Ray Garcia and Brian Schwartz are Partners, and David Stainback is a Principal at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on their PwC memorandum.

Boards are navigating an era of profound and persistent volatility. Global trade dynamics are in flux, shaped by shifting alliances and unpredictable tariffs. These disruptions have created ripple effects across companies’ strategic plans and supply chains, forcing companies to rethink revenue growth, financial performance, sourcing strategies, cost structures and operations. At the same time, economic signals remain mixed — consumer confidence is weakening and markets are increasingly reactive, yet external pressures are only part of the picture. Ransomware attacks, environmental disasters, unplanned CEO departures and other internal shocks can trigger crises just as suddenly and severely. In this environment, crisis is no longer a rare event but a recurring challenge.

To prepare for a crisis, companies are increasingly recognizing the need for an integrative resiliency program — one that integrates key capabilities like crisis management, business continuity, disaster recovery and incident response planning. Because a disruption could reach the level of crisis when resilience plans are overwhelmed and the tolerable level of impact is breached, these plans need to be working in an integrated and coordinated fashion with the crisis management plan to enable the organization to manage unforeseen disruptions, continue to deliver its strategic aims and return to a viable operating state despite the uncertainty.

In this context, boards of directors are being pushed to the forefront of crisis leadership. The board’s ability to provide clarity, stability and strategic direction has become critical to building resilience and long-term value creation in an era defined by flux. In particular, the board plays a key role in this crisis preparedness. A director’s role is to oversee that management makes the right decisions to support the long-term success and viability of the company. Earlier identification of potential crisis events and a better crisis response can have real benefits to the company’s brand and reputation, which in turn can translate to long-term shareholder value.

The board will want to see that management is ready to handle a crisis — before, during and after it occurs — whatever the crisis event might be. Board members can use their diverse perspectives and experiences to provide guidance and counsel to management when dealing with a crisis. And after a crisis, directors will want to see that the company continues to use lessons learned to improve its crisis planning.

The way business leaders prepare for and respond to disruptive events may determine how well the company will recover and whether it will emerge stronger. You may be thinking that your company has been through a crisis and so it knows how to deal with one. But performing a post crisis review and focusing on continuous improvement is likely to position the company to come out ahead in the next crisis. We’ll cover the key areas that should be addressed when considering your company’s preparedness.

Before a crisis

How effective is your company’s response plan?

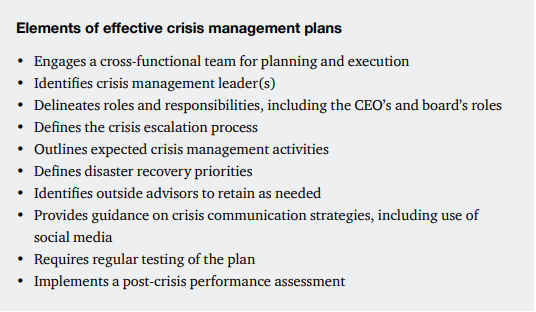

Comprehensive crisis plan

The best crisis plans are living documents. They are constantly updated and enhanced. It’s up to the board to push management on whether the company’s crisis response plan is up to date and ready to be deployed. This means confirming that the plan has all the key elements and the right decision points. The plan should be crisis agnostic with the ability to flex to address various types of crises. It should also reflect lessons learned from what worked and didn’t work in the company’s own crisis experiences. The plan may also reflect insights learned from other companies whose crises have played out in the media. It should outline the designated crisis leader and the right crossfunctional crisis team members, and it should clearly define roles and responsibilities. It should also go beyond these topics to include outside expertise needed and the communication strategy and plan. Overall, the board should have confidence that the company can react quickly and effectively when a crisis event occurs.

The board will want to evaluate whether the plan accounts for all critical elements. It should also assess whether the plan has enough detail, so the crisis team knows what to do when confronted with a problem. But it’s important to balance that detail with practicality. It may seem obvious but it’s worth stating. Every crisis is different, and there is no one-size-fits-all crisis plan.

