Robert J. Jackson, Jr. is a Commissioner at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. This post is based on his letter to Congresswoman Carolyn B. Maloney, Chair of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship, and Capital Markets, available here. The views expressed in the post are those of Commissioner Jackson and do not necessarily reflect those of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the other Commissioners, or the Staff. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Corporate Political Speech: Who Decides? by Lucian Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson Jr. (discussed on the Forum here); and The Untenable Case for Keeping Investors in the Dark by Lucian Bebchuk, Robert J. Jackson Jr., James David Nelson, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here).

November 18, 2019

The Honorable Carolyn B. Maloney

Chair, Subcommittee on Investor Protection, Entrepreneurship, and Capital Markets United States House of Representatives

2308 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515-3212

VIA ELECTRONIC DELIVERY

Dear Chair Maloney:

Thank you for your July 15 letter regarding my research on the need for transparency in corporate political spending—and your leadership in urging the SEC to ensure that our rules protect American families who invest in public companies that spend investor money on politics. I very much appreciate the opportunity to share further details on this work.

I first raised these concerns while serving as co-chair of a bipartisan group of scholars who petitioned the SEC to require disclosure of how public companies spend investor money on politics. [1] More than 1.2 million Americans have written to the SEC to support that petition, and a bipartisan group of SEC officials has called our proposal a “slam dunk.” [2] But Congress has used the appropriations process to block the Commission from requiring disclosure in this area.

Without disclosure, executives can spend shareholder money on politics in a way that serves the interests of insiders, not investors. That’s why shareholders seeking accountability in this area often put political spending disclosure proposals on the corporate ballot. But working Americans whose savings are spent on politics don’t vote on those proposals themselves. Instead, they invest their savings through large institutions who vote on their behalf. And while ordinary investors overwhelmingly favor transparency in this area, the biggest institutions consistently vote their shares to keep political spending in the dark. [3]

In your letter, you asked me to review legislation that would require public companies to disclose whether and how they spend shareholder money on politics. As I have written before, such a requirement would bring much-needed accountability to corporate political spending. [4] In responding to your letter, my Office conducted additional analysis of investor interest in corporate spending on politics. Our findings show why this area deserves further attention:

- First, the case for requiring disclosure of corporate political spending is strong. Today, corporate executives are free to spend shareholder money on politics in a way that favors insiders’ interests over investors’—for example, by directing spending toward causes that executives personally support. As in other areas where executives’ interests conflict with those of the company’s owners, investors can only hold insiders accountable for the spending of shareholder money on politics if that spending is disclosed.

- Second, although over 70% of ordinary American investors favor disclosure of political spending, their shares are nearly always voted against proposals to require transparency. [5]The reason is that some institutions managing Americans’ savings have chosen to vote against shining light on corporate political spending. Those institutions provide investors with either vague or nonexistent disclosure of that choice, raising the concern that investors don’t understand how their money is being voted when it comes to corporate spending on politics. [6] The legislation you asked me to review would give shareholders oversight of corporate political spending; it is crucial that ordinary investors understand how the institutions who manage their money would use that power.

Debates over corporate political spending invoke strongly held views about the Nation’s political process. I am aware that many would prefer that the securities laws not address a subject as sensitive as this one. But as a Commissioner, those debates are beyond the scope of my work. My job is to give investors the information they need to hold those who manage their money to account—a charge that does not change because that information involves political spending.

The lack of SEC rules in this area leaves investors without information about how their money is spent on politics. For that reason, I support legislation requiring political spending disclosure. Moreover, some institutions consistently vote American families’ money to keep corporate political spending in the dark, and I am concerned that investors are unaware of that fact. That’s why today I’m calling upon those institutions to tell investors where they stand on transparency of corporate spending on politics.

I. The Case for Requiring Disclosure of Corporate Political Spending

For generations, our securities laws have evolved in response to changing circumstances and investor interests to give shareholders information they need about the companies they own. Because corporate political spending is not transparent under current law, investors need disclosure to hold executives accountable when they spend shareholder money on politics.

A significant amount of corporate political spending is not disclosed under current law. That’s because public companies contribute investor money to intermediaries that do not disclose who made the contributions or how much they contributed. A study I published in 2013 showed that just eight intermediaries spent $1.5 billion of investor money on elections over six years. Investors have no way to know whether companies they own were the source of that money. [7]

While other types of corporate political spending are disclosed under federal election law, those disclosures are not designed to protect investors. [8] And those disclosures describe only companies’ federal political spending; additional data, from a variety of scattered sources, are needed for investors to hold insiders accountable for spending on state-level politics.

