Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at the Conference Board. This post is based on an issue of the Conference Board’s Director Notes series by Lorenzo Patelli, professor at the School of Accountancy of the University of Denver. This Director Note was based on a paper coauthored by Professor Patelli, available here.

Consistent with corporate social responsibility (CSR), firms strive to engage stakeholders through various initiatives aimed at fostering dialogue between managers and external stakeholders. Diverse forms of dialogue and broad involvement are critical to the success of stakeholder dialogue (SD) initiatives. This Director Notes describes the results of an international survey on 249 SD initiatives undertaken by firms in Germany, Italy, and the United States. The survey results highlight the limitation of current SD practices and identify a strong link between the national approach to corporate social responsibility and the firm approach to SD.

Firms seek the involvement of stakeholders in order to maximize the alignment of business activities with the interests of different organizational and social actors. [1] In particular, SD refers to all initiatives undertaken by firms to listen and communicate to stakeholders regarding a vast array of topics. [2] Many researchers have noted the positive effects SD is expected to produce:

- Continuous learning about the competitive environment by facilitating the emergence of new perspectives and organizational change through improved relationships. [3]

- Organizational cohesion by promoting participative decision-making and a stakeholder approach to strategic management. [4]

- Reduction of risk by enhancing the understanding of how external and internal actors perceive management’s actions. [5]

- Legitimization of decisions by fostering organizational trust and managerial accountability. [6]

Two conditions are needed to ensure SD effectiveness:

- 1. SD must rely on multiple forms of dialogue and comprehensive involvement of different categories of stakeholders. The benefits of SD can be fully exploited if SD initiatives enable firms to engage in a dialogue that is characterized by high interaction and diversity of concerns, and not simply the repetition of many initiatives.

- 2. SD must entail high involvement forms of dialogue to maximize its benefits. Some forms of dialogue that support the stakeholder involvement strategy are characterized by symmetric interaction between the firm and its stakeholders. Other forms support the stakeholder response strategy, which is characterized by asymmetric interaction between the firm and its stakeholders. The latter forms reduce the beneficial aspects of SD and its social responsible elements. [7]

Notwithstanding the theoretical support in favor of the implementation of SD practices, there is a noticeable lack of empirical evidence about how firms engage in a dialogue with stakeholders. The following section presents findings from an international survey, with special attention focused on what drives firms to undertake SD initiatives.

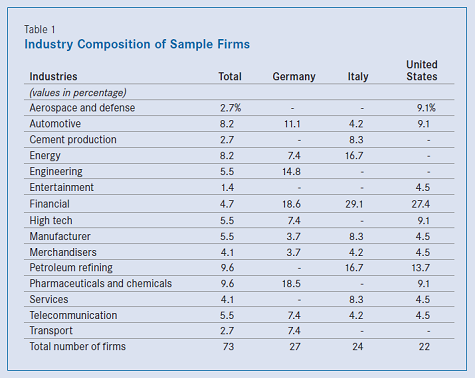

Methodology and OverviewInformation about SD initiatives was collected from the sustainability reports published in 2007 by each of the 50 largest firms by revenue in Germany, Italy, and the United States. Out of 150 firms, 92 firms (61.3 percent) published a sustainability report in 2007 in addition to their annual financial report, but only 73 reports provided information regarding SD initiatives. Table 1 shows the industries represented in the sample. Larger firms were found to be significant promoters of CSR practices, and these firms were also commonly associated with higher quality in sustainability reports. [8] Information about the form and frequency of the SD initiatives, the number and category of stakeholders involved, and the topics was collected for each firm. [9] Given the large firm size and economic advancement of the three countries, the number of sustainability reports is lower than expected. Also, the scarcity of such information indicates the lack of standardization of social disclosure. In fact, we found a relatively high proportion of the SD initiatives (14.6 percent) that address issues related to social disclosure. The recent diffusion of international rankings (e.g., accountability ratings) evaluating sustainability reports could create incentives to enhance social disclosure.

