Caleb N. Griffin is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law. This post is based on his article forthcoming in the Washington University Law Review.

Under the classic corporate governance framework, informed shareholders vote their own shares. However, this framework is increasingly a relic of a different era. Today, most investors hold equity assets indirectly through a variety of intermediary agents. As a result, the classic framework has been replaced in large part by a new model of intermediation.

Intermediation involves the decoupling of financial and voting rights, which weakens incentives to invest in informed governance. Regulators “solved” the problem of weak intermediary incentives by imposing an effective voting mandate—today, intermediaries face significant pressure to vote their shares even when such voting is not intrinsically valuable. As a result of the effective regulatory obligation to vote and weak financial incentives to vote well, intermediaries have developed a privately optimal strategy of high-volume, low-value, non-firm-specific, and compliance-oriented governance activity, which this article terms “mass corporate governance.”

Mass corporate governance generates a number of problems for investors, the corporate governance system, and the broader economy. Indeed, the scale of the problem has led some scholars to question whether certain intermediaries should vote at all, or, more modestly, to consider how such governance authority should be constrained.

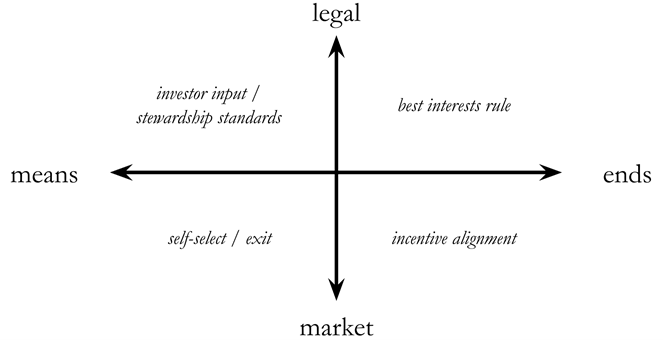

In a forthcoming paper, I construct a framework categorizing possible constraints on intermediary governance. This framework classifies potential constraints by their reliance on either legal or market forces and their target of either the means or ends of intermediated governance. Strategies to constrain governance costs can be situated in one of four quadrants, as shown in the figure below. Possible constraints in each quadrant will be discussed in turn.

Figure I: Theoretical Constraints on Intermediated Governance

![]()

Quadrant I: Legal Constraints on Ends — “Best Interests”

Beginning in the top right, the first quadrant discusses legal constraints on governance ends. The primary extant legal constraint on the governance costs of intermediaries is the “best interests” rule, which, as the name implies, requires intermediaries to vote in the best interests of their investors. However, this standard is quite weak—to my knowledge, out of the millions of votes cast by intermediaries, not a single vote has been found to violate this requirement, and it is difficult to imagine how future votes could do so with respect to any realistic ballot item.

Although this weakness initially seems specific to the current “best interests” rule, it is in fact endemic to ends-based legal constraints. The issue is that even seemingly strict and objective legal constraints on the ends of intermediated governance mask significant subjectivity. For instance, while some governance ends more obviously invite subjective considerations (e.g., Hart and Zingales’ shareholder welfare maximization, stakeholder theory), even when presuming a strictly enforced wealth maximand, a surprising amount of subjectivity remains. Put differently, even in the context of the theoretically most objective governance end—i.e., a strict obligation to maximize shareholder wealth—precisely which governance policies maximize shareholder wealth is the subject of vigorous academic debate. Thus, from the perspective of intermediary’s legal obligations, maximizing shareholder value is an exercise in subjectivity.

