David A. Cifrino is Counsel at McDermott Will & Emery LLP. This post is based on his MWE memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, Roberto Tallarita and Stakeholder Capitalism in the Time of COVID (discussed on the Forum here) both by Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, Roberto Tallarita; Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock (discussed on the Forum here) by Leo E. Strine, Jr.; and Corporate Purpose and Corporate Competition (discussed on the Forum here) by Mark J. Roe.

New regulations expected to be adopted in 2023 will result in exponential growth in the amount of environmental, social and governance (ESG), i.e., sustainability, data generated by reporting companies and available to investors.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is expected to adopt final rules requiring detailed disclosure by companies of climate-related risks and opportunities by the end of 2023. The newly-formed International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is expected to adopt two reporting standards in June: one on climate-related risks, and a second on other sustainability related information. Regardless of how much harmonisation there will be between these and other ESG disclosure standards, it is clear that mandatory, standardised sustainability reporting by corporations will increase significantly worldwide over the next few years.

The Data Driven and Rapidly Consolidating Global ESG Investing Ecosystem

The demand for enhanced ESG disclosure is intense. Globally, overall ESG investing is massive, having grown as much as tenfold in the last decade. Morningstar, Inc. estimated that total assets in ESG designated funds totaled more than US$3.9 trillion at the end of September 2021. The evolution in ESG investing has been accompanied by exponential growth in the amount and types of data available for ESG investors to consider. The number of public companies publishing corporate sustainability reports grew from less than 20 in the early 1990s to more than 10,000 companies today, and about 90% of the Fortune Global 500 have set carbon emission targets, up from 30% in 2009.

The world’s largest asset manager, Blackrock, Inc., noted in a comment letter to the US Department of Labor regarding pension fund regulation that, as ESG data has become more accessible, the firm has developed a better understanding of financially relevant ESG information, and ESG funds that incorporate financially relevant ESG data have become more common. BlackRock stated that its systems for ESG analysis have access to more than 2,000 categories of ESG metrics from various ESG data providers. The firm concluded that, because of the greater volume of ESG-related disclosures by companies and third party ESG vendors, together with advancements in technology, “the use of ESG data to seek enhanced investment returns and/or mitigate investment risks has become more sophisticated.”

Much of the ESG data available to investors historically has been obtained through voluntary cooperation, from companies either answering survey questionnaires or publishing sustainability reports based on one or more of dozens of frameworks and reporting standards created by various non-profit organisations active in environmental and social causes. Voluntary disclosure of ESG information over the past three decades has been highlighted by the development of several key reporting standards and frameworks.

The development of the Global Reporting Initiative in the 1990s as a standard reporting framework for

corporate social responsibility reporting was a major step in promoting reporting focused on both ESG issues material to a company and that company’s external impacts on outside communities and the planet.

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) created in 2017 by the G20’s Financial Stability Board, and widely adopted around the world, recommends disclosure regarding climate related governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets specific to the risks to a company presented by climate change.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), modeled on the Financial Accounting Standards Board, which oversees generally accepted accounting procedures in the United States, was formed in 2011 with a focus on ESG factors material to a company on an industry by industry basis. SASB has developed standards for 77 industries that identify and measure financially material, decision useful and actionable ESG factors important to long-term value creation.

In 2014, the European Commission adopted a financial directive that requires certain large companies to disclose information on the way they operate and manage social and environmental challenges. The directive was intended to help investors and other stakeholders evaluate the non-financial performance of large companies, and encourage these companies to develop a responsible approach to business. It applies to large public-interest companies and requires information related to environmental and social matters, treatment of employees, human rights, anticorruption, and board diversity.

Supplementing the directive, in 2019 the Commission published new climate reporting guidelines for companies that integrate the TCFD’s recommendations. To address shortcomings in the Non-Financial Reporting Directive, on 10 November 2022, the European Parliament substantially increased mandatory sustainability disclosure requirements by adopting a new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive as discussed in more detail on p.6.

