Lubos Pastor is the Charles P. McQuaid Professor of Finance and Robert King Steel Faculty Fellow at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Robert F. Stambaugh is the Miller Anderson and Sherrerd Professor of Finance and Professor of Economics at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and Lucian A. Taylor is the John B. Neff Professor in Finance at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This post is based on their recent paper.

Summary

We quantify the U.S. corporate sector’s carbon externality by computing the sector’s “carbon burden”—the present value of social costs of its future carbon emissions. Our baseline estimate of the carbon burden is 131% of total corporate equity value. Among individual firms, 77% have carbon burdens exceeding their market capitalizations, as do 13% of firms even with indirect emissions omitted. The 30 largest emitters account for all the decarbonization of U.S. corporations predicted by 2050. Predicted emission reductions, and even firms’ targets, fall short of the Paris Agreement. Firms’ emissions are predictable by past emissions, investment, climate score, and book-to-market.

Motivation

How big are corporate externalities? This question matters not just for policymakers but also for companies, investors, and consumers. It also has implications for the debate over the famous Friedman doctrine, which argues that companies should just maximize profits. The Friedman doctrine becomes controversial in the presence of externalities, especially if those externalities are large.

In this paper, we attempt to quantify one externality: damages from corporate emissions of greenhouse gases. This “carbon externality” is clearly important given the severity of the climate crisis. Key to measuring this externality is recognizing its future dimensions. First, emissions in any given period have climate consequences for many years. Second, emissions are expected to remain high for many years, and the future path of emissions will be crucial in determining climate change. Our contribution is to quantify the carbon externality while incorporating the impact of future emissions.

Introducing the carbon burden

To measure the magnitude of the carbon externality, we propose a metric that we refer to as the “carbon burden.” Consider an economic unit, such as a firm or a collection of firms, that emits carbon. We define its carbon burden as the present value of the social costs associated with its future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. We estimate the unit’s carbon burden in four steps:

- Forecast the unit’s GHG emissions in each future year t. We use emission forecasts at the aggregate, industry, and firm levels to compute carbon burdens at each of those levels. Our forecasts of aggregate U.S. carbon emissions come from U.S. government agencies. Our firm-level emission forecasts come from MSCI, a leading data provider, and we also aggregate those forecasts to the industry level.

- Multiply year t’s emissions forecast by the social cost of carbon (SCC) in year t. The SCC is the dollar cost of societal damages resulting from the emission of one additional ton of carbon into the atmosphere. We use the Environmental Protection Agency’s most recent SCC estimates.

- Discount the result of step 2 back to the present. The result is the present value of damages from emissions in future year t. We show results using a range of discount rates.

- Sum those present values across all future years t. This sum is the carbon burden.

The concept of carbon burden is similar in spirit to that of market value, in that both are present values of infinite streams of estimated future dollar values. A firm’s market value is the present value of its future dividends, whereas a firm’s carbon burden is the present value of the social costs from the firm’s future emissions. The two concepts measure different dimensions of a firm’s value to society, with market value belonging to shareholders and carbon burden representing a negative value borne by all. Both market value and carbon burden are measured in dollar terms, and we compare them in our analysis. Whereas market value is easily measured, our carbon burden estimates come with a fair amount of imprecision.

We equate aggregate corporate emissions with total U.S. emissions, because virtually all emissions are related to the emissions of some company, directly or indirectly. Of course, responsibility for corporate emissions does not rest solely with corporations. Households and politicians, for example, surely share this responsibility. We do not attempt to assign responsibility for the carbon externality.

The U.S. carbon burden

At the aggregate level, we analyze the total U.S. carbon burden as of year-end 2023. Applying our baseline 2% discount rate, we estimate the U.S. carbon burden to be $87 trillion, which is 131% of the total value of U.S. corporate equity. These large estimates highlight the severity of the climate crisis, and they suggest that continued debate over the Friedman doctrine is warranted.

After quantifying the aggregate U.S. carbon burden, we analyze its potential reductions stemming from the 2015 Paris Agreement, under which the U.S. aims to reduce its emissions by at least 26% by 2025 and 50% by 2030, relative to the 2005 level. We find that achieving the Paris goals would reduce the U.S. carbon burden substantially, by either 21% or 32%, depending on the projected emission path beyond 2030. We also show that achieving the Paris goals would require major emission reductions by the largest emitters. However, we find that the largest emitters’ reported emission targets are insufficient for the U.S. to meet its Paris goals, even if we take those targets at face value. Moreover, when we replace firms’ targets by emission forecasts from MSCI, the shortfall relative to Paris widens further.