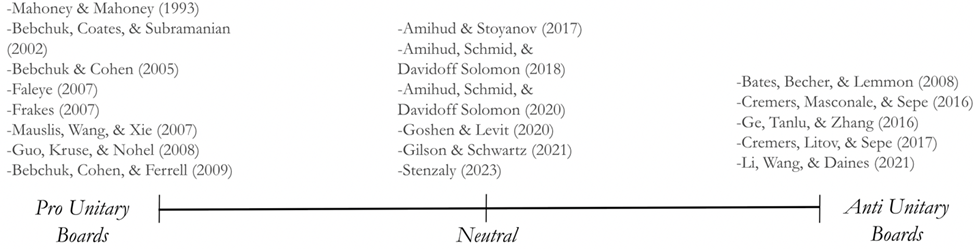

For instance, consider the empirical evidence on the unitary vs. staggered board debate. As Figure II below illustrates, there is significant support for the position that unitary boards maximize shareholder wealth. However, there is also substantial support for the position that staggered boards maximize shareholder wealth, as well as for the position that this governance issue is orthogonal to firm value.

Figure II. Empirical Research on Value Impact of Unitary v. Staggered Boards

From the perspective of an intermediary seeking to maximize investor wealth, which approach to board orientation best serves inventors’ interests? I argue that the lack of a definitive empirical consensus implies that all positions are legally permissible. When considering legal constraints on governance discretion, the question is not which position the weight of the evidence may favor, but which positions are legally permitted. Thus, even assuming that the “best interests” standard is interpreted in the most constraining manner (i.e., as a strict wealth-maximization requirement), it fails to meaningfully constrain intermediaries in the exercise of governance power.

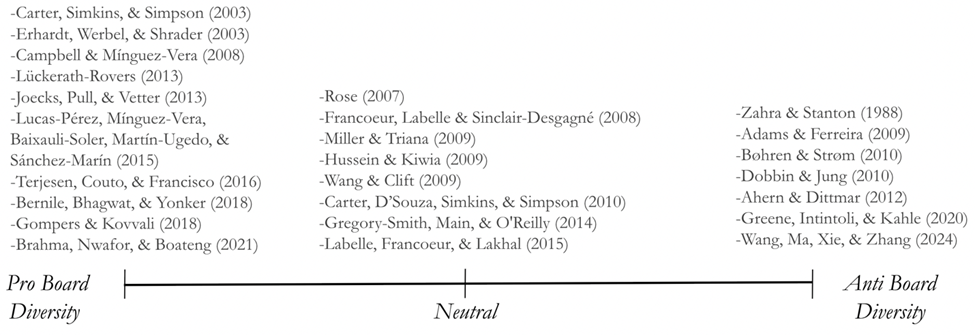

Similarly, consider the empirical evidence for board diversity:

Figure III. Empirical Research on the Value Impact of Board Diversity

As with unitary boards above, while there is a sizable body of research suggesting that board diversity improves firm financial performance, there is also research indicating that board diversity has a neutral or negative impact on firm performance. Intermediaries are thus legally permitted (and indeed do) vote in opposite ways on this issue, suggesting that here too their voting is not legally constrained by the empirical evidence.

The paper considers the empirical evidence for a number of other key governance topics, in each case finding that any voting decision is legally defensible. Ultimately, there is strong evidence that the best interests standard does not meaningfully constrain intermediaries in their exercise of governance discretion and that, more broadly, legal constraints on the ends of intermediated governance are unable to meaningfully limit agency costs.

Quadrant II: Market Constraints on Ends — Incentive Alignment

At a basic level, good stewardship will only be financially beneficial for a given fund if

(1) the governance changes increase prices enough, on an asset-weighted basis, to offset the fund’s investment in informed governance and (2) this fund’s governance investments were outcome-determinative for the particular ballot items that enhanced portfolio value to the requisite degree. The cost-benefit analysis in condition (1) is difficult to determine ex ante, with certain expenses and uncertain rewards, making such expenditures risky for asset managers. Fulfilling condition (2) (i.e., casting the pivotal vote) is also quite rare, even for the very largest funds.