The result is that most public-company political spending occurs under investors’ radar. This would not be worrying if executives’ interests in political spending were aligned with those of shareholders. But when it comes to politics, insiders’ interests can diverge from investors’. Political spending has consequences beyond the firm’s performance—like advancing insiders’ preferred political views—and executives’ decisions may be influenced by those consequences. Since shareholders do not sort themselves according to their political views, there will often be a divergence between insiders’ and investors’ preferences on political spending. And studies show that political spending is associated with corporate governance problems that affect firm value. [9]

The standard securities-law solution to conflicts like these is disclosure. That’s why SEC rules require disclosure on corporate directors’ decisions on executive compensation: directors have reason to favor executives in decisions on pay. [10] That’s why SEC rules also require public companies to give investors information about transactions between the company and insiders. [11] Just like in these areas, there is evidence linking corporate political spending to worse long-run performance. And just like in these areas, disclosure would help ensure that corporate political spending is aligned with the interests of investors—not corporate insiders.

II. How Large Institutions Help Keep Corporate Political Spending in the Dark

Since there are no SEC rules in this area, investors have used the shareholder proposal process to demand disclosure on a company-by-company basis. That’s why political spending disclosure is the second-most common subject of shareholder proposals at U.S. public companies. Although shareholder support for these proposals has doubled over the last decade, and given that the overwhelming majority of investors favor disclosure of corporate political spending, support for these proposals is lower than investor preferences would suggest. [12]

The reason is that the average American investor doesn’t vote shares directly on these issues. Instead, they save for education and retirement through large institutions who vote shares on their behalf—and three of the largest institutions in America almost never support proposals that would require disclosure of corporate political spending.

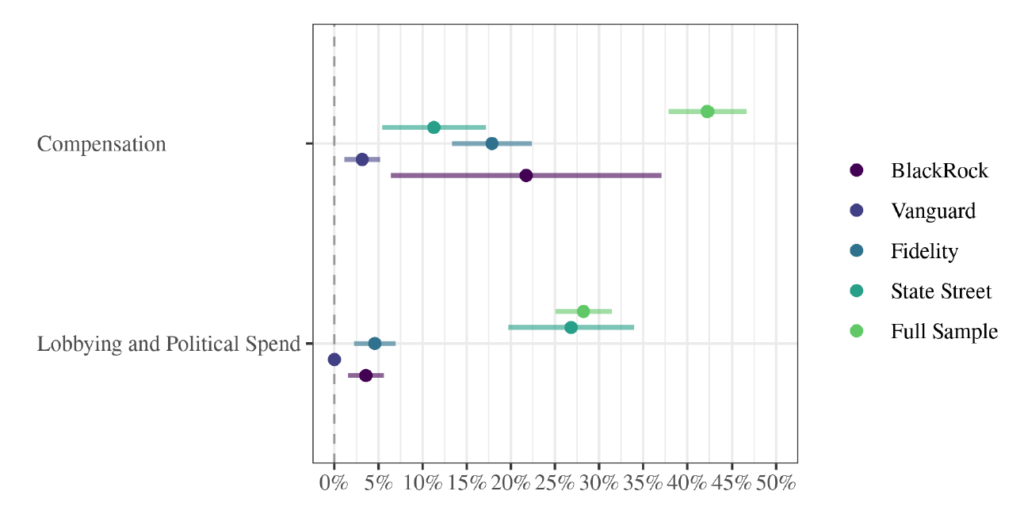

To better understand investor preferences in this area, my Office extracted voting data for hundreds of the largest institutional investors over the last fifteen years. I then examined how those institutions—especially the four largest—vote on shareholder proposals regarding two corporate-governance issues: executive pay and political spending. Figure 1 describes both how often the institutions vote “yes” and how their votes vary by company and over time:

Figure 1. Institutional Investors’ Votes on Corporate Governance Matters. [13]

Figure 1 shows that these institutions take a similar approach to voting on executive-pay proposals. To be sure, they vote to support such proposals at different rates—BlackRock votes “yes” much more often than Vanguard, for example. But all of the institutions’ votes vary by firm and over time, reflecting the company-specific consideration that such proposals require.

