Caio de Oliveira is the Team Leader for Sustainable Finance, and Adriana De La Cruz and Pietrangelo De Biase are Policy Analysts in the Capital Markets and Financial Institutions Division within the Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This post is based on their OECD memorandum.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has recently published the first edition of the Global Debt Report, which examines sovereign and corporate bond markets, providing comprehensive and easy-to-understand data analysis into current market conditions and trends. This post builds on the analysis in the report’s third chapter on sustainable bonds, proposing questions policy makers and regulators may want to reflect on globally.

Sustainable bonds can be classified into two major categories. “Use of proceeds bonds” are bonds whose proceeds should be used to either partially or fully finance new or re-finance concluded eligible green, social or sustainable projects. “Sustainability-linked bonds” (SLBs) are bonds for which the issuer’s financing costs or other characteristics of the bond can vary depending on whether the issuer meets specific sustainability performance targets within a timeline but whose proceeds do not need to be invested in projects with an expected positive environmental or social impact.

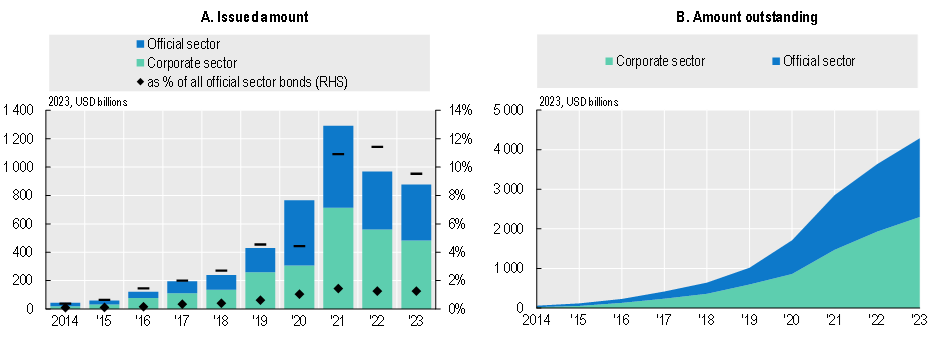

The sustainable bond market has grown substantially since its emergence in the last decade. At the end of 2023, the outstanding amount of sustainable bonds issued by the corporate and the official sectors totalled USD 2.3 trillion and USD 2.0 trillion (the latter category includes national and subnational governments and their agencies, as well as multilateral institutions). The total amount issued through sustainable bonds in the corporate and official sectors was six and seven times larger in the 2019-23 period than in 2014-18, respectively.

Global sustainable bond issuance and amount outstanding

Note: US municipal sustainable bonds are not included in the analysis.

Note: US municipal sustainable bonds are not included in the analysis.

Source: OECD (2024), Global Debt Report 2024: Bond Markets in a High-Debt Environment, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/91844ea2-en; LSEG.

The rapid growth of the sustainable bond market is a reason for optimism. If the proceeds of all sustainable bond issuances are invested in projects that deliver environmental and social benefits for relatively small costs, investors and society at large will profit. However, the regulatory frameworks and relevant institutions must guarantee that markets work efficiently and that investors’ interests are protected.

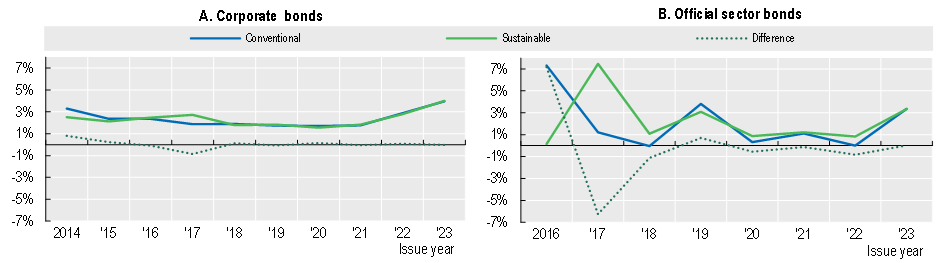

A key issue to consider is that there is no statistically significant evidence that companies systematically benefit from a premium for issuing a sustainable bond. Based on a limited sample of matched bonds, this also seems to hold true for the official sector.

