investors. Next, we wanted to closely analyze specific examples of exits to identify a comprehensive set of potential driving variables for both successful and unsuccessful exits.

The first part of our research began in March 2022. We disseminated a survey to the full ICM membership (at that time consisting of 78 member firms) asking them to list all of their completed exits. We received full or partial responses from 30 firms, which yielded information for ~230 exits. Our goal at this stage was to get a broad understanding of the types of portfolio company exits impact investors were making, in which industries, and generally gauge the perceived performance of those exits and what drove that performance.

A persistent challenge faced by researchers in this field is the developing but inconsistent approaches to impact measurement and reporting in the broad impact investing industry, which is also the case in assessing ICM member firms. The lack of consistent approaches to impact measurement limited our ability to objectively compare results across firms. While industry-wide initiatives have made strides in this area, this issue remains a barrier to understanding true quantitative correlation between impact and financial value. As an organization, ICM encourages process-oriented standards around impact measurement. This framework is intentionally not prescriptive to acknowledge that each fund’s unique sector, stage, and size necessitate different forms of measurement. Despite this inherent subjectivity, we still believed that comparing firms’ performance against expectations was valuable to understand the relationship between financial and impact performance for each exit.

Accordingly, we designed our survey questions on financial and impact performance knowing they would be subjective, but with the goal to maintain consistency. Each firm had a base-level expectation for financial and impact performance, regardless of how performance was measured. For example, expected financial performance is often indicated through a hurdle rate, a target IRR, or MOIC level. While the “expected impact level” is more complicated, ICM firms are expected to have clear impact objectives and follow some sort of measurement and data collection process to assess alignment with the stated objective. We asked firms to state the outcome of the exit relative to their target level: did the exit outperform, perform at target, or underperform relative to expectations? This question was asked for both financial and impact “return.” We also asked firms to link the outcome of the exit to the ten Impact Drivers from the original Alpha in Impact report to better understand the most important determinants of exit outcome from an impact lens.

The second phase of our research dived deeper into specific exits to disaggregate and evaluate the drivers of realized value at exit. While all ICM members were invited to participate at the time of data collection, firms decided whether to opt-in to the study. We acknowledge that self-reporting could cause bias towards “winning” exits for firms. However, the linkages we draw between impact considerations in the investment process and exit outcomes are the result of strategies deployed by fund managers across extensive portfolios, including lessons learned from underperformers. During numerous interviews, ICM members discussed lessons learned from prior impact investments, both successful and unsuccessful.

The exit-specific deep dives involved a second, more comprehensive survey and an in-depth interview. At this stage, we organized our data collection around three primary questions:

- How does selecting impact targets drive realized value?

- How does investing for impact help attract buyers?

- How do impact-driven tools help increase impact value at exit?

Key Themes

In addition to general observations from a broad data set, our data collection revealed a set of key themes that emerged around each of our focus questions. These themes tie impact-specific drivers to realized value at exit.

How does selecting impact targets drive realized value?

- Targeted Capital Provider for Impact: Impact investors are seen as uniquely additive to firms who are looking to raise capital from mission-aligned investors. As compared to traditional funds, impact funds are branded as better long-term partners with more patience around the exit process, especially for small- and medium-sized businesses. Many ICM funds are thematic investors focused on one impact theme or sector. Thematic impact investors who have gained name recognition due to their track record are often sought out for their industry-specific expertise. Being an impact-driven capital provider can thus expand the opportunity set for investment and create strong alignment with management early on.

- Specific Impact Framework: Some impact firms deploy specific frameworks to guide portfolio companies to their targeted impact objectives. Such frameworks include concrete steps towards creating quality jobs, increasing employee engagement, or improving sustainability practices. Through careful deployment and measurement, these frameworks can yield tangible results that increase the value of the company.

How does investing for impact help attract buyers?

- Scaled Impact-Driven Business Segments: Impact investors are focused on scaling business lines within companies that are most aligned with their particular impact objectives. By directing management focus and financial resources to these areas, impact-driven business segments experience significant expansion during the life of the investment. The most impactful segments within a portfolio company can prove to be the most scalable profit centers, leading to financial growth.

- Rigorous Impact Reporting: Firms that have rigorous processes around impact measurement are able to use reporting as a strategic tool during the exit process. Firms who set specific impact objectives prior to investment, collect data throughout the investment lifecycle, and report outcomes achieved as part of their reporting are able to demonstrate impact as a significant component of portfolio company value.

