Matt DiGuiseppe is Managing Director at the Governance Insights Center, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on his PwC memorandum.

Part I: Introduction

Shareholder activism today

The nature of shareholder activism, the key players, their preferred methods and their typical targets all tend to shift along with investment and business trends. They are influenced by market pressures, stores of capital and hot topics in governance. But during bull and bear markets, during recessions and times of growth, activists continue to look for opportunity, and companies continue to find themselves in the crosshairs.

The role of the board in an activist environment is an important one. Directors can help ensure the company anticipates which activists might target the company, and which issues they might raise. By being familiar with activism trends, they can encourage management to proactively address common issues that are attracting attention. In many cases, these issues deserve careful attention and should be reflected in company strategy. The board also plays a key role in shareholder engagement, and in responding to activist requests and demands. What do boards of directors need to know to navigate this environment? What can they learn from shareholders, and how can they leverage the benefits and insights activists can provide?

Activist campaigns

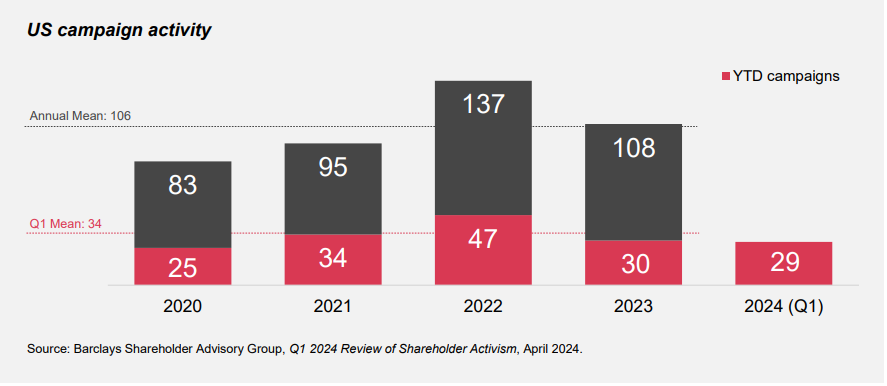

The number of activist campaigns reached a recent high in 2022, with shareholders launching 137 campaigns in the US. That represents a return to pre-pandemic levels following a significant decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Activity through the first quarter of 2024 suggests that the rebound will hold. Proxy contests have rebounded too after the lull that followed the SEC’s universal proxy rule becoming effective in August 2022.

Changes related to mergers and acquisitions have historically been among the top objectives of an activist campaign. This could mean pushing a company to sell all or part of itself, or to seek better terms if it’s already in talks to be acquired. These kinds of outcomes remained among activists’ most common goals in recent years. But the objectives of campaigns have shifted to reflect the changing deals landscape. As the pace of dealmaking slowed, campaigns were more likely to be centered on calls to break up the company. Questions remain about how the split among objectives will play out against the backdrop of a recovering M&A market.

Universal proxy and disclosure developments

August 2022 marked the start of a new era of proxy contests as the SEC’s “universal proxy” went into effect. Now, in a contested director election, parties must issue one universal proxy card listing all available candidates. The rule change allows investors to easily pick and choose which combination of candidates to vote for on one proxy card, rather than limiting the choice to the candidates on either the company’s or the dissident shareholder’s proxy cards.

It is still too early to fully understand the impact of the universal proxy rule. Unsurprisingly, the uncertainty the rule created about proxy fight outcomes led both activists and companies to prefer reaching a settlement agreement over taking a campaign to a fight in the year following the rule’s effective date. Through the first half of the second year, however, both sides seem more willing to test how proxy fights will play out under the new rule. Some had speculated that the universal proxy rules would make it easier for activists to gain board seats. However, early evidence suggests that proxy fight outcomes will mirror the pre-universal proxy pattern; investors will continue to support the side that makes the best case for the company’s long-term success.

Other SEC changes — to the ownership disclosure requirements — took effect in February 2024. The changes mean that investors must notify the market sooner if their ownership level crosses 5%. For Schedule 13D filers, those seeking to influence strategy, the deadline was shortened from 10 days to 5 days and the timing to make material updates from “promptly” to two days. It also clarifies the scope of derivatives that should be disclosed. Earlier notice of an increased equity stake (and possible takeover attempt) could give companies more time to consider and formulate a response. It could also make it harder for investors to accumulate a substantial position, as the stock price typically rises when there is a filing that indicates an activist intent.