As the board discusses the crisis plan with management, it will want to focus on who will be the designated crisis leader. The right person will have a senior leadership position and appropriate expertise, as well as stature and visibility across the business. Some companies may identify one person to consistently lead the crisis response team; others might have a few individuals lined up to lead, depending on the nature of the crisis. Either way, the board will want to see that the company’s plan addresses the particular crisis topic.

Another critical area for a board to look at is whether the crisis plan articulates a management-level governance structure that supports effective and timely decision-making, communications and accountability. As companies have dealt with crises, they likely experienced many competing priorities that needed immediate attention. The board will want to see that the crisis plan articulates an approach to address this challenge with a company-wide response. The board can ask about protocols that should be put in place for different workstreams, like communications, legal and regulatory, and operations, to help with decision-making and working closely together during a crisis.

The board should also ask whether the crisis plan is aligned, coordinated and tested with the disaster recovery plan and business continuity plan. There may be other plans too, like an incident response plan if there is a cyber breach. These plans are often developed individually at a company, but a centralized approach that includes and tests all plans together is critical for a company’s resiliency. True operational resilience allows an organization the ability to maintain critical operations during disruption and requires the integrated activation of these various types of response plans and escalation up to the crisis management plan.

Business continuity plan: Commonly includes identifying mission-critical systems, strategic decisions, and policies and procedures on maintaining business functions during a crisis (e.g., manual processes to continue operating) as well as related roles and responsibilities.

Disaster recovery plan: Includes policies and procedures for backing up data, restoration procedures for disaster recovery sites and systems, and related roles and responsibilities.

Incident response plan: Includes actions to take in response to specific incidents, such as cyberattacks or data breaches, including detection, containment and recovery processes, as well as related roles and responsibilities.

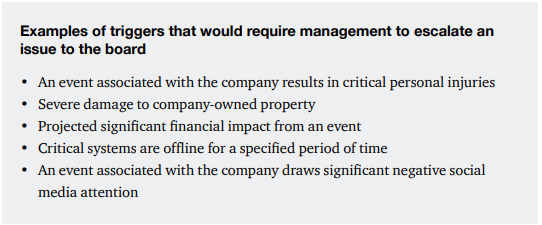

Timely board escalation

When a crisis occurs, the board needs to be informed at the right time. Some types of crises should trigger almost immediate notifications to the board, while in other cases, it may be appropriate to wait until the next board meeting. Recent crises that the company has navigated can provide an opportunity for the board to reflect and assess when it was notified and whether that timeline was appropriate. If not, the board (working with management) can further define the board escalation process in the crisis plan.

An essential part of timely notification to the board will be for the board and management to define a “crisis” as well as the quantitative and qualitative triggers that will cause notification considering a variety of possible scenarios with management that would require board involvement.

Get feedback on testing

With crises becoming more complex and frequent, a crisis response plan is likely to need ongoing attention. The board will want to do its part in keeping this topic on the forefront by periodically putting crisis oversight on its agenda. The board will want to not only get an update from management on the current crisis plan but also feedback on how the plan is continuing to be tested and what additional training and follow-up actions have been identified to improve the plan.

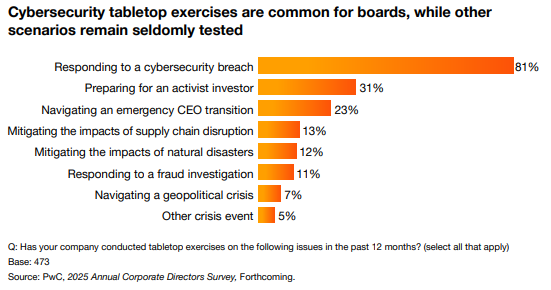

The board can ask management about the different scenarios that it used to simulate a crisis and test the plan. Of directors that say their boards have conducted tabletop exercises in the last 12 months, the majority (81%) of them have been focused on responding to a cybersecurity breach. However, other critical crisis scenarios — such as mitigating the impacts of supply chain disruptions, addressing natural disasters and navigating geopolitical crises — have been less frequently tested. It’s essential to evaluate scenarios that differ from crises the company has already encountered. Continual testing of the plan helps the crisis team understand how well the company would respond in real time and whether roles and activities align with the plan’s intentions. Testing can help identify areas of confusion and reveal gaps in the crisis response plan.