- Early Inbound Offers from Strategic Buyers: A common theme amongst exits analyzed was receiving early inbound offers from strategic buyers interested in the significant growth achieved and potential for future impact from portfolio companies. This is emblematic of the collinear nature of impact and financial returns at companies where ICM member firms have worked to effectively grow the core business.

How do impact-driven tools help maintain impact at exit?

- Strong Management Team: Impact investors often form mission alignment with management teams early in the investment process. Belief in management vision and their ability to create meaningful impact and financial return causes investors to prioritize buyers who will keep leadership as part of their offer. This continuity has the effect of impact remaining a key focus for the company post-exit.

- Impact Governance Guidelines: Through the use of legal tools and impact-specific covenants, ICM member firms can create formal post-exit governance procedures to protect for impact. Some firms also incorporate impact governance into board structure or create separate entities that are focused on impact measurement and reporting. Maintaining a position on a company’s board post-exit can also codify and preserve impact.

Initial Data Summary

Introduction

Before delving into stories of individual exits, a review of data taken across the broad ICM membership demonstrates the heterogeneity of overall exits. In March 2022, we asked ICM firms to compile a list of all of their exits to date and provide the following information for each exit: type of exit, industry of exited company, impact theme of exited company, earliest funding round, financial performance, impact performance, and the most important of the 10 drivers from the original Alpha in Impact report to determining the outcome of the exit.

At the time of the survey, ICM had 78 member firms. We received full or partial information on ~230 exits from 30 impact-focused market-rate investment firms. While we recognize potential bias in the data due to the limited sample size, we believe that the information gathered across a diverse range of exits and firms provides useful insights to understanding the composition and performance of exits by impact investors.

Impact Theme Breakdown of Exits

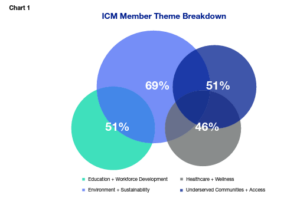

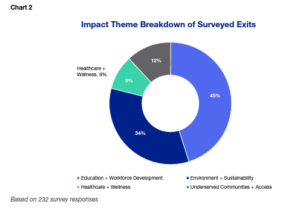

ICM member firms work across a range of industries, impact themes, and geographies. Some firms are explicitly focused on a single theme or impact vector, while others cut across a variety. Respondent survey data shows a heavy bias toward exits in the Education + Workforce Development and Environment + Sustainability categories. As the corresponding breakdown of impact themes across the entire ICM membership shows, this is largely a reflection of the overall makeup of the organization. Additionally, survey respondents with a large amount of exits tended to focus on the Education + Workforce Development impact theme. The gathered data might indicate that exits within the themes of education and the environment are more numerous due to the development and attractiveness of these sectors in recent market environments, with the pandemic and government funding as potential stimulants. Further research could confirm this.

Exit Type

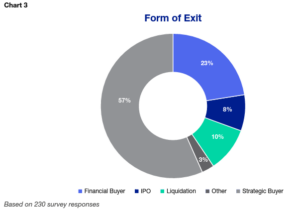

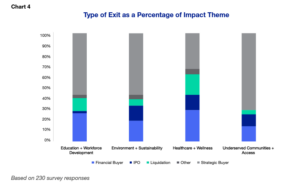

Another interesting outcome of the broad exit survey was the type of exits impact firms chose to take. Our surveyed exits revealed that exits to strategic buyers reflected nearly 60% of exits, with exits to financial buyers second at 22%. IPOs reflect a minority of exits from surveyed firms. Liquidations were also a small component and were mainly connected to unsuccessful investments in portfolio companies. The 3% “other” category were exits that took the form of debt repayment or refinancing, partial secondary exits, or levered buyouts by management. As the type of exit by impact theme breakdown shows, this distribution of exit type is relatively consistent across impact themes.

While our broad survey data reflects only a portion of all exits from impact-focused firms, our case study sampling and interviews with participating firms provided some insight into the preference towards strategic buyers. Based on anecdotal feedback from ICM members and stakeholders, at the time that most of these exits occurred, financial buyers with an impact lens comprised a comparatively small section of the buyer market. Given the dynamics of the exit process and impact-specific considerations, an exit to a traditional financial buyer may not have been viewed as a favorable outcome. The lack of large financial buyers was especially important for later-stage companies who have high valuations and would not be appealing to early stage or venture impact investors. In the current landscape, with the entrance of large private equity firms into the impact space, including Bain Capital, TPG, and KKR, it will be interesting to see how the landscape for exits to impact-focused financial buyers evolves in the future.