Environmental and social in focus

Environmental and social matters have become a key priority for investors. For many of the large asset managers, these matters are a significant driver of their engagement work and priorities. These investors push companies for greater public disclosure on these topics, and many support shareholder proposals asking companies to make changes in these areas.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) is a familiar way to refer to these topics. However, this guide refers to environmental and social matters, and the governance thereof, independently of corporate governance matters. Corporate governance matters have a longer history in activism and are on a different trajectory from environmental and social issues, as we highlight in the shareholder proposal section. Directors should be careful not to conflate these matters.

Environmental and social matters generally play a secondary, albeit important role for hedge fund activists. In some cases, these issues are among several identified by the activist and specifically called out as an area for improvement. In limited cases, environmental or social issues are more fundamental to the campaign. A campaign could involve demands to spin off or close certain carbon-intensive businesses, shift company strategy toward renewable energy and products, or address workforce related concerns. Some of these fights are waged by funds with an environmental or social objective, while others are led by traditional activists.

Part II: Long-term view

Activists: who they are and what they want

An asset manager overseeing trillions of dollars in securities pledges to vote against the boards of companies that fall short on corporate governance as well as environmental and social matters. A hedge fund a fraction of that size threatens a proxy fight at a company it feels has too much cash on the balance sheet. Both fall under the umbrella of shareholder activism: seeking change because they think management isn’t maximizing their targets’ potential. But while they may share an ultimate goal, their tactics can differ greatly.

Institutional investors

Pension funds, insurance companies, and firms that manage mutual funds and exchange traded funds are all examples of institutional investors. Not only do institutional investors own a larger proportion of publicly traded companies’ shares than retail investors do, but they also vote their shares at a much higher rate. This makes them influential stakeholders for many public companies.

Institutional investors are normally long-term shareholders. Many benchmark their holdings to broad stock market indexes like the S&P 500. Others offer index funds to retail investors, who are attracted by their low fees. Passive funds can’t just sell a position if they think a stock is underperforming, or if they believe the company’s governance practices hinder its long-term value. Activism is one of the only levers they have to address these concerns. Through activism, they can bring attention to their concerns and drive the change that they believe will create long-term value — including through changes in corporate governance practices. The largest asset managers are vocal about their belief that companies with strong corporate governance practices can deliver better value in the long run.

Hedge funds

Hedge funds attract big dollars from investors seeking above-average returns. So, they are always looking for untapped value. Hedge fund activists often see that untapped value in the way a company is run or the strategy it pursues. They see ineffective management, a stale board or a company missing out on new opportunities. They see the potential for a new capital allocation strategy or changes in operations that will increase share value. And when their efforts to engage with executives or directors about these ideas fail, they often try to get board representation to help achieve their goals.

Hedge fund activists traditionally focused on capital allocation issues, such as dividends and share buybacks. Many then began looking for company combinations and break-ups — mergers, carve outs and spin-offs. Now there is a greater focus on operational activism, which has more of a long-term focus. Activists join the board (or appoint independent directors), replace members of management and help execute a new strategy. While many hedge funds had been thought of as being too focused on short-term gains, the longer-term operational activism has helped to shift that perception somewhat.

Other investors

Traditional asset managers and hedge funds account for most activist activity. And because they manage the most money — and vote the most shares — they have the greatest ability to make a serious push for change. But they aren’t the only shareholder activists.

Religious groups, nonprofits and other advocacy organizations also use the tools of shareholder activism, most notably shareholder proposals, to encourage companies to change. Investor coalitions formed around specific issues — ranging from climate action to corporate responsibility to requests for companies not to adopt diversity policies — are also growing in size and influence.

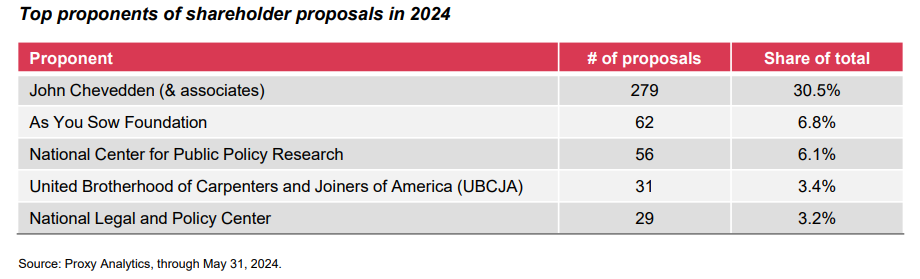

There are also a small handful of individuals who have made a name for themselves as activist shareholders through retail investing. In fact, these shareholders are responsible for a majority of all shareholder proposals that go to a vote each proxy season. Historically, they have tended to focus on “good governance” matters — majority-vote director elections, declassified boards and so on. Recently they have broadened their strategy to include ESG and other matters as well.