The board should make sure senior executives — including the CEO — are involved in crisis response plan testing. They set the tone and have critical roles.

The board’s crisis plan

Beyond management’s crisis plan, the board should have its own plan as well. This plan acts as a layer on top of management’s plan. It should capture key elements of the board’s governance structure, communication strategy and succession planning. The plan should also capture lessons learned from directors’ experiences with corporate crises. Management should weigh in on the board’s plan to aid alignment of expectations. Elements these plans may include are:

- Preferred governance structure depending on the nature of the crisis. Will the board establish a special committee, or use an existing committee or the full board? Who will serve on the special committee?

- A board communication strategy. Will there be a board liaison for the crisis team? How will board members communicate with one another? Will someone from the board need to be “camera ready”?

- Temporary succession planning. Is there a director who could step in temporarily to lead the company, the board or one of its committees, if necessary?

Top ten pitfalls of crisis management

Every crisis offers a learning opportunity. We’ve captured the top ten mistakes we have observed management make when preparing for or dealing with a crisis. While these items are management’s responsibility, the board also plays a role. Directors will want to discuss and challenge management on how it is proactively preparing for and managing these pitfalls so that the company can successfully navigate through the crisis and emerge stronger.

Before a crisis happens:

- Having too many cooks in the kitchen: Identifying a crisis leader, team members, roles, responsibilities and a governance structure is critical to a successful response.

- Uncoordinated priorities: In the heat of a crisis, a weak governance structure — exacerbated by competing internal priorities — can lead to miscommunications, both internally and externally, which companies may later regret. Tackling the crisis piecemeal through siloed activities may sound like a good idea, but it can be more damaging than helpful.

- Not recognizing familiarity bias: It’s natural to think of the next crisis in terms of what’s been splashed across the headlines. It can also lead to potential blind spots. The next crisis that the company faces may not look anything like those that have dominated headlines — and it may not be the one management expects.

- Relying solely on “having” a crisis plan: “I have a plan” does not equate to a crisis response. While many companies say they have a crisis response plan, they also frequently forget to turn to it when a crisis occurs. A plan is only as good as its latest tests and training. Testing should be conducted frequently enough to create “muscle memory” to follow the plan when a crisis hits.

During a crisis:

- Leaping before looking: Clear and accurate facts are not typically available as a crisis begins to unfold. Beware of the tendency to succumb to stakeholder pressures to take immediate action before the company has a grasp of the full picture.

- Not seeing the crisis for the trees: A too-narrow focus on the immediate or perceived issue, without considering other potentially impacted areas, is understandable. But that can lead to a cascade of secondary shocks and crises.

- Minimizing the problem and paying for it later: Failing to acknowledge the severity of an issue — and not treating it with the respect it deserves — may severely damage a company’s reputation. History is replete with examples of companies that learned this the hard way, coming across as nonchalant, inauthentic or even uninformed about the issue at hand.

- Neglecting crucial stakeholders, including employees: When communicating under pressure, many companies tend to focus on one or two stakeholder groups at the expense of other, possibly more critical ones. Unfortunately, that can include employees, who are frequently overlooked in the communications strategy.

- Losing authenticity — and credibility: Conducting the response in a way that is not aligned with the company’s values can also damage the brand’s integrity — and the trust of its stakeholders — long after the crisis is over. After a crisis occurs: 10. Not acting on lessons learned After a crisis, many companies focus on what happened and what to do next — but often overlook the deeper questions of how and why it occurred. Without acting on root cause analysis, organizations may miss the opportunity to strengthen resilience and may remain vulnerable to future disruptions.

After a crisis occurs:

- Not acting on lessons learned: After a crisis, many companies focus on what happened and what to do next — but often overlook the deeper questions of how and why it occurred. Without acting on root cause analysis, organizations may miss the opportunity to strengthen resilience and may remain vulnerable to future disruptions.

During a crisis

How does the board help management successfully navigate?

Once a company is in crisis response mode, the stakes are high. Companies — including the board — may be judged not just on the issue itself but on how effectively they respond. And if the response is mishandled, the impact may reach far beyond an operational problem. A mishandled response can quickly escalate beyond an operational issue, which may cause lasting damage to reputation and brand.