As our interviews revealed, there was often a preference toward exit to strategic buyers who were more able to grasp and place value on the impact and revenue potential of mission-driven companies. Strategic buyers also had the industry-specific tools and partnerships to successfully grow exited portfolio companies. Some, though not all, of fund managers interviewed actually placed preference on strategic buyers during the bidding and exit process in the hopes that a strategic buyer would be able to successfully scale the core business and retain the management team, two factors that relate to protecting the impact at exit.

Impact-focused companies, some in the form of PBCs (Public Benefit Corporations), have gained substantial public investor attention during their IPOs, despite IPOs reflecting a relatively small share of exits. We might expect more IPOs with larger, later-stage impact players in the market; however, that expectation is tempered somewhat by the short- to medium-term market outlook as of publication of this report in 2023.

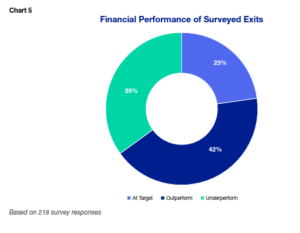

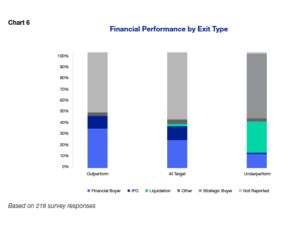

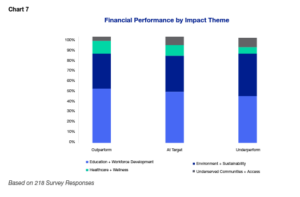

Financial Performance

When asking firms about the financial performance of their exits, we asked them to label the performance of each exit in terms of performance relative to their target for the investment. Each exit was labeled as either an outperform, at target, or underperform. The reference target could be a company-specific or a firm’s set hurdle rate, target IRR, or MOIC. 65% of exits reported by firms were at or above their financial target. As shown by the following two graphs, the difference in financial performance across exit types and impact themes is explained by the overall breakdown of exit type and impact theme (see Charts 1 and 2). As expected, liquidation was a prominent exit type for financial underperformance.

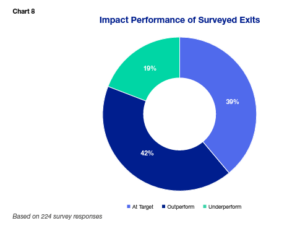

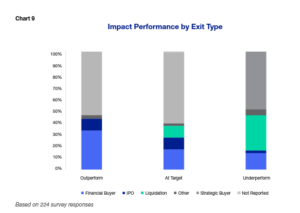

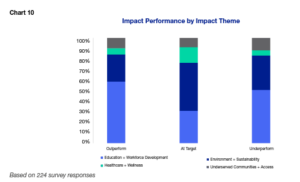

Impact Performance

Impact performance followed the same methodology. Firms were asked to label exits as outperform, at target, or underperform. Each firm has widely varying levels of impact measurement and reporting, with the target level of impact measured through specific KPIs or impact outcomes or else a more subjective indicator. We see a slightly higher level of performance in impact as compared to financial performance, with 81% of exits being reported as at or above target. For most reported exits, financial outperformance also translated to impact outperformance. However, we see that it is possible for an exit to meet impact targets despite financial underperformance. This could perhaps be an indication of less stringent measurement or hurdles for impact or instances where fund managers were satisfied with the impact achieved during the life of the investment but hoped for a more gainful financial outcome. It is possible that when more rigorous and consistently applied standards are applied to this same self-reported data, different responses would occur in regards to impact performance. Impact performance does not seem to vary meaningfully in relation to exit type and impact theme breakdown.

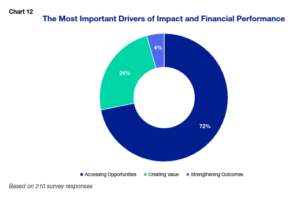

Impact Drivers (Based on Previous Alpha in Impact Report)

As part of our initial survey, we asked firms to list the most important driver of the 10 listed in the original Alpha in Impact report in determining the outcome of their reported exits. While these are certainly not the only drivers of exit outcome, a meaningful data set was a compelling opportunity to pressure test the relevance of the original 10 drivers. Not all respondents provided this information for all exits, but the aggregate overview of the most important reported drivers presents interesting observations.

