The following post comes to us from Joseph Warin, partner and chair of the litigation department at the Washington D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, and is based on a Gibson Dunn client alert by Mr. Warin and Jeremy Joseph. The full publication, including footnotes and appendix, is available here.

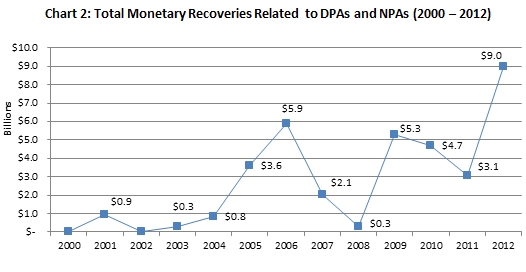

“Over the last decade, DPAs [Deferred Prosecution Agreements] have become a mainstay of white collar criminal law enforcement,” Lanny Breuer, the head of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, declared on September 13, 2012. Corporate Deferred Prosecution Agreements (“DPAs”) and Non-Prosecution Agreements (“NPAs”) (collectively, “agreements”) have, in Mr. Breuer’s words, ameliorated the “stark choice” that prosecutors faced: either to employ “the blunt instrument of criminal indictment” that he likened to using “a sledgehammer to crack a nut” or to “walk away” and decline prosecution outright. Mr. Breuer declared that DPAs and NPAs “have had a truly transformative effect on . . . corporate culture across the globe” resulting in “unequivocally[] far greater accountability for corporate wrongdoing–and a sea change in corporate compliance efforts.” Mr. Breuer’s comments are timely, coming in a year during which such agreements yielded a record level of monetary penalties and related payments totaling nearly $9.0 billion and are increasingly used to resolve front-page criminal matters.

This client alert, the ninth in our series of biannual updates on DPAs and NPAs, (1) summarizes the DPAs and NPAs from 2012, (2) considers detailed remarks from leading enforcement officials with the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) regarding settlement agreements, (3) examines compliance measures presented in recent non-FCPA agreements as examples of DOJ-endorsed good practices in various industries, and (4) looks across the Atlantic to evaluate the United Kingdom’s prospective use of DPAs.

DPAs and NPAs in 2012

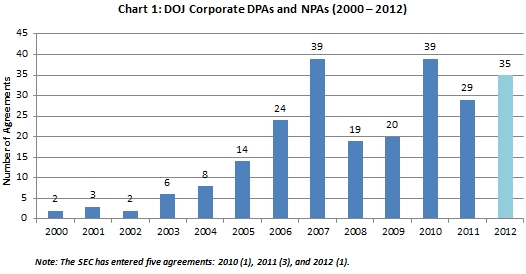

The headline for 2012 is both the near-record pace of DOJ DPAs and NPAs and the eye-popping $9.0 billion dollars in monetary amounts obtained by the U.S. government related to settlements involving a DPA or NPA. Federal enforcement agencies in 2012 continued to demonstrate increasing use of DPAs and NPAs, entering into 36 agreements. DOJ entered 35 agreements: 19 DPAs and 16 NPAs, and the SEC entered 1 DPA. That total approaches the record of 40 agreements (39 by DOJ and 1 by the SEC) set in 2010. Chart 1 reflects agreements that DOJ entered in 2012, and the note reflects that the SEC has entered five since its adoption of such agreements in 2010. These charts are derived from a Gibson Dunn database that contains details of all 245 corporate settlement agreements between 2000 and 2012.

As Chart 2 depicts, this year’s $9.0 billion in settlement payments eclipses the previous record, set in 2006, by more than $3.1 billion. This year, nine agreements involved monetary settlements of $100 million or more, with the average total settlement value at approximately $250 million per agreement. Notable among the settlements were three agreements topping out at more than $1 billion, plus two other agreements with totals of more than $500 million each.

DOJ and SEC Officials Comment on DPAs and NPAs

Senior DOJ and SEC officials undertook a concerted effort this year to better inform companies, the legal community, and the public about DPAs and NPAs. Because some corporate gadflies have criticized corporate settlement agreements as weak punishment compared to criminal indictments, efforts by senior officials to discuss their increasing use of DPAs and NPAs advance the public understanding of the basis, purpose, and value of these agreements. Moreover, the discussion of agreements yields valuable information for companies anticipating settlement discussions with DOJ and/or the SEC.

