Dan Ryan is Leader of the Financial Services Advisory Practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Mr. Ryan, Jeff Lavine, Adam Gilbert, and Armen Meyer. The complete publication, including appendix, is available here.

The board’s role in risk governance continues to attract the attention of regulators who demand that the appropriate risk tone be set at the top of financial institutions. While the largest US banks have made significant progress toward meeting these expectations, many institutions still have a lot of work to do.

Our observations of the policies and practices of the largest US banks indicate that boards have undergone structural and functional transformation in recent years. We are finding that this transformation has been fueled not only by banks’ need to satisfy regulators, but also by their own realization of the benefits of stronger risk governance. We believe the post-crisis regulatory requirements and heightened expectations for risk governance, when fully implemented, will lead to improvements in the board’s understanding of risk taking activities and position the board to more effectively challenge management’s actions when necessary.

Structurally, the largest banks now have board risk committees that are increasingly composed of independent directors and directors with relevant expertise (e.g., former regulators or financial services executives). Additionally, an expanded set of functions are delegated by the full board to these committees, including formally approving the bank’s risk management framework and overall risk appetite.

Despite these noteworthy improvements, banks still have more work to do to keep up with regulatory expectations, particularly with respect to board approval of the Chief Risk Officer’s (“CRO”) appointment and compensation, and creating direct CRO reporting lines to the board. Furthermore, as regulatory expectations around risk governance continue to rise, banks should improve their policies and practices in parallel.

This post analyzes banks’ current board risk governance practices and regulatory expectations, identifies areas for improvement, and provides our view of what banks should be doing now to address them.

Bank risk governance practices

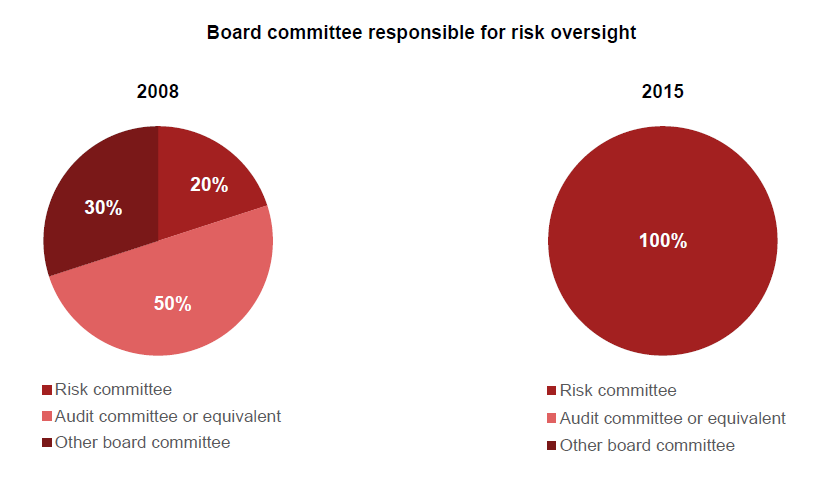

Prior to the 2008 crisis, many banks did not have a board risk committee. Instead, risk oversight was delegated to audit committees or divided among other functional committees. Even where a dedicated risk committee existed, its focus was often limited to specific legal entities and risks within the firm, as opposed to the whole enterprise.

The ineffectiveness of this approach prompted regulatory action in the form of heightened standards issued by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) [1] and risk oversight guidance issued by the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (“BCBS”). In addition, US regulators have introduced board risk oversight requirements into a wider array of other regulatory requirements, including the Federal Reserve’s (“Fed”) Enhanced Prudential Standards (“EPS”), [2] and Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review. [3]

In response to these expectations, boards have undergone significant transformation. Our detailed analysis of the ten largest banks (“Banks”) [4] suggests that changes in this area can be divided into two categories: developments in board structure and composition, and changes in board responsibilities.