Notably, the drivers from the Accessing Investment Opportunities portion of the 10 original drivers (find investment opportunities through mission-aligned networks, uncover investment opportunities through deep market expertise, align values with investees) are the most widely reported as most important driver for 72% of included exits. As compared to the seven listed drivers in the Creating Value and Strengthening Outcomes categories, the first three drivers are focused on activities that occur at the outset of the investment and demonstrate the importance of professional networks and value alignment with the portfolio company. Further research could probe the specific importance of impact networks and incubators to the ultimate outcome of investments. Additionally, as we see the growth of more codified impact reporting and measurement methodologies and the increased use of impact protecting financial and legal tools, value creation from impact may move further down the investment lifecycle.

Introduction: Exit Case Studies

While looking at overall exit data is helpful, each portfolio investment and exit process present their own nuances, challenges, and drivers of success. To interrogate the relationship between impact and financial value, we analyzed in-depth transaction data at the exit level. Firms opted into participation and were asked to select an exit where impact was most influential to the outcome on either the upside or downside. Keeping with findings from our broad survey, determinants of exit success spanned the investment cycle. Some cases focus more on value creation early in the life of the investment that led to a certain exit outcome. Others show choices closer to the ultimate exit that made all the difference.

A comprehensive survey preceded an interview, which probed transaction information around our three primary questions. Target selection questions included an understanding of the impact due diligence process, third-party impact assessment, and initial alignment with management. The impact tools portion of the survey covered the use of specific legal impact protection tools used by our report partners, Morrison Foerster, as well as other tools used by firms to create and maintain impact at exit. We also gathered exit-specific financial information, including the exit value of the firm’s stake, company valuation at the time of exit, hurdle rates, and deal IRRs.

While our data set was limited, we noticed the heterogeneity across impact investments in terms of size, stage, sector, length and instrument of investments. Points of commonality among case study participants were the use of a specific impact diligence process, alignment with management, and board member roles with the investee.

Exit case studies were constructed with information from an in-depth interview conducted with fund GPs as well as background information taken from the survey and other publicly-available information. Each case study is grounded in the drivers from the original Alpha in Impact report, with the three most important drivers for each exit listed at the end of the study. Financial and impact return summaries are included to demonstrate the magnitude of return beyond qualitative discussion. Information is shown subject to firm specific-disclosure guidelines. In some cases, additional legal disclosures specific to firms or investments are included. Finally, the case studies include any specific legal tools used during the investment and exit process. To learn more about these tools, please see page 45 in the Impact Tools section of this report.

Though self-reported, our case studies span a diverse range of impact themes, firm sizes, and exit types. We believe that, in sum, they provide a unique view into the most salient determinants of outcome at exit for impact investors.

Employee Ownership: Impact Tools Spotlight

Introduction to Employee Ownership

As the previous case studies have illustrated, impact firms employ a variety of tools throughout the investment lifecycle to create and protect for impact. The introduction of broad-based employee ownership programs at portfolio companies is a tool increasingly used by firms to align incentives and address the question of impact and equity at the root level. These programs are designed to be scaled broadly across companies through the development of stock plans that allow for employees at all levels to gain a stake in the company. Plans give employees a share of distributions from investors, including a portion of proceeds in the event of an exit. Broad-based, equity-focused employee ownership programs differ from typical employee ownership plans in traditional private equity and venture investments by widening the range of employees who have access to equity grants beyond the normal scope of senior management and early employees at startups. They also generally expand the overall share of the company that is owned by non-management employees from ~5 – 10% to ~20 – 30%.

Employee ownership has the potential to produce several key benefits, including increased employee engagement and motivation, improved productivity and company profitability, higher retention rates, and potential tax benefits. As impact investors, ICM member firms often view employee ownership as a means of increasing social equity more broadly and ensuring that those who contributed to the success of the company are able to participate meaningfully in its financial upside.

However, implementing these programs can come with challenges, including convincing existing investors in the company and fund limited partners to increase ownership share to employees. Making sure employees have access to adequate financial literacy and ensuring that the employee engagement remains high are also necessary for program success. Additionally, there are often structural factors within a firm and an industry that influence the probability of success. For example, industries with traditionally unstable or cyclical workforces (such as some retail businesses) may not reap the full benefits of the program. Companies with a highly distributed workforce may also face challenges in designing a successful program.

