Matteo Tonello is Director of Corporate Governance for The Conference Board, Inc. This post is based on a Conference Board Director Note by Sanjai Bhagat, Brian Bolton, and Ajay Subramanian, and relates to a paper by these authors discussed on the Forum here.

Selecting a new CEO is among the most delicate decisions a board of directors will ever face. The selection process is exposed to so many unknowns: personality, integrity, technical skills, and experience. Such intangibles are very hard to assess, let alone compare among candidates. In this evaluation, the education of a candidate may be one of the few pieces of information that is certain: the quality and relevance of that education may be debatable, but the simple facts are known and verifiable. To provide guidance to corporate boards on the validity of that indicator, this report analyzes data on the education of 1,800 individuals who served as CEOs of Standard & Poor’s Composite 1500 companies to determine the effect of education on CEO turnover and firm performance.

What makes a CEO great? Recent history has produced many successful CEOs, with vastly different backgrounds and personalities: Warren Buffett, Jack Welch, and Steve Jobs, to name just a few. As outsiders, we characterize these CEOs as “successful” because of the results they produce. Their companies have created new products, penetrated new markets, and provided substantial returns to investors and other stakeholders. It is easy to define a CEO as a great leader after his or her company has become successful; what is much more difficult is identifying a great candidate for CEO before that success has materialized.

Two of the most important responsibilities that boards of directors are tasked with are hiring and firing senior executives. The hiring process can be challenging because of the many uncertainties involved. It may be easy to talk about the intangible qualities that great CEOs should have—leadership, motivational skills, and strategic vision— but it is far more difficult to observe and measure these qualities. Different directors may see qualities from different perspectives; one director may view a CEO candidate as confident and self-assured, while another may consider the same candidate as arrogant and brash.

Reasonable directors can disagree. If evaluating such intangible characteristics is so difficult, what criteria should directors use to adequately perform this selection task? It is hard to object to Jack Welch’s description of what good business leaders do. In practice, however, picking future successful leaders is invariably, every time, a great challenge for the board.

Reasonable directors can disagree. If evaluating such intangible characteristics is so difficult, what criteria should directors use to adequately perform this selection task? It is hard to object to Jack Welch’s description of what good business leaders do. In practice, however, picking future successful leaders is invariably, every time, a great challenge for the board.

This report focuses on one observable CEO attribute— higher education—and considers its effect on firm performance, as well as the role it plays in the decisions to hire or dismiss a CEO.

Investigating the relationship between CEO education, CEO turnover, and firm performance yields some predictable and easily explainable results, but they are not without surprises:

- There is no consistent, long-term relationship between CEO education and firm performance. The analysis was extended to six measures of education and three measures of performance; however, it failed to find strong or reliable associations.

- There is no association between CEO education and the likelihood of a CEO experiencing disciplinary turnover. The dominant factor affecting disciplinary-turnover cases is poor past performance. If the firm (or the CEO) has underperformed, the CEO is likely to be fired, regardless of his or her educational background.

- Following cases of disciplinary turnover, bringing in a new CEO with an MBA leads to short-term improvements in operating performance, while bringing in a new CEO with a Master’s degree leads to weaker short-term operating performance. However, these changes are appreciated within a short period and do not persist over the long term.

- Following cases of disciplinary turnover, boards tend to hire a new CEO with the same education type as the former CEO. This finding is surprising and puzzling on two counts. First, as mentioned previously, there is no reason to value any specific type of education since it does not appear to be associated with superior performance. Second, and most curious, in cases where board members made a decision to remove an under-performing CEO, boards do not seek out a new CEO with a different education. They end up bringing in a new chief executive with the same educational background.

Measuring CEO Education

Just as it can be difficult for a board of directors to measure the intangible qualities of an individual aspiring to the CEO position, there is no completely objective way to measure the quality of an education. With this caveat in mind, this study used the 2008 U.S. News & World Report rankings to distinguish the quality of different programs. [1] The analysis was limited to six education categories (these classifications are not mutually exclusive, as many CEOs fall under several categories):

- 1. UG-Top20: Whether the CEO has an undergraduate degree from a Top 20 school.

