Simon Wong is Managing Director at Governance for Owners and Adjunct Professor of Law at Northwestern University School of Law. This post is based on an article that recently appeared in the Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law, which is available here.

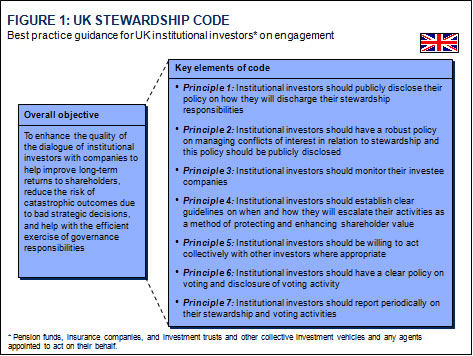

As the dominant owners of listed companies in many developed markets, institutional investors have been under increasing pressure to act as responsible shareholders. In the UK, where institutions own more than 70% of the stock market, a Stewardship Code has been developed to encourage pension funds, insurance companies, and their asset managers to monitor and engage investee companies actively with the view to protect and enhance shareholder value (see Figure 1). Similar efforts are underway in Canada, France, the Netherlands, and other markets.

However, attempts in recent decades to convince institutional investors to act as active, long-term oriented “stewards” have fallen short. A recent examination by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development of the contributing causes of the global financial crisis concluded that institutional investors were generally not effective in monitoring investee companies.

Five underlying structural deficiencies

Why is it so difficult for institutional investors to act as stewards? In essence, it is because stewardship is not in their genetic makeup. Modern investment management practices and characteristics make it extremely hard for an active, long-term ownership mindset to take hold. These include:

- Inappropriate performance metrics and financial arrangements that promote trading and short-term returns

- Excessive portfolio diversification that makes monitoring difficult

- Lengthening share ownership chain that weakens an “owner” mindset

- Misguided interpretation of fiduciary duty that accords excessive deference to quantifiable data at the expense of qualitative factors

- Flawed business model and governance approach of passive funds

Inappropriate performance metrics and financial arrangements

Many asset managers are evaluated and compensated based on short-term, relative performance. Unsurprisingly, investment managers focus on delivering short-term returns, including by pressuring investee companies to maximise near-term profits.

One UK local authority pension scheme, for instance, reviews the performance of fund managers quarterly and focuses on the deviation of portfolio returns from established benchmarks and anticipated range of returns for future quarters. While evaluating the performance of investment managers on a relative basis – that is, the extent to which they outperform or underperform a market index such as the FTSE 100, S&P 500, or MSCI World Index – can help ensure that they are not rewarded undeservingly in a bull market or punished inequitably in a market downturn, it can also encourage herd behaviour and a short-term focus, particularly if a narrow time interval is utilised to measure performance.

According to the Marathon Club, an organisation that promotes long-term investing, “The quarterly monitoring process, with a focus on performance relative to an index, has become the norm in the investment industry and has been blamed for promoting short-term behaviour by investment managers.” A veteran UK money manager complains that “fund managers – even seasoned ones – are under intense pressure from colleagues and clients if they experience a string of two to three quarters of underperformance.”

In terms of compensation, a 2009 survey by investment consultant Mercer revealed that bonuses for individual fund managers are, to varying degrees, “linked to performance versus a benchmark or manager rankings table in any given year.” Some asset manager respondents stated that “incentive systems are often devised to pay fund managers to be aggressive over shorter time periods, especially pronounced for mutual funds, where managers are often incentivised against quarterly performance versus a market benchmark or quartile rankings.”

Furthermore, the widely-used ad valorem approach – where fees are calculated based on assets under management rather than outperformance – has been criticised for encouraging investment managers to grow by attracting inflows of new money rather than by expanding existing assets through superior investment performance.

Excessive portfolio diversification

The techniques employed by many institutional investors to manage risk – such as pension funds appointing multiple investment managers and fund managers constructing portfolios around the market benchmarks against which their performance is measured – often result in excessive diversification, with equity portfolios containing hundreds or even thousands of stocks.

One UK pension fund, for example, holds shares in most of the 700-plus companies in the UK All Share Index. Meanwhile, a big US pension fund has more than 5,000 equity holdings in the US alone and a sovereign wealth fund holds shares in 8,000-plus companies globally.