Political spending proposals are different. On those proposals, three of the largest four institutions vote “yes” less than five percent of the time—even though, as my coauthors Lucian Bebchuk, James Nelson, Roberto Tallarita and I show in recently released research, other institutional investors frequently support those proposals. [14] Even more strikingly, for the largest institutions there is virtually no variance by company or over time, although one could imagine the strength of the case for disclosing political spending to vary depending on the circumstances. In short, regardless of the company or situation, three of the four largest stewards of ordinary Americans’ retirement savings almost always vote to keep corporate political spending in the dark. [15]

I was surprised to find that—despite investors’ clear preference for transparency—these institutions have so unanimously voted against disclosing corporate political spending. Given the strongly held views on the subject, I wondered whether ordinary investors were aware of these facts. So my Office examined the largest institutions’ proxy-voting guidelines, which tell investors how to expect their shares to be voted at each institution.

The evidence shows that, in most cases, these institutions offer little or no transparency to ordinary investors about their voting record on corporate political spending. [16] For example, Vanguard has voted investors’ money against disclosing such spending across 817 shareholder proposals without ever voting in favor of transparency. That record suggests that Vanguard has determined, as a matter of policy, to vote against such proposals. Yet Vanguard’s proxy-voting guidelines do not disclose such a policy; indeed, they say nothing on this subject. [17]

Of course, this evidence does not establish that any institution should vote differently on any particular shareholder proposals. [18] It does, however, raise the concern that ordinary investors do not understand how the institutions managing millions of American families’ money vote on disclosure of corporate political spending. Contrary to those investors’ preferences, three of the largest institutional investors in the United States consistently vote to keep corporate political spending in the dark. American investors deserve to know that.

* * * *

The legislation described in your letter, by requiring public companies to disclose how they spend shareholder money on politics, would help investors hold executives accountable when they engage in corporate political spending. Because a significant amount of political spending currently occurs under investors’ radar, disclosure is needed for investors to know whether, and how, corporate insiders are spending their money on politics.

Without an SEC rule in this area, investors have filed shareholder proposals at hundreds of public companies demanding transparency of corporate political spending. Those proposals are overwhelmingly popular with ordinary investors. But the institutions who manage millions of American families’ savings vote to keep corporate political spending in the dark on a one-size- fits-all basis—without making that clear to investors.

While I know that corporate spending on politics raises strong views about our political process, in my view your letter reflects a basic principle underlying the SEC’s mission. Our laws should give investors the information they need to know how their money is being spent and voted—even when it comes to corporate political spending. That’s why the legislation you asked me to review could be so helpful to our work. And that’s why I am calling upon institutions who manage ordinary Americans’ money to be clear with investors about how they vote on this issue.

Thank you again for your letter—and for your work to ensure that the SEC gives ordinary investors the information they need on how their money is used and voted on political spending. Should you have any questions, or if your Staff would find further information helpful, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Very truly yours,

Robert J. Jackson, Jr.

CC: The Honorable Maxine Waters

Chair, House Financial Services Committee United States House of Representatives 2221 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515-3212

Endnotes

1Letter from Comm. on Disclosure of Corporate Political Spending to Elizabeth M. Murphy, Sec’y, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm. (Aug. 3, 2011) [the Petition].(go back)

2See Dave Michaels, SEC Should Require Political-Spending Reports, Ex-Chairs Say, BLOOMBERG (May 27, 2015); Letter to SEC Chair Mary Jo White from William Henry Donaldson, Arthur Levitt, and Bevis Longstreth (May 27, 2015).(go back)

3Mason-Dixon Polling &Amp; Research, Corporate Political Spending: A Survey of American Shareholders 6 (2006) (finding that some 73% of American shareholders believe that corporate political spending is undertaken to advance the private interests of executives rather than the interests of the company).(go back)

4Lucian A. Bebchuk & Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Corporate Political Spending: Who Decides?, 124 HARV. L. REV. 83 (2010); see also Lucian A. Bebchuk & Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Shining Light on Corporate Political Spending, 101 GEO. L.J. 923 (2013).(go back)

5Mason-Dixon Polling &Amp; Research, supra note 3, at 4.(go back)

6My concern is not that any particular institution has run afoul of its legal obligations by failing to disclose their position on these matters more clearly to investors. Instead, my claim is simply that these institutions can and should do more to make sure that ordinary American investors understand how their retirement savings are voted on corporate political spending.(go back)

7Bebchuk & Jackson, supra note 4, at 932 & tbl. 1 (2013). One might argue that investors can simply assume that public companies make contributions of this kind and price that expectation into investment decisions. But that’s not possible: the scant evidence available in this area makes clear that there is substantial variance among public companies with respect to political spending through intermediaries. See id. at 934 (describing evidence that “there is substantial variance among companies” of similar industry and size with respect to political spending).(go back)

