David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Lucia Song is a Research Analyst and Courtney Yu is Director of Research at Equilar Inc. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Larcker, Ms. Song, Mr. Yu, Amit Batish, and Brian Tayan.

When “say on pay” was legislated in the U.S. under the Dodd Frank Act of 2010, many observers hoped an advisory vote on executive compensation would provide a catalyst to “reign in” CEO pay that was perceived to be out of control. Nearly a decade and a half later, the perception of what say on pay can accomplish has changed significantly, in large part because of the unexpectedly high support pay packages usually receive. Over the last 14 years, companies in the Russell 3000 Index received average support of 91 percent for their pay programs. Moreover, average support has proven remarkably stable, fluctuating narrowly between a low of 89.2 percent (in 2022) and a high of 91.7 percent (in 2017). Meanwhile, the annual failure rate (companies receiving less than 50 support) averaged a mere 2 percent (see Exhibit 1). These results are hardly indicative of widespread displeasure among shareholders.

Nevertheless, for the subset of companies that do fail say on pay, the process brings scrutiny and pressure on the board of directors to respond. According to a recent report by Equilar, companies that receive less than 50 percent approval for say on pay make a variety of changes to plan design and disclosure (2.5 changes, on average, and in many cases more) in an effort to win greater shareholder support the subsequent year.

While we expect these changes bring pay packages more in line with shareholder preferences, no doubt they also reflect the preferences of proxy advisory firms. Proxy advisors are independent third-party companies that provide voting recommendations to institutional investors for proxy matters, including say on pay. Research has shown that the two largest proxy advisory firms (Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis) exhibit significant influence over voting outcomes. For example, Malenko and Shen (2016) estimate a negative recommendation from ISS leads to a 25-percentage point reduction in voting support for say-on-pay proposals. As such, their determination of the quality of a company’s compensation program influences to a high degree whether that company receives high or low support.

Still, the actions companies take in response to a failed say-on-pay vote have received remarkably little attention. How do companies “course correct” after a failed vote? Do they primarily reduce pay levels, or do they make ancillary changes to plan design (performance targets, measurement periods, and mix) without committing to a lower overall level? Are these changes substantive (i.e., lead to a closer alignment between pay and performance), and do shareholders subsequently approve of them?

In this Closer Look, we take a deep dive into data collected by Equilar on a sample of the 77 companies in the Russell 3000 Index that failed (obtaining less than 50 percent of the vote) their say-on-pay votes in 2022 and the changes they implemented in 2023.

Response to Failed Say on Pay

The 77 companies that failed their say-on-pay vote in 2022 are highly diverse in terms of revenue, market capitalization, and prominence. They had average sales of $8 billion (median $1.2 billion), ranging from a low of zero to a high of $131 billion. Similarly, the average market capitalization was $23.5 billion (median $2.5 million) and ranged from a low of $213 million to a high of $468 billion. They include highly recognized name brands (such as J.P. Morgan, Netflix, and Harley Davidson) and relatively unknown ones (such as UroGen Pharma, OSI Systems, and 2U Inc.).

Shareholders rejected the pay packages of these companies quite convincingly. Average support was only 35 percent.

Average CEO compensation in our sample was $23.1 million (median $16.8 million) the year these pay plans were rejected. While a fair comparison would measure each CEO’s pay against that of a comparably sized peer in the same industry, a rough comparison to the Russell 3000 (median CEO pay $6.2 million) shows the pay levels in our sample are high. They are also high relative to what the same CEOs received the previous year, when average pay was $14.2 million (median $6.7 million). It seems likely that high pay levels were a main determinant of the voting results.