- 2. MBA: Whether the CEO has an MBA.

- 3. MBA-Top20: Whether the CEO has an MBA from a Top 20 business school.

- 4. LAW: Whether the CEO has a law degree.

- 5. LAW-Top20: Whether the CEO has a law degree from a Top 20 law school.

- 6. MASTER: Whether the CEO has a Master’s degree (usually in a technical, non-business discipline).

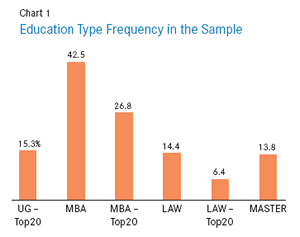

Chart 1 shows the frequency of each of these six education types in the sample of 14,596 CEO years: just over 15 percent of the CEOs graduated from a Top 20 undergraduate program, whereas more than 40 percent have an MBA, and about 14 percent have a law or Master’s degree.

Chart 1 shows the frequency of each of these six education types in the sample of 14,596 CEO years: just over 15 percent of the CEOs graduated from a Top 20 undergraduate program, whereas more than 40 percent have an MBA, and about 14 percent have a law or Master’s degree.

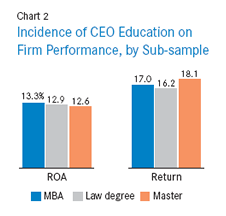

As stated previously, the central question in the study was whether the education of a CEO is related to firm performance. Chart 2 shows the incidence of CEO education on firm performance in three different samples—the full sample, the sample of firms with MBA CEOs, and the sample of firms with law degree CEOs—and using two different performance measures: annual operating performance (ROA) and stock market performance (Return; using both annual stock return and Tobin’s q, an estimate of the relative market value of assets). [2]

Chart 2 shows that firms with CEOs holding an MBA performed better than those with CEOs holding a law degree. However, many factors could also be contributing to these differences (firm size, industry, capital structure, risk exposure, CEO ownership, and age and tenure), which explains why the relationship had to be investigated further using a multivariate regression analysis (MRA), a technique for modeling and investigating several variables when the focus is on the relationship between a dependent variable (e.g., education) and one or more independent variables (e.g., firm size, industry, capital structure and the other factors mentioned above). Regression analysis facilitates the understanding of how the typical value of the dependent variable changes when any one of the independent variables is varied, while the other independent variables are held fixed. [3] (For more information about how the study was conducted, see the “Methodology” sidebar below.)

Chart 2 shows that firms with CEOs holding an MBA performed better than those with CEOs holding a law degree. However, many factors could also be contributing to these differences (firm size, industry, capital structure, risk exposure, CEO ownership, and age and tenure), which explains why the relationship had to be investigated further using a multivariate regression analysis (MRA), a technique for modeling and investigating several variables when the focus is on the relationship between a dependent variable (e.g., education) and one or more independent variables (e.g., firm size, industry, capital structure and the other factors mentioned above). Regression analysis facilitates the understanding of how the typical value of the dependent variable changes when any one of the independent variables is varied, while the other independent variables are held fixed. [3] (For more information about how the study was conducted, see the “Methodology” sidebar below.)

CEO education and long-term firm performance. The objective of the regression analysis was to determine firm and CEO characteristics—especially CEO education— that are associated with superior firm performance, as measured by both ROA and stock market performance.

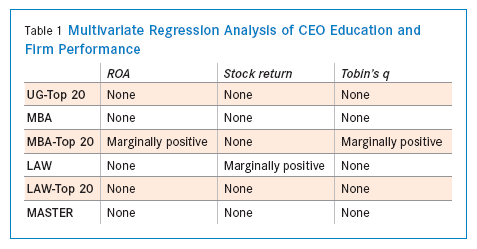

In all, 18 different regressions were run—one for each of the six types of CEO education and the three types of performance. As Table 1 shows, none of the 18 relationships appear to have strongly significant effects on firm performance, while three show a slightly marginal significance (in this case, “marginal” means a statistical significance between 5 and 10 percent).