8For example, corporations that choose to provide indirect support to candidates for office are required to disclose that support under federal election law. See 2 U.S.C. § 434(f)(1), (4).(go back)

9See, e.g., Rajesh K. Aggarwal, Felix Meschke & Tracy Yue Wang, Corporate Political Donations: Investment or Agency?, 14 Bus. & Pol. 1 (2012) (firms with worse corporate governance engage in more political spending); Marianne Bertrand, Matilde Bombardini, Raymond Fisman & Francesco Trebbi, Tax-Exempt Lobbying: Corporate Philanthropy as a Tool for Political Influence (NBER working paper 2018).(go back)

10See, e.g., 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(b) (mandating disclosure on boards’ executive-pay deliberations).(go back)

11See id. § 229.404(a); see also John W. White, Director, Division of Corporation Finance, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Remarks Before the Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals (Oct. 12, 2006) (“I have heard very intelligent people assert, quite emphatically, that a charitable donation cannot trigger required disclosure . . . . I respectfully disagree. . . . Imagine [a] company makes a sizeable . . . donation to an environmental organization [that] employs the CEO’s son?”).(go back)

12Mason-Dixon Polling &Amp; Research, supra note 3, at 4.(go back)

13To estimate the confidence intervals in Figure 1, I first calculate the average fund support for proposals in each area and then calculate the standard error of that mean. Because of the large number of fund-year votes, the assumption of homoscedastic standard errors results in severely downward-biased estimates due to the potential correlation of residuals across funds and time. Assuming homoscedastic standard errors in this setting produces confidence intervals so small that they are visually indistinguishable. Thus, clustering produces more realistic standard error estimates, for the reasons given in Mitchell A. Petersen, Estimating Standard Errors in Finance Panel Data Sets: Comparing Approaches, 22 Rev. Fin. Stud. 435 (2009).(go back)

14See Lucian A. Bebchuk, Robert J. Jackson, Jr., James D. Nelson & Roberto Tallarita, The Untenable Case for Keeping Investors in the Dark, 10 Harv. Bus. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2020) (“Furthermore, an analysis of mutual funds’ voting shows that in 2018 most of the 115 mutual fund groups indexed in the Fund Votes database consistently supported shareholder proposals calling for disclosure of corporate political spending (although the largest fund groups, Vanguard, Fidelity, and Blackrock, traditionally vote against or abstain on such resolutions). In particular, 53 fund groups supported at least three quarters of the election spending disclosure resolutions voted upon and 34 of them supported all such proposals. In contrast, only 23 groups failed to support a single political spending disclosure proposal.”). Solely for your reference, I have attached a current draft of this study to this letter as Annex A.(go back)

15My Office studied institutional votes on 817 shareholder proposals on lobbying and political spending over a fifteen-year period in the Institutional Shareholder Services Voting Analytics database, which covers the largest 300 fund families and issuers in the Russell 3000 index (with slight variations in coverage in that period). According to that database, BlackRock voted in favor of these proposals less than 2% of the time. Even more strikingly, Vanguard never voted in favor of any of the proposals my Office examined.(go back)

16Of the four voting guidelines my Office examined, only BlackRock had an explicit proxy voting policy regarding corporate political activities. See BlackRock Proxy Voting Guidelines for U.S. Securities 1 (2019) (“We generally believe that it is the duty of boards and management to determine the appropriate level of disclosure of all types of corporate activity, and we are generally not supportive of proposals that are overly prescriptive in nature.”).(go back)

17It could be argued that Vanguard views political-spending proposals as “environmental and social proposals,” on which their guidelines say the firm will vote on a “case-by-case” basis. See Vanguard Funds, Proxy Voting Guidelines for U.S. Portfolio Companies 10, 13 (2019) (explaining that a “fund will vote case- by-case on all environment and social proposals”). If so, that seems even more unclear, because it is hard to see how investors could understand a “case-by-case” voting policy to lead to zero “yes” votes on 817 proposals.(go back)

18For a thoughtful and forceful case for why these voting patterns can raise concerns about the legitimacy of corporate spending on politics, see Leo E. Strine, Fiduciary Blind Spot: The Failure of Institutional Investors to Prevent the Illegitimate Use of Working Americans’ Savings for Corporate Political Spending, 97 Wash. U. L. Rev. (forthcoming, 2020).(go back)

Print

Print