Ben Bates is a Research Fellow at the Harvard Law School Program on Corporate Governance. This post is based on his recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang; Dancing with Activists (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch; and Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System (discussed on the Forum here) by Leo E. Strine, Jr.

The Dodd-Frank Act, passed in 2010, directed the SEC to tighten the reins on private equity and hedge fund advisers by setting up a monitoring and reporting system. When the SEC proposed new rules to implement the Act’s mandate, it triggered a wave of criticism. The SEC had predicted that advisers would spend only an additional $25,000 to $65,000 per year on compliance costs (SEC Release No. IA-3222, pp. 151 – 52), but the advisers themselves complained that, in reality, complying with the new regulations would cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars per year and have a negative impact on their business.

The huge gap between the SEC’s and advisers’ cost estimates is concerning because the SEC routinely justifies its rules on cost-benefit grounds. If the SEC is naïve about how burdensome its rules are, it risks overregulated and slowing down economic growth. On the other hand, it is hard to know how much to trust industry members’ cost estimates. After all, they have an incentive to exaggerate to convince the SEC to loosen up its regulations.

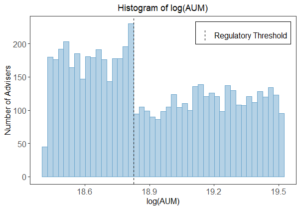

In a new paper, I estimate the cost to private fund advisers of complying with the SEC’s Dodd-Frank-era rules to see whose predictions were more accurate. My estimation strategy takes advantage of a carve-out in the Dodd-Frank Act that lets private fund advisers with less than $150 million in assets under management (AUM) claim an exemption from the most burdensome regulations. The carve-out creates an incentive for smaller advisers to “bunch” beneath the $150 million threshold to save on compliance costs. For many advisers, however, bunching comes at a cost. Advisers’ compensation is largely based on their AUM, so staying small means taking a pay cut for advisers who could raise funds with more than $150 million. Understanding this tradeoff between pay and compliance costs allows me to estimate compliance costs based on the extent to which advisers choose to bunch beneath the $150 million threshold (Alvero, Ando & Xiao 2023).

My main conclusion is that the SEC predicted compliance costs far more accurately than most industry commenters. Using administrative data from the SEC, I document that a statistically significant number of advisers bunch beneath the $150 million threshold. Based on the level of bunching I observe, I estimate that the average cost of complying with the SEC’s private fund rules was $54,000 per year from 2013 to 2022. This figure sits comfortably within the SEC’s predicted range but is far below most industry-provided estimates. Additionally, I find that compliance costs appear to have been somewhat higher for private equity fund advisers (around $84,000 per year) than for hedge fund advisers (around $30,000 per year).

One limitation of my bunching estimates is that they do not capture compliance costs that advisers are able to pass on to their investors. This leaves open the possibility that compliance costs have been much higher than the SEC predicted and investors have been bearing the brunt of those costs. To test whether this is the case, I examine data on monthly net hedge fund returns to see if investors’ returns drop when their fund adviser stops claiming the AUM-based exemption. After controlling for fund size, I find no evidence that investors’ returns decrease when their adviser gives up the exemption. This result seems to suggest that whatever compliance costs advisers may be passing on to their investors are not substantial enough to noticeably reduce returns.

Another limitation of the bunching approach is that I cannot rule out the possibility that the bunching I detect is being driven by something other than compliance costs. For instance, it is possible that advisers claim the exemption because the lighter regulatory environment allows them to exploit their investors by charging excessively high fees or exaggerating their performance. This possibility does not change my main conclusion, though it does suggest that my estimates should be viewed as an upper bound on real compliance costs. Even so, it is important to understand what drives advisers’ bunching in order to evaluate the wisdom of having a size-based regulatory exemption in the first place. After reviewing the literature on private fund adviser misconduct (Brown, Gredil & Kaplan 2019; Honigsberg 2019; Jiang et al. 2023), I conclude that the bunching I observe is difficult to explain under an investor exploitation hypothesis, suggesting that the bunching is being driven mainly by compliance costs.

In addition to my bunching analysis, I present a set of results that sheds additional light on advisers’ behavior around the regulatory threshold. First, I show that relatively few advisers maintain exempt status for a long period of time. Rather, most advisers give up the exemption or stop reporting to the SEC altogether within 4 to 6 years after their first report. Second, I show that, on average, advisers’ assets increase sharply in the year they stop claiming the regulatory exemption. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that advisers give up the exemption when they know they can raise a big enough fund to be worth it, not when they accidentally slip over the $150 million threshold. Third, I show that some advisers who could claim the exemption refuse it. I also show that the percentage of advisers who refuse the exemption has decreased over time and advisers who refuse the exemption are more likely to report assets exceeding $175 million within a few years.

Taken together, my findings have several important implications for policymakers. First, my cost estimates should give the SEC (and courts reviewing SEC rulemakings) confidence in the SEC’s ability to estimate compliance costs. At the same time, my estimates suggest that cost estimates provided by members of regulated industries should be met with some skepticism. Second, my findings serve as a reminder that regulatory costs can have a measurable effect on the behavior of regulated parties, even when the costs are relatively small. Third, and finally, my research suggests that the SEC’s private fund rules affect private equity and hedge fund advisers quite differently. The SEC may therefore need to adjust its approach to overseeing different types of funds to ensure that it is providing the greatest possible protection to investors at the lowest necessary cost.

Print

Print