Marcel Kahan is the George T. Lowy Professor of Law at New York University School of Law, and Emiliano Catan is the Catherine A. Rein Professor of Law at New York University School of Law. This post is based on their recent paper.

Scholars have long debated how corporate governance affects firm value. The topics analyzed include, among many others, board composition, proxy access, poison pills, antitakeover statutes, staggered boards, hedge fund activism.

Confronted with conflicting arguments, scholars have turned to empirical evidence to resolve the theoretical debates. An approach that has become increasingly popular over the past few decades is to measure the effect of governance mechanisms on Tobin’s Q: the market value of a company divided the replacement cost of the company’s assets.

Q regressions come in two variants, cross-sectional and “within firm.” A typical within firm study uses a panel dataset involving many firms that become treated during the sample period to regress firm Q against a treatment indicator, a vector of firm indicators, a vector of time indicators, and possibly other control variables. This research design effectively compares the post-treatment changes in the Q of treated firms to contemporaneous changes in Q in firms for which treatment status has not changed during the same period. If the coefficient estimate for the treatment indicator is positive (or negative), this is taken as evidence that treatment enhanced (or reduced) firm value.

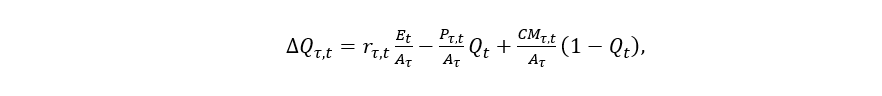

But this approach has numerous problems. Most fundamentally, there is no theoretical foundation for using changes in Q over the long term to evaluate the effect of treatment on firm value. In the very short term, treatments that affect stock prices have an immediate impact on the Q numerator and no other effects. Over time, however, factors other than returns also matter and the change in Q that a firm experiences in the period between t and τ>t, will equal

where rτ,t is the percentage total return, Et is the firm’s market value of equity, Aτ is the book value of the firm’s assets![]() Pτ,t is the dollar value of the realized profits, and CMτ,t is the net dollar value of the firm’s capital market transactions (dollars raised by issuing debt and equity minus dollars paid out in dividends, interest, principal payments, and stock repurchases).

Pτ,t is the dollar value of the realized profits, and CMτ,t is the net dollar value of the firm’s capital market transactions (dollars raised by issuing debt and equity minus dollars paid out in dividends, interest, principal payments, and stock repurchases).

Of these factors, the only one that meaningfully reflects the effect of treatment on firm value is returns. Looking at Q regressions from this perspective reveals three key points. First, it shows that ∆Q is a noisier measure than returns when what we are after is the effect of treatment on firm value. Empirically, over a multi-year period, returns explain only 20% to 30% of the variation in Q.

Second, equation (1) shows Q regressions will generate biased estimates if treatment affects (Pτ, t/ Aτ) or (CMτ,t / Aτ). This is not some trivial concern. Treatments that increase returns are very likely to increase profits at some point, and the respective effects on ∆Qτ,t will be in opposite directions. Whether the net effect on ∆Qτ,t is positive or negative largely depends on whether the marginal profits attributable to treatment are realized more slowly or faster than pre-treatment profits. As a theoretical matter, therefore, the effect of a treatment that raises firm value on ∆Qτ,t is indeterminate. In addition, corporate governance treatments can affect realized profits or capital market transactions without affecting firm value. For example, antitakeover provisions may plausibly affect the timing of profits (by making management pursue more projects with a short-term horizon) and capital market transactions (by inducing firms to return more value to shareholders through dividends or share repurchases) without materially changing firm value.

Third, to perform within-firm Q regressions, one must have a meaningful number of firms whose treatment status changes over the period of analysis as well as information about the share prices for these firms. That means one could—and should—instead directly study how that change in treatment status affected stock returns for those firms. Q regressions do not look at a different way to assess changes in firm value (such as changes in profitability) that, while less precise than returns, may pick up some facet of firm value than is not reflected in returns. Rather, they start with returns and then transform the return measure in a way that, at best, adds noise and, at worst, generates bias. Thus, just as one would not use a contaminated data set derived from a clean data set when the clean data set is available, one should never use Q regressions to evaluate treatment when returns are observable.

But what about cross-sectional Q regressions? These regressions regress Q levels of treated and untreated against a treatment indicator and various controls but do not include firm fixed effects because only one observation for each firm may be available or only a few firms may experience changes in treatment during the sample period. Given such data constraints, conducting a return study may not be feasible. Despite all their problems, may Q regressions be the best one can do and at least better than conducting no study at all?

Our answer is no. The reason harks back to where we started: Q regressions lack a proper theoretical foundation. While cross-sectional Q regressions do not explicitly measure the effect of treatment on firm value, they do compare treated and untreated firms. Cross-sectional Q regressions are thus based on two premises: first, that treated firms, after taking into account the various added control variables, would but for the treatment resemble untreated control firms; and second, that differences in Q are attributable to the effect of treatment on returns.

The second premise, in particular, becomes increasingly less tenable the longer the time over which any treatment is allowed produce its effects. Unlike “within-firm” studies, which often follow Q for up to three to five years after treatment took place, cross-sectional Q regressions compare the Q of firms that were treated at any prior point of time, even decades earlier, to the Q of untreated firms. But the longer the period between treatment and measurement of Q, the more likely it is that the effects of treatment on Q are due to the effects of treatment on profits or capital market transactions, rather than on returns.

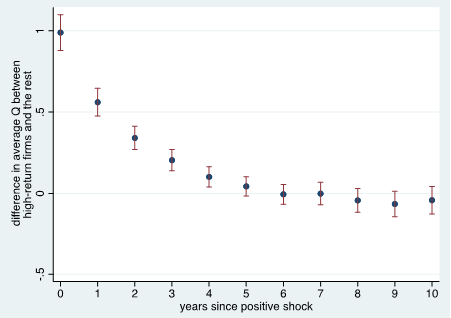

To provide a sense of how quickly the effects of a stock return shock on Q dissipate, we identified the 10% of U.S. publicly traded firms with the highest stock returns for each year between 2000 and 2020. The average return of these “high-return firms” during the year in which the firm experienced returns in the top decile was 159%. We then examined the evolution of the average Q of these high-return firms.

Figure 1 below summarizes the results of the exercise. Unsurprisingly, during the year when the relevant high-return firms experience the very positive shock (year 0), those firms have an average Q that is much higher than the Q of the other publicly traded firms firms. However, by the fifth year after high-return firms experienced the positive shock, the average Q of these firms is statistically and economically indistinguishable from the average Q of the other publicly traded firms. In other words, although “treatment firms” suffered a massive positive shock, cross-sectional comparisons of Q offer no evidence of such a shock after five years. For firms that suffer a shock that more closely resembles the plausible effect of a governance treatment, the impact on Q likely attenuates even faster.

Put differently, given the time between treatment and measurement of Q that is likely to have passed in cross-sectional studies, Q levels are not just a noisy proxy for the returns from treatment, they are no proxy at all. Thus, even in settings where it is not possible to study how the introduction of some governance treatment affects stock returns, cross-sectional Q regressions should not be employed as the next best alternative.

Figure 1: Long Term Effect of Shock on Q

See full paper for notes to the figure.

The bottom line is clear: Q regressions are a methodological dead end. Their continued use not only hinders progress in understanding the value implications of governance mechanisms but risks misleading scholars and policymakers.

Print

Print