Beth Young is a lecturer at Harvard Law School and a senior research fellow at The Corporate Library. This post is based on a paper prepared for the Council of Institutional Investors and the Shareowner Education Network; the paper is available here. The views and opinions expressed in the paper are those of Ms. Young and do not necessarily represent views or opinions of Council members, board of directors, or staff.

In June 2009, the Securities and Exchange Commission proposed to require public companies, under certain circumstances, to include in the company proxy statement and proxy card the names of director nominees submitted by substantial long-term shareholders (generally referred to as “access to the proxy” or “proxy access”). At the same time, the SEC proposed to amend Rule 14a-8(i)(8), the shareholder proposal rule’s “Election Exclusion”, to reverse a 2007 amendment and allow shareholders to submit proposals seeking the adoption of a proxy access regime. The comment period for the rulemaking expired on August 17, 2009, and the SEC received hundreds of comment letters.

Among commenters opposed to the adoption of Rule 14a-11, a common theme was that the SEC should refrain from imposing a uniform federal access procedure. Instead, these commenters urged, the SEC should facilitate private ordering to permit shareholders at each individual company to decide whether proxy access is desirable and to establish its precise contours. To that end, these commenters generally supported the SEC’s proposal to amend the Election Exclusion.

Two distinct types of private ordering were promoted in comment letters:

- Opting in: The default rule would be no proxy access. A company could opt in to a proxy access regime through (a) a bylaw adopted by the board, either in response to a non-binding shareholder proposal seeking access or on its own initiative; or (b) a bylaw adopted by shareholders. A proposal promoting proxy access, including a shareholder-initiated bylaw amendment, could be included in the company proxy statement—provided the SEC adopts the proposed amendment to the Election Exclusion—or it could be the subject of an independent solicitation. Advocates of an opt-in approach pointed out that Delaware recently enacted changes to its corporate law clarifying that bylaws establishing a proxy access regime are permissible under Delaware law.

- Opting out: The default rule would be proxy access established by SEC rule. A company could opt out of the access procedure if (a) its shareholders approved a management proposal to opt out or (b) its shareholders adopted a bylaw providing that the proxy access procedure would not apply.

In some discussions, the opt-out approach has been framed as including both opt-out and opt-in elements. In this conception, a company would be permitted to opt out of the access procedure established in Rule 14a-11; either at that time or a later time, the company could opt into a proxy access procedure of some kind, at the behest of shareholders using the shareholder proposal process or on the board’s own initiative.

Thus far, the proxy access debate has centered on the legitimacy of federal regulation on this subject, with supporters urging that the proposed access procedure is a logical extension of the SEC’s power over the proxy solicitation process and opponents arguing that the proposed rule represents too much of an incursion on states’ traditional jurisdiction over corporations’ internal affairs. Some attention has been paid to whether the virtues of an enabling approach—allowing companies to adopt a different rule from the default and thus to tailor practices to company circumstances—justify a departure from the mandatory approach seen in all other areas of U.S. securities regulation.

Missing from the discussion, however, is a systematic analysis of the feasibility of private ordering at U.S. public companies. A primary selling point of private ordering in the proxy access context is that it would ensure that the arrangement at a given company reflects the preferences of its shareholders, preferences that are informed by those shareholders’ views on whether proxy access would be value enhancing (and if it would be, the ideal terms of the procedure). Implicit in many of the comments supportive of private ordering are assumptions that shareholders can easily propose appropriate proxy access procedures at individual companies and that the shareholder voting process is free from significant distortions.

To test those assumptions, this study analyzes the prevalence of two governance arrangements—limitations on shareholders’ ability to amend the bylaws and capital structures involving multiple classes of stock with disparate voting rights—in three different market indices: the S&P 500, the Russell 1000 and the Russell 3000. [1] If shareholders cannot amend the bylaws, both opting into and out of proxy access through a shareholder-adopted bylaw amendment are impossible. Supermajority voting requirements to amend the bylaws create similar, though less severe, challenges. Multiple class stock structures with unequal voting rights can prevent voting outcomes from reflecting the views of holders of a majority of a company’s shares. Each of these arrangements is discussed in more detail below.