Insight and Guidance from the Head of DOJ’s Criminal Division

The head of DOJ’s Criminal Division, Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer, offered a spirited defense of the benefits of DPAs and NPAs in a speech to the New York City Bar Association on September 13, 2012. As noted in the introduction, Mr. Breuer declared that DOJ’s growing use of DPAs and NPAs has had “a truly transformative effect on particular companies, and, more generally, on corporate culture across the globe.” Prior to the early 1990s, he explained, prosecutors investigating corporate wrongdoing could “either indict, or walk away.” Since then, the development of DPAs and NPAs has produced “unequivocally, far greater accountability for corporate wrongdoing–and a sea change in corporate compliance efforts,” Mr. Breuer said. While a DPA or NPA can help a company potentially avoid the “disaster scenario of an indictment,” a company agreeing to a DPA or NPA must “almost always . . . acknowledge wrongdoing, agree to cooperate with the government’s investigation, pay a fine, agree to improve its compliance program, and agree to face prosecution if it fails to satisfy the terms of the agreement,” Mr. Breuer said. Gibson Dunn’s F. Joseph Warin and Mr. Breuer, when in private practice, jointly negotiated the DOJ Fraud Section’s first DPA in 2001. In any case, with the rise of DPAs and NPAs, Mr. Breuer believes that “companies know that they are now much more likely to face punishment” and, “[o]verall, this state of affairs is better for companies, better for the government, and better for the American people.”

Mr. Breuer’s prepared remarks and his candid comments in the question-and-answer session that followed provide worthwhile guidance to companies entering into negotiations with the DOJ Criminal Division:

- To avoid indictment, companies “must prove to us that they are serious about compliance. Our prosecutors are sophisticated. They know the difference between a real compliance program and a make-believe one[,] . . . between actual cooperation with a government investigation and make-believe cooperation[, a]nd . . . between a rogue employee and a rotten corporation.” In Mr. Breuer’s view, a DPA or NPA “may be the best resolution” in cases where a “company has gone to extraordinary lengths to turn itself around, for example, or provided the government with extensive cooperation.”

- The Criminal Division does not “take lightly” the decision to prosecute a company. Mr. Breuer explained that the collateral consequences of prosecution “in white collar crime cases [] literally keep [him] up at night” and must be considered as part of “responsible enforcement.” Those collateral consequences include “the effect of an indictment on innocent employees and shareholders” balanced against “the nature of the crimes committed and the pervasiveness of the misconduct,” Mr. Breuer noted. “I personally feel that it’s my duty to consider whether individual employees with no responsibility for, or knowledge of, misconduct committed by others in the same company are going to lose their livelihood if we indict the corporation,” he explained and noted two examples: “In large multi-national companies, the jobs of tens of thousands of employees can be at stake. And, in some cases, the health of an industry or the markets are a real factor.”

- Mr. Breuer reported that and his staff are “frequently on the receiving end of presentations from defense counsel, CEOs, and economists who argue that the collateral consequences of an indictment would be devastating for their client.” He added, “In my conference room, over the years, I have heard sober predictions that a company or bank might fail if we indict, that innocent employees could lose their jobs, that entire industries may be affected, and even that global markets will feel the effects. Sometimes–though, let me stress, not always–these presentations are compelling.”

- Companies should not begin their negotiations with DOJ by “demanding [a DPA or NPA] on day one,” Mr. Breuer explained. He further cautioned that it is “probably not one of the best strategies” for a sophisticated company to immediately inform Breuer’s staff that it wants a DPA. Instead, a company that seeks a DPA should earn it by asking how it can best cooperate, by addressing the issue that DOJ has targeted, and demonstrating its recognition that serious issues exist.