Part II: Long-term view

Tactics: how activists pursue their goals

Some shareholders turn to activism because they feel it’s an effective way to increase the value of the companies whose stock they own. Others do so to address governance practices they believe are hurting long-term value. Or they take issue with the company’s products or business practices. Activism can take many forms. But the goal is the same: to motivate management and boards to make changes in the way their companies are run.

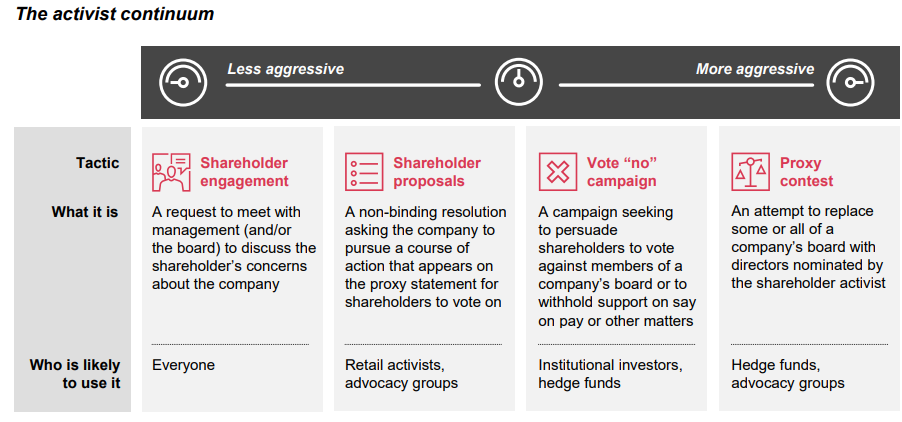

The tactics that shareholders use will depend on their objectives. What makes sense for an institutional investor with a long time horizon may not work for a hedge fund looking for a quicker return. You might even think about activist tactics as a continuum that begins with routine shareholder engagement. Not every request to meet with management is a prelude to more drastic forms of activism. But many shareholders who seek change will start by attempting to persuade. Others are more likely to start at the more aggressive end of the activist spectrum.

Shareholder proposals

In some cases, investors view a shareholder proposal as a way to begin the conversation with a company. Other times, institutional and retail investors submit — or threaten to submit — a shareholder proposal if direct engagement with the company and its directors doesn’t produce changes. Proposals can even be used as tools by labor unions. There, a union shareholder files a proposal that may act as a bargaining chip in its contract negotiations with the company.

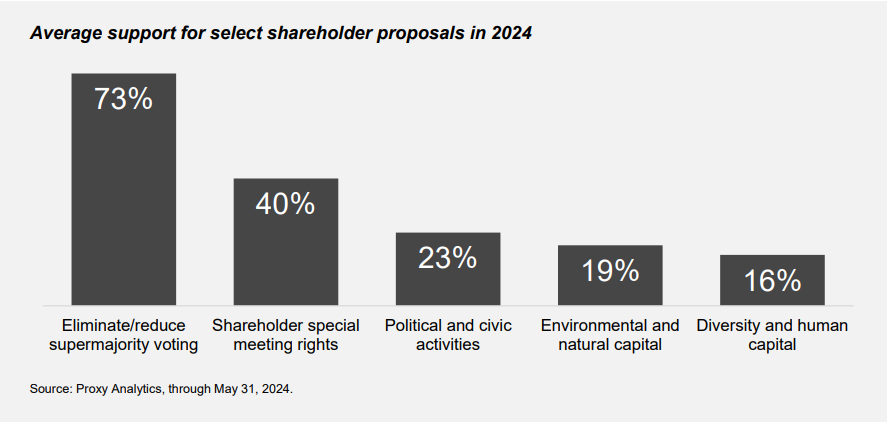

These proposals often focus on governance practices or policies, executive compensation, or the company’s behavior as a corporate citizen. Proposals both supporting and opposing a company’s adoption of environmental and social policies in particular have become much more common in recent years. Traditionally, proponents watch how the major institutional investors are voting on issues and have a sense of which shareholders may be likely to support their proposal going in.

