Augustin Landier is a Professor of Finance at HEC Paris, Parinitha Sastry is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Columbia Business School, and David Thesmar is the Franco Modigliani Professor of Financial Economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management. This post is based on a recent article forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics, by Professor Landier, Professor Sastry, Professor Thesmar, and Professor Jean-Francois Bonnefon.

Over recent years, responsible asset management has developed considerably in size. However, the exact nature of responsible investors’ preferences remains somewhat elusive. Our paper investigates the moral preferences of investors through incentivized experiments.

There are essentially two main views of investors’ ethical preferences in the literature.

- Value-alignment refers to investors’ aversion to owning shares in companies whose business practices conflict with their own moral values. Such investors experience corporate externalities of the portfolio companies they own as a non-pecuniary dividend.

- Impact-seeking investors prioritize the social consequences of their investment choices, valuing the additionality of their actions. For these investors, corporate externalities impact their utilities regardless of their stock holdings, reflecting a preference for making a positive social impact.

Philosophically, value-alignment aligns with deontological ethics, where actions are judged based on adherence to rules, while impact-seeking corresponds with consequentialism, focusing on the outcomes of actions.

Understanding the distinction between these two preferences is crucial for designing financial products that appropriately cater to investors’ moral preferences. For instance, value-alignment investors may prefer to avoid investing in polluting companies that do not align with their values. However, impact-seeking investors may not value divestment if the action does not materially affect those companies, such as if they can secure financing from other sources. Impact-driven investors may prefer engaging with “dirty” companies to improve their practices rather than divesting entirely.

Experimental Design

Our experimental design seeks to disentangle these two types of altruistic preferences in a highly simplified setting. Using a simplified setting ensures that we can directly measure these preferences. We illustrate the conceptual underpinnings of our experiment with the following thought experiment involving a hypothetical company. Imagine a one-period setting where a company’s profit per share is worth $1. Now, assume the company is committed to spending 40% of its profit on charity donations and distributing the rest as a dividend to shareholders. Non-altruistic investors would be willing to pay up to $0.6, the amount they would directly receive as a dividend. However, if investors value the company’s prosocial behavior, the price P they are willing to pay might be at a level higher than $0.6. In this case, P-0.6 measures the component of valuation by the shareholders that reflects their moral preferences.

The key innovation of our experiment is to uncover what type of altruistic preference the investor has, impact-seeking or value-alignment. If an investor is impact-driven, P should be higher than $0.6 only if the donation depends crucially on them buying the stock—what we refer to as pivotality. Indeed, if the company’s donation is set to happen anyhow, her purchase of the stock will have no impact on the externality. Therefore, an impact-driven investor does not feel compelled to pay more than $0.6. In contrast, if investors exhibit value-alignment preferences, the investors valuation of P-0.6 will be the same even if their purchase of the stock has no impact on whether the externality occurs.

We can uncover investor moral preferences by comparing investors’ willingness to pay when corporate externalities either do or do not depend on them buying the stock that is auctioned. This allows us to tease apart value-alignment preferences from impact-seeking preferences.

We implement this insight in an online experiment that asks participants to bid on synthetic companies with randomly varying dividends as well as randomly varying prosocial behavior — some neutral (no externality), some generous (donating profits to charity), and some harmful (reducing charitable contributions). Participants were incentivized with real monetary stakes and underwent a practice quiz to ensure their understanding the auction bidding mechanism.

Key Findings

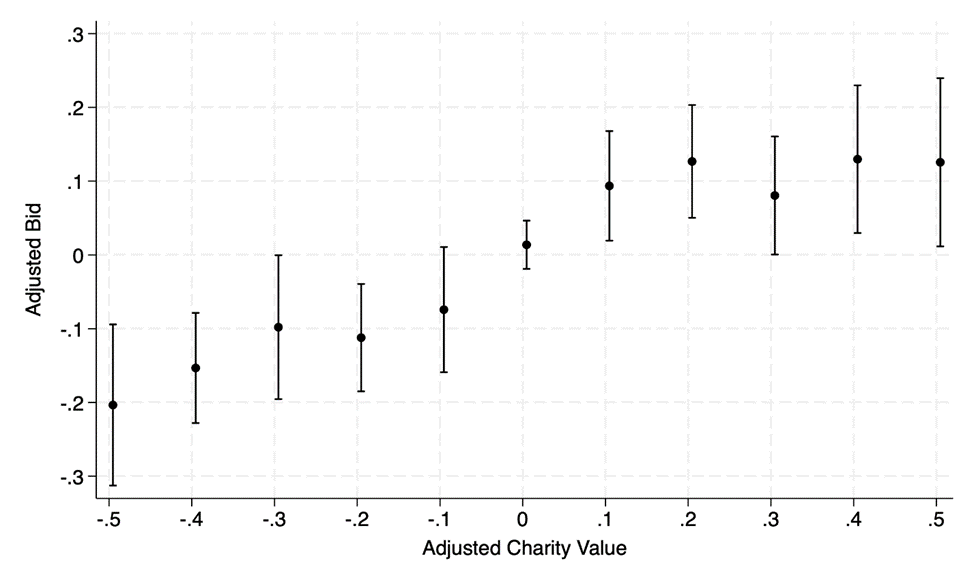

First, we find that investors are prosocial. In our main specification, participants value 61c each dollar given to, or taken from, charities by the firm. We also find that the scaling of non-pecuniary preferences is close to linear: doubling the size of a social externality doubles its impact on willingness to pay. These results can be seen in the figure below, where we plot the participants’ average willingness to pay for a given level of corporate externalities, after controlling for the direct dividend the participant would receive.

Second, investors’ willingness-to-pay for corporate externalities did not change when those corporate externalities were contingent on investors buying the stock. The figure below shows this result, since the relationship between bids and charity externalities was statistically indistinguishable regardless of whether the investor was pivotal or not.

This suggests that impact-seeking motives were negligible in this context, with value-alignment motives dominating.

Robustness Checks and Further Analysis

The study included a number of robustness checks and heterogeneity splits to assess whether variation in demographic characteristics like education or financial sophistication influenced results, or whether these results changed with larger stakes. Across a range of specifications, we found no statistically significant differences in bidding behavior or sensitivity to pivotality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the research highlights the predominance of value-alignment preferences among investors. The findings suggest that while investors value corporate externalities in their investment choices, this concern does not translate into preferences for impact. These findings provide insights into designing financial products that align with investors’ ethical considerations.

Print

Print