Average difference in yield to maturity of conventional vs. sustainable bonds for matched corporates and official sector bonds

Source: OECD (2024), Global Debt Report 2024: Bond Markets in a High-Debt Environment, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/91844ea2-en; LSEG.

Source: OECD (2024), Global Debt Report 2024: Bond Markets in a High-Debt Environment, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/91844ea2-en; LSEG.

Investors may not be willing to pay a premium for sustainable bonds because either (i) many investors do not consider the sustainability-related impact of their investments or (ii), while investors may consider such impact, sustainable bond contracts might not create credible commitments from companies and official sector entities. It may also be the case that investors would be willing to pay a small premium for some sustainable bonds, but liquidity-related discounts (i.e., the expectation that the sustainable bond market will be less liquid than the conventional bond market) and the transaction costs involved in the investment process (e.g., assessing whether a sustainability-linked bond’s performance targets are ambitious) may obliterate any value assigned to the commitments in a sustainable bond contract.

The following questions in bold, as well as the commentary that follows them, are suggested to guide the discussions by policy makers, regulators and academics with the purpose of safeguarding investor’s interests and further developing sustainable bond markets:

Institutional Investors

1. May stewardship codes provide specific recommendations for the investment in sustainable bonds including, for instance, the importance of analysing whether SLBs’ performance targets are ambitious? SLBs are a promising tool for aligning investors’ sustainability-related preferences with investee companies’ impact on the environment and society. However, an SLB with an unambitious target functions de facto as a conventional bond because it does not change the decision-making process of the issuer’s leadership. A second party opinion provider may hardly be able to assess whether a sustainability performance target is ambitious or not. The decision is not only technically challenging, but also material for the issuance, and, therefore, institutional investors may need to have their own assessment.

2. Should central banks without any sustainability-related goal in their mandate buy sustainable bonds in their asset purchase programmes and for foreign reserve management? The slightly lower liquidity of sustainable bonds compared to similar conventional bonds may explain why most central banks tend to acquire only conventional bonds in their asset purchase programmes and foreign reserve management. The small importance of sovereign sustainable bonds in the market of all sovereign bonds may be another reason, especially considering the scale at which central banks operate. Nevertheless, if central banks’ asset purchase programmes are re-introduced in the future, there may be a case for them to fulfil their mandate also by acquiring sustainable bonds from large issuances with low credit risk. Simply excluding the possibility of acquiring sustainable bonds due to generally slightly lower liquidity may reduce the potential diversification of central banks’ portfolios.

Issuers

3. Is permitting GSS bonds’ proceeds to be used to re-finance concluded projects a good practice? The International Capital Market Association Use of Proceeds Principles explicitly admits the use of proceeds to re-finance existing or concluded projects, and most GSS bonds do indeed allow such a practice. This allows a difference between the capital raised through GSS bond issuances and the amount the issuer invests in new eligible projects. This may not be evident to many investors, and it clearly reduces the potential of the sustainable bond market to improve the environmental and social impact of companies and official sector entities. A possible way to mitigate this issue could be to mandate the issuers to disclose the planned allocation of proceeds between financing and re financing of eligible projects in the offering documents.

