Adam C. Pritchard is Frances & George Skestos Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School. This post is based on a working paper by Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati, Xuan Liu, and Professor Pritchard.

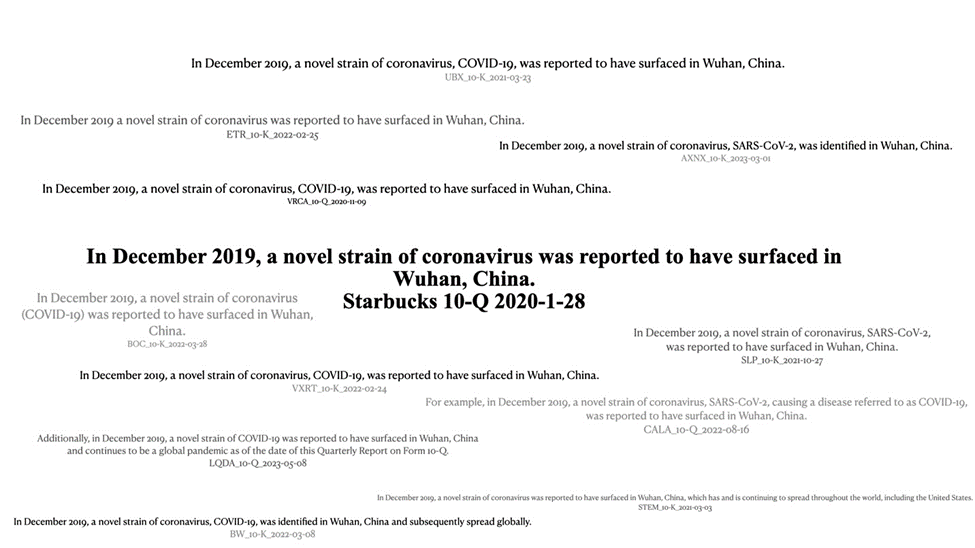

* This illustration depicts the widespread adoption of a boilerplate sentence concerning the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan by various firms in their 10-Ks and 10-Qs. The sentence originates with Starbucks’ January 2020 10-Q.

* This illustration depicts the widespread adoption of a boilerplate sentence concerning the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan by various firms in their 10-Ks and 10-Qs. The sentence originates with Starbucks’ January 2020 10-Q.

The SEC mandates that public companies assess new information that changes the risks that they face and disclose these if there has been a “material” change. But does this theory work in practice? Or are companies merely copying and repeating the same generic disclosures?

The term “boilerplate,” though widely used, is rarely defined with precision. In the context of risk factor disclosures, we take it to mean a high degree of similarity to what other companies are saying. A related concept here, also commonly used in an imprecise way, is “stickiness.” We use the term to mean that the disclosure in question is not updated, despite changed circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a lens through which to examine boilerplate and stickiness in risk disclosures. The pandemic disrupted business along with the rest of society, escalating uncertainty across various industries due to its severity and pervasiveness. Companies worldwide found themselves grappling with a uniform set of challenges, including stagnation in production due to quarantine measures, reductions in consumption, disrupted supply chains, and the looming threat of economic downturn. This unique context raises several questions: How did public companies adjust their disclosure strategies in response to the pandemic? More specifically, in terms of boilerplate and stickiness, which firms moved first to disclose COVID-19 risks? What was the pattern of subsequent disclosures? Did firms copy their COVID-19 risk factor disclosures from others, or did they craft their own tailored disclosures? And finally, as the COVID-19 risk dissipated, who updated their disclosures to reflect diminishing COVID-19 risks?

Our paper presents the results of an analysis focused on COVID-19 risk factor disclosures. We use a corpus comprising 3000 firms featured in the 2019 Russell 3000 Index. For each company, we track COVID-19 risk factor disclosures in quarterly Form 10-Qs and annual Form 10-Ks. We follow disclosures from January 2020, when the first public company made a COVID-19 risk factor disclosure, through the end of 2023. This timespan allows an exploration of the evolving narratives in risk factor disclosures and serves to capture a panoramic view of corporate responses through different phases of the pandemic.

We focus on three resource and risk-related factors likely to influence company disclosure strategy in response to COVID-19:

- Market capitalization;

- Litigation risk; and

- Insolvency risk.

Market capitalization reflects the fixed costs of disclosure, which may disproportionately affect smaller companies with fewer lawyers in-house devoted to preparing firm specific disclosures. Smaller companies with fewer resources, therefore, may be more inclined to wait to copy disclosure templates from their bigger counterparts. The second factor, litigation risk, is driven by the safe harbor from liability afforded by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act for companies that disclose significant risks that may affect their future performance. Companies at greater risk of class action litigation have more incentive to avail themselves of this protection. Insolvency risk helps examine our conjecture that companies in financial straits may reduce expenditures on disclosure.

We find that in 2020, the average boilerplate of COVID risk disclosure was 25.17%, in 2021 it rose to 49.73%, in 2022 it slightly decreased to 49.58%, and stood at 43.74% in 2023. In other words, there was a high degree of copying.

Upon further analysis, we find that larger companies and companies more vulnerable to securities class actions initially acted faster in providing pandemic-related risk disclosures. Copying began soon after industry leaders produced initial disclosure templates. From there, larger companies and companies with higher litigation risk were less inclined to copy from industry leaders during the early period of the pandemic in 2021. Put differently, companies with fewer resources (e.g., smaller legal teams perhaps), copied more as did those for whom making quality disclosures was less important (to protect from litigation). At the back end of the pandemic, larger companies were also more inclined to change their disclosures as the pandemic waned into 2023, while companies at risk of insolvency were less inclined.

Looking at the volume of COVID-19 risk factors, larger companies and higher litigation risk companies put out more words in 2020 and continued on the same path in 2021. These groups saw steeper declines in their number of words as the pandemic receded in 2023. Turning to sentiment, we see no pattern for our variables of interest at the outset of the pandemic, but larger firms showed a greater improvement in sentiment from 2021 to 2023. These results are consistent with resources and concerns about litigation risk mattering, separate from the SEC’s ideal of materiality, for disclosure outcomes.

As a test of whether factors directly related to the needs of investors also matter, we separately examine whether companies with business exposure to China (termed “China Exposure”) adopted different COVID-19 disclosure practices. We find that China Exposure corresponds to earlier and more responsive COVID-19 risk factor disclosures. This suggests that the behavior of these companies in disclosing risks is influenced, at least partially, by the considerations and requirements of reasonable investors.

Real world disclosure practices of public companies are a far cry from the SEC’s model of individualized disclosure of “material” risks. Instead, we find evidence, across a range of measures, of “follow the leader” copying of initial disclosures that results in a considerable amount of boilerplate. And that boilerplate is then slow to change, even as the underlying facts evolve. These latter findings fit better in a model where companies, concerned about the costs of disclosure, opt for individualized disclosure only when there are benefits to them beyond satisfying the SEC’s general mandates.

These patterns suggest a potential limitation on the SEC’s ability to mandate disclosures that will provide meaningful information to investors. Companies tend to respond to mandates when they are initiated, or if there is a shock to their business environment that clearly calls for a response, as the COVD pandemic surely did. But they quickly revert to a pattern of imitation, adopting a “copying mode” for their disclosures. If the SEC aims for disclosures that are specifically tailored to a company’s particular circumstances, or that adapt to changing conditions, some new strategies might be required.

The full paper is available here.

Print

Print