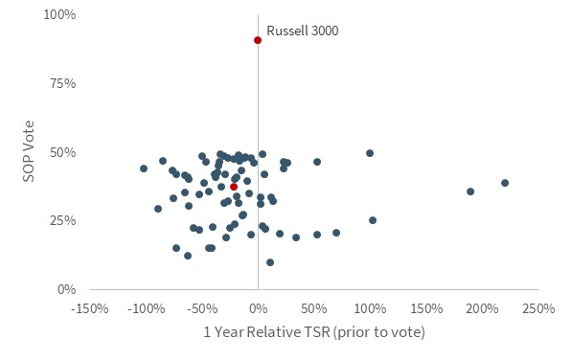

Stock-price performance seems also to modestly contribute to voting outcomes. In a year when the Russell 3000 increased by 26 percent, the companies whose pay plans were rejected had a total shareholder return of only 4 percent. While most companies (71 percent) underperformed the Russell 3000 Index in the year leading up to the vote, it is perhaps surprising that 29 percent outperformed (see Exhibit 2).

Almost every company in the sample experienced a significant decline in say-on-pay support relative to the previous year, when average support was 77 percent (median 83 percent). However, even these “pre-rejection” levels are noticeably below the Russell 3000 average of 90 percent, suggesting shareholder discontent with the pay practices of these companies is somewhat long-held (see Exhibit 3).

Proxy advisory firms also appear to play a role in shareholder decisions to reject compensation, consistent with the scientific evidence cited earlier. In 2021 (the year prior to our year of focus), 42 companies received a positive recommendation from ISS and average shareholder support of 88 percent for their pay programs, whereas 20 received a negative recommendation and garnered average support of only 53 percent—a 35 percent differential. In 2022 (the year of our focus), ISS recommended against all of these firms but one, and average support fell to 36 percent.

Among the firms where ISS changed its vote recommendation from positive to negative, say-on-pay support fell an average of 54 percentage points year over year, compared with only a 15 percent reduction in support when ISS maintained a negative recommendation both years (see Exhibit 4).

Reason for “No” Vote and Company Response

Consistent with the scientific research, companies that fail their-say-on-pay vote engage in outreach and increase disclosure in an effort to improve reputation and relation with shareholders. 68 of the 77 companies in our sample describe in the annual proxy the following year their efforts to engage shareholders. Disclosure usually includes the following: First, they describe shareholder outreach, including the number of institutional investors contacted, the percent ownership of these shareholders, and the board members or executives who participated in these meetings. They often also mention outreach to proxy advisory firms. Then, they summarize the feedback received from shareholders, often in tabular format, and describe the changes made in response to each area of concern (see Exhibit 5 for an example).

Through this disclosure, we gain some insight into the primary factors that drove a negative say-on-pay vote. 30 percent of the companies cited criticism of a special award (its size, term, or performance criteria for vesting equity grants) as the main reason for the negative vote. 18 percent cited too little (or no) performance-based awards in the long-term incentive program. 13 percent said their shareholders believe the overall pay level was too high. 12 percent objected to the performance metrics used in the short-term bonus. 10 percent criticized a discretionary action the company took to award a bonus payment (short- or long-term) when it would not otherwise have been merited. Less frequently, the primary objection was pay mix, disclosure practices, the choice of companies in the peer group, or governance practices (apart from its compensation structure—see Exhibit 6).

In response to this feedback, companies made 2.5 changes, on average, to their compensation program. Most frequently, companies made changes to the performance metrics or weightings in their short- or long-term incentive programs (66 percent of companies). 36 percent increased disclosure. Other modifications include a change in performance measurement period (19 percent), a reduction in overall pay (18 percent), the addition or strengthening of clawbacks (16 percent), and a shift away from time-based awards toward performance equity (16 percent). Actions less frequently made include compensation caps, modifying peer groups, ownership guidelines, ESG incentives, eliminating overlapping metrics, or changes to the compensation consultant or compensation committee members. 5 percent of companies committed not to awarding special awards in the future (see Exhibit 7).

Impact of Changes

The companies in our sample experienced a significant improvement in their say-on-pay voting outcomes after making these changes. Average support increased from 35 percent to 76 percent (and median support increased from 37 percent to 85 percent). That is, say on pay rebounded to the levels achieved prior to the failed vote but remained notably below Russell 3000 average support (90 percent).

