David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting, Emeritus; and Brian Tayan is a researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Lucky CEOs and Lucky Directors (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Yaniv Grinstein, and Urs Peyer; and Paying for Long-Term Performance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Jesse M. Fried.

We recently published a paper on SSRN (“CEO Succession and The Walt Disney Company”) that examines long-running succession issues at The Walt Disney Company.

CEO succession planning is a critical exercise for any organization. All companies, regardless of the status and performance of their CEO, are expected to have a plan in place to replace that individual when the need arises. This includes the identification of internal and external candidates (including an “emergency” candidate if necessary), development programs for internal executives, mentoring and feedback, and regular review and discussion among the board and with the sitting CEO. Indeed, survey data shows that directors recognize CEO succession planning as one of their most important oversight responsibilities, and most believe they dedicate sufficient time and effort toward it.

And yet, experience clearly demonstrates that many companies fail to successfully handle the transition from one CEO to the next. They appear either unprepared for a transition to occur, unable to identify a successor, or unable to smoothly transfer leadership from one individual to another. What are the causes of this breakdown?

While the overriding problem is often a failure to plan, organizational factors can contribute. In some cases, the board does not properly understand how the skills needed to manage the company in the current setting differ from those of the recent past. The board might not recognize the leadership potential of candidates, organizational fit, or how to make tradeoffs when comparing the strengths and experience gaps of candidates. The planning process can become derailed when the board does not own the process, deferring too much to the outgoing CEO whose personal opinion—while important—is not the determining factor. The sensitivity of the topic—coupled with the diverse array of personalities, preferences, levels of assertiveness, and candor of the individuals involved—can disrupt the flow of unbiased information needed to make an independent assessment. Public scrutiny can exacerbate these problems, with shareholders, stakeholders, and other observers offering opinions that are not always fully informed or objective, with the pressure they exert on the board harming the decision-making process.

The challenges to a careful, deliberate, and well-scripted succession process are illustrated by The Walt Disney Company.

From Eisner to Iger

Robert Iger was named the CEO of The Walt Disney Company in 2005. His appointment, however, was not assured prior to its occurring.

Iger took over from Michael Eisner, whose 21-year tenure at the top of the company was at first stellar and later tumultuous. Eisner became CEO of Disney in 1984 after successfully leading Paramount Pictures as president and chief operating officer. Over the following decade, Eisner transformed Disney with a string of box-office hits (under studio chief Jeffrey Katzenberg), domestic and international expansion of the company’s iconic parks division, and the acquisitions of Miramax Films (1993) and Capital Cities/ABC, which included majority control of ESPN (1996). The company’s stock increased more than 30-fold during this period.

The latter years of Eisner’s tenure were more challenged. In 1994, Frank Wells, the company’s president and chief operating officer with whom Eisner enjoyed a close relationship, died in a helicopter accident. Eisner struggled to replace Wells, first passing over Katzenberg (who subsequently left to co-founded DreamWorks) and then turning to Michael Ovitz (head of Creative Artists Agency). Ovitz turned out not to be a great fit for the company, and left 16 months later. Disney’s decision to honor a separation agreement with Ovitz—valued at $140 million—embroiled the company in a legal dispute with shareholders that was eventually upheld by the courts. Eisner left the position of president vacant for several years, eventually filling it with Robert Iger in 2000.

During the final years of Eisner’s tenure, Disney’s performance stalled. The studio division struggled to produce hits, the newly acquired ABC network faltered, Disney’s foray into Internet services failed, and the company’s relation with key partners—including Pixar Animation, which Disney did not own but whose films it distributed—soured. By 2004, the company’s stock price was little changed from where it stood 10 years before.

Board members Stanley Gold and Roy Disney—nephew of the company’s founder and holder of 16.5 million shares—quit in protest and organized a campaign against Eisner’s reelection to the board at the 2004 annual meeting. With 43 percent of shareholder votes withheld, Eisner resigned as chairman, and the company separated the chairman and CEO roles. Six months later, the board announced it would launch a search process to name a new chief executive by summer 2005.