Overall Findings

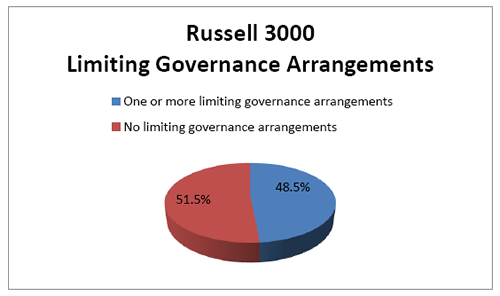

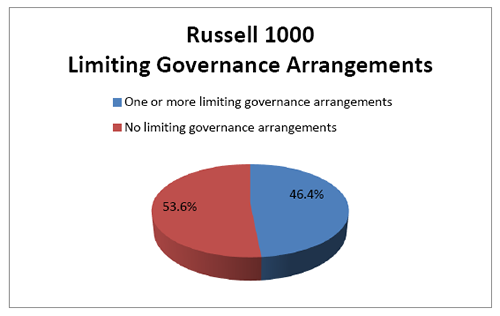

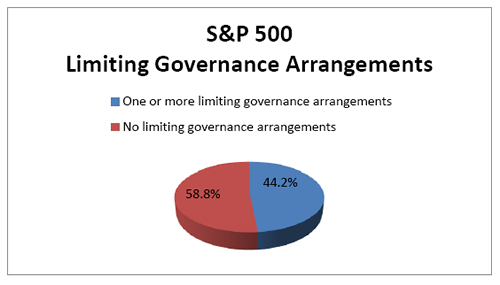

Just under half the companies analyzed had either a restriction on shareholders’ ability to amend the bylaws or multiple classes of stock with disparate voting rights, or both. Among Russell 3000 companies, 48.5% of companies have at least one of these two governance arrangements in place.

Of Russell 1000 companies, 46.4% limit shareholders’ power to amend the bylaws or use a capital structure with disparate voting rights for multiple classes stock, or both.

Finally, 44.2% of S&P 500 companies restrict shareholders’ ability to amend the bylaws or have multiple classes of stock with disparate voting rights, or both.

Initiating Governance Change

Both the opt-in and opt-out regimes suggested by various commenters contemplate shareholders initiating changes to companies’ governance arrangements using the shareholder proposal process. A board can adopt an access procedure without prompting from company shareholders, but the current paucity of such arrangements suggests that shareholders will need to initiate the process at many companies.

Shareholder proposals may be made in binding or precatory form. A precatory proposal asks the company to take the desired action and leaves implementation to the board of directors. In other words, even if passed by shareholders, it does not bind the board. A binding proposal takes the form of an amendment to the company’s bylaws; it takes effect without further board action upon approval by the requisite percentage of shares.

For opt-in proposals, it is likely that shareholders will wish to submit binding proposals in some cases in order to retain control over key terms of proxy access, such as the amount of stock a shareholder must own in order to use the access procedure, the length of the holding period, the maximum number of candidates who can be nominated and the method of resolving conflicts between competing nominating shareholders or groups. A binding proposal may be viewed as preferable at a company whose board has already adopted an access procedure bylaw with terms seen as too onerous, or at a company where shareholders are skeptical that the board would implement a precatory proposal in a manner acceptable to shareholders.

In the case of opt-out proposals, it is less clear how shareholders would initiate the change because there is no precedent for a shareholder opt-out from a federal securities regulation. Under the law of some states, companies can opt out of the operation of certain anti-takeover statutes in a number of ways, including a statement to that effect in a bylaw. It is possible, then, that an opt-out procedure might involve shareholders adopting a bylaw opting out in whole or in part from a uniform federal access procedure. (Another possibility, not involving shareholder initiation, is that shareholders might ratify a board-adopted bylaw amendment.)

State Law and Proxy Access Proposals

Under the shareholder proposal rule, a company may exclude a proposal from its proxy statement if, among other things, (a) it is not a proper subject for shareholder action under the law of the state in which the company is incorporated or (b) implementing the proposal would cause the company to violate state law. Although a precatory proposal will not generally be subject to exclusion on this ground, a shareholder cannot submit a binding bylaw amendment on proxy access if the amendment would be invalid under the law of the state where the company is incorporated.

Supporters of private ordering point to recent statutory changes in Delaware-where the Delaware General Corporation Law now makes it clear that a bylaw establishing a proxy access regime is permissible–as evidence that there are few barriers to company-by-company reform on the issue. [2] Although “[a]ctive consideration” [3] is being given to amending the Model Business Corporation Act to follow Delaware’s lead, any changes to the MBCA must be adopted by individual state legislatures.