Supporters of broad-based ownership programs acknowledge that they do not succeed in a vacuum. Ownership Works12 is a non-profit organization that partners with private capital investors and independent company leaders to help them implement broad-based equity ownership. The organization was founded with the goal to provide meaningful wealth-building opportunities for low- and middle-income families and promote responsible business practices. Ownership Works provides company-customized tools to structure and implement equity plans and create financial education and cultural programming. The organization also works to combat the misconception that employees will not understand the value of equity. Per the organization, engagement and education are a necessary part of the work.

Employee ownership has concrete implications during the exit process. Firms who implement employee ownership programs successfully accelerate company growth and ultimately influence financial performance at exit. Companies with meaningful employee engagement foster an inclusive and productive culture and also develop a resilient workforce and business model. These qualities make them attractive to a variety of buyers during any market conditions. From an impact perspective, firm and company leaders can be concerned with retaining this positive, ownership based culture post-exit. Employee ownership could be seen as a way to incorporate impact into a company at the root level, paying dividends beyond the equity payout. When employees hold a fair share of the company pre-acquisition, successful exits have the ability to meaningfully transform lives, not just for high level senior management, but for low- to middle-income employees throughout the company.

Legal Tools to Protect Impact on Exit

As indicated by the case studies discussed in this report, a growing number of impact investors are utilizing legal provisions and tools to maintain mission and impact in connection with exit events. Outlined below are examples of such legal provisions and tools that are being incorporated into deal documentation. Based on the case studies and survey results, the use of these provisions vary among companies and impact investors depending on a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, the level of co-linearity between a company’s impact and financials, familiarity with such tools, and an investor’s leverage. Some tools, such as impact diligence and highlighted mission in sale prospectuses, are becoming quite common. Other tools, such as tying earn-out payments to achievement of impact metrics post-closing, are less often used, if at all, among those surveyed.

Whether or not a particular impact provision should be included in definitive legal documentation is something that must be decided on a deal-by-deal basis. However, similar to how including protective provisions related to economic and governance rights are common and can maximize an investor’s financial return from a company, including protective provisions related to impact can improve both the financial and impact performance of a company. In scenarios where a mission-aligned investor retains a minority stake in a company after a liquidity event, consent rights related to deviations from the mission or use of a benefit corporation can prevent mission drift. Even if an impact investor completely exits a company, provisions related to post-closing payment of proceeds or restrictive covenants can be tied to impact, incentivizing the new owners to maintain impact. As with non-impact legal provisions, the goal of these provisions and tools is to align incentives among relevant stakeholders in a manner that clearly and precisely allocates risk and responsibility for maintaining impact.

Tools Used Preparing for a Transaction

Maintaining mission and impact can start with pre-transaction actions, including the following examples:

- Highlighting Mission in Bid Solicitation. Sellers use an information memo to emphasize the mission of a company in order to filter for buyers who are mission aligned.

- Impact Diligence. Buyer’s diligence includes ESG issues including, but not limited to: (i) increased emphasis on benchmarking objectives (i.e., is the company tracking ESG metrics and setting benchmark goals); (ii) focus on supply chain activities, including analysis of what is being monitored and reported and use of third-party verification; and (iii) climate risk scenarios.

- Reverse Impact Diligence. Sellers conduct reverse due diligence on potential buyers, for example, diligencing their ESG practices, prior acquisitions, and gathering information about the quantitative impact metrics used by buyers.

- Impact Corporate Form. Multiple states now offer new corporate forms to address balancing social mission against the pursuit of profitability that embed a company’s mission into its governing documents (e.g., the Delaware public benefit corporation (“PBC”) and the California benefit corporation). A prior ICM report, “Legal Innovations for Impact Investing,” discusses these alternative corporate forms in more depth.15

- Licensed IP. Valuable IP is held by a mission-aligned founder or affiliated entity (e.g., for-profit, non-profit, or trust) and licensed back to the company with mission lock covenants. Holding IP outside of the company may have a negative impact on valuation and can be very difficult to reverse if the IP is held by a non-profit. However, if IP is held by a founder, there is more flexibility to change the impact covenants (and reduce the risk of impact on valuation) than if IP is held by a public charity. Royalties can be paid on a sliding scale to incentivize mission alignment – if a company adheres to the impact covenants, royalty payments are lower, but if they deviate from the mission, they are increased.

- Sustainable Prospectus. Sellers can pursue a sustainable public equity offering.