But as many boards and management will admit, responding to a crisis is hard. The scope of the crisis can be uncertain. Facts can be murky and inaccurate. News and rumors spread quickly through social and traditional media, adding to the pressure to respond quickly. On top of that, the board and the company may face pressure from stakeholders, the media and the public to take action — even before it has the full picture.

As boards reflect on recent crises, they should discuss with management what went well and what didn’t go well in the company’s response. A critical assessment that targets improvements and pitfalls to avoid when a future crisis occurs is valuable.

History is replete with examples of companies who failed to acknowledge the severity of an issue and treat it with the respect it deserved.

Challenging the communications strategy

Having the right communications strategy internally and externally is critical when responding to an event. A company will want to tell its own story about how it is addressing the crisis. Without a communications strategy, a company may lose control of its story. This may result in damage to crisis efforts and company reputation. For these reasons, the board should understand and challenge management’s strategy on what the company should say, who should say it and when they should say it. Stakeholders will want to know how the company is responding, even if the answer is that the company does not know the answers yet. Perception matters, and acknowledging the issue is often more advantageous than staying silent.

Frequent communications and updates on the crisis are a necessity. As the crisis continues to unfold, directors should expect to get clear messaging on what is happening, who is accountable, how the company is responding and what will be done next to address problems. The board should push back if the communications don’t appear to align with the company’s core values, which can build significant trust with stakeholders long after the crisis is over.

Typically, the board should expect to see outside advisors built into the crisis plan and response.

- Law firms can advise on required communications, such as those that must be made to regulators. They can offer perspective on any voluntary disclosures and help the company avoid being exposed to increased liability.

- Crisis communications experts can guide senior management on a communications strategy, including how frequently to make statements despite the absence of additional information.

- Crisis management firms can also provide strategic advice and additional resources to help a company balance responding to a crisis and running the business.

In assessing the company’s response to recent crises, the board should ask management to reflect on whether it had all the right parties and experts involved from the start. Was there anyone that needed to be included in the last crisis that wasn’t part of the plan? If so, these learnings should inform an update of the crisis plan.

While the CEO is typically the company’s main spokesperson, the board should be aware that this may present a problem if the CEO is at the center of the crisis. Such cases often require someone else to step into the spokesperson role. That may be an interim company leader or even the board chair or lead director. The board should have a ready backup for the CEO in terms of a spokesperson as part of the board’s crisis response plan should the situation warrant.

It can be valuable for the board to regularly review feedback from inside and outside the company to gauge how well the company is responding. Directors can follow news and social media channels to stay current and get “sentiment analysis” from outside experts. Directors can also hold executive sessions with these experts just to be sure they’re getting the full picture. The board will need to challenge management and demand course correction if it senses that the messages aren’t working.

Management and the board should have an agreed-upon approach for crisis communication. The board should expect regular updates on how the situation is being managed. While communication typically increases during a crisis — with more frequent updates and meetings — the focus should be on getting information that is timely, relevant and aligned with decision-making needs.

A board may elect to designate a liaison to interact with the crisis team, use the full board or use a crisis committee, depending on the nature of the crisis. Frequent, standing, board calls are often essential during a crisis, giving all members the chance to stay informed, ask questions and provide input as the situation unfolds — sometimes happening daily or even more often at the peak. Whatever practices the board adopts, what is critical is that it works for the board and for the situation. By updating the board-level crisis plan with the communication preferences learned through its experiences, the board can try to create a better experience for the next time.

Addressing all stakeholders

When communicating under pressure, companies tend to focus on one or two stakeholder groups who have the loudest voices at the expense of other, possibly more critical ones. The board plays a role in helping management consider the diverse needs and interests of all stakeholders in the communications strategy. The board will want to ask the crisis team about feedback from stakeholders, see that the company’s response resonates with them and consider what additional actions can be taken to address concerns.

A crisis is, and always will be, a human event. Only human beings can manage a crisis effectively, and human beings are the most affected by it.