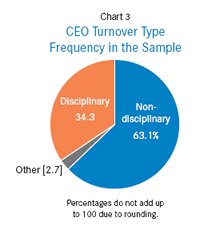

CEO education and CEO turnover. The average CEO tenure in the sample is 8.4 years. CEOs may leave for many reasons—among the most important, they may choose to retire (non-disciplinary turnover) or they may be fired for firm under-performance (disciplinary turnover). The study identified more than 2,600 cases of CEO turnover between 1993 and 2007. For each, press releases and other publicly available information were reviewed to determine the nature of the turnover. Some cases appeared straightforward: “retiring to spend more time with grandchildren, consistent with the succession plan we announced 3 years ago.” Others were less clear: “resigned to pursue other interests.” (See box below.) Chart 3 shows the incidence of different classifications of CEO turnover from the sample.

CEO education and CEO turnover. The average CEO tenure in the sample is 8.4 years. CEOs may leave for many reasons—among the most important, they may choose to retire (non-disciplinary turnover) or they may be fired for firm under-performance (disciplinary turnover). The study identified more than 2,600 cases of CEO turnover between 1993 and 2007. For each, press releases and other publicly available information were reviewed to determine the nature of the turnover. Some cases appeared straightforward: “retiring to spend more time with grandchildren, consistent with the succession plan we announced 3 years ago.” Others were less clear: “resigned to pursue other interests.” (See box below.) Chart 3 shows the incidence of different classifications of CEO turnover from the sample.

Non-disciplinary turnover. In September 2002, Philip Satre announced his intention to retire as CEO of Harrah’s Entertainment, after 18 years as CEO. Satre stepped down four months later, on January 1, 2003, and was succeeded by Gary Loveman, who was, until then, Harrah’s chief operating officer. Satre stayed with Harrah’s as chairman of the board through 2004, when Loveman became CEO and chairman. [a] “As CEO, I’ve achieved the goals I set for myself. It’s now time for Gary to take Harrah’s to the next level,” [b] Satre said in September 2002.

Disciplinary turnovers On January 9, 2003, Williams-Sonoma announced that CEO Dale Hilpert “is leaving the Company,” effective immediately. Board Chair Howard Lester commented, “we wish him well in his future endeavors.” [c] He was succeeded by Edward Mueller, a Williams-Sonoma director since 1999 who had been in a senior management position with SBC Communications. Less than four years later, on July 14, 2006, Mueller retired as CEO and was succeeded by Lester. Lester had been chairman since 1986 and previously served as CEO from 1979 to 2001, when he was replaced by Hilpert. After retiring as CEO, Mueller did stay with Williams-Sonoma as a non-executive director for 10 months, but “agreed to not seek or accept nomination as a member of the Board of Directors following the expiration of his current term that ends as of our 2007 Annual Meeting” in May 2007, according to the 2007 proxy statement.

On the surface, each of these events could be non-disciplinary. However, the very short tenures and the return of the former CEO were immediately perceived by the public as yellow flags. Additional secondary sources revealed that both turnover events were, in fact, the result of Lester being dissatisfied with performance. According to the Wall Street Journal:

With Mr. Mueller and his predecessor, Dale Hilpert, Mr. Lester remained chairman and a powerful force in running the company, even taking charge recently of the Williams- Sonoma chain of kitchen stores. Mr. Mueller “thought that he was going to be the real CEO, but he wasn’t,” an acquaintance of Mr. Lester’s says. Messrs. Hilpert and Mueller “were both shadow CEOs,” this person added. [d]

Three years later, regarding Mueller’s resignation, Lester said, “I was there certainly during Ed’s time because Ed wanted me to be there. Having said that, do I know that it’s always hard for another CEO to have me around every day? Certainly it is.” [e]

[a] Harrah’s Entertainment, Inc., press release, October 20, 2004, available at http://investor.harrahs.com.