- Mr. Breuer confirmed that there is “no one-size-fits-all approach” to the compliance controls in DPAs and NPAs. With regard to the negotiation and implementation of compliance controls in agreements, Mr. Breuer said that companies receive a “fair bit of oversight” from DOJ in evaluating their compliance programs and that DOJ looks to the compliance standards in the industry to evaluate the adequacy of the proposed controls. For example, if a company operates in a highly regulated industry with a robust regulator, it may not need a monitor–particularly where the company has reformed itself and the regulator is properly resourced to fulfill its duties. Conversely, if DOJ identifies a systemic problem within the company but nonetheless believes that the company has cooperated with the government investigation, Breuer explained, DOJ may offer the company a DPA but require it to engage a monitor–especially when the industry lacks a strong regulator. Overall, Mr. Breuer noted “a very rigorous and robust give and take” between DOJ and the company to determine the agreement’s requirements regarding monitoring and reporting.

Mr. Breuer also took the opportunity to answer some of the criticism of DPAs and NPAs by some skeptics in recent years:

- Responding to the shibboleth that DPAs and NPAs are weak substitutes for indictment, Mr. Breuer explained, “in many ways, a DPA [or NPA] has the same punitive, deterrent, and rehabilitative effect as a guilty plea” and went on to note the similarities. Further, he noted, “Perhaps most important, . . . the company must virtually always publicly acknowledge its wrongdoing . . . in detail. This often has significant consequences for the corporation.”

- Noting a concern regarding a lack of uniformity among criminal resolutions using DPAs and NPAs, Mr. Breuer responded that U.S. Attorneys’ Offices and other DOJ units that use them “try as best as they can” to apply objective criteria. Most DPA and NPA negotiations originate from only a few DOJ entities, which “in and of itself creates some level of uniformity,” he said.

- Addressing another often repeated criticism that DPAs and NPAs somehow undermine individual punishment, Mr. Breuer cited some recent individual convictions explaining that, “individual wrongdoers can never secure immunity through the corporate resolution.” In a subsequent speech on October 23, 2012, Mr. Breuer added, “[a]s I have said repeatedly, the strongest deterrent against corporate wrongdoing is the prospect of prison time. That is why I have put such a high priority on making sure that individuals are prosecuted when the evidence warrants prosecution.”

SEC Seeks Consistency with DOJ

Another top U.S. regulator, the director of the SEC’s Enforcement Division, Robert Khuzami, said that although the Commission has not used many DPAs and NPAs since their adoption by the Commission in 2010, its goal over time is to increase the use of these tools to “dovetail more nicely” with DOJ agreements. Mr. Khuzami noted that “more uniformity of use” of the agreements by both DOJ and the SEC will result in more “consistency and clarity for the regulated community.” In the only case to date in which both DOJ and the SEC entered into a DPA and/or NPA for the same matter, the cases were resolved differently: Tenaris S.A. resolved FCPA charges with DOJ through an NPA and with the SEC through a DPA. The outcome reflected different charging considerations by each agency.

Furthermore, in early 2012, Mr. Khuzami announced a policy change intended to better harmonize SEC civil settlements with DOJ criminal resolutions. Previously, a defendant could admit to criminal conduct in a plea or through a DPA or NPA and concurrently settle parallel SEC charges on a “neither admit nor deny” basis, i.e., without admitting or denying civil liability. The new policy, however, provides that when a defendant faces a criminal conviction, or a DPA or NPA that includes admissions of criminal conduct, the SEC will require admissions in its civil settlement.

Joint DOJ/SEC FCPA Resource Guide

On November 14, 2012, DOJ and the SEC issued a long-awaited, joint publication titled, A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (the “Resource Guide”). Our November 19, 2012, Client Alert summarized the Resource Guide’s collection of useful information for corporate executives, compliance officers, and attorneys. In addition to its comprehensive FCPA guidance, the Resource Guide offers additional, high-level insight into each agency’s approach to resolving investigations–including the use of DPAs and NPAs. For example, the Resource Guide emphasizes the importance that DOJ and SEC officials place on the “adequacy of a company’s compliance program,” noting that the adequacy of such a program “may influence whether or not charges should be resolved through a [DPA] or [NPA]” as well as the “appropriate” duration of any such agreement, “the penalty amount,” or “the need for a monitor or self-reporting.”