A recent tactic is for a proponent to file a proposal even if it is unlikely to pass to draw attention to a specific issue or to encourage market dialogue on a topic. This is one reason why support for environmental and social related proposals is lagging behind corporate governance proposals. Another is that overall disclosure of environmental and social matters has improved in recent years, fueled in part by ongoing activism.

Vote “no” campaigns

Vote “no” campaigns urge shareholders to vote against (or withhold their votes from) director candidates or other matters such as say on pay. Vote “no” campaigns can send a strong signal about shifting shareholder priorities.

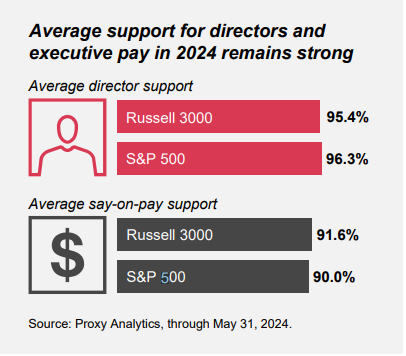

The vote doesn’t actually have to fail for a vote “no” campaign to achieve results. Overall shareholder support both for directors and for say on pay is typically above 90%. So, if support levels fall to the 60s or 70s, it sends a stark message about shareholder dissatisfaction. It also generates media scrutiny and can affect a director’s reputation. Directors often serve on multiple boards, and low support levels at one company can affect how that director is viewed at his or her other companies as well.

Proxy fights

Shareholder activists may conclude that the best way to achieve their goals is to replace some or all of a company’s board. In that case, they advance their own slate of director candidates and try to persuade other shareholders to vote for them. Proxy contests can be expensive and controversial. Historically, they’ve been most closely associated with activist hedge funds, but advocacy groups have been testing their usefulness under the new universal proxy rules.

The precise activism playbook may vary from investor to investor, but there are several steps hedge funds commonly take to make the threat of a proxy fight more credible. They may try to win the support of a company’s other shareholders by circulating a lengthy white paper that lays out the case for the changes they’d like to see. Or they may publish an open letter to the company’s management or board listing their concerns. It’s a virtual certainty that documents like these will end up in the hands of the media, further ratcheting up the pressure.

Proxy fights are long, expensive and draining for a company. Success isn’t assured for the hedge fund, either. That’s why activists and the companies they target frequently reach a settlement that heads off a full-blown proxy contest. As a result, the activist may receive seats on the company’s board or assurances from management that some of the changes it seeks will be enacted. Observers will be keenly interested in whether the August 2022 universal proxy rules (as discussed on page four) impact the balance between proxy fights and settlements.

Some institutional investors have expressed concern that companies are settling too easily. Before rushing to settle, they urge companies to at least reach out to their significant shareholders to solicit their views. Sometimes these investors agree with the activist — and sometimes they want the company to hold their ground against the activist.

Part II: Long-term view

Risk factors: the red flags that can lure activists

Every shareholder activist has a unique agenda. But history shows that companies that attract activist engagement tend to have some issues in common. Poor performance in the stock market, weak earnings compared to peers, governance missteps, and lack of attention to environmental and social matters can all trigger shareholder activism.

Poor financial or share performance

Shareholders are rarely happy to see a company underperforming its peers, hanging on to divisions that don’t fit with the rest of its business, or hoarding too much cash on a balance sheet. Whether they turn to activism as a result often depends on their investment strategy. The chances also tick up if there are other governance concerns.

Hedge fund activists are typically looking to unlock value they believe is going unrealized. Companies with a low ratio of market value to book value, excessive cash on hand or lots of monetizable assets like real estate may fall into their crosshairs. Institutional investors are commonly less likely to support activism at a company unless it also suffers from one or more of the governance weaknesses.

Governance weaknesses

Governance problems can both indicate other weaknesses at a company and can have a detrimental effect on its value. Issues that may prompt investors to engage with a company, to submit a shareholder proposal or take even more drastic measures may include:

- Board structure and composition. Many institutional investors are intensely focused on board composition, including board diversity. Companies with practices that make it difficult to vote out underperforming directors may also draw the ire of shareholders. These may include:

- Classified boards

- Election of directors by plurality vote

- “Zombie directors” who remain on the board after failing to receive majority support Even absent these structural issues, some shareholders will engage with companies around board tenure and refreshment.

- Shareholder rights. The inability for shareholders to call special meetings or take action by written consent commonly spark shareholder proposals and could draw extra attention to the company’s shareholder rights (or lack thereof).

- Executive compensation. Companies with problematic pay practices, pay that is out of alignment with company performance or that don’t respond after a low say-on-pay vote can all become targets of shareholder activism.