Average compensation fell from $23.1 million to $11.8 million (median from $16.8 million to $10.4 million), primarily due to a reduction in long-term equity awards. Still, these pay levels are well above Russell 3000 averages ($6.2 million). Measuring compensation the year after the failed vote with compensation the year before the failed vote, we see median pay still increased over 50 percent ($10.4 versus $6.7 million). Despite a strong rebuke from shareholders and making significant changes to pay structure and disclosure, companies overall did not substantially reduce pay (see Exhibit 8).

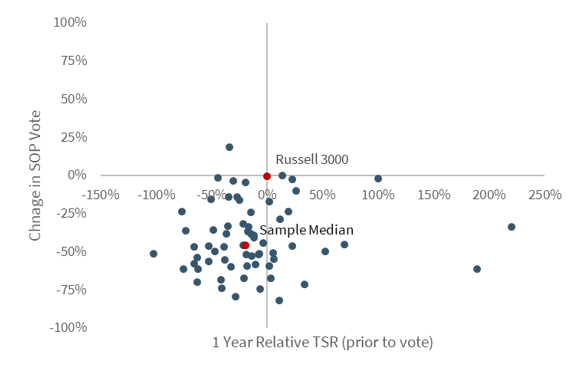

Furthermore, the rebound in say-on-say support was not a result of impressive total stockholder returns. Median returns were negative 18 percent—barely distinguishable from the median return of the Russell 3000 which was negative 19 percent (see Exhibit 9).

Shareholder support for compensation programs was somewhat correlated to the number of changes the company made to its pay plans. Companies that made 2 or 3 changes to their program realized larger increases in say on pay compared to companies that made no changes or 1 change. Companies see diminishing returns beyond 4 changes (see Exhibit 10).

A clear pattern emerges when we separate companies based on whether or not they were able to win a positive recommendation from ISS because of these changes. Companies whose changes met the approval of ISS almost uniformly experienced larger say-on-pay increases than those who did not—without regard to the number of changes made. The number of changes did not matter nearly so much as whether these changes were in line with ISS criteria (see Exhibit 11).

This finding is consistent with recent scientific research showing that proxy advisory firm recommendations contribute to standardization in CEO compensation. For example, studies by Jochem, Ormazabal, and Rajamani (2021) and Cabezon (2024) find that proxy advisor influence is a factor in the standardization of CEO compensation within industry and size groups and across pay components. Whether standardization is good or bad for shareholders is not yet known; however, both of these studies find negative associations.

Why This Matters

- Companies that fail say on pay are subjected to additional scrutiny from shareholders and proxy advisory firms, compelling them to defend their choices and make changes to gain support in subsequent years. Does this process reflect a healthy dynamic of the market correcting egregious practices, or does it simply reflect a standardization process whereby observed outlier practices are brought in line with industry norms? Do the changes companies make in response to a failed vote lead to substantive improvement in the managerial incentives of their pay programs?

- In our sample, the leading factor triggering a failed say-on-pay vote was a decision to grant a large one-time special award to the CEO. Why do companies make these grants, when doing so clearly draws the attention of shareholders and proxy advisory firms? Are there situations when such an award might be better warranted (i.e., when the company is investing in an important but highly risky long-term initiative), and others when it might be less so (i.e., to replace previously granted awards that are underwater)? Do shareholders distinguish between these two situations through say on pay?

- It is very difficult for third-party researchers to understand and digest the pay structure and issues regarding pay among even a relatively small sample of companies. How can a portfolio manager analyze pay across an entire portfolio and make informed decisions? In theory, proxy advisory firms serve this market need. However, it is also not clear that proxy advisory firms can digest and analyze this information. How effective are proxy advisory firms at identifying companies with “inappropriate” pay practices? Are the companies that fail their say-on-pay votes the most egregious offenders, or “unfairly” caught up in somewhat arbitrary compensation guidelines?