Developments in board structure and composition

Increased prevalence of board risk committees and director independence

In recent years, the primary responsibility for risk oversight has shifted from audit or other committees to risk committees of boards. As illustrated below, 100% of the ten largest Bank boards now have a dedicated risk committee, compared to only 20% in 2008.

While all Banks are now required to have dedicated risk committees, [5] boards’ structural changes have not been driven solely by regulatory requirements. Rather, Banks have realized the need to improve their risk oversight regardless of such requirements, as evidenced by changes in risk committee composition since 2008 that go beyond regulatory requirements. These changes have resulted in larger risk committees that include more independent directors than before.

With respect to committee size, our analysis of Banks’ 2015 risk committee charters shows that nine of the ten now require a specified minimum number of directors to sit on the risk committee, even though no minimum number is prescribed under existing regulations. Furthermore, while most Banks’ charters prescribe a minimum committee size of three directors, institutions have exceeded even their self-imposed requirements, placing a median of six to seven directors onto risk committees. These changes reflect not only the importance of the committees’ role but also a desire to increase director participation and understanding of risk issues.

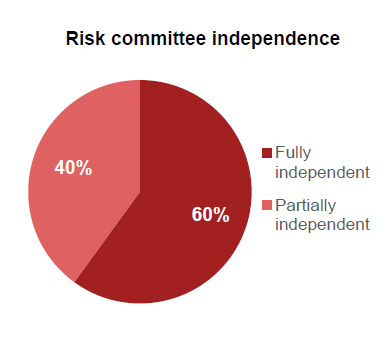

Risk oversight committees have also become more independent, partly in response to regulatory requirements. Under the Fed’s EPS, Banks must have at least one independent member [6] on their risk committee, while the OCC guidelines require at least two independent members on the board itself. Banks have gone well beyond regulatory requirements in this area, with 60% of institutions currently having a fully independent risk committee. [7]

Furthermore, most Banks with partially independent risk committees currently have only one non-independent director on the committee, often the firm’s CEO. These changes indicate that Banks realize the significance of director independence as a tenet of strong corporate governance to facilitate the board’s objective assessment of senior management.

More directors with risk experience

Under the EPS, the risk committee must include at least one director with experience in managing risk exposures of large, complex firms. While this requirement has not yet been formalized as part of the board charter at every Bank, in practice many Banks have at least one person on the risk committees with relevant experience, often a former risk executive of a peer institution.

In addition to directors with industry experience, a growing number of Banks are placing former regulators on their boards and their risk committees. Besides having a view of effective risk governance practices across the industry, these directors can provide clearer insight into regulatory expectations.

Developments in risk committee responsibilities

The structural transformation of board risk committees at the largest institutions has been accompanied by the committees playing a more active risk governance role. Although Banks have made significant progress toward meeting regulatory expectations in this area, necessary changes have not yet been implemented at several institutions.

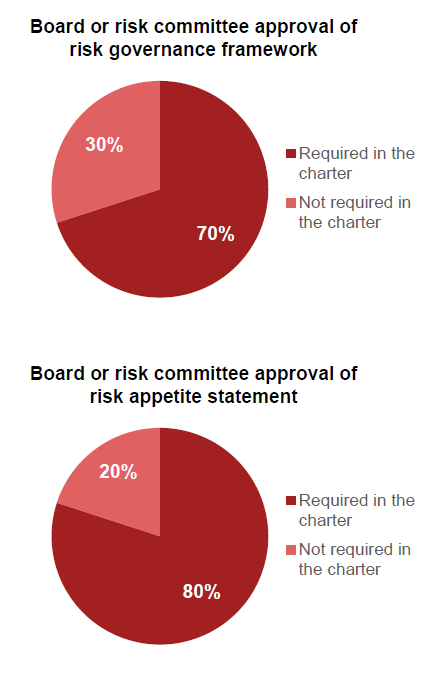

For example, 30% of Banks have not formalized in their board charters a requirement for the risk committee to approve the Bank’s risk governance framework, as required under EPS. A similar 30% are yet to require their board (or the risk committee) to perform an annual self-assessment, [8] as expected by the OCC. Finally, about 20% of Banks have not yet formalized the requirement that their board (or the risk committee) annually approve the institution’s risk appetite statement (a key component of the risk governance framework), as required by the OCC. [9]

Areas for further improvement

In addition to formalizing practices that meet regulatory expectations but have not yet been incorporated into Bank board charters, institutions should also address gaps that exist between current practices and regulatory requirements in several other areas.