[b] Harrah’s Entertainment, Inc., press release, September 4, 2002.

[c] Williams-Sonoma, Inc., press release, January 9, 2003, available at www.williams-sonomainc.com.

[d] Amy Merrick and Joann S. Lublin, “Chain’s Ex-CEO Retakes the Job — Once Again,” Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2006.

[e] Abigail Goldman and Leslie Earnest, “Chairman to Resume Helm at Retailer,” Los Angeles Times, July 12, 2006.

A second MRA was then conducted to determine the role that CEO education, among multiple factors and circumstances, plays in the CEO turnover process. This new analysis was performed controlling for firm and CEO characteristics (such as size, ownership, and age) as well as the type of CEO departure to identify the role that CEO education might play in disciplinary turnover separate from the role it might play in non-disciplinary turnover.

In addition, this new MRA relied only on one measure of firm performance—past stock return—since shareholders and directors are more likely to associate past stock return with the CEO’s abilities. If shareholders are disappointed with the performance of the firm and its CEO, it is most likely due to poor stock returns rather than to accounting or other measures of performance.

The conclusion of the analysis is that there is no correlation between CEO education in general (and education type in particular) and disciplinary CEO turnover events. Even though there is weak evidence that CEOs with a Top 20 law degree are less likely to be fired (and even weaker evidence that CEOs with a Top 20 undergraduate degree are more likely to be fired following poor performance), such an evidence level should be deemed statistically insignificant.

Despite this important observation, in all analyses of CEO departures, poor past firm performance dominates as the firm characteristic most highly associated with the incidence of disciplinary turnover. CEO education does not matter in the disciplinary decision; what ultimately matters is company under-performance.

New-CEO education and short-term firm performance. From a board of directors’ perspective, each case of disciplinary CEO turnover involves two important decisions: whether to let the CEO go and who to hire to replace the departed CEO. Poor past performance can help make the first decision relatively straightforward; nothing, however, is likely to simplify the replacement decision.

To better understand this replacement decision, the next phase of this analysis focuses on what happens to firm performance once the new CEO is in place—that is, what impact does the education of the new CEO have on short-term changes in firm performance? Obviously, the board of directors hires the new CEO hoping that he or she will lead to superior firm performance—in the long term, if not in the short term. And, as the first phase of the analysis confirmed, the choice of CEO does not have a significant impact on long-term firm performance.

To study the short-term performance, this new phase of the analysis focused on the change in performance, based on education, during the new CEO’s first year in office. In addition, since stock-market value appears to be an unreliable measure of short-term performance, this new analysis relied on operating performance (ROA) only. As before, the new analysis consisted of a MRA, controlling for firm and CEO characteristics.

When limited to firms that experienced disciplinary turnover, the analysis led to a few consistent results:

- Firms in which the new CEO holds an MBA or an MBA from a Top-20 business school showed clear signs of significant short-term improvements in operating performance.

- Weaker operating performance in the short-term was observed in firms in which the new CEO has a Master’s degree in a technical, non-business discipline.

This finding might be explained by the fact that CEOs with an MBA are more bottom-line oriented and focused on short-term approaches to improving the financial statements (for example, through layoffs and other cost-cutting measures). Chief executives with an education in technology-related specialties could be more investment-oriented and inclined to take business decisions that, when evaluated exclusively in the short-term, hurt the bottomline. However, as indicated earlier, neither of these effects appeared to be long-lasting, with no type of CEO education proven to be consistently associated with superior longterm firm performance.