Additionally, funds face indirect voting costs beyond their direct investments in informed governance. Among the most important of these costs is foregone share lending revenue, as funds must sacrifice such revenue to recall shares for votes. Because the record date for proxy voting represents a period of heightened borrowing demand and borrowing fees, the indirect cost of voting in the form of foregone share lending revenue can be surprisingly large. Indeed, Aggarwal et al. calculate that such costs can reach as high as 0.2% of the relevant share value, potentially exceeding Bebchuk and Hirst’s estimate for overall stewardship budgets at the Big Three. Thus, foregone share lending revenue represents a crucial factor in any cost-benefit calculation of intermediary financial incentives.

In the paper, I provide estimates of the financial incentives for the four largest intermediaries to vote on selected ballot items. The estimates of price impact, drawn from this meta-analysis, are intended only to be illustrative—for instance, some shareholder proposals will generate a greater price impact than average, while others may generate a negative price impact. The purpose is to illustrate how the financial incentives of intermediaries to vote vary based on a variety of factors, including price impact, fee structure, portfolio value, portfolio weight, ability to influence voting outcomes, and foregone share lending revenue. The following figure presents one such estimate:

Figure IV: Estimated Financial Incentives — High S&P 500

This table provides estimates of realized profits for various governance actions from the perspective of large intermediaries invested in a mega-cap company—Bank of America, with a market capitalization of approximately $365 billion.

|

Governance Type |

Impact |

BlackRock |

Vanguard |

State Street |

Fidelity |

|

Shareholder Proposal |

0.06% |

-$37,793.63 |

-$48,256.39 |

-$18,275.12 |

-$17,773.30 |

|

Direct Negotiations |

0.26% |

-$27,740.32 |

-$68,839.55 |

-$16,818.07 |

$8,747.44 |

|

Abstract Improvement |

1.00% |

$50,266.55 |

-$102,915.80 |

$7,285.27 |

$132,603.69 |

|

Hedge Fund Activism |

4.97% |

$1,115,571.69 |

$381,236.17 |

$433,174.52 |

$1,204,873.80 |

|

Proxy Contest |

6.77% |

$1,730,746.60 |

$737,034.83 |

$686,873.91 |

$1,774,368.59 |

|

Takeover |

15.31% |

$4,649,409.78 |

$2,425,101.77 |

$1,890,536.55 |

$4,476,305.02 |

As Figure IV shows, voting on certain governance items can generate significant financial impacts, while voting on others can generate significant costs. These costs are primarily driven by the stewardship expenditures allocated to such decisions, as well as the opportunity cost of foregoing share lending revenue to vote on a given ballot item.

The above table considers a relatively favorable situation—it estimates the incentives of the intermediaries with the largest equity ownership at one of the 25 largest publicly traded firms. Generally speaking, the financial incentives to vote are lessened for intermediaries with fewer assets (i.e., all other intermediaries) and for firms with lower market capitalizations (i.e., roughly 99.4% of all publicly traded firms). Moreover, although certain high-value governance items (e.g., proxy contests) at very large firms may provide adequate incentives for large intermediaries to invest in governance, such ballot items are comparatively rare. For instance, as few as thirteen proxy contests may go to a vote each year.

Ultimately, the overwhelming majority of ballot items on which intermediaries are tasked with voting will generate insufficient (and sometimes negative) financial incentives. Given the costs and uncertainties involved, most asset managers face strong incentives to free-ride on the governance investments of others while underinvesting themselves.

Quadrant III: Market Constraints on Means — Self-Selection & Exit

Although intermediaries generally face weak legal constraints on their ends and lack strong market incentives to align such ends with their principals, it is possible that market forces could instead constrain the means of intermediary governance. In particular, investors can, in theory, analyze each fund’s proxy voting records and engagements (i.e., the “means” by which intermediaries exert governance power), allowing them to select funds that match their governance priorities and to exit those that do not.