Tools Used in Terms of Sale Documents

Definitive transaction documents can also include impact and mission-related tools and provisions:

- Representations and Warranties. ESG representations and warranties on behalf of the company (e.g., good governance practices, human capital treatment, energy and sustainability, etc.). Sellers can also require a buyer to make representations and warranties regarding their past impact and ESG practices.

- Earn-out Payments. Contingent payments to sellers based on achievement of impact metrics post-closing.

- Penalty Payments. Reverse earn-out payments, release of escrowed proceeds, vesting acceleration for founders, or other penalties if the company materially deviates from mission within certain timeframe after closing.

- Covenants. Ongoing-third party evaluation and/or certification for a certain timeframe after closing. For companies that have sustainability or impact advisory boards, it may also require the buyer to maintain the board after closing, or such a board could be formed as part of the exit.

- Termination of Restrictive Covenants. Sellers are released from restrictive covenants in the event of a deviation from mission.

Tools Used for Governance

Certain governance provisions can be implemented in order to protect and maintain impact during an investment period:

- Consent Rights: Mission-oriented equity holders can have a consent right over actions that affect the Company’s mission orientation, such as (i) converting from a public benefit corporation to a standard corporation; (ii) amending a PBC’s public benefit set forth in their charter; (iii) materially modifying agreed-upon impact goals and targets; or (iv) taking other actions that may indicate mission-drift, such as entering into new lines of business or failing to achieve stated impact goals.

- Golden Shares: A company can incorporate “mission equity” in the form of a single share or separate class of shares with certain protected veto/voting rights related to impact built into a company’s charter (“Golden Share(s)”). The Golden Share(s) can be held by various third parties, including (i) individuals, (ii) a Delaware Public Benefit Limited Liability Company, (iii) a Delaware perpetual purpose trust; (v) a non-profit, or (v) a cooperative. The Golden Shares generally do not weigh in on daily operations, but will have rights over certain corporate actions, including veto rights on a limited or broad set of key actions (e.g., changing the public benefit or mission or converting out of a PBC (if applicable), amending organizational documents, board composition, approval of share transfers or liquidation, etc.). In general, the broader the approval rights, the greater potential impact on valuation.

- Exit Rights. Mission-oriented equity holders can have exit rights in connection with a failure to meet certain impact-based targets or maintain mission-driven structures, such as a redemption or put right if the company has not achieved carbon-neutrality after a certain number of years, or if a PBC ever converts into a standard corporation. Such rights allow mission-based investors to exit an investment that no longer aligns with their investment goals, while also (depending on the price/terms set for such exit right) carrying a heavy stick in enforcing mission-lock of the company.

- Oversight. A board can form an “Impact” committee to oversee impact and reporting, which committee has certain veto rights in order to ensure mission is being considered in relevant decision-making. Mission oriented equity holders can have the right to have their director designee be appointed to this committee.

- Reporting. Requirement of third-party evaluation and/or certification, and reporting to investors/ equity holders on the company’s impact performance (note that PBC’s are required to provide biannual public benefit reports to their stockholders).

- Compensation. The go-forward compensation of key executives and management is tied to the achievement of mission-based targets, including in connection with annual bonuses or the vesting of equity.

Conclusion

Mixed Market Signals

Sixteen years after the term “impact investing” was first coined in 2007, the industry has reached a long-sought after inflection point. The first wave of fund managers seeking superior returns now have track records that can be examined more objectively and in aggregate, in turn creating expectations for companies, competitors, emerging managers, and limited partners regarding the range of financial outcomes that can be achieved by investing with an impact lens. The early evidence from this and prior studies suggests that the upper end of that range puts impact private capital on a competitive footing vis-à-vis traditional investing.

Is past performance a predictor of future success? The picture is somewhat complicated by the uncertain market as of the publication of this report in Spring 2023. After a decade of seemingly endless expansion in private equity and venture capital, expectations have cooled and capital flows have slowed. According to Pitchbook, venture capital firms in the United States raised an amount in Q1 2023 that is only slightly more than they raised at the same time in 2017 – and a 73% drop compared to the first quarter of 2022. On the other hand, company valuations are also showing signs of rationalization, presenting an opportunity for impact funds with significant “dry powder” to deploy capital on more attractive terms.

That said, other market forces such as increasing climate-related financial risks, growing consumer demand for environmentally conscious or socially responsible products and services, and government incentives like the landmark Inflation Reduction Act may all work to further support strong impact investor returns. The landscape for private markets over the next ten years will clearly look different than the unprecedented growth of the last decade. But whether this is a net positive or negative for strong outcomes in impact investing remains to be seen.