This report is based on the analysis of data regarding 1,800 individuals who served as CEOs of Standard & Poor’s Composite 1500 companies (i.e., large, U.S.-based companies from all industries) between 1992 and 2007. Each of the CEOs in the study sample was observed over a period of (on average) eight years to evaluate the relationship between CEO education, CEO turnover, and firm performance. [a] Collectively, this amounts to the observation of 14,596 CEO years. The CEO education information and the CEO turnover information were hand-collected, [b] while firm financial performance information was obtained from publicly available data sources. [c] The objective of the study was to answer the following questions:

- 1. Is there a relationship between superior firm performance and CEO education?

- 2. Does CEO education have any influence on CEO turnover?

- 3. Following cases of CEO turnover, do CEOs with different education types help produce improved performance?

- 4. What role, if any, does the education of a candidate to the CEO position play in the board’s hiring decision?

For the purpose of this study, a multivariate regression analysis (MRA) was used to understand the general relationship between CEO education and firm performance.

The regression was run controlling for multiple factors:

- Firm characteristics: including size, risk, and debt

- CEO characteristics: including age, tenure and stock ownership

- General characteristics: including industry and time period.

A second MRA was then conducted to determine the role that CEO education, among multiple factors and circumstances, plays in the CEO turnover process. This new MRA was divided in two parts:

- 1. A baseline analysis, including past firm performance (as well as other firm and CEO characteristics, such as firm size, capital structure, CEO age and tenure, and industry performance) as a predictor of turnover — but not including CEO education. In this first phase, past stock return is far and away the most important catalyst for disciplinary CEO turnover: the CEO is more likely to get fired if the firm has performed poorly.

- 2. A set of analyses adding the CEO education variables illustrated above to see if any of the six types of education are associated with greater likelihood of disciplinary CEO turnover.

[a] Most CEOs in the sample represent several years of observations. The average tenure of the CEOs in the sample is just over eight years and the frequency of CEO turnover events is about 10 percent for all companies in the sample.

[b] Essential CEO turnover information is available from Compustat’s Execucomp database. In addition, company press releases and other public sources were individually reviewed to determine why the CEO turnover occurred and to distinguish between cases of disciplinary and non-disciplinary turnover.

[c] Sources include Compustat for financial statement information; the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) for stock price information; and RiskMetrics/ISS for board and director information.

CEO education and CEO selection. As mentioned, while the decision to dismiss a CEO is usually based on observable under-performance, the decision to hire a new chief executive tends to be less straightforward. The board’s task is to find an individual with leadership, interpersonal and motivational skills, a proven track record of success, and the commitment to improving competitive advantage and adding value to the business—an incredibly complex task that board members are expected to conduct with only limited and often indirect knowledge of the candidates. While the board is obviously more familiar with internal candidates, it might hesitate to assign these responsibilities to an individual who has not yet performed in the chief executive capacity. While external candidates are likely able to document their top leadership skills from their experience at other firms, the board might be unsure whether they can adapt to the new firm’s culture, industry, or business strategy. Inevitably—regardless of how much information is gathered about each candidate, how many consultants are engaged, and how many interviews are conducted—board members won’t be able to dissipate the many uncertainties about whether a certain candidate is the right person for the job.

In a process exposed to so many unknowns, the candidate’s education may be one of the few pieces of information that is certain. The quality and relevance of that education may be debatable, [4] but the simple facts regarding such education are known and verifiable. In particular, because of the reputation surrounding a certain school or degree type or the accomplishments in studying certain disciplines, board members could be influenced by this piece of information and use it as an indicator of the candidate’s future performance as CEO—even though the candidate is likely to have obtained those credentials more than 20 or 30 years before.

The final phase of the analysis then considered whether education plays a role in the board’s choice of a new CEO. In particular, the sample of CEO turnover cases was first used to investigate the association between the education of the former CEO and the education of the new CEO.