On November 15, 2012, Charles Duross, chief of DOJ’s FCPA unit, speaking before the American Conference Institute’s 28th National Conference on the FCPA, cited the value of self-disclosure in the DOJ’s decision to enter into a DPA rather than a guilty plea. Citing DOJ’s recent FCPA settlement with aviation company BizJet International Sales and Support, Inc., Mr. Duross noted that, but for BizJet’s voluntary disclosure of FCPA issues, DOJ “wouldn’t have known about the conduct. And it was bad conduct.” The FCPA Unit concluded, however, that “while . . . we would have been entirely within our rights to . . . require a guilty plea,” “we want to reward the company in a meaningful way for having done something that we thought was the right thing to do.” That “reward” was a DPA and, he said, foregoing the imposition of a compliance monitor.

In sum, these comments from Messrs. Breuer, Khuzami, and Duross provide companies with invaluable guidance when considering settlement strategies to avoid indictment and negotiating DPAs or NPAs.

Focus on Trade Sanctions DPAs and NPAs

Recent years have seen a dramatic uptick in prosecutions for violations of trade sanctions, export controls, and related regulations, along with a concurrent rise in penalties associated with such violations. Although DOJ entered no trade sanctions-related DPAs or NPAs from 2000 through 2006, the years since have marked the dawn of a new era for enforcement in this area. From 2007 through 2012, DOJ entered 13 agreements (11 DPAs and 2 NPAs) involving trade sanctions or export controls. The conduct alleged in these agreements covers violations of numerous laws and regulations, namely the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the Trading with the Enemy Act, and/or the Arms Export Control Act. These settlements frequently reflect transactions with entities in countries currently or formerly subject to U.S. economic sanctions, e.g., Cuba, Iran, Libya, Myanmar, and Sudan, prohibited under U.S. law and/or regulation. Prosecution in these cases often involves a multitude of law enforcement and regulatory agencies because investigation and enforcement authority is spread across the Executive Branch. DOJ entities involved in past cases have included the National Security Division, the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section of the Criminal Division (“AFMLS”), and various U.S. Attorney offices around the country. Other agencies involved include the U.S. Department of the Treasury through its Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”), and/or the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”). Export controls cases typically involve the U.S. Department of State. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security was involved in at least one case.

|

Table 1: Trade Sanctions DPAs/NPAs (2000 – 2012) |

||

|

Company |

Year |

Monetary Recoveries |

| ITT Corp. |

2007 |

$100,000,000 |

| Credit Suisse |

2009 |

$536,000,000 |

| Lloyds TSB Bank |

2009 |

$350,000,000 |

| ABN Amro Bank N.V. |

2010 |

$500,000,000 |

| Barclays Bank |

2010 |

$298,000,000 |

| PPG Industries |

2010 |

$2,032,319 |

| Sirchie Acquisition Co., LLC |

2010 |

$12,600,000 |

| ACADEMI LLC |

2012 |

$7,500,000 |

| Essie Cosmetics LTD |

2012 |

$450,000 |

| HSBC Bank USA, N.A. and HSBC Holdings plc |

2012 |

$1,921,000,000 |

| ING Bank, N.V. |

2012 |

$619,000,000 |

| Standard Chartered Bank |

2012 |

$327,000,000 |

| United Technologies Corp. |

2012 |

$75,700,000 |

|

TOTAL |

$4,749,282,319 |

|

As Table 1 indicates, although the first DPA involving trade sanctions issues was entered in 2007, the marked increase in this type of prosecution began in 2010, when DOJ entered four such agreements. In 2012, DOJ entered six agreements concerning allegations of trade sanctions or export controls violations.

Of the 13 agreements in this category, more than half have involved financial institutions. One long-running investigation has produced multiple settlements in connection with allegations that various banks conducted transactions involving customers subject to U.S. sanctions. That investigation has been a joint effort between DOJ AFMLS and the New York County District Attorney’s Office (“DANY”), which is responsible for New York State prosecutions in Manhattan and includes special units dedicated to prosecuting white collar crime. In 2012, several banks entered DPAs with DOJ AFMLS, as well as other federal regulators and DANY, resolving allegations that they conducted transactions with sanctioned entities. These recent agreements resulted in monetary penalties and related settlements approaching $3 billion. Other prosecutions have involved companies whose businesses and products run the gamut from nail polish, to the oil and gas sector, to defense technology, and to private military contractors.