Internal communications are as important as external communications. In a crisis, management may be so externally focused that they overlook communications with their employees. Boards will want to make sure this critical stakeholder group gets attention. Employees are often the company’s strongest advocates. Actively engaging with them during a crisis can help with attraction and retention of talent. Employees will continue to perform their responsibilities, deal with customers and interact in their communities. They need to be informed about the crisis, receive regular updates and know where to go to get more information and ask questions.

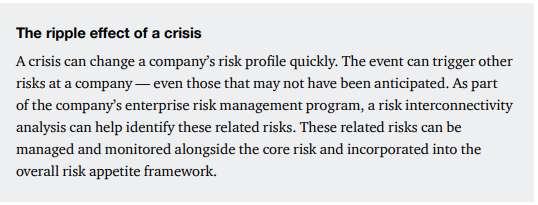

Getting ahead of other risks

While the crisis team has to focus on the current crisis, the board will want to maintain a focus on the long term. Dedicated resources should be focused on impacts in other areas of the business, particularly if a crisis is long term. Risks and opportunities may present themselves over the next three, six, nine months or longer. There may be an impact on other business relationships, supply chains, workforce morale and job security, to name a few. Getting ahead of these areas helps a company emerge from a crisis even stronger.

Remembering the rest of the company

It’s easy for companies to get overwhelmed in a crisis. The management team will likely need to lean on the board for guidance. The board may need to step up their day-to-day involvement and oversight of management to keep the company on track. It demands a significant amount of time and energy from the CEO and senior leadership, but losing sight of the ongoing business can make the impact of the crisis worse. Competitors will be watching for ways to profit from a company’s woes. And other more nefarious actors — like cybercriminals — may also try to exploit various vulnerabilities, relying on the fact that management is distracted. The board will want to monitor that the company is staying focused on the company’s operations in the midst of a crisis.

After a crisis

How do we get better?

Once a crisis has passed, the tendency is to get back quickly to “business as usual.” But unless there’s a thoughtful post-event review and adjustments, if needed, to the crisis response plan, the company risks repeating any mistakes it made in future crises.

Root causes and improved response plans

Directors will want to understand the root causes of the crisis the company has just weathered. This allows the board to weigh in and discuss whether appropriate follow-up actions have been taken. There may need to be an investigation based on the nature of the crisis, and management will often lead such investigations. But if management itself seems to be at the heart of the crisis, or if the event was significant enough, it may make sense for the board to decide whether an independent investigation is needed.

In addition to looking at root causes, there should be a continuous improvement mindset for the crisis response plan. Directors will want to discuss with management what was learned and how the plan will be improved as a result. It also can be valuable for management to get an external, objective assessment of the company’s crisis response from a different perspective from those that participated in it.

Don’t forget a post-event review

Once the crisis is over, a critical assessment of how well the company responded is valuable. The board will want to have a candid and open discussion with management. It can consider asking management the following questions:

- Right crisis team: Did we have the right executives on the crisis team? Did we have the right internal subject matter experts and did we leverage the right outside experts? Is the team sustainable in the event of a long-term crisis?

- Useful plan: Did we have an enterprise-wide crisis response or continuity plan? Did we use it? Was it effective?

- Clear accountability: Was it clear who had decision-making authority? Did it take too long to make decisions? Were there any bottlenecks in the process?

- Effective and timely communications: Were our communications to key stakeholders on point? Were they timely and was the frequency right? Could we have been bolder?

- Stakeholder focus: Did we consider all of our stakeholders? Did we address their key concerns? Were there a lot of unanswered questions?

- Response to feedback: Were we agile enough to respond to feedback from our stakeholders? From the market? Did we understand what our competitors were doing and were we able to react or respond quickly, if appropriate?

- Useful technology and data: Did we have the right tools to assist in our crisis response? Did we have the data we needed to make critical decisions in a timely manner? Is there a technology solution that we should have employed that would have tracked activities and provided data quickly and more easily?

Conclusion

Knowing the company has a sound crisis response plan can give directors greater confidence that management is ready to respond to a future crisis. Since many directors have had to deal with crises in their executive roles, they can use their experience to advise management. The better the plan and the more coordinated the effort to test and execute it, the more likely it will help a company handle a crisis quickly and effectively. Robust crisis preparedness can be viewed as a competitive advantage.

Print

Print