4. May the absence of contractual penalties for the failure to invest GSS proceeds in eligible projects limit the development of sustainable bonds markets? In a sample of 70 GSS bonds, no prospectus refers to a contractual penalty in case the issuer does not use all proceeds to finance or re finance eligible projects. Of course, this does not mean that issuers can simply disregard their obligation to use the proceeds of the issuance according to what is defined in the bond contract. Moreover, while symptomatic of their lack of importance for market participants, some prospectuses may have not included penalties that are indeed established in the bond contract. However, leaving as the only recourse to investors filing a lawsuit for a damages award may not offer them enough safety in some jurisdictions, especially because the effective damage may be difficult to assess in such a case. The lack of contractual penalties together with the explicit recognition in some prospectuses that non-compliance with the use of proceeds’ obligation does not constitute defaulting may give rise to moral hazard that might not be sufficiently addressed by the threat of a lawsuit for damages. Explicit contractual penalties may provide a stronger incentive for issuers not to deviate from their stated intent to invest in sustainable projects and reduce the risk of greenwashing.

Service providers and contracts

5. Should second party opinion providers, as well as providers of assurance on the performance of key performance indicators in SLBs, be regulated in a way similar to external auditors and credit rating agencies? A second party opinion is an assessment on whether the bond contract is aligned with a specific sustainable bond standard – the most common are the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Principles – and/or a taxonomy for sustainable activities. The same conflicts of interest that exist for external auditors and credit rating agencies are also present for providers of second party opinion and other forms of assurance for sustainable bonds. The bond issuers may hire these service providers for several sustainable bond issuances, but they provide a service that is relevant to the public interest. While most external auditors and some credit rating agencies are regulated and supervised in many jurisdictions, providers of second party opinion and other forms of assurance for sustainable bonds do not typically face the same scrutiny.

6. Would it be important to further investigate the governance and funding structure of the two organisations responsible for setting the most often used sustainable bonds standards, as well as one of the most well-known taxonomies? Both the ICMA and the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) have mostly only European and North American institutions in their decision-making process, and, in the case of CBI, a large majority of them are institutional investors. With the rapid increase in the size of the sustainable bond market and its globalisation, the governance and funding structure of both organisations may need to be reviewed for an assessment of whether they are fit-for-purpose.

7. What is the best way to make sure regional and national taxonomies for sustainable activities are consistent with high quality and internationally recognised taxonomies that facilitate the comparability of GSS bonds issued by both companies and official sector entities in different markets? After a period of prevalence of the CBI Climate Bonds Taxonomy, some regional and national institutions have created new taxonomies for sustainable activities, which issuers may use in both the corporate and official sectors. This raises three concerns. First, comparability between sustainable bonds may be reduced if they follow meaningfully different taxonomies. Second, taxonomies focused on the activities of the corporate sector may not be easily used by official sector entities. Third, organised industry interests may be successful in securing the inclusion of their business activities in a national or regional taxonomy in a way that may not fully take account of scientific evidence and broader policy objectives. Initiatives to improve the interoperability and comparability of regional or national taxonomies, such as the one led by the International Platform on Sustainable Finance, should therefore be welcomed.

Market development and liquidity

8. Should central banks’ and debt management offices’ lending facilities make sustainable bonds with high credit quality eligible to meet liquidity requirements and to the repo market in order to increase sustainable bond market liquidity? The liquidity of sustainable bonds tends to be slightly lower than for conventional bonds, which may hinder the further development of the sustainable bond market. Given that banks are active players in the repo market and that they tend to hold repo-eligible securities, allowing banks to hold high-quality sustainable bonds to meet liquidity requirements and making them repo-eligible in central banks’ and debt management offices’ lending facilities could help increase the liquidity of sustainable bonds and, thus, accelerate market development.

9. Should debt management offices issue sovereign sustainable bonds to facilitate the growth of a corporate sustainable bond market? There is limited evidence suggesting that sovereign issuance would support the long-term development of the corporate sustainable bond market. Additionally, in the absence of a premium for sustainable bonds, they would not offer cost incentives for sovereign issuers to issue them. However, sovereign issuers can still issue sustainable bonds if it aids in diversifying the investor base. Other reasons for issuing sustainable bonds fall outside the typical scope of debt management offices’ mandates, including aligning debt management activities with the government’s environmental and social policies.

Print

Print