Compliance Measures in Recent DPAs and NPAs: Road Maps to Compliance Good Practices

Make no mistake: while not formally labeled as such, DOJ and other regulators appear to be promulgating compliance guidance for various industries through the remedial requirements included in the DPAs and NPAs used to resolve real-world cases. These settlements reflect DOJ’s and other regulators’ perspective of compliance good practices for a given industry. Since DPAs and NPAs now cover a broad spectrum of enforcement matters, they are valuable resources for companies to consider when implementing and revising compliance policies and procedures. As Mr. Breuer’s September 2012 remarks and the FCPA Resource Guide state, corporate resources dedicated to an adequate compliance program can help prevent serious issues from arising and may militate against a criminal guilty plea if they do occur. Several agreements from 2012 offer valuable insights into the government’s compliance expectations in the areas of trade sanctions, Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”), anti-money laundering (“AML”) and consumer financial transactions, anti-fraud measures, compliance officer reporting structures, and supply-chain management.

Compliance Measures: Anti-Money Laundering and Trade Sanctions

In December 2012, HSBC Bank USA, N.A. (“HSBC Bank USA” or the “Bank”) and HSBC Holdings plc (collectively, “HSBC”) entered into a DPA with the Criminal Division to settle allegations that HSBC Bank USA violated the BSA by failing to maintain an effective AML program and not conducting appropriate due diligence on various foreign account holders and that HSBC Group affiliates allegedly conducted transactions that caused HSBC Bank USA and other U.S. financial institutions to process payments in the United States that violated U.S. trade sanctions. HSBC’s DPA recognized the extensive remedial actions taken by HSBC and HSBC’s agreement to continue to enhance its AML programs and OFAC compliance. These actions, as summarized below, set forth various sound industry practices relating to BSA, AML, and trade sanctions compliance.

- Resource Investment: Spending by HSBC Bank USA on staff allocated to AML compliance increased approximately nine-fold even before the entry of the DPA, and the Bank increased its number of AML compliance staffing nearly ten-fold. The Bank also adopted a new automated monitoring system that monitors every wire transaction moving through the institution.

- Organization of AML Compliance Department: HSBC Bank USA strengthened the compliance department’s reporting lines and elevated its status within the Bank by

(i) separating the Legal and Compliance departments, (ii) requiring that the AML compliance director report directly to the Chief Compliance Officer, and (iii) providing that the AML compliance director report directly to the Board and senior management about the status of the Bank’s BSA and AML compliance program on a regular basis. - Global Compliance Standards: HSBC Group’s remedial measures included adoption and implementation of global compliance standards, including applying the highest or most effective AML requirements for operations worldwide, and using OFAC’s and other sanctions lists to conduct screening in all jurisdictions and in all currencies.

- Global Responsibility for the Head of HSBC Group Compliance: HSBC Group centralized oversight of every compliance officer worldwide to ensure that both accountability and escalation flow directly to and from HSBC Group Compliance.

- Global Risk Management: The agreement identified a number of measures with regard to risk management, including implementing a new customer risk-rating methodology and the adoption of risk guidelines for considering business opportunities “in countries posing a particularly high corruption/rule of law risk” and limiting business in countries where there is a high risk of financial crime.

- Bonus Structure: HSBC Group changed its bonus structure for its senior executives to consider executives’ fulfillment of its compliance standards and values.

- Termination of Risky Business: HSBC Bank USA terminated certain business relationships and exited the Banknote business, and HSBC Group sold subsidiaries and withdrew from nine countries by applying “a more consistent global risk appetite.”

- Training and Procedures for Timely Notification of Red Flags: The agreement requires HSBC to implement specific procedures and training to ensure the compliance officers responsible for sanctions are promptly made aware of requests or attempts to withhold or change identifying information that may reflect an effort to evade U.S. sanctions laws.

- Due Diligence Requirements: The agreement requires HSBC to implement more robust risk-based AML and BSA procedures for conducting due diligence of potential new business entities in connection with mergers and acquisitions, including by involving audit, compliance, and legal personnel in the due diligence process.