In practice, however, this is often either impossible or economically irrational. First, investors face significant constraints on their ability to switch investments (e.g., limited investment menus in employer-sponsored retirement accounts, capital gains taxes on asset sales outside of such accounts). Second, even if an investor believes the governance arrangements of another fund are superior, it is irrational to incur any switching costs or higher fees unless such investors’ shares are expected to influence voting outcomes. That is, unless an investor’s shares are outcome-determinative with respect to portfolio company governance outcomes, any switching costs or fees incurred will be in vain. Given the very low expected likelihood of any individual investor’s votes being pivotal, incurring switching costs or higher fees to achieve greater governance alignment has a negative expected value for most investors. Thus, despite the theoretical promise of market constraints on the means of intermediated governance, this channel of influence faces significant limitations.

Quadrant IV: Legal Constraints on Means — Investor Input

Finally, there are various policies targeting not the ultimate ends of intermediary governance, but, rather, the specific mechanisms employed to achieve such ends. Policies in this category generally require intermediary agents to solicit input from their investors and to use such input to inform their governance activities.

The key problem with such approaches is that their effectiveness in constraining intermediary agency costs is significantly limited by investor apathy and expertise. First, the type of specific, granular input that would actually constrain intermediary governance costs would be onerous for investors to provide (if, indeed, they possessed the expertise to do so at all). In contrast, investors would likely be more willing to provide general, high-level input on their governance priorities (e.g., “maximize shareholder wealth,” “support sustainable capitalism,” etc.). However, this type of more general input suffers from the same issues with subjectivity inherent in the ends-based constraints discussed above. As a result of this subjectivity, investor input directing an intermediary to “pursue wealth maximization” operates in practice not as a mandate, but as a grant of governance discretion to the intermediary that merely perpetuates the status quo. Thus, while input solicitation might be a useful strategy in certain contexts (e.g., assisting in the delegate selection discussed below), it fails as a broad-based solution to the agency costs of intermediaries.

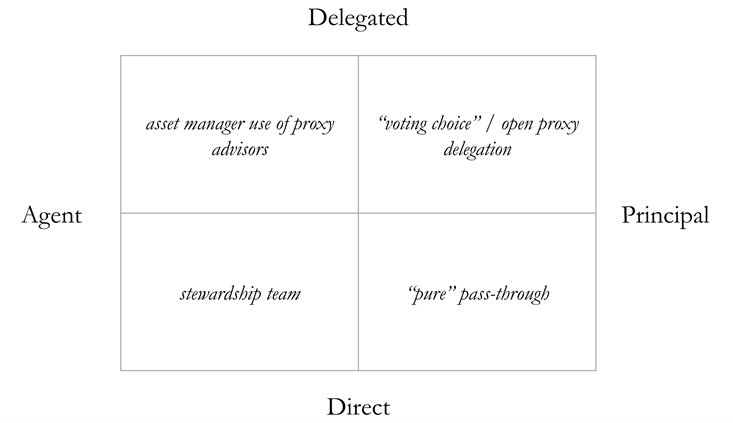

Beyond Constraints

At present, agents dominate the corporate governance arena, as reflected in the left half of Figure V. Intermediary agents directly exercise governance control through their stewardship teams, who craft proxy voting guidelines and engage directly with firm managers, and intermediaries also select proxy advisors to whom they may delegate a variable portion of their governance responsibilities. While the use of proxy advisors is not inherently problematic—indeed, they may be necessary for the modern mass corporate governance ecosystem to function—the resulting structure introduces multiple layers of intermediated agency, reducing accountability and compounding agency costs.

Figure V. Framework of Governance Authority

This figure portrays the potential allocation of governance authority between principals, agents, and their respective delegates, as well as a brief description of the dominant policy options in each category.

Rather than fighting to constrain the governance discretion of agents (or, compounding the problem, the behavior of their subagents or delegates), we should instead let principals choose to whom they wish to grant governance discretion. Much as intermediary agents may freely choose a proxy advisor to guide their proxy voting, so too should principals be granted this same right. Thus, I propose broadly focusing on policy solutions in the upper right quadrant of Figure V, whereby the principal may delegate voting authority, rather than an intermediary agent retaining such authority for themselves or delegating it to yet another agent.