Similarly, passive and active asset managers that replicate market indices can end up with hundreds of companies in their portfolios. It has also been suggested that the ad valorem fee structure discussed above encourages large portfolio holdings as diversified funds are more able than concentrated ones to absorb significant inflows of new money.

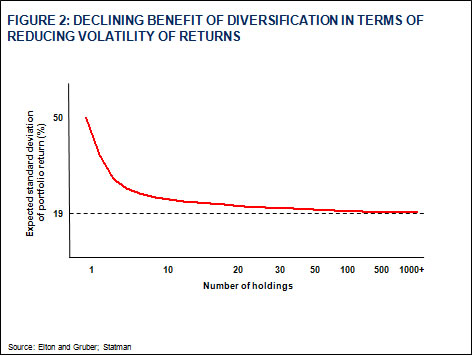

Large portfolios, however, give rise to difficulties in monitoring – particularly the resource-intensive engagements between institutional investors and boards of directors contemplated by stewardship codes in the UK and other markets – and weaken an “ownership” mindset. Former UK City Minister Lord Myners complained recently that investment management today is characterised by “portfolios with high diversification and low exhibited stock conviction.” Moreover, studies have shown that the principal benefit of diversification – reducing portfolio volatility – diminishes rapidly after 20-50 stocks (see Figure 2).

Lengthening share ownership chain

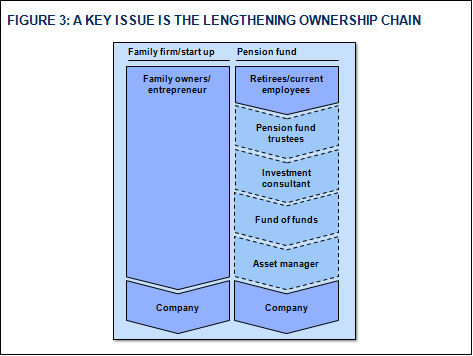

Increasing use of intermediaries – investment consultants, “funds of funds,” external asset managers, and others – in investment management has lengthened the ownership chain of companies and, in the process, lessened the sense of accountability between ultimate investor and investee company.

Compared to a family or founder-run firm, where direct ties often exist between ultimate owners and company management, the distance from pension beneficiaries to investee company is often bridged by several layers of intermediaries (see Figure 3). This phenomenon – termed “separation of ownership from ownership” – has introduced serious agency problems. Delaware Chancery Court judge Leo Strine has commented that institutionalisation of ownership “presents its own risks to both individual investors and more generally to the best interests of our nation” because fund managers may be as likely “to exploit their agency [as] the managers of corporations that make products and deliver services.”

These agency issues have necessitated the introduction of a cascading set of performance measures to monitor intermediaries along the ownership chain. However, because short-term performance metrics are typically employed at each link in the chain, additional problems – such as misaligned time horizons and a trader mentality – have arisen.

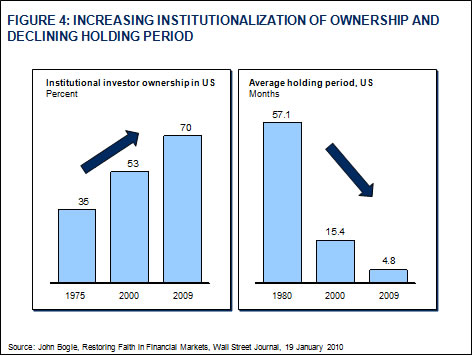

Consequently, it is perhaps no coincidence that rising institutional ownership in the US – from 35% in 1975 to 70% today – has been accompanied by greater portfolio turnover (see Figure 4). Whereas the average stock holding period in the US was nearly 5 years in 1980, it is less than 5 months today. Judge Strine observed that “institutional investors who hold stocks, on average, for a very brief period of time and are highly focused on short-term movements in stock prices have become far more influential and prevalent.”

Misguided interpretation of fiduciary duty

Across the investment chain, there is an increasing emphasis on furthering the economic – as opposed to non-financial – interests of clients and ultimate beneficiaries. A US state pension fund, for instance, declares that the “investment board, staff and investment managers must perform their duties for the exclusive benefit and in the best economic interest of the system’s members and beneficiaries.” Likewise, a UK pension scheme states that the fund’s “overriding obligation is to act in the best financial interests of its members.”

Many asset managers echo the same theme. A large US investment manager, for instance, stresses that its duty is “to manage clients’ assets in the best economic interests of the clients.”