Among Russell 3000 companies, 1,713, or 57.1%, are incorporated in Delaware. Among larger capitalization companies, the proportion is slightly higher; 57.8% of Russell 1000 companies and 60.8% of S&P 500 companies are incorporated in Delaware. Thus, at 40% or more of companies analyzed for this study, there is no assurance that a shareholder-initiated bylaw amendment on proxy access would be valid. [4]

Limitations on Shareholders’ Ability to Amend the Bylaws

In addition to state law, companies’ own governance arrangements affect the ability of shareholders to initiate governance reforms using the bylaw amendment process. Shareholders cannot submit a binding proposal establishing or opting out of a proxy access procedure at companies where shareholders do not have the power to amend the bylaws. Although Delaware law does not permit the elimination of this right, the corporate law of some states either (a) supplies a default rule of no shareholder ability to amend the bylaws (thus requiring companies to provide a different rule in their charter or bylaws) or (b) supplies a default rule empowering shareholders to amend the bylaws but allows companies to eliminate the right entirely.

Approximately 4% of companies in the Russell 3000 and Russell 1000 indices do not allow shareholders to amend the bylaws. Among S&P 500 companies, about 3% prohibit shareholder bylaw amendments altogether.

Larger proportions of companies have supermajority voting requirements (a proportion larger than a simple majority or 50% plus one share) for shareholders to amend bylaws. A supermajority vote threshold is not the same as a prohibition, to be sure. But the way a supermajority vote threshold is calculated makes it a significant barrier to shareholder action. With many items on which shareholders vote—the election of directors, for example, or the approval of an equity compensation plan—the denominator is votes cast. For a bylaw amendment, by contrast, the denominator is shares outstanding, so an 80% requirement to amend the bylaws requires the sponsor of the bylaw amendment to ensure both that its case is persuasive to a very large proportion of shares voting (in other words, that they vote “for” instead of “against”) and also that turnout is sufficiently high for support among shares voting to translate into approval.

Data relating to board declassification suggest that supermajority vote requirements make passage of a ballot item significantly less likely, though circumstances vary from company to company. An analysis of shareholder voting on management proposals to declassify the board from 2004 through 2009, submitted at companies where shareholders had previously approved one or more shareholder proposals urging declassification, illustrates this phenomenon. (Most companies classify their boards in the charter, so companies seeking to declassify the board must seek shareholder approval for a charter amendment.)

The data show a lower approval rate for management declassification proposals requiring a supermajority vote than for those requiring only a simple majority vote, with both thresholds calculated out of outstanding shares. All of the proposals requiring a simple majority were approved, compared with 85% of those needing a supermajority vote. This difference is even more meaningful considering that these declassification proposals would have carried a “for” vote recommendation from the board and that brokers could vote uninstructed shares in favor of these proposals under New York Stock Exchange Rule 452. (Broker votes are typically cast in accordance with management’s recommendation; for a fuller discussion of broker voting, see “Distortions in the Shareholder Voting Process”.)

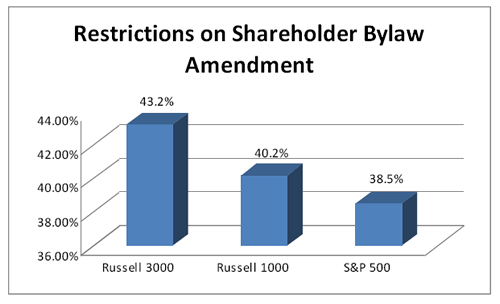

A supermajority vote requirement to amend bylaws is present at 39.1% of companies in the Russell 3000 index. This figure is a bit lower among Russell 1000 companies, 36.1% of which use a supermajority threshold, and S&P 500 companies, where 35.4% employ a supermajority vote standard.

Between outright prohibition and supermajority voting requirements, shareholders at approximately 40% of companies in the three indices face meaningful barriers to adopting a bylaw amendment opting into or out of a proxy access regime. A standard other than a simple majority is in place at 43.2% of Russell 3000 companies, 40.2% of Russell 1000 companies and 38.5% of S&P 500 companies.

Distortions in the Shareholder Voting Process

Discussions about shareholder voting generally assume that a proposal’s approval or defeat reflects the preferences of holders of a majority of shares (or supermajority, as the case may be). Comments promoting private ordering exhibit this tendency. For example, Professor Grundfest stated in his comment, “Fully enabling rules would create shareholder referenda pursuant to which shareholders could propose, and a majority could adopt, proxy access standards for each individual corporation.” [5]

While that is the case at companies with one class of voting stock, it does not hold at companies with two or more classes of voting stock and disparate voting rights. This kind of capital structure assigns greater voting power to holders of one class of shares; these holders are often insiders or members of a company’s founding family or group and the supervoting shares are generally not available to the investing public. For example, holders of public Class A shares may have one vote per share while holders of Class B shares have 10 votes per share. Such arrangements distort the relationship between voting power and economic exposure and allow holders of what may be a very small number of shares to determine voting outcomes.