Exits Evolution

Even in the midst of mixed market signals, we can generate some informed hypotheses based on the analysis in this study. Over the timeframe of the exits analyzed in this report, financial buyers (vs. strategics) with an impact lens comprised a comparatively small section of the market. Today there is an influx of large private equity firms moving into the impact investing space. For this reason – and because the pace of IPOs is unlikely to pick up during economic uncertainty – it’s reasonable to predict more exits to impact-focused financial buyers in the next five years. Assuming these “impact sleeves” hold themselves to high impact standards, this could be an auspicious development for the sustainability of positive environmental and social outcomes over time.

Impact Implications

While this research suggests a strong relationship between impact and financial performance at exit, it also suggests that it is possible for an exit to meet impact targets despite financial underperformance. This could be an indication of less stringent measurement or hurdles for impact, instances where fund managers were satisfied with the impact achieved during the life of an investment but hoped for a more gainful financial outcome, or problems accurately predicting the expected impact over the lifetime of an investment. For additional context, this study was limited to an analysis of ICM member funds, all of which measure and manage their impact according to the membership association’s “Fundamentals.” The Fundamentals are four core practices that all members – regardless of AUM, investing stage, sector, or asset class – commit to demonstrating to ICM staff and fellow members within two years of joining the network. These are processoriented practices; they are intentionally not prescriptive in terms of what is measured or how a fund manager should weight one impact KPI over another. To be meaningful, these should be informed by each underlying business.

But the fact that even for these investors, some investments met (or exceeded) impact expectations while underperforming financially underscores the more pernicious challenges with impact measurement and management. An investor who moves the impact goalposts or doesn’t acknowledge the context in which the company is operating can too easily make a substandard impact story come across as a home-run. On the other hand, foisting unrealistic expectations on impact investors and companies may also perversely incentivize companies to busy themselves counting things that don’t matter – sometimes referred to as “performative” analytics. Furthermore, focusing on impact metrics that are decoupled from the core business may mean the company does not scale as quickly or effectively. Less scale can in turn translate into less net positive impact over time. In the rush to standardize, we must acknowledge there will always be some inherent subjectivity as different individuals weight or value different kinds of impact, differently – even within a single company’s leadership team. And sometimes a change in the macro context (like a pandemic or an overdue recognition of structural racism) necessitates a pivot or re-weighting.

Cognizant of these tensions, progress can still be made on impact management in ways that reinforce strong outcomes at exit. From our vantage point:

- Companies and investors must collect data in a more objective, consistent, and accurate way, with an eye toward what is both truly meaningful for decision-making, but also what is feasible to implement.

- What impact data is collected, and how, should be informed by a broad set of stakeholders including workers, customers, and communities affected by company’s operations and the products or services it sells.

- Legal tools should be used by both impact sellers and buyers, and in IPOs, to ensure continuity of impact during and after exit, and to ensure compliance.

Several organizations are playing a lead role in engendering this progress. Impact Frontiers is on the vanguard of helping private capital investors establish and weight impact factors and integrate financial and impact considerations on the company and portfolio level. The Impact Principles – which align strongly with ICM’s own Fundamentals, and which many in the network are signatories to – specifically call out the need for managers to conduct exits considering the effect on sustained impact, consistent with fiduciary concerns.16 Another growing practice with implications for stronger exits is independent verification of impact. BlueMark is the leading provider in the market offering third-party verification. At the time of publication, 34% of ICM members are using independent verification to objectively gauge their impact process or outcomes.

What’s Next

This report adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating that impact-focused strategies can meaningfully contribute to financial returns, and that those returns are competitive with traditional investing strategies. It also points to a wider variety of legal tools being used by both fund managers seeking mission aligned exit options, and limited partners who seek confidence that impact obligations – not just financial returns expectations – are being met.

Ideally future studies will include a larger set of funds and exits for analysis, with greater diversity in geography, asset class, thematic focus, exit type, and assets under management. Research is also warranted to better understand value creation during the holding period, cited by investors as the most important determining factor in 24% of the exits analyzed here. As we see the growth of more codified impact reporting and measurement methodologies and the increased use of impact-protecting financial and legal tools, value creation from impact may move further down the investment lifecycle.

Download the complete report here.

Print

Print