Government has also reinforced this view. In 2008, the US Department of Labor warned that “in the course of discharging their duties, fiduciaries may never subordinate the economic interests of the plan to unrelated objectives.”

Unfortunately, the emphasis on economic interest has contributed to asset owners and asset managers believing that fulfilling fiduciary obligations requires them to evaluate investment and other decisions principally in quantifiable financial terms. A US corporate governance expert remarked that the Labor Department’s guidance implies that “fiduciaries can only justify shareholder activism to increase immediate returns at the company involved.” Such interpretation, however, can result in flawed and harmful decisions.

When evaluating whether it is in the best interest of shareholders to recall a stock on loan in order to vote it, fund managers are required to weigh the value of voting against stock lending revenue to be foregone. Given the difficulty of valuing a vote quantitatively, some fund managers routinely assign it a zero value and, hence, conclude that shareholder interest is better served by not recalling the stock in question, even when contentious items are to be voted upon.

In takeover situations, the decision of asset managers to sell their holdings or accept a bid is guided principally by stock price – which is highly influenced by short-term considerations – rather than a thorough assessment of a company’s long-term prospects. According to a senior executive at an established UK investment house, “In a takeover context, we would typically sell if the stock price rises above our target price, as this is our fiduciary duty to our clients.”

To minimise expenditures, some pension funds seek to pay no management fees – usually expressed as a percentage of assets under management – for passive funds but allow investment managers to earn a financial return via share lending revenues. From an alignment of interest perspective, this is highly problematic because it removes the incentive for the asset manager to maximise portfolio value while introducing severe conflicts of interest. With no management fees to depend on, the investment manager may be reluctant to recall lent shares to vote them because it would then be deprived of its primary source of revenue.

Flawed business model and governance approach of passive funds

Due to comparatively high fees and underperformance of actively managed funds, passive funds – which tend to fully replicate a broad market index such as the S&P 500 or All-Share Index and where exiting individual holdings is not an option – have enjoyed a resurgence of interest among institutional and retail investors in many markets.

In 2009, passive funds experienced inflows in excess of US$100 billion while active funds suffered outflows totalling more than US$300 billion. Witness also the explosive growth of largely passive exchange traded funds (ETFs), which had nominal amounts under management a decade ago but more than US$1 trillion today.

Because passive investing precludes trading in and out of individual stocks and seeks long-term gains in the broad equity market, passive funds and stewardship should be natural bedfellows.

Yet, the bulk of passive funds pay scant attention to corporate governance. Index fund marketing, for instance, focuses almost exclusively on their low cost and tracking error performance (i.e., deviation from benchmark index return). Correspondingly, many passive asset managers allocate meagre resources to proxy voting and engagement with investee companies. A recent study of UK investment firms revealed that passive managers allocated the least resources to stewardship activities, as measured by the ratio of number of stocks held to size of dedicated staff.

It is particularly worrying that some ETFs have taken steps that appear to harm stewardship. One ETF provider, for instance, has decided not to charge any management fees and will instead rely on securities lending to generate income.

Although passive investing underpins the equity portfolios of a substantial proportion of pension funds – in some cases, amounting to 70-80% of their equity exposure – many of them do not scrutinise the stewardship activities of passive managers. When reviewing passive manager performance, pension scheme trustees tend to focus exclusively on tracking error performance rather than the manager’s voting and engagement activities. At a UK public pension scheme, passive asset managers are evaluated strictly on whether tracking errors are within 2% of the relevant index.

Potential way forward

While the structural deficiencies discussed above are indeed worrying, there are a number of potential remedies that could help to provide a more conducive setting for stewardship.

Eliminate unnecessary intermediation and strengthen internal capabilities

First, asset owners should strive to eliminate unnecessary links in the ownership chain and boost in-house expertise. Yale endowment investment head David Swenson, for instance, avoids investment consultants and funds of funds. He is most critical of the latter, arguing that “no one should invest with a fund of funds. If you’re a fiduciary, you should know where the money is going. If you can’t do it yourself, you shouldn’t do it.”

Empirically, investors who invest in hedge funds through a fund of hedge funds have fared worse than those who invest directly. According to Hedge Fund Research, since 1990 funds of hedge funds have generated average annual returns of 8.17% while individual hedge funds have gained 12.15% per annum. Part of the differential is attributed to management and performance fees extracted by funds of hedge funds, which are additional to the fees paid to the underlying hedge funds.