- Despite the additional scrutiny that companies receive for failing say on pay, very few reduce pay in a meaningful way in comparison to what they paid the year prior to the failed vote. How substantive are the changes a company makes following a failed vote? Do they represent an honest effort by compensation committees to improve poorly structured incentives, or are they cosmetic moves to appease shareholders and proxy advisory firms?

- Is there any evidence that say on pay or proxy advisor recommendations on say on pay create better managerial incentives and increased shareholder value?

Link to SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4982752.

![]() Exhibit 1: Long-Term Voting Trends, Say on Pay

Exhibit 1: Long-Term Voting Trends, Say on Pay

Note: Sample includes companies in the Russell 3000 Index. 2024 data is year-to-date (as of September 2024).

Source: Semler Brossy, “2024 Say on Pay & Proxy Results,” September 26, 2024.

Exhibit 2: Say-on-Pay Vote as a Function of Total Shareholder Returns

Say-on-Pay (2022) and Absolute TSR

Say-on-Pay (2022) and Relative TSR

Note: AMC (stock return 1183 percent, say on pay 36 percent) not shown.

Source: Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 3: Change in Say on Pay as a Function of TSR

Change in Say-on-Pay (2022 vs. 2021) and Relative TSR

Three Year Say-on-Pay Results (Year Before, Year of, and Year Following)

Source: Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 4: Change in Say on Pay and Proxy Advisor Influence

Change in Say-on-Pay (2022 vs. 2021) and Change in Proxy Advisor Recommendation

ISS Recommendation and Say-on-Pay Vote

Source: Proxy voting recommendations from Jon Zytnick, “Imputing Proxy Advisor Recommendations,” Social Science Research Network (July 2024), available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4878758.

Exhibit 5: Example of Disclosure

Stockholder Responsiveness Summary

In response to the 66% of our stockholders voting against our 2022 say-on-pay, the Board undertook an extensive outreach effort to understand our stockholders’ concerns and make responsive changes to our executive compensation program which are summarized below. Our directors, including Jessica Blume, Christopher Coughlin, Wayne DeVeydt and Theodore Samuels participated in a number of these engagements.

We extended meeting invitations to 16 stockholders, representing approximately 56% of our outstanding shares, and ultimately met with 11 stockholders, representing approximately 41% of our outstanding shares.

In addition, members of our management team and Board regularly meet with stockholders and proxy advisor firms to gather their perspectives on key topics including our performance and strategy, corporate governance, management succession planning, executive compensation, human capital management and corporate responsibility.

Beyond our governance-focused engagement, our investor relations team and members of our senior management team regularly communicate with investors in connection with quarterly earnings calls, investor and industry conferences, analyst meetings and individual discussions with stockholders.

In response to the result of our 2022 say-on-pay vote, and our subsequent stockholder outreach, we have made some important changes to our compensation program starting with the 2023 short-term annual incentive plan and our 2023-2025 long-term incentive plan as summarized below.

Source: Centene, form DEF14A, filed with the SEC March 24, 2023.

Exhibit 6: Company Explanation for Failed Vote (Primary Reason)

Source: Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 7: Number and Type of Changes Made to Compensation Program

Number of Changes

Types of Changes

Source: Lucia Song, “How Companies React to Say on Pay Failures,” Equilar (May 1, 2024).

Exhibit 8: Two-Year Change in Say on Pay as a Function of Two-Year

Change in Pay Change in Say on Pay (2023 versus 2021) and Two-Year Change in Pay

Source: Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 9: Change in Say on Pay as a Function of Total Shareholder Returns

Change in Say on Pay (2023 versus 2022) as a Function of Absolute Total Shareholder Returns

Change in Say on Pay (2023 versus 2022) as a Function of Relative Total Shareholder Returns

Source: Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 10: Change in Say on Pay as a Function of Number of Changes to the Pay Program

Source: Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Exhibit 11: Change in Say on Pay and Change in Proxy Advisor Rating

Change in Say on Pay and Number of Changes, Sorted by ISS Rating

Source: Proxy voting recommendations from Jon Zytnick (2024). Data from Equilar; research by the authors.

Print

Print