While Iger was the logical CEO candidate—and indeed, Eisner publicly called him his “preferred choice”—he had a few strikes against him. First, it was not clear to what extent the company’s poor performance in previous years (though recently improving) should be attributed to his leadership. Second, the investment community was not certain how Iger would perform independent of Eisner. Third, while Iger had deep experience in television production, he had much less experience in the creative side of the business that was core to Disney’s business model. According to one commentator, “Little in his past inspires confidence that Iger can do it all.” According to others, “Mr. Iger has never been seen as a sure thing for Mr. Eisner’s job, even though he clearly has wanted it.” In the words of one institutional investor: “They should not just anoint a member of the same old team.”

The board made assurances that the search process would be thorough and objective: “[Iger] is an outstanding executive and the board regards him as highly qualified for the position. However, the board believes that the process should include full consideration of external candidates as well.” The company’s independent chairman later added, “We approach this decision in good faith, with open minds. There has been no prior determination. There are no preconditions.”

In February 2005, Iger was named CEO. Reaction was mixed. Harvey Weinstein, who ran the Miramax division, was highly supportive, saying, “I’ve had a great working relationship with Bob Iger and think he’s a terrific choice as CEO.” Tom Murphy, Iger’s former boss at Capital Cities/ABC, described him as having “unbelievable energy and discipline.” On the other hand, pension fund CalPERS was “disappointed”: “Iger seemed to be hand-picked by Eisner, and our concern is that there will be more of the same.”

These concerns were exacerbated when reports leaked that, despite assurances otherwise, the board had not interviewed any external candidates. One prospective candidate—Meg Whitman, at the time CEO of eBay—reportedly pulled out of the process after deciding the board had settled on Iger. Other potential candidates—including senior executives at Time Warner, News Corp, Viacom, Yahoo!, and The Gap—were uninterested. Dissident directors Gold and Disney slammed the search process as a “sham”:

We find it incomprehensible that the board of directors of Disney failed to find a single external candidate interested in the job and thus handed Bob Iger the job by default. The need for the Walt Disney Company to have a clean break from the prior regime and to change the leadership culture has been glaringly obvious to everyone except this board. … The inescapable conclusion here is that Michael Eisner picked his own successor, in contravention to the expressed wishes of the shareholders. The board rolled over and played dead.

Iger’s Early Years

The criticism was short-lived. Iger proved to have the strategic, operating, and leadership skills to bring Disney into a new era.

In management style, he was the “un-Eisner.” Whereas Eisner was creative, hands-on, sociable, and highly public—favoring a centralized management approach—, Iger was low-key, diplomatic, self-effacing, and politically astute—favoring decentralization and accountability for division leaders.

Iger’s first move was to revitalize the animation division—not by rebuilding from within—but by negotiating to acquire Pixar for $7.4 billion. To signal the extent to which he was willing to go to transform the creative side of the business, Iger agreed to install Pixar executives Edwin Catmull and John Lasseter as heads of both Pixar and Disney animation. Iger explained, “I want to return Disney to greatness in this area, and this was the way to do it fastest.” The deal made Steve Jobs Disney’s largest individual investor and gave him a seat on the board. Iger followed by purchasing Marvel for $4.3 billion, and Lucas Film (with the iconic Star Wars franchise) for $4.05 billion.

Iger also reorganized the company around “franchises.” Instead of producing individual films, the company’s creative effort shifted to developing franchises—specific Disney, Pixar, Marvel, or Lucas concepts—that could be extended across all Disney properties (film, television, parks, and consumer products) to amplify their value. Iger prioritized investment in technology to ensure that Disney content was available in new digital formats (such as the Apple iTunes store). He also pushed international expansion—moving into Russia, China, India, and other markets with local content, and initiating what ultimately grew to a $5.5 billion investment in Disneyland Shanghai.

“There are a lot of companies that focus on content and a lot of companies that focus on technology, but I think Disney is one of a few companies that do both equally,” commented board member Sheryl Sandberg.