Where possible, pension funds and other long-term asset owners should also strengthen internal capabilities. According to the Marathon Club, “Those funds or sponsors who can sustain and manage an in-house team may find it easier to obtain alignment between the fund’s objectives and the manager’s investment strategy.” In some markets, larger pension funds – such as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), and Universities Superannuation Scheme (UK) – have built substantial in-house investment management expertise.

A recent study of Canadian pension funds found that greater reliance on in-house investment management has brought about stronger performance. In the past decade, the largest 9 Canadian public sector pension funds returned an average 5.5% per annum while their 8 largest US counterparts – which employ outside managers more extensively – gained 3.2% annually. A Canadian pensions expert noted that “research shows internal teams not only save money by cutting high external money management fees, but also perform better as investors because they are more closely aligned to the mission of the pension fund.”

Strong in-house capability, however, does not preclude using outside managers. CPPIB, with assets of C$125 billion, employs external managers in niche areas where it is unable to develop the required expertise.

Where asset owners strive to be active owners, many will need to upgrade their monitoring and engagement capabilities, as the requisite skills for engagement and investment success are substantially different. In a recent survey, 61% of UK pension funds conceded that they lacked the necessary skills to engage effectively with investee companies. Correspondingly, asset owners that delegate engagement activities to fund managers should ensure that the latter possess sufficient competencies in this area.

In countries with many small pension schemes, such as the UK, policymakers should consider facilitating consolidation to build scale and thereby strengthen the ability of pension funds to recruit investment and other talent. In Scotland, a project intended originally to explore the potential for greater resource sharing among 11 small local government pension schemes ultimately concluded that consolidation of schemes was the best way forward. The consulting firm that conducted the analysis noted that “it is increasingly difficult for [smaller] funds to recruit staff with expertise in the ever more complex investment instruments in which their funds invest.” If consummated, this merger will create a sizeable fund with assets of £20 billion. In Wales, some local authorities are similarly exploring a merger among themselves.

Revamp performance metrics and other arrangements

Second, where outside fund managers are retained, asset owners should put in place arrangements – pertaining to such matters as performance evaluation, fee structure, and portfolio turnover – to encourage long-term thinking and active ownership by investment managers.

The starting point is to lengthen the performance review time period and reduce emphasis on relative returns. According to a US value asset manager, “Until managers are evaluated on a longer-term basis, the market will remain short-term focused. Managers should be evaluated on a 5- to 10-year basis, since a market cycle is at least that long.”

The Marathon Club recommends that asset managers be evaluated using a 5-7 year time horizon and that annual reviews focus on a fund manager’s investment process and whether the portfolio assets – in terms of number of holdings, degree of concentration, types of assets, turnover level, valuation ratios, and so forth – match the stated philosophy.

To measure performance quantitatively, it may be sensible to supplement market index comparisons with other metrics, such as internal rates of return for exited investments. Relative comparisons should not be abandoned entirely because active managers should strive to outperform their respective market indices over the long run.

Some asset owners have embraced this approach. Having committed to a three-year investment, a US public pension fund refused to meet the asset manager during the first year to discuss results, believing that a full review of performance should occur only after the second year.

In terms of fee arrangements, asset owners should consider introducing performance fees and spreading fee payments over multiple years. Investment consultant Towers Watson recommends calculating performance fees based on a rolling period of three years or longer.

Additionally, it may be worthwhile to consider tying a meaningful portion of an investment manager’s fees to the quality of its stewardship activities. To accommodate different investment styles, the proportion of fees “at risk” could vary. A higher proportion could apply to corporate governance-oriented activist as well as passively managed funds. For index funds, the reasoning is that “if you can’t sell, you must care.” By contrast, a lower percentage could apply to quantitatively-driven and other short-term oriented asset managers. Asset owners with long-term obligations, however, must decide whether it is consistent with their long-term investment objectives to invest in funds that do not espouse stewardship.

Equally important, fee arrangements that will harm stewardship should be avoided – for example, zero management fee structures where the asset manager earns income exclusively from securities lending.