Of Russell 1000 companies, 8.8% have a multiple class capital structure with disparate voting rights. The proportion is a bit smaller among Russell 3000 companies, at 7.5%, and companies in the S&P 500, where 7.1% of companies have this governance arrangement.

There is very little overlap between companies that restrict shareholders’ ability to amend the bylaws and those that have multiple classes of stock with disparate voting rights. A very small fraction of companies—2.3% of Russell 3000, 2.4% of Russell 1000 and 1.4% of S&P 500 companies–has both of these governance arrangements.

In the case of management proposals to opt out of proxy access, the New York Stock Exchange’s broker-may-vote rule, Rule 452, may supply an additional distortion. Rule 452 allows a broker holding shares in “street name” for a customer to cast proxy votes on certain “routine” items if the broker does not receive voting instructions from the customer at least 10 days before the scheduled shareholder meeting. A management proposal is classified as routine, and thus eligible for broker voting, unless it is added to the list of non-routine items in the rule. (A shareholder proposal opposed by management, by contrast, is categorized as non-routine.) Broker votes are typically cast in accordance with management’s recommendation. [6]

Although the impact of broker voting varies from company to company, it can significantly bolster support for management initiatives. A study commissioned by the Council of Institutional Investors found that the elimination of broker voting would have increased the number of directors at companies with a majority vote standard who received “withhold” or “against” votes in 2007 of at least 25% from 68 to 98; similarly, the number of directors at plurality-vote companies receiving such votes would have increased from 384 to 514. [7]

Conclusion

The case for private ordering assumes that shareholders will be able to initiate proposals opting into or out of an access regime, as well as that voting outcomes reflect the will of the majority. Data on bylaw amendment limitations show that at between 38 and 43% of companies, depending on the index, shareholders are either unable to amend the bylaws or face significant challenges in the form of supermajority vote requirements. A lack of clarity regarding the validity of binding proxy access shareholder proposals in states other than Delaware further calls into question the feasibility of shareholder-initiated opt-in efforts at the nearly 40% of companies incorporated outside Delaware.

Moreover, at between seven and nine percent of companies, the capital structure varies from one share/one vote, giving disproportionate influence to holders of supervoting shares. Additional distortions could be introduced into the voting process for management proposals to opt out of proxy access as a result of the operation of the broker-may-vote rule.

Endnotes

[1] Because data were not available for all companies in the indices, the analysis was performed on 491 companies in the S&P 500, 924 companies in the Russell 1000 and 2,817 companies in the Russell 3000. Data were drawn from The Corporate Library’s database of North American governance information, and were current as of October 2009. The S&P 500 is a stock market index whose constituents have market capitalizations in excess of $3 billion and satisfy certain other criteria. The Russell 1000 index is made up of the 1000 largest U.S. public companies by market capitalization; similarly, the Russell 3000 constituents are the 3000 largest U.S. public companies by market capitalization.

(go back)

[2] See section 112, Delaware General Corporation Law.

(go back)

[3] Troy A. Paredes, Commissioner, Securities and Exchange Commission, Remarks at Conference on “Shareholder Rights, the 2009 Proxy Season and the Impact of Shareholder Activism,” at the Center for Capital Markets Competitiveness, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, June 23, 2009 (available at http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2009/spch062309tap.htm).

(go back)

[4] North Dakota has a statutory proxy access right but no statute addressing the validity of a proxy access bylaw. In any event, no companies in the S&P 500 or Russell 1000, and only two companies in the Russell 3000, are incorporated in North Dakota.

(go back)

[5] Joseph A. Grundfest, “Internal Contradictions in the S.E.C.’s Proposed Proxy Access Rules,” working paper dated July 24, 2009, at 3 (submitted as comment letter).

(go back)

[6] See Latham & Watkins LLP webcast, “Kicking Off the 2009-10 Executive Compensation Season: A Real-Time Discussion of Critical Issues and Looming Legislative and Regulatory Changes,” at 1 (available at http://www.lw.com/upload/pubContent/_pdf/pub2841_1.pdf).

(go back)

[7] See Comment Letter of Council of Institutional Investors on “Proposal to Eliminate Broker Discretionary Voting for the Election of Directors” (SR-NYSE-2006-92), at 2 (Mar. 19, 2006) (available at www.cii.org).

(go back)

Print

Print