Noteworthy among these provisions is the substantial compliance remediation efforts that HSBC performed prior to entering the DPA, including nearly ten-fold increases in compliance spending and staffing, exiting more than 100 business relationships for risk reasons, and undertaking a comprehensive overhaul of its compliance structure, controls, and procedures.

Compliance Measures: Anti-Money Laundering in Consumer Finance Context

In November 2012, MoneyGram International Inc., a global money transfer business that operates worldwide through numerous independently-owned outlets operated by agents, entered into a DPA with DOJ to resolve allegations that it failed to maintain an effective AML program and aided and abetted allegedly fraudulent consumer fraud schemes in which its agents allegedly were complicit. In assessing AML controls in the consumer finance context, in addition to considering the remedial actions taken by MoneyGram, the enhanced compliance requirements appended to MoneyGram’s DPA, discussed below, delineate key compliance measures designed to prevent consumer fraud schemes by agents.

- Board-Level Oversight of Compliance: The company agreed to create an independent Compliance and Ethics Committee of the Board of Directors with direct oversight of the company’s Chief Compliance Officer and its anti-fraud and AML compliance programs.

- Executive Review and Bonus Structure: The agreement requires that the executive review and bonus system reward adherence to international compliance-related policies and procedures and U.S. laws and regulations. The new structure makes any executive who receives “[a] failing score in compliance . . . ineligible for any bonus for that year.” The agreement also requires the company to claw back bonuses given to executives if they are later determined to have contributed to “compliance failures.”

- Global Compliance Standards and Auditing: The company agreed to adopt and maintain uniform anti-fraud and AML standards for all of its agents worldwide. At a minimum, U.S. legal standards will apply unless the Financial Action Task Force interpretative guidance for money service businesses is stricter in any area. The company further agreed to design and implement a risk-based program to audit the agents’ compliance with the global standards.

- Agent Due Diligence Remediation: The agreement requires the company to design and implement a remediation plan to conduct risk-based due diligence on any agents worldwide based on objective criteria–whether the agent has had more than one fraud-related complaint in any 30-day period since 2009. Further, the agreement requires the company to adopt enhanced due diligence procedures for high-risk agents or agents operating in high-risk areas.

- Transaction Monitoring: The agreement calls for a risk-based program to verify the accuracy of information related to the sender and recipient of money transfers and to adopt an automated anti-fraud alert system that will ensure a review of the maximum number of transactions feasible.

- High Risk Countries: The agreement requires the assignment of at least one AML compliance officer to oversee compliance for each country designated as high risk for fraud or money laundering, the rationale being that the compliance officer will develop expertise over the risk issues presented in the country of responsibility.

- Reporting Requirements: The agreement requires specific, detailed reports to DOJ every 90 days with regard to an array of activities, including metrics and data related to consumer fraud complaints and explanations of the company’s responses. The agreement further requires monthly submissions of data to the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel Network related to any relevant fraud-related activity by its agents.

Among these provisions, the frequent reporting obligations and the requirement for a compliance officer dedicated to each and every country conveys the particular views of enforcement authorities on certain areas of compliance and fraud prevention.

Compliance Measures: Supply-Chain Management

In July 2012, Gibson Guitar Corporation entered an NPA with DOJ, including the Environmental Crimes Section, to resolve allegations that it improperly classified, for tariff purposes, imported ebony and rosewood used as fingerboard blanks on its guitars in violation of wildlife protection laws under the Lacey Act (16 U.S.C. § 3371 et seq.). As part of its settlement, Gibson Guitar submitted to a comprehensive Lacey Act compliance program that specifically addressed supply-chain issues and procurement systems. The NPA’s compliance provisions are noteworthy because it provides a possible framework for agreements in other contexts–such as trade sanctions, immigration, and FCPA cases–where supply chain and foreign procurement issues feature prominently. The NPA’s compliance requirements include the following measures.

- Annual Supply Chain Audits: The agreement requires the company to audit all documents, certifications, licenses, and other records associated with raw materials purchasing practices to “ensure compliance” with the company’s Lacey Act compliance program. The audit will make inquiries of foreign government agencies, third-party certifiers, non-profit organizations, and/or non-governmental organizations to assess changes in foreign forestry or export laws.