Moreover, asset owners should consider capping portfolio turnover. Increasing capital market liquidity has lowered transaction costs but also reduced the consequences of imprudent investment decisions and commitment of fund managers to investee companies. As the chief investment officer at a UK investment house remarked, “If investors believe they are always able to enter and exit freely, what is the incentive to engage?” Limiting portfolio churn may prompt asset managers to think longer-term and engage actively with investee companies.

To maintain symmetry, asset owners should be willing to agree to restrictions on withdrawing their funds. Long-term oriented focus funds, for instance, usually impose lock-ups of 2-3 years on investors.

Rationalise portfolio holdings

Third, to improve monitoring capabilities and alleviate free-rider issues, asset owners and asset managers should consider reducing the number of portfolio holdings. Concentration of holdings increases the incentive to monitor investee companies because a greater proportion of gains would accrue to the instigating investor. With fewer holdings in their portfolios, fund managers would be more able to undertake intensive engagements with investee companies, critical in such areas as evaluating board effectiveness where meaningful insights are gleaned through face-to-face meetings rather than scanning annual reports.

To strengthen their capacity to act as active owners, two large Dutch pension funds are contemplating shrinking their equity portfolios from 4,000-5,000 to 300-400 holdings, a potential reduction of more than 90%. In the UK, a large investment house abandoned the practice of replicating, or “hugging,” market indices several years ago and today takes sizeable positions in a small group of core holdings.

A further benefit of fewer portfolio holdings is that it will likely instil a stronger investment discipline. Legendary investor Warren Buffet has noted that “a policy of portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it.”

Firms that construct market indices can help investors to realise this objective by shrinking the number of companies in the largest indices or developing substitute benchmarks that provide broadly equivalent exposure to each market segment but contain fewer companies.

Re-orient the passive investing model

Fourth, asset owners and asset managers should work together to change the business model and governance approach of passive funds so that stewardship is featured more prominently. How passive funds approach stewardship is highly significant given their present size and expected growth. Towers Watson predicts that, over the next 10 years, the proportion of institutional investor assets allocated to passive investing will increase from a 25-33% to 50%.

While it may not be reasonable to expect passive funds to adopt the same resource-intensive intervention approach as focus funds with respect to individual holdings, it would seem sensible for them – at a minimum – to focus on ensuring a sound regulatory framework and undertaking regular, low-intensity engagements with portfolio companies.

To encourage passive investment managers, asset owners may wish to provide explicit incentives – such as fees for good stewardship as suggested above – and revise the metrics used to evaluate their performance. For example, tracking error performance could be supplemented by metrics that capture changes in “beta” over time, such as a multi-year rolling price-earnings ratio or return on equity of the stock market or a market segment.

As investment houses expand their passive product offerings, they should supplement the traditional marketing focus on low cost and tracking error performance with an emphasis on good stewardship.

If passive managers are unable or unwilling to discharge their stewardship responsibilities competently, asset owners should consider undertaking these activities themselves or outsourcing them to specialist providers or industry associations.

Clarify fiduciary duties

Lastly, policymakers should clarify to asset owners and asset managers that discharging fiduciary obligations requires thorough examination of both short- and long-term considerations. It is also important to stress that – when making investment and other important decisions – qualitative assessments could be as vital as quantitative data, especially when precise calculations cannot be made easily, such as regarding the value of a vote.

Furthermore, some commentators have suggested reforming fiduciary standards so that pension fund trustees feel less compelled to conform to mainstream practices regarding their investment and stewardship approaches.

Conclusion

While not all investors need to be stewards and stewardship obligations should be allowed to be discharged in different ways, tackling the underlying structural impediments will make it easier – and more natural – for asset owners and asset managers to adopt an active, long-term oriented mindset.

Print

Print

3 Comments

I agree that diversification may be a losing battle. I remember Warren buffet once saying that if you know what you are doing with a reasonable amount of confidence it makes sense to focus on specific businesses in order to maximize a return on investment.

Thank you for the great content. It was a nice reminder of a few of the things I learned in university.

Regards,

Lawson

This is a very interesting article. To be honest I was completely unaware of the push for investors to act as stewards.

Worthwhile reading – the pyramid of success must be build on 1) the classic disciplines of investing and 2) long-term fiduciary duities to investors. Do send/write more papers on this topic as of great interest here in Europe. Thank Chris

One Trackback

[…] Topics & Investing Why Stewardship is Proving Elusive for Institutional Investors – via Harvard Law – As […]