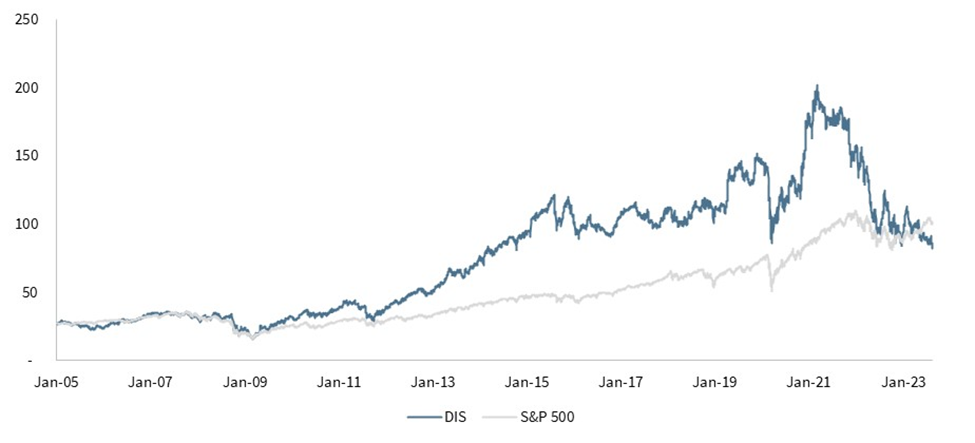

The result was a return of momentum. Disney’s stock price, which had stalled in the $30 range, pushed to new heights, far outpacing the market (see Exhibit 1). According to Steve Jobs, “The amount of energy and passion at Disney has increased dramatically.” According to former critic Stanley Gold: “[Iger’s] got the company working like a team again,” calling the change “impressive.” One newspaper journalist called Iger a “blockbuster CEO.”

Succeeding Iger

With the flywheel turning, Disney took the unusual step in 2011 of announcing that Iger would retire as CEO in 2015—four years in the future. He was 60 years old at the time.

The timing puzzled some: “It’s wise for Disney’s board to have a very clear succession plan,” observed one analyst, although it is “a little surprising given he’s still a young-ish CEO.” The presumed front runners were CFO Jay Rasulo and head of theme parks Tom Staggs, the two of whom had swapped roles in 2009 as part of a planned job rotation.

At the same time, Disney announced that Iger would become board chairman at the upcoming annual meeting, combining roles that had been separated seven years before during the controversy over Eisner. The company characterized the move as one that would keep Iger with the company as long as possible while carefully lining up a successor. “We were extremely anxious to have him continue,” explained Disney Chairman John Pepper. The influential proxy advisor Institutional Shareholder Services accused the board of reversing its “commitment to independent board leadership without transparency or shareholder input. Public pension officials echoed the criticism.

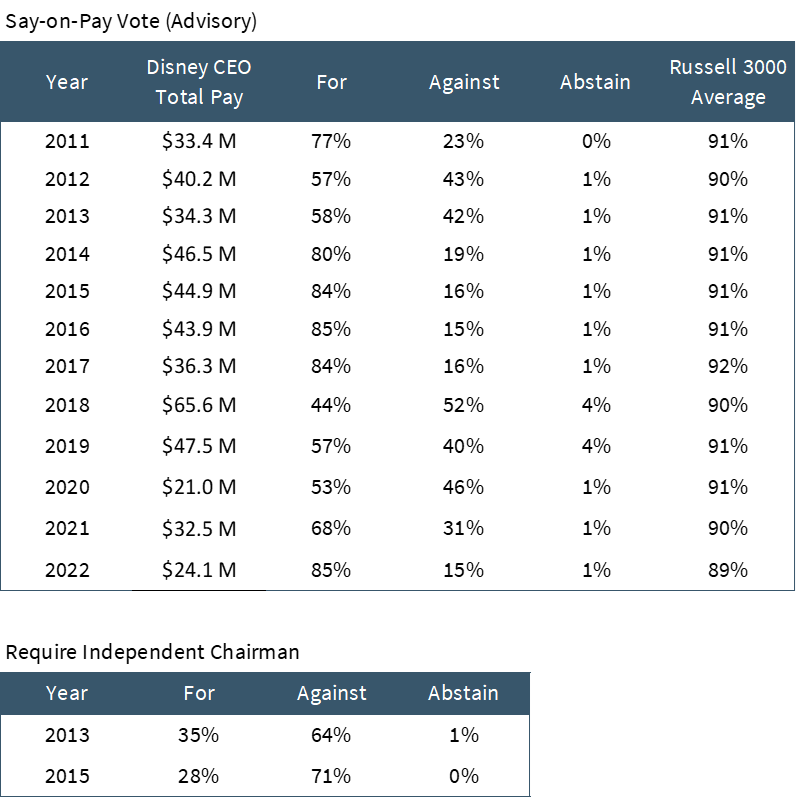

The next year, pension officials in Connecticut sponsored a proxy proposal to undo the combination. The proposal failed, receiving 35 percent support. Two years later, an individual investor filed a similar proposal, which received 28 percent support. Simultaneous with these efforts, Disney and Iger came under pressure over CEO pay practices. For many years, Iger received say-on-pay support well below average (see Exhibit 2).