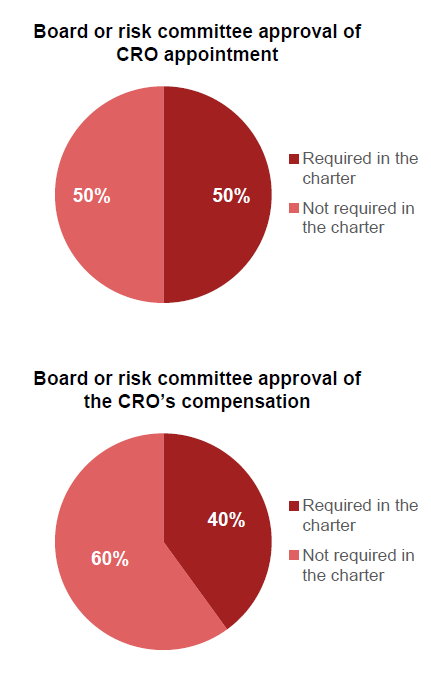

Our analysis points to CRO appointment and compensation as the most significant of such shortfalls. As the primary executive responsible for risk management, CROs play a critical role in the institution’s day-to-day risk management activities. Accordingly, the OCC requires that the board or risk committee approve the CRO’s appointment and compensation to ensure that the CRO has the necessary expertise, and that CRO compensation incentivizes effective risk management (and not only business performance). Despite this requirement, board or risk committee approvals of CRO appointment and compensation are currently carried out (and formalized in charters) by only 50% and 40% of Banks, respectively.

CRO reporting to the board is another area where Banks’ policies and practices have yet to fully meet regulatory expectations. Regulators believe that a direct reporting line between the CRO and the board facilitates the board’s independent judgement and management challenge, and better informs the board of the firm’s risk profile and emerging issues. Accordingly, both the Fed and OCC require increased interactions between the CRO and risk committee through direct reporting lines. However, only 50% of Banks’ charters currently establish a direct reporting line between the CRO and the risk committee (although more Banks utilize direct reporting lines in practice, based on our observations). [10] Furthermore, only 70% of Banks’ charters require regular (either direct or indirect) reporting by the CRO to the committee. [11]

Beyond these specific areas, our observations also indicate that industry practices are evolving to meet broader, more qualitative regulatory expectations around the board’s risk governance role. Namely, regulators expect the board to hold management accountable (through effective review and challenge) for (a) executing the risk governance framework, (b) keeping the board apprised of risks facing the organization, and (c) adhering to the board-defined risk appetite.

To do so, the risk committee should be fully informed of the institution’s risks and exposures, and steps taken to mitigate risks under the risk management framework. The table below lists specific regulatory expectations in this area and corresponding industry best practices based on our observations.

Effective risk review by the board

| Regulatory expectations | Industry best practices |

|---|---|

| The risk committee should receive sufficient information from senior management to understand the bank’s material risks and exposures. This information should be received at least quarterly, or when there are material developments. | Reports to the risk committee provide timely, concise, and accurate information, with key takeaways concerning:

|

| Reports to the risk committee should include a discussion of key limitations, assumptions, and uncertainties within the risk framework, so that the board is fully informed of any weaknesses in the process and can effectively challenge reported results. | Reports to the risk committee include the CRO’s assessment of end-to-end risk management and reporting. This assessment outlines the strengths and limitations of the information provided to the risk committee, including those related to data, models, and report production processes. |

| Reports to the risk committee should include senior management’s strategies to address identified key limitations in the risk management framework, so that the board can assess reported strategies and take appropriate action to address identified weaknesses as needed. | Reports to the risk committee include high-level summaries of efforts to improve risk data quality and accuracy, and assessments of effectiveness of controls in place to produce and aggregate risk information. |