- Sourcing with Due Care: The compliance program explains that the Lacey Act requires companies to source raw materials with “due care.” The agreement goes on to specify a seven step process for Gibson Guitar employees to source raw materials consistent with U.S. law.

- Supply Chain Management Checklist: Of particular note is the inclusion of a highly detailed supply chain management checklist for employees to use containing questions the company should answer to establish that it exercised “due care” in ensuring proper supply chain management.

- Use of Collective Standards and Resources: The agreement endorses the company’s approach of using independent certification organizations, such as the Forest Stewardship Council, to validate the legality and sustainability of the suppliers’ practices. The agreement also identifies a number of watch lists and other resources from independent parties with information relevant to the company’s supply chain due diligence efforts to be used as a compliance reference.

- Validation of Foreign Legal Requirements: When entering new markets or using new suppliers, the agreement requires Gibson Guitar to make reasonable inquiries into the foreign laws governing the protection and export of raw materials from the country of origin through the foreign government or a local law firm, but not through the supplier itself.

- Records Retention: The agreement requires the company to retain all records associated with its Lacey Act compliance program for five years.

The company’s agreement to conduct annual supply chain audits to continually reassess its compliance with various U.S. and foreign environmental laws suggests that DOJ expects companies to have an active awareness of compliance issues deep into the capillaries of its supply chain.

Compliance Measures: Chief Compliance Officer Reporting Structures

In our mid-year update, we noted that DPAs and NPAs often provide specific guidance regarding internal reporting structures for the Chief Compliance Officer (“CCO”). Overall, DOJ’s Fraud Section regards CCOs who have a direct reporting line to a company’s Board of Directors as a hallmark of an effective compliance program and has indicated that such a structure may influence the DOJ’s decision not to prosecute FCPA cases. But DOJ does not prescribe any particular reporting structure. In prior DPAs, DOJ explained that the CCO “shall have direct reporting obligations” to the company’s audit committee or the appropriate committee of the board of directors. Underscoring the lack of a one-size-fits-all approach to compliance, an August 2012 DPA explained that “[t]he Chief Compliance and Risk Officer will have reporting obligations directly to the Chief Executive Officer and periodic reporting obligations to the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors.” Clearly DOJ approaches these reporting structures individually and demands, whatever the precise reporting structure, that it be effective.

In sum, careful scrutiny of these agreements as they are issued can help companies keep abreast of DOJ’s view of sound compliance practices and help companies benchmark their compliance programs. Doing so not only directly encourages the evaluation and adoption of emerging good practices, but their adoption, as appropriate, also can improve companies’ position with prosecutors and regulators if they do find themselves facing allegations of improper conduct.

United Kingdom Closes in on DPA Legislation Passage

The U.K. Government this year firmly came out in favor of adopting DPAs. During 2012, it made steady progress toward the enactment of legislation to permit its law enforcement agencies to employ DPAs to resolve criminal allegations against organizations. As we discussed in our 2012 Mid-Year Update, the U.K. Government opened a consultation period on the adoption of DPAs on May 17, 2012. On October 23, 2012, the Ministry of Justice The draft legislation on DPAs has been included in the larger Crime and Courts bill, which passed the House of Lords on December 18, 2012.

The U.K. Government received widespread support for its plan to introduce DPAs. Eighty-six percent of respondents to the consultation expressed support for DPAs in the prosecution of “economic crime.” Nearly half supported expanding the proposed DPA law to cover a more diverse range of criminal activity, including health and safety offenses and environmental offenses. For the time being, the U.K. Government has declined to expand the proposed scope of DPAs beyond certain economic crimes (fraud, bribery, and money laundering), but has indicated a willingness to reassess whether DPAs should be available for a larger range of offenses if they are seen to operate successfully for economic crimes. It has not escaped the notice of U.K. prosecutors and legislators that U.S. prosecutors use DPAs to resolve an increasingly broad array of allegations. Given the historic challenges U.K. prosecutors have faced in prosecuting organizations in the English courts, if DPAs are seen to facilitate enforcement action against organizations, then support will likely build for DPAs to be made more generally available as an enforcement tool. The U.K. Government also maintained its position that only organizations would be eligible for DPAs–not individuals. By contrast, U.S. prosecutors may enter DPAs with individuals, and in fact reached several high-profile individual agreements in 2012. The historic roots of DPAs and NPAs in the United States were in the prosecution of individuals (e.g., petty crime by youthful offenders).