In 2013, Disney extended Iger’s contract by 15 months, through June 2016. In 2014, Disney extended it again, to June 2018.

Naming and Un-Naming a Successor

In 2015, Disney announced that Tom Staggs would assume the role of chief operating officer, putting him in position to succeed Iger as CEO in 2018. “Tom is an incredibly experienced, talented and versatile executive,” Iger said in a statement. In conjunction with the move, Bob Chapek was promoted to replace Staggs as head of parks. CFO Jay Rasulo retired, and Christine McCarthy—Disney treasurer—became chief financial officer.

Experts applauded Stagg’s promotion. “He’s a lifer at Disney and understands the culture,” said one Wall Street analyst. “Bob [Iger] has a level of presence and charm that’s very hard to match, but of anyone at the company, Tom comes the closest,” said a former executive. “At Disney, the culture is you’ve got to know people, and Tom is gifted at that. Tom is the kind of guy who always asks how you’re doing in an elevator, never forgets your name once he meets you, and takes the time to learn about your kids,” said another former employee. “He’s like a clone of Bob.”

“The ability to exit gracefully while anointing a strong successor is one of the most important but least appreciated qualities of leadership,” observed one governance expert. “You have to admire Iger, who recognized that he’s done what he came to do and it’s time for new blood. From the outside, this appears to be going very smoothly.”

Almost as soon as the arrangement was put in place, however, it was undone. Just one year later, the company announced Staggs would leave the company, and the board would expand its search for Iger’s successor. Reports of what happened were not clear. Some suggested board members were not convinced Staggs had the skills to lead Disney’s creative effort. Others that Iger had developed reservations and dropped his backing.

No one knew what to make of the situation: Disney “went through a process that seemed very sensible and effective,” observed one expert. “Within a year, it has all unraveled. That’s a nightmare scenario for the board and the company.” An analyst wrote, “Mr. Iger is universally acknowledged as having provided exemplary leadership. How do you follow an act like that? Who could possibly live up?” “The best successor to Bob Iger may very well be Bob Iger.”

Many agreed: “Mr. Iger is now indispensable at Disney.”

Iger denied Staggs’ departure would delay his retirement, but it did. When Disney extended Iger’s contract to July 2019, he told investors, “I’m serious this time around…. I promise.” Six months later, Disney announced the planned acquisition of 21st Century Fox for $71 billion; in conjunction with the deal, Iger would stay on through the end of 2021 to complete the integration. He would also receive a one-time stock award valued at $142 million. When put before shareholders at the annual meeting, the proposed compensation plan was rejected by 52 percent of voters.

Naming and Un-Naming Another Successor

In February 2020, Disney found its new CEO: Bob Chapek, who had replaced Staggs as head of parks a few years prior. Iger would assume a newly created post of executive chairman and oversee creative activities until stepping down in December 2021. The leadership structure would give Chapek, who had limited experience with creative, time to learn that side of the business before assuming responsibility for all of Disney.

“I have absolute confidence in his abilities, as does the board,” Iger said. “I intend to work very closely with Bob. My goal when I leave here is that he will be just as steeped in the creative part of the business as I am today.”

The announcement was a surprise (“No one knew this was coming,” said one senior executive) but viewed positively. “Chapek is a really good, no-brainer pick,” commented one analyst. “He’s a really nice person who is part of the culture.”

Chapek promised continuity: “’I share his [Iger’s] commitment to creative excellence, technological innovation and international expansion, and I will continue to embrace these same strategic pillars going forward,” Chapek said.

Unlike Staggs, Chapek was not a “clone” of his former boss, instead described as disciplined, results-oriented, and preferring to stay out of the spotlight.

Although temporarily disrupted by the onset of Covid one month later, the transition appeared to work. Iger stepped down in December 2021, and independent board member Susan Arnold (former Procter & Gamble executive) became board chair. In June 2022, the board extended Chapek’s contract through 2024.

Just as suddenly as he was promoted, however, Chapek was dismissed. Two years into his tenure, in November 2022, Disney announced Chapek would step down and Iger return as CEO: “The board has concluded that as Disney embarks on an increasingly complex period of industry transformation, Bob Iger is uniquely situated to lead the company through this pivotal period. … We thank Bob Chapek for his service to Disney over his long career.”