What banks should be doing

Given that regulatory standards for the board continue to rise, they should be considered a starting point from which banks, especially those with over $50 billion in assets, should further improve. Furthermore, regulators will likely continue their horizontal supervision of firms (i.e., evaluating progress at each firm relative to those of its peers), so banks should also assess themselves against peer institutions. As a result, banks should, at a minimum:

- Explicitly capture regulatory expectations in board risk committee charters to demonstrate a commitment to meeting regulatory expectations, especially around the CRO’s expertise and performance

- Seek additional independent board members with risk management expertise

- Focus periodic board training sessions on risks or activities that have a significant impact on the institution, and on new or changed regulatory requirements

- Establish adequate processes for risk issue escalation, ownership, and resolution

- Increase the risk committee’s direct interaction and communication with the CRO, including regular risk reporting and follow up communication

The complete publication, including appendix, is available here.

Endnotes:

[1] See PwC’s Regulatory brief, Risk governance: Banks back to school (September 2014), discussed on the Forum here.

(go back)

[2] See PwC’s First take: Enhanced prudential standards (February 2014), discussed on the Forum here.

(go back)

[3] See PwC’s First take: CCAR stress testing (March 2015), discussed on the Forum here.

(go back)

[4] We analyze Bank of America, BNY Mellon, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, PNC Financial, State Street, US Bancorp, and Wells Fargo, using publically available information supplemented by our own industry observations.

(go back)

[5] Under the Federal Reserve’s Enhanced Prudential Standards, both domestic bank holding companies (BHCs) and foreign banking organizations (FBOs) that have over $10 billion in assets and are publically traded are required to establish board risk committees. The asset threshold is increased to $50 billion for non-publically traded BHCs and FBOs. Although, the OCC does not explicitly require a dedicated board risk committee, its guidelines indicate that banks’ board of directors should actively oversee risk-taking activities and hold management accountable. The OCC’s guidelines apply to (a) insured national banks, federal savings associations, and federal branches of foreign banks (collectively “banks”) with average total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more, (b) banks below $50 billion if the Bank’s parent controls at least one other entity to which the Guidelines apply, and (c) banks below $50 billion that have highly complex operations or otherwise present heightened risk, as determined by the OCC.

(go back)

[6] An independent director is generally one who is not an officer or employee of the company, or a member of an officer’s or employee’s immediate family.

(go back)

[7] Committee charters also often contain provisions for the CRO to attend board risk committee meetings. However such provisions do not grant a CRO (who is not otherwise a member of the board) committee membership and/or voting rights, thus preserving the complete independence of the risk committee.

(go back)

[8] This self-assessment is in addition to, and distinct from, annual independent assessments of the risk governance framework and end-to-end management processes, which are often conducted by internal audit or another independent third party.

(go back)

[9] As a subset of the risk governance framework, the risk appetite statement helps an institution understand and manage its risks by translating risk metrics and methods into strategic decisions, reporting, and day-to-day business decisions.

(go back)

[10] We have also observed a similar trend in Chief Compliance Officer (“CCO”) reporting to the CEO, which suggests that the benefits of direct reporting lines go beyond the CRO. Whereas traditionally CCOs have reported to the CEO indirectly via the General Counsel, a trend is emerging toward direct CCO reporting to the CEO.

(go back)

[11] In addition, Banks’ board charters generally include the ability of the CRO to meet with the risk committee on an ad hoc basis should immediate escalation of risk issues be necessary, even where the CRO does not provide regulator reports directly to the board.

(go back)

Print

Print