An International Approach

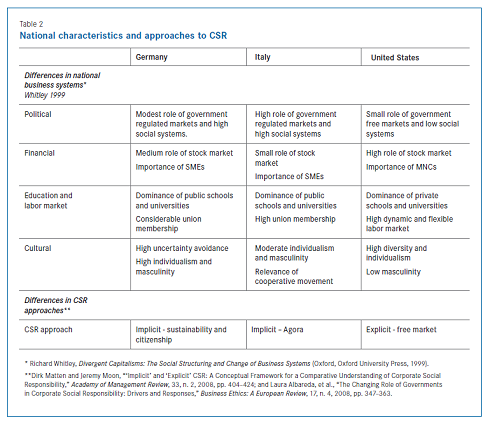

Germany, Italy, and the United States were chosen for three reasons. First, they are all large developed economies with a strong sensitivity to social responsibility issues, each driven by different motives. Second, despite their similarity in terms of significance for the global economic environment, different political, financial, educational, and cultural factors shape their respective national business systems in different ways. [10] Such differences are important to the interpretation of the empirical findings and reveal the drivers behind the decisions to engage in SD. Third, previous studies have shown that each of the three countries takes a different approach to CSR. In the United States, firms emphasized explicit elements of CSR, whereas the European firms emphasize different implicit elements of CSR. [11] The explicit approach to CSR indicates the deliberate disclosure of CSR actions and the firm’s strategy to communicate its decision to engage with stakeholders. CSR actions are the result of an explicit decision aimed at enhancing firm social and financial performance. In contrast, the implicit approach to CSR indicates rare and poor communication about CSR. CSR actions are not the result of a strategic decision, but they do represent the reaction to specific aspects of the national business system. [12] One aspect highlighted by several studies is the influence of national governments on CSR through public policy. [13] In Germany, the structure of corporate governance reflects the contribution of different stakeholders, and especially that of employees, to the business activities. The government plays a modest role, and public policies and corporate actions on CSR emphasize sustainable developments. The German approach to CSR is labeled the Sustainability and Citizenship model. In Italy, the government plays a fundamental role through nationalized businesses and high regulation. Public policies on CSR are formulated through the involvement of a diverse group of social actors. Dialogue and negotiation are the critical methods used to achieve consensus. The Italian approach to CSR is labeled the Agora model. [14] Table 2 summarizes the major characteristics shaping the national business environments in the three countries and the approaches to CSR in the three countries.

Characteristics of the SD initiatives

Quantity of SD

As shown in Panel A of Table 3, on average, German, Italian, and U.S. firms undertook 3.1, 4.4, and 4.8 annual SD initiatives, respectively, in 2007. Overall, firms undertook an average of four SD initiatives a year. Given the number of fundamental categories of stakeholder (i.e., five) and the narrow focus of SD on a single category of stakeholders, the figures indicate a fairly low volume of SD activities. Compared to German and Italian firms, U.S. firms reported a higher number of SD initiatives, consistent with the explicit approach to CSR. The average number of forms used per firm was more uniform across countries. However, this points to another limitation of current SD practice: concentration on few forms of stakeholder dialogue. Indeed, on average, firms used only 2.3 forms of SD. The benefits of the concentration on few forms depend on the firm’s specialization on specific techniques of interaction with stakeholders. The costs of the concentration on few forms of SD depend on the methodological and cognitive biases of the specific forms preferred by the firms. Moreover, the reliance on few forms of SD hinders the comprehensiveness of the dialogue and increases the likelihood important stakeholder concerns will be neglected. Similar to the average number of forms used, the average number of categories of stakeholders involved in the SD initiatives indicates a narrow focus. Overall, firms undertook SD initiatives with 2.4 categories of stakeholders, on average; this average was homogenous across countries. Regardless of nationality, a high proportion of the SD initiatives involved employees, while a limited proportion involved suppliers. However, the involvement by the other three categories of stakeholders (community, customers, and shareholders) varied significantly across countries. Compared to the firms in other countries, German firms reported a low percentage of SD initiatives involving shareholders, Italian firms reported a high percentage of SD initiatives involving customers, and U.S. firms reported a high percentage of SD initiatives involving communities. Panel A of Table 3 shows the international similarity of the average number of topics discussed. Overall, firms discussed an average of 2.4 topics (out of 12 groups of topics considered in the empirical analysis). In contrast to German firms, which reported a high dispersion of topics, Italian and U.S. firms focused their SD initiatives on three groups of topics: social disclosure, generic stakeholder needs, and strategy and performance.