While the immediate cause for Chapek’s dismissal was higher-than-expected losses in the company’s streaming division and a sharp drop in share price following the company’s fourth-quarter earnings, the full story was more complicated.

With the passing of time, it became clear that executives, unhappy with some of the structural and strategic decisions made by Chapek, complained both to the board and to Iger about the direction the company was taking. CFO McCarthy expressed to the board a lack of confidence in Chapek. She also communicated concerns directly to Iger, even though he was no longer at the company. One particular point of contention was Chapek’s decision to centralize decision making around the distribution of the creative content, with which Iger himself disagreed. Iger reportedly told one person, “He’s killing the soul of the company.” News reports such as this and others painted the picture of a CEO who had not fully disengaged from Disney, despite departing a year before.

The public did not know what to make of the situation. One investor was wary: “From a governance perspective it’s a big red flag.” The market, however, cheered Iger’s return, sending the stock up 6 percent on the day. In the words of one analyst, “Maybe the old hand on the tiller is what’s required.”

Iger expected his appointment to be temporary: “My plan is to stay here for two years. That’s what my contract says, that was my agreement with the board, and that is my preference.” The timeline did not work out that way. With the company—so successful just a few years before—facing challenges in almost every division, Disney extended Iger’s contract for two more years, through the end of 2026—marking over 20 years since first landing the job.

When asked later whether he would stay beyond 2026, Iger flatly said no. “I’m definitely going to step down. We are aggressively pursuing succession.”

Why This Matters

- The case of Disney illustrates the difficulty of replacing a highly successful CEO. Despite years of stellar performance and a long runway to evaluate talent, the Disney board was repeatedly unable to name a successor for Iger. Why? Was the process that the board used fundamentally flawed, or was the board not fully committed to replacing him? Did Disney lack for internal talent, or did the board (rightly or wrongly) simply not have faith in the talent it had? Was the board in control of the succession process, or was Iger?

- Twice Disney name a successor to Iger, and twice it subsequently changed course. Was the loss of confidence in these two executives well-founded? Or was it simply the case of not “measuring up” to their predecessor? Could either have succeeded with more careful grooming, development, and support from the board?

- Staggs was described as Iger’s clone, while Chapek his opposite. When is it better for a company to select a successor who carries forward the strengths of a predecessor, and when is it better to promote someone different? What risks does a board face in comparing candidates—in terms of vision, leadership style, and personality—to the outgoing CEO?

- Both Eisner and Iger were highly successful, long-tenured CEOs. At the same time, both men showed signs of heavy involvement in selecting their successors. How much influence should the outgoing CEO have in this decision? Should a highly successful CEO be given greater voice, because of the strength of their leadership; or is the opposite the case, that a board should exert greater control of the decision to ensure it is impartially directed? Are boards overly deferential to highly successful CEOs? If so, how can they maintain control of the process, while still leveraging the expertise, insight, and judgment this individual can provide? How can they tell when the outgoing CEO is stepping over the line and interfering?

- For years, Iger received very low say-on-pay results for the large compensation he received. And yet, the challenge of finding his successor demonstrates how difficult it was for Disney to replace him. Just how difficult is the job of CEO of Disney? What about the job to a typical multinational corporation? Is CEO talent rare—and therefore high CEO compensation justified—or do governance breakdowns impede the proper functioning of the CEO labor market and inflate pay? How many people can step into this job and perform exceptionally well?

- Research on the performance of CEOs who return for a second stint running the company (“boomerang CEOs”) is not especially favorable. Under what circumstances is it the right decision to bring back a former CEO? Was Disney right to bring back Iger?

Link to SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4655361.

Exhibit 1: Disney Stock Price History

1. Iger becomes CEO of Disney

2. Disney acquires Pixar

3. Disney acquires Marvel

4. Disney acquires Lucas Film

5. Disney names Staggs COO

6. Staggs resigns as COO

7. Disney acquires 21st Century Fox

8. Chapek becomes CEO

9. COVID-19 outbreak

10. Chapek resigns as CEO; Iger returns

Source: Stock price information from Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and Yahoo! Finance.

Exhibit 2: Disney Shareholder Voting Results, Selected Proposals

Source: ISS ESG Voting, Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS).

Print

Print