- Material weakness. Less frequently, disclosure of a material weakness can sometimes prompt shareholders to vote against audit committee members. It’s especially likely if the company is not seen to be taking appropriate action to remediate the issue.

Environmental and social shortcomings

Perceived poor practices on environmental and/or social risk and opportunities can also make a company an activist target. Environmental issues include lack of disclosure of risks related to climate change and management of plastic waste. Social responsibility considerations like inadequate labor, health or safety practices may also feature prominently. Activists also focus on the alignment of political spending and lobbying with a company’s public environmental and social policies.

Many of the largest asset managers have called for more disclosure in this area. They want companies to discuss how issues such as climate change and D&I factor into their strategies. And they want to know companies’ plans for confronting those challenges.

Hedge funds may also focus on environmental and social issues as factors that can boost the relevance of their activist campaigns with other shareholders, especially when they can demonstrate a link between the issue and shareholder value. In rare cases, the primary concern being addressed may be environmental or social.

78%of investors in the US market agree that companies should embed ESG directly into corporate strategy.

Source: PwC’s Global Investor Survey 2023

Base: 128 US investors

Ignoring shareholder concerns

Lack of responsiveness to investors can bring unwelcome attention. Sometimes an issue that has come up during shareholder engagement may evolve into a shareholder proposal. Other times, if the company hasn’t acted in response to a concern, the consequences can be more severe. For example, if a company’s say-on-pay vote garners low support levels, shareholders expect to see changes in the company’s incentive plans. If those changes don’t come, shareholders may launch a vote “no” campaign targeting the directors on the compensation committee. The bottom line: It rarely hurts to hear a shareholder out, determine whether their arguments have merit and, if so, consider acting in response.

Part II: Long-term view

Heading off an activist

Shareholder activism can come as a surprise. When a hedge fund presses a company to divest an underperforming asset or put itself up for sale, it can leave the management team and board scrambling. They may ask themselves why they didn’t see it coming. Even being on the receiving end of a shareholder proposal can feel like an unwelcome intrusion.

Directors have a key role to play in being prepared. They can anticipate which activists may engage with the company, the issues they may raise and how other shareholders might respond. They can push management to address issues that may attract activist attention. Not only can these actions help ward off an activist, but they may also help improve the company’s performance and its relationship with key stakeholders. And when an activist does come calling, the board can help the company find constructive ways to respond and leverage the interaction.

Take a candid look at your company

Directors should always make it their business to stay informed about their company’s strategy and how effectively it’s being executed. This requires looking at the company’s performance with a critical eye. However, the data directors get can sometimes be so granular that it’s hard to see the big picture. Other times, it might be so high level that important details are easily overlooked.

Focusing on common triggers for activist engagement may help boards cut through the noise. Asking how the company’s corporate governance as well as environmental and social disclosures compare to best practices, for example, or how the dividend stacks up against peers that have been targeted by activists may help bring clarity. Ask to hear from outside experts, industry analysts, investment bankers or others from outside the company to get a better understanding of how the company is seen by investors and potential activists. Make sure to ask for outsiders’ “unvarnished” views — ones that haven’t been toned down (or whitewashed by management).

If there are issues, take proactive steps to address them. This can reduce the chance of becoming an activist target. It can also strengthen your credibility with the company’s shareholders. Even if the company chooses not to make any changes, going through the critical process will help company executives and directors reaffirm and articulate why they believe the company is on the right course.

Know your shareholders

Ensure that the board is informed when an activist takes a significant position in the company or in an industry competitor. And make sure the board hears about broader activism trends that could affect the company in the future. Understanding what these shareholders may seek will help the company assess its risk of becoming a target and help it know what tactics to expect.

And of course, directors should keep up to date on the views of the company’s largest shareholders. This includes carefully watching any changes to their public engagement priorities or proxy voting agendas.

Create an engagement plan

Once a company identifies areas that may attract activist attention, engaging with other shareholders on these topics can help prepare for — and in some cases may help to avoid — an activist campaign. Being transparent about the company’s vulnerabilities and its strategic choices can help change a shareholder’s view of the issue and demonstrate that the board is fulfilling its oversight responsibilities. Even before the company receives an activist overture, some companies may find it helpful to start getting directors involved in discussions with major investors. If shareholder activists do target the company, directors will already have credibility with other investors. That may make them more effective spokespeople for the company’s position.