Before DPAs become regular fare in the United Kingdom, one important preliminary step must occur: the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Director of the Serious Fraud Office must issue a DPA Code of Practice for Prosecutors. The U.K. Government intends that this Code of Practice will ensure that DPAs respect the “key principles of transparency and consistency.” This public document will instruct when a prosecutor could “consider entering into a DPA,” the “principles” guiding that decision, and “any factors which might suggest a DPA was unsuitable.”

In the wake of the plea agreement that U.K. authorities entered with Innospec Ltd. in 2010, the presiding judge, Lord Justice Thomas, nearly rejected the settlement for lack of judicial input on its terms. With this in mind, the pending DPA law envisions an early and active role for the U.K. judiciary in the negotiation and approval of all DPAs. This represents a contrast to the role of the judiciary in the United States, which generally plays a limited role in approving agreements once they have been drafted.

Under the proposed U.K. regime, after a prosecutor and a company agree in principle to a DPA, the prosecutor must initiate proceedings in Crown Court (which would take place in private) and receive preliminary approval to continue negotiations. Ninety-two percent of respondents to the DPA consultation agreed that a private preliminary hearing would best “limit risks to organizations” and ensure that any future prosecution is not jeopardized. After the parties finalize the text of a DPA, the pending bill requires the judge to approve it in open court. The judge must again find that (1) the DPA is “in the interests of justice,” and (2) the “terms are fair, reasonable and proportionate.” Notably, any financial penalty a U.K. DPA imposes must be “broadly comparable to the fine that a court would have imposed” on the organization if convicted of the alleged offenses. Because a guilty plea in the United Kingdom permits a maximum one-third reduction in the financial penalty, a DPA may likewise only contain a maximum one-third reduction in the financial penalty.

Under the proposed legislation, breaches of a DPA may be handled in two ways. In the event of a minor breach, prosecutors may apply the consequence provided for in the DPA without referral to the court but must publish their reasons for doing so. Otherwise, the prosecution may refer the breach to the court. If the court finds “on the balance of probabilities” that a breach has occurred, the court may either terminate the DPA or invite the parties to submit “proposals to remedy” the breach. If the court terminates the DPA, the prosecution, at its discretion, may then apply to have the suspension of the indictment lifted. In the United States, DPAs and NPAs nearly universally allow DOJ the exclusive ability, without any judicial input, to determine whether a breach has occurred and what remedies may be needed to cure the breach.

The U.K. Government intends to pass the Crime and Courts Bill containing the DPA legislation by spring 2013. Under present proposals, DPAs would only be available in England and Wales. The U.K. Government will encourage the both the Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly to adopt DPA procedures, but neither body is considering DPA legislation at this time.

Conclusion

As we close the books on 2012, it was another noteworthy year for corporate DPAs and NPAs with record penalties touching $9.0 billion and nearly a record number of DOJ agreements. Mr. Breuer’s assessment that DPAs and NPAs have “become a mainstay of white collar criminal law enforcement” appears accurate. Gibson Dunn has negotiated numerous agreements over the last nearly 20 years. Throughout this time, the trend has remained consistent: companies and DOJ turn to DPAs and NPAs with increasing frequency to resolve high-profile, complex criminal settlements. Despite some persistent but unfair criticisms, the reasons for the continuing upward trend are compelling. They enable prosecutors, as DOJ officials have themselves explained, to tailor punishment and remediation measures more accurately to satisfy the principles of prosecution while mitigating the risks of litigation and collateral effects on innocent parties. Companies, for their part, see the benefits of finality in negotiated settlements without the potential collateral consequences of indictment that Mr. Breuer summarized. In 2013 and beyond, we only expect the trend to continue.

The full publication is available here.

Print

Print