This process was conducted for both disciplinary and nondisciplinary subsets of the sample, and repeated for both the former and new CEO for all six possible education types (for a total of 72 analyses). Specifically, the research question was: “Given that the former CEO had education X, is the new CEO more or less likely to have education X or Y?”

As discussed, the sub-sample of non-disciplinary turnover cases includes situations in which the former CEO left the company willingly, often based on a succession plan that had been in place for years and not due to under-performance or dissatisfaction by the board. To the extent that the board somehow associated the former CEO with any type of education—and there is no way to conclude that such association did take place in any of the cases examined—it would logically follow that the board was, at worst, satisfied with the former CEO’s education type. For this reason, it was no surprise to find either a positive correlation or no correlation whatsoever between the education types of the former CEO and the new CEO. Specifically, the analysis showed that in situations in which the former CEO held a Master’s degree, there is a higher than average likelihood that the new CEO also would have a Master’s degree. Similarly, when the former CEO had a Top-20 law degree, the analysis showed a higher than average likelihood that the new CEO would also have earned a Top-20 law degree. Once again, this finding is all but surprising, considering the circumstances of the former CEO’s departure—in good times, boards replace a departing CEO with someone with similar credentials or with the best person for the job, regardless of considerations on his or her educational background.

The more interesting analysis concerns board decisions following cases of disciplinary turnover—that is, situations in which the succession was prompted by some friction or dissatisfaction between the board and the former CEO. In some of the cases, the CEO was terminated because of poor performance or inappropriate conduct; in others, the CEO resigned to pursue another position after the board refused to grant a compensation package that it could not justify. In either case, the separation was likely not on the best of terms. In these disciplinary turnover situations, it is reasonable to expect that, while selecting the new CEO, the board would want to change leadership style and culture, ultimately taking in greater consideration not only the prior work experience but also the education background of candidates vis-à-vis the educational background of the former CEO.

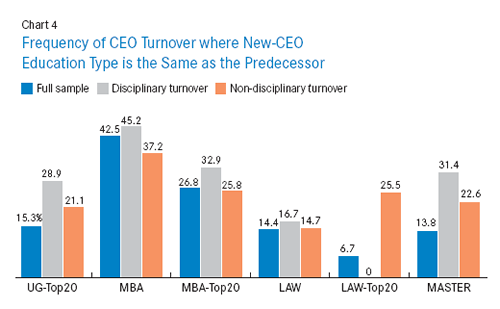

Instead, the analysis brought the opposite conclusion— boards frequently replace a CEO with a new chief executive holding the exact same education type of the departing one. Once again, the analysis covered 36 situations of former-CEO and new-CEO education type. Out of those 36 analyses, 10 showed statistically significant associations. In five cases out of those 10, the Top-20 undergraduate degree held by the new CEO appeared to be exactly the same as the one of the former CEO; and the same before-after relationship resulted with respect to four of the other five education types: MBA, MBA-Top20, Law degree, and Master’s. The only type of new-CEO graduate degree that appeared not correlated with the same type of former- CEO graduate degree was Law-Top20. In conclusion, these findings are strong evidence that boards do value the education type or background of the new CEO candidate, but in a way that is counter-intuitive. Ultimately, boards still tend to replace the CEO they ousted with a new CEO who has a very similar educational background.

Chart 4 compares the propensity of firms to hire a CEO with an education type that is the same of his or her predecessor. It shows that 15.3 percent of all CEOs have a UG-Top20 degree. Following disciplinary turnover involving a CEO with a UG-Top20 degree, 28.9 percent of the new CEOs also have a UG-Top20 degree. Following non-disciplinary turnover involving a CEO with a UG-Top20 degree, 21.1 percent of the new CEOs also have a UG-Top20, more than the sample average, but less than in the cases of disciplinary turnover. In five of the six cases, disciplinary turnover is greater than the sample average, indicating that the likelihood of hiring a CEO with education X is greater following the dismissal of a former CEO who also had education X. The lone exception is following disciplinary turnover involving a Law-Top20 CEO, where no new CEOs with a Law-Top20 degree were hired to replace an ousted CEO. Consistent with the regression analyses, the comparisons of non-disciplinary turnovers are less dramatic.