Part II: Long-term view

How to respond to an activist

When an activist comes calling, the company response is critical. An ineffective response may make things worse by giving the impression that the company’s management and board are not attuned to shareholder concerns. While the activist’s scrutiny may be unwelcome, that doesn’t mean their concerns are without merit. An encounter with a shareholder activist can make the company stronger in the long run — if it’s handled effectively.

Objectively consider the issues on the table

Hedge fund activists usually do extensive homework before they approach a company. Based on that research, they develop specific proposals for unlocking value — at least in the short term. And they have often discussed these ideas with other shareholders. Assume the company’s institutional investors have already spent time evaluating the activist’s suggestions. Investors will expect the company’s executives and board to do the same — even when it’s uncomfortable. And it often is. They might be looking for changes in the boardroom, which may feel like a personal affront to the directors around the table. Or they may be looking for a change in management, which will almost certainly feel like an attack on the CEO. But none of these ideas should be dismissed out of hand.

It’s also important to take a shareholder proposal or vote “no” campaign seriously. Take a step back. Few companies are perfect when it comes to corporate governance. Perhaps the company’s practices are justified. But are there areas that could be improved? Are there changes that were avoided as a result of status quo bias? If that’s the case, shareholder pressure could be a valuable wakeup call — if it isn’t ignored.

Determine how best to respond to the investor

When it comes to hedge fund activists, the strategy may differ. If the fund approaches privately, it may make sense to respond in writing or hold a meeting. This gives the company a chance to hear about the activist’s criticisms. It may also lay the groundwork for future private conversations — which can be helpful if the company later wants to negotiate a settlement with the activist. When hedge fund activists take their campaigns public, however, the smartest move may be to say very little. There’s very little potential benefit for a company in trading blows with a hedge fund activist in the media. And in the case of a proxy fight, some of the individuals in question may ultimately become peers in the boardroom, so playing the long game when it comes to the relationship is vital.

For companies that have received a shareholder proposal or been targeted for a vote “no” campaign, their best bet is to reach out to the investor and discuss their specific concerns. When dealing with a shareholder proposal, the company and the shareholder may be able to agree on some action at the company in exchange for withdrawing the proposal. Shareholders don’t always insist on immediate action. They know change can take time, and often they are satisfied if the company demonstrates that it has a plan in place to address the issue. Communication might not put an end to a vote “no” campaign, but understanding the shareholder’s perspective will help the company respond. In many cases, when management or the board engages with other shareholders, they will ask about the company’s relationship with the activist.

Reach out to other shareholders

When activists are contemplating vote “no” campaigns or proxy fights, they will need support from other shareholders to be effective. It’s safe to assume they’re already engaging with the company’s other investors, so it’s important that management and the board make themselves heard as well. An approach from an activist can present an opportunity to discuss the issues they raise with other shareholders. Take the chance to articulate the company’s view about why its current course is in the best long-term interests of the company and all of its investors (if it is).

Ideally, the company already has an established relationship with those shareholders to build upon. If the company doesn’t believe the activist’s proposed changes are in its best long-term interests, investors will want to know why — and just as importantly, how the company reached this conclusion. On the other hand, if the company has decided to make some changes, be open about what those are. And consider disclosing the breadth of the company’s shareholder engagement efforts in the proxy statement to give yourself credit for your outreach. Often, we hear that the suggestions activists make are ones that the company has already been considering.

Look for ways to build consensus

More companies than ever are finding ways to work with activists. Proxy contests are costly and time consuming. It may make sense to find common ground with shareholder activists to take these risks off the table.

Reaching an agreement with a shareholder activist may require the company to increase disclosure of certain information, change its capital allocation, or even add new directors to the board. These moves may not have been in the company’s plans before the activist encounter, but they may make sense if the alternatives include even more drastic changes — such as a proxy fight that could give the activist control of the board.

Activists are also motivated to reach agreement. Even though target companies typically spend many times as much on proxy solicitation efforts, the cost to an activist is also significant. If given the option, most activists would prefer to spend less time and money to achieve their goals. Once they agree, the activist and the company enter into a standstill agreement that sets the terms of their relationship going forward.

Even non-binding shareholder proposals can cause embarrassment if they pass — or even just receive unwanted media attention. It may make sense to see if there’s a middle ground between the company and the proponent that both can live with.

Conclusion

Even as activism — by institutional investors, hedge funds and others — continues at a healthy pace, many think the number of campaigns still could be on the upswing. For companies, listening and being prepared are crucial. Boards have an important role to play in helping to navigate the changing landscape of shareholder activism.

Print

Print