Level of Involvement

An accurate appreciation of SD requires an examination of not only the number of initiatives, but also the variety of forms used to dialogue, and the breadth and number of stakeholder groups involved in SD initiatives. In order to better grasp the interaction of the dialogue initiated by the firms through SD initiatives disclosed in their sustainability reports, the seven categories of forms considered in the empirical survey were divided into two groups: stakeholder response and stakeholder involvement. The stakeholder response group contained conferences, contact points, interviews, and questionnaires and surveys; the stakeholder involvement group contained committees, focus groups, and forums. [15] Panel B of Table 3 shows the percentage of SD initiatives in the stakeholder involvement group. The percentage measures the average proportion of forms used by a firm that support the stakeholder involvement strategy. These forms enable firms to engage in an interactive analysis of stakeholders’ concerns and can lead to shared actions and decisions. The reciprocal percentage measures the average proportion of forms used by a firm to support the stakeholder response strategy. These forms limit the dialogue to a one-way interaction and allow firms to simply react to stakeholders’ concerns. Only stakeholder involvement forms enable firms to dialogue with their stakeholders in a manner that is capable of increasing mutual understanding of expectations and improving relationships.

Panel B of Table 3 reports low percentages of stakeholder involvement forms for each of the three national samples. These results indicate most of the SD initiatives relied on low-involvement forms consistent with the pursuit of the stakeholder response strategy. However, there are significant differences across countries regarding the categories of stakeholders involved in the SD initiatives. Only 20.9 percent of the initiatives undertaken by U.S. firms were in the stakeholder involvement group, while 29.5 percent of the initiatives undertaken by Italian firms were in the stakeholder response group. Specifically, U.S. firms tended to concentrate their use of stakeholder involvement forms on the dialogue with communities, whereas Italian firms relied on stakeholder involvement forms for the dialogue with different categories of stakeholders. Although the sample contained the same number of SD initiatives for Italian and U.S. firms, and a similar proportion of Italian and U.S. initiatives addressed employees’ concerns, the percentage of stakeholder involvement forms used in the dialogue with employees was remarkably different in the two national samples. In contrast to 31.3 percent in the Italian sample, only 4.2 percent of U.S. SD initiatives use involvement forms of dialogue. Overall, the results based on the distinction between stakeholder response and stakeholder involvement forms show that the SD initiatives of the firms studied were dominated by low involvement forms, independent of the category of stakeholders involved in the dialogue.

In order to further investigate the characteristics of the dialogue between firms and their stakeholders, the SD initiatives were divided into two categories that were based on the number of categories of stakeholders involved. SD initiatives addressing concerns of one category of stakeholders alone were categorized as mono-stakeholder SD initiatives; otherwise, the SD initiatives were categorized as multi-stakeholder. Panel B of Table 3 reports low percentages of multi-SD initiatives for each of the three national samples. In total, only 5.1 percent of the SD initiatives were multi-SD initiatives. However, there were differences across the national samples. The highest percentage of multi-SD initiatives was found in the Italian sample (8.6 percent), followed by the German sample (4.8 percent), and the U.S. sample (1.9 percent). The results reveal that Italian multi-SD initiatives tended to be undertaken with different categories of stakeholders, while German multi-SD initiatives tended to involve communities and U.S. multi-SD initiatives tended to involve shareholders. With regard to the number of categories of stakeholders, the findings indicated that firms tended to adopt a narrow focus in the dialogue with their stakeholders. That tendency was particularly present in the U.S. sample, suggesting an association between mono-SD initiatives and an emphasis on explicit elements of CSR.

Diversity of SD

Diversity of forms and diversity of stakeholders were measured using two indexes: the Form Diversity Index (FDI) and the Stakeholder Diversity Index (SDI). The FDI measures the variety of forms used by a firm to dialogue with stakeholders. An index value close to 1 (0) indicates high (low) diversity of forms (when analyzing FDI) or stakeholders (when analyzing SDI). Panel C of Table 3 shows that, on average, the FDI and SDI of the firms were 40.7 percent and 36.9 percent, respectively. These low percentages indicate that firms tended to focus SD initiatives on few forms and on few categories of stakeholders. Although they reported information about 294 SD initiatives overall, the 73 firms examined tended to use a limited number of SD forms and involved only a few categories of stakeholders. However, a cross-country analysis of the FDI and SDI revealed significant national differences. The highest values for both FDI and SDI (49.8 percent and 46.9 percent, respectively) were found in the Italian sample. The lowest values for both FDI and SDI (31.5 percent and 27.7 percent, respectively) were found in the German sample. These results show that the Italian firms studied were more likely to use different forms of dialogue with a diverse group of stakeholders than German and U.S. firms.