Carbon burdens across industries

Carbon burdens differ greatly across industries. The ratios of carbon burden to market value are as high as 7 and 3 for the utilities and energy sectors, respectively, and as low as 0.01 for the financial and business equipment sectors. These estimates are based on direct (scope 1) emissions, which are emissions from sources owned by the firm. The numbers change little when we add scope 2 emissions, indirect emissions from the consumption of purchased energy, but adding scope 3 emissions, indirect emissions incurred in the firm’s entire value chain, matters more. Based on total (scope 1+2+3) emissions, the energy sector’s ratio of carbon burden to market value grows to 66, and the ratio exceeds 10 for four other sectors. One of these is financials, whose ratio of 17 for total emissions stands in stark contrast to the 0.01 ratio for direct emissions.

Thinking about the future is important for quantifying the carbon externality. To illustrate this point, we divide each industry’s carbon burden from all future years’ emissions by the industry’s burden from a single year’s emissions in 2023. This ratio ranges from 49 to 80 across sectors for direct emissions, and the range for total emissions is even broader. This wide dispersion reflects large differences in forecasted emission growth rates across sectors. For example, cumulative direct emission growth from 2023 to 2050 is –37% for utilities but –6% for financials, based on MSCI’s forecasts.

Carbon burdens across firms

At the firm level, we find high cross-sectional dispersion in the ratios of carbon burden to market value. For many firms, these ratios are small; for example, they are smaller than 0.05 for 55% of firms, based on direct emissions. However, for 13% of firms, these ratios are greater than one. For these firms, which represent 9% of total market capitalization, their carbon burdens exceed their market capitalization. Carbon burdens are even larger when we add indirect emissions. Based on total emissions, 77% of firms, which represent 50% of total market capitalization, have carbon burdens larger than their market capitalization.

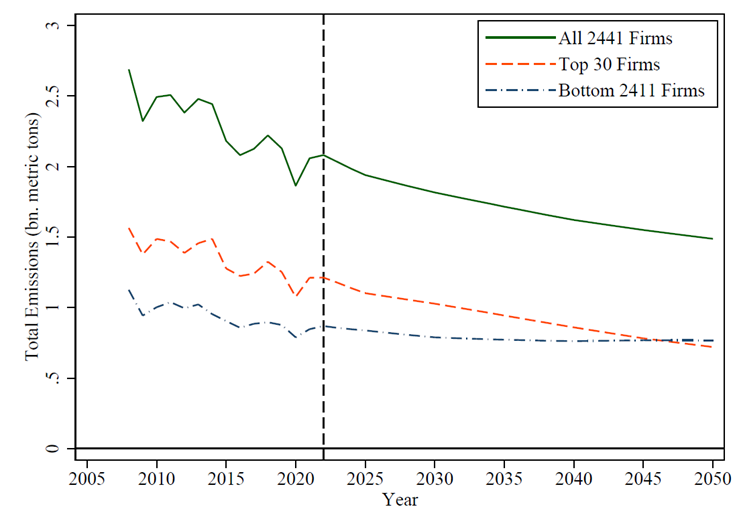

Dispersion in firms’ carbon burdens comes from dispersion in two inputs: firms’ current emissions and their growth rates. We find these two inputs are negatively related across firms. For example, for the top 5% of current emitters, their forecasted cumulative growth rate of direct emissions from 2023 to 2050 is ![]() 14%, but for the bottom 5% of emitters, it is +25%. This negative relation is so strong that the 30 largest emitters are expected to account for the entire drop in aggregate U.S. corporate emissions by year 2050, as we show below.

14%, but for the bottom 5% of emitters, it is +25%. This negative relation is so strong that the 30 largest emitters are expected to account for the entire drop in aggregate U.S. corporate emissions by year 2050, as we show below.

Past and future emissions

Besides current emissions, a few other firm characteristics, namely investment, climate score, and the book-to-market ratio, help explain the cross section of forecasted emission growth rates. Emissions are expected to grow faster for firms that invest more, firms with lower climate scores, and value firms, though these relations are not always significant.

Given its focus on future emissions, a firm’s carbon burden could potentially be used to measure the firm’s greenness. Suppose two firms have the same emissions today, but the first firm has a credible decarbonization plan whereas the second firm does not. The first firm’s carbon burden is then lower, making the firm greener. If firms’ carbon burdens were widely reported, they could incentivize firms to develop emission reduction strategies.

Print

Print