Delegated voting is imminently feasible, having already been partially implemented via pilot programs at some of the largest asset managers. However, delegated governance would be enhanced by implementing two key policy solutions: “open delegation” and “proxy inference.”

Open Delegation

An open proxy delegation policy would permit principals to delegate governance authority to an unrestricted set of agents operating in a competitive market, in contrast to the status quo of intermediary gatekeeping. Existing voting choice pilot programs artificially constrain investor choice in two key manners. First, investor choice is directly constrained by intermediaries, who currently act as discretionary gatekeepers regarding which voting policies and delegates investors are permitted to select. Second, the current duopolistic market structure for proxy advisory services indirectly constrains investor choice, leaving investors with more limited options than would emerge from a more competitive market.

In addition to increasing the sheer volume of competition, an open proxy delegation policy would also alter the nature and target of such competition. To the extent that today’s market for proxy advisory services is competitive, it largely revolves around competition for the business of intermediary agents. In the status quo, proxy advisors are strongly incentivized to meet the “mass corporate governance” needs of agents—that is, to satisfy the preferences, goals, and regulatory requirements relevant to intermediaries—rather than those of their investor principals. By allowing investors to select delegates of their own choosing, proxy advisors would instead face competitive pressure to fulfill the goals and preferences of investor principals.

Many of the same arguments for proxy access and universal proxy are also relevant in this context. Just as there is value in shareholders being able to more freely select agents to oversee the firm, there is value in investors being able to more freely select their own delegates to oversee the governance of portfolio firms. In particular, given the relative weaknesses of fund-level governance, granting investors a greater voice in portfolio governance takes on additional importance.

Proxy Inference

Given that some significant fraction of investors will exhibit rational apathy, what inference should be made about their governance priorities? At present, the implicit default inference is that investment with a given intermediary and agreement with its governance priorities are coextensive. In other words, the choice to purchase equity assets from an intermediary is effectively treated as an affirmation of such intermediary’s proxy voting and other corporate governance policies. However, this inference assumes economic irrationality on the part of investors. As discussed above with regards to self-selection and exit, because virtually no investor’s votes will be pivotal with respect to governance outcomes, rational investors will generally view an intermediary’s governance policies as irrelevant to their investment decision. In consequence, the choice to invest with a given intermediary typically generates no inference regarding a rational investor’s support for the intermediary’s proxy voting policy.

Yet, inference is an essential remedy to voter apathy and collective action problems. Indeed, every intermediary governance policy, other than the rather cumbersome and unrealistic solution of passing through every ballot item to every investor, requires some level of inference on the part of the intermediary. So what inference is appropriate? Given that choice of intermediary is typically orthogonal to support for governance policies for economically rational investors, the best remaining evidence for an investor’s views likely comes from their fellow investors. As rates of delegated voting increase, it will become considerably more representative of general investor views; a recent Vanguard survey found that two-thirds of investors in employee retirement plans (and 58% of other investors) would participate in delegated voting programs, while only 8% said they would not. In such a situation, I argue that the best sources of inference about the voting preferences of silent investors are those of their participating counterparts. Thus, as participating levels in delegated voting programs increase, intermediaries should begin to implement fund-level mirror voting policies (sometimes referred to as “echo voting”).

Conclusion

Corporate governance has entered a second age of managerialism — only now, power is concentrated in the hands of intermediary asset managers, rather than firm managers. As with the prior era, it is possible to transcend “portfolio managerialism.” Just as enhancing shareholder power limited the agency costs of firm managers, enhancing investor power via the policies herein can limit the agency costs of asset managers. Current regulatory policies and private incentives have driven intermediaries to adopt a dominant, but suboptimal, mass corporate governance strategy. Allowing investors to freely select governance delegates and shifting the voting default would considerably reduce the governance-related agency costs of intermediaries.

Print

Print