The question then becomes “why do boards look to replace a former CEO with a new CEO who has very similar education credentials?” Several speculations are possible:

- Boards tend to conclude that leading their firms requires a specific skill set that only a certain type of education can provide (e.g., the analytical skills often associated with a law or engineering background). However, if this was the case, the analysis should have shown similar former-new direct relationships in the sample of non-disciplinary turnover cases.

- Boards tend to think that choosing a new CEO with the same education type as the departing one would exonerate them from being blamed for the wrong education-based choice made with the former CEO. In other words, to prove that the education type had nothing to do with the disappointment regarding the former CEO, the board would bring in a new CEO with a similar education type. In essence, their reasoning would be that the individual, not the hiring model, was defective.

- The decision could depend on the emergency, unplanned nature of the disciplinary succession. In cases of non-disciplinary turnover, a succession plan has often been developed over a period of months or years. The board and the departing CEO have the time and resources to thoroughly evaluate all possible internal and external candidates. In cases of disciplinary turnover, boards may not have the luxury of time, resources, or planning, and are often forced to make an emergency decision and conclude that the education of the successor should be of the same type as his or her predecessor, because, unlike other CEO characteristics (personality, integrity, and cultural fit), education is one of the few pieces of information that is certain in a rushed, unplanned process.

- The decision could be affected by the composition of the board. There are still many situations in corporate America in which the CEO plays an influential role in filling the current board, with the result being that the CEO and the members of the board have similar backgrounds and value equally similar background. When that CEO departs, the board members tend to choose a new one with the same characteristics that were at the basis of their own selection as board members.

- Finally, the decision could have to do with the uniformity of the pool of candidates, as the industry in which the company operates might naturally attract candidates with the same educational background as the departing CEO’s.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no strong evidence of a relationship between CEO education and firm performance, while there is weak—and, perhaps, statistically insignificant—evidence that the leadership of a CEO having a MBA degree from a Top 20 business school enables better operating performance and Tobin’s q.

Endnotes

[1] Other rankings, such as BusinessWeek’s business school rankings, are very similar and produce similar results.

(go back)

[2] ROA is calculated as operating income before depreciation to total assets. Return is the annual compound stock return. Tobin’s q is the ratio of a firm’s market value to the replacement cost of its assets; market participants often use this ratio as an economic indicator of investment opportunities.

(go back)

[3] D.V. Lindley, “Regression and Correlation Analysis,” New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 1987, Volume 4, pp. 120–23.

(go back)

[4] Steve Jobs and Bill Gates both dropped out of college. Jack Welch received a Ph.D. in chemical engineering. While this degree may have been instrumental in his initial success at General Electric, it is difficult to see its relevance to his more than 20-year tenure as CEO. There are too many other examples to list here.

(go back)

Print

Print

3 Comments

Thank you for this analysis. I am wondering if the term ‘education” you used has been too narrowly defined. What about additional executive education the leader has sought out to refine / complement his/her skillset ? What about the “education” brought by having been exposed to other industries or strategic challenges ? What about the lessons learned from past failures for example ? You might find then a higher correlation to performance. Great CEOs do share some common personality characteristics, but who has inspired, coached and taught them also has a great influence on their success.

These results are interesting, particularly the finding that boards tend to replace the CEO with someone who has the same type of education. I agree with Ms. Metayer that continuing one’s education after schooling may modify the results. Knowledge and insight move forward after one completes her degree. How does a CEO’s willingness to learn and improve correlate with performance?

You may want to look at our research on this topic as well….. It’s a comprehensive analysis of F500 CEO credentials.

The Education of A Leader: Educational Credentials and Other Characteristics of Chief Executive Officers. Journal of Education For Business. 85: 209-217, 2010