The United States has been far slower than Europe in regulating ESG disclosures. Other than long-standing financial, risk, and litigation disclosure requirements appliable to public companies regarding environmental issues and, since 2020, material aspects of a company’s human capital management, there have been virtually no mandatory requirements and only limited regulatory guidance for disclosure on sustainability issues by public companies listed or based in the United States.

In 2010, the US SEC issued guidance to reporting companies on disclosure of material climate-related risks that should be disclosed under existing SEC disclosure rules. Finding that this guidance was insufficient, on 21 March 2022, the SEC proposednew rules to require companies filing reports and securities registration statements with the SEC to provide detailed information about their handling of climate related risks and opportunities, including climate-related governance, strategy, risk management, metrics, and goals based on the TCFD framework. The proposed rules will also require companies to measure and disclose greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in accordance with the GHG Protocol methodology, the most widely known and voluntarily used international standard for calculating GHG emissions.

The SEC proposal notes that several jurisdictions have already adopted disclosure requirements in accordance with the TCFD’s recommendations, including Brazil, the European Union, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Consolidation of the ESG Ecosystem

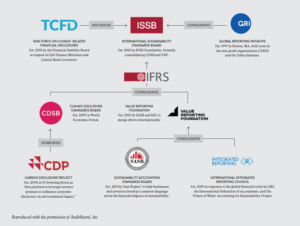

In November 2021, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IRFS) Foundation—which administers the IFRS financial accounting standards that are used in most jurisdictions other than the

United States—announced the formation of the ISSB to develop a comprehensive global baseline of sustainability disclosure standards. The ISSB will sit alongside the IRFS International Accounting Standards Board, and it can be expected that jurisdictions that require financial reporting based on IFRS standards will also require sustainability reporting under ISSB standards. As depicted in the graphic below, there is a rapidly accelerating consolidation into the ISSB of the most internationally significant existing global sustainability disclosure frameworks and standards, including those of the SASB.

Taken together, this consolidation of the ESG disclosure ecosystem, the continued enhancement and standardisation of ESG data, and the analyses it promises to yield, should enable market participants to more precisely evaluate when ESG factors are relevant to the creation of long-term value, which in turn can facilitate more confident ESG investment decisions.

New Regulations Addressing Greenwashing

In addition to this massive and widespread regulatory momentum to require greater volume, consistency, and reliability of corporate ESG disclosures, there is also increasing regulation designed to mitigate “greenwashing” where the potential social and environmental benefits of a fund’s ESG investment strategy are overstated or even nonexistent.

In Europe, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) has, since 2021, required EU investment firms to disclose their approach to the consideration of ESG factors in their investment

decisions, and to make disclosures for investment products that take into account ESG factors. As discussed in more detail on p.9, the SFDR sets forth the following disclosure categories into which

financial products must fall:

- Funds that address ESG risks but have no sustainability goals (Article 6 funds)

- Funds that promote ESG characteristics (Article 8 funds)

- Impact funds that have intentional and measurable sustainability objectives (Article 9 funds).

The SEC has pending proposed anti-greenwashing rulesapplicable to investment firms. These provide that only funds with an ESG purpose would be permitted to label themselves as such. The new rules would also require mandatory disclosures for ESG-focused funds to enable outside parties to confirm whether or not a purportedly ESG-focused fund is in compliance with its stated investment purpose.

Similar to the SFDR, these new rules would create three categories of ESG funds:

- Integration Funds, which would be required to disclose how ESG factors are incorporated into their investment process, plus any non-ESG factors

- ESG-Focused Funds, which identify ESG factors as a significant or principal consideration and are

therefore required to make a more detailed disclosure - Impact Funds, which seek to achieve a particular ESG impact and are required to disclose how the fund measures progress towards its stated objectives.

The categorisation of ESG funds on a standardised basis under new European and US funds regulations can be expected to significantly mitigate the problem of inconsistent terminology and nomenclature as to what is and isn’t fairly categorised as an ESG investment. This will potentially facilitate more definitive conclusions on the financial performance of various ESG investment strategies.

Print

Print