National Differences

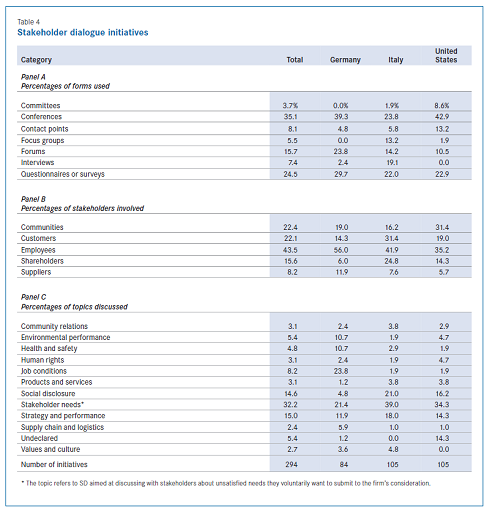

Germany

Table 4 shows the frequency of the different forms of SD. German firms undertook most of their SD initiatives through conferences. Two other recurrent forms of SD initiatives among the German firms were forums and questionnaire surveys. Contact points and interviews were rare, and committees and focus groups were not mentioned in any of the German firms’ sustainability reports. Overall, the German subsample was characterized by the low diversity of forms used for SD. Table 4 also provides descriptive statistics about the targeted category of stakeholders. Nearly 55 percent of the SD initiatives undertaken by German firms involved employees. The focus on employees was also observed in Italian and U.S. firms, but Germany reported the highest percentage of initiatives focused on employees. Unlike the Italian and U.S. subsamples, few of the German firms’ SD initiatives involved customers. Moreover, SD initiatives involving shareholders represented only 6 percent of the initiatives undertaken by German firms, whereas they were significantly more frequent among the Italian and U.S. subsamples. Finally, Table 4 reports the frequency of CSR issues addressed through the SD initiatives. In the German subsample, stakeholder needs and job conditions were the most frequently mentioned SD topics in the sustainability reports, consistent with the national focus on employees and the national corporate governance system. While stakeholder needs was also frequently reported by firms in the other countries, job conditions were rarely reported by firms in the Italian and U.S. subsamples. Only 4.8 percent of the SD initiatives undertaken by German firms dealt with social disclosure, suggesting a lack of concern with social reporting.

Italy

Based on the results reported in Table 4, Italian firms did not prefer a single form to dialogue with stakeholders, but instead pursued SD initiatives in a variety of other forms. In comparison to the German and U.S. subsamples, the use of interviews by Italian firms was very frequent. Interviews may offer an efficient communication channel for SD with members of labor and customer unions, who have great influence within the Italian business environment. Further, the small firm size and high ownership concentration characterizing Italian firms do not justify the organization of large conferences. Indeed, in the Italian subsample, conferences were less frequent than in the German and U.S. subsamples.

Most SD initiatives undertaken by Italian firms involved employees. In general, the dialogue was aimed at examining employee satisfaction and other work-related issues. Community stakeholders, customers, employees, and shareholders were usually involved in mono-stakeholder SD initiatives, while suppliers were more often involved in multi-stakeholder initiatives. With regard to topics, Italian firms placed great emphasis on SD initiatives discussing social disclosure practices. Among the Italian subsample, 21 percent of the SD initiatives dealt with social disclosure—the second most frequent topic of SD. Italian firms engaged in SD to improve the robustness of social performance indicators and enhance the transparency and fairness of social reporting.

United States

As shown in Table 4, the most frequent form of SD in the U.S. subsample was conferences (8.6 percent). U.S. firms also frequently reported the use of questionnaire- based surveys. No U.S. firm reported the use of interviews for SD. As mentioned previously, U.S. firms in the study were typically large, public companies, and conferences and large questionnaire-based surveys seem to be the most appropriate SD forms to reach out to large groups of stakeholders. The frequency of contact points used for SD by U.S. firms is noteworthy: 13.2 percent of the SD forms for U.S. firms were contact points—the third highest percentage reported in Table 4 for the U.S. subsample. Relative to the other SD forms, contact points were less formalized and collegial, supporting the personalized and individualistic approach of U.S. firms to CSR. Table 4 also reveals that most SD initiatives of U.S. firms involved employees or community stakeholders. While the focus on employees was consistent with that found in the German and Italian subsamples, the focus on community was unique to the U.S. firms, suggesting that the primary motive of the U.S. SD initiatives was the social welfare of the community. Suppliers were the least involved category of stakeholders, indicating that the U.S. firms lacked a supply management perspective in their CSR practice.

Table 4 shows the wide distribution of topics in the SD initiatives reported by U.S. firms. The quality of the disclosure seems to be poorer than that registered in Germany and Italy, as indicated by the high percentage of SD addressing undeclared issues. A remarkable portion of U.S. firms’ SD initiatives (16.2 percent) were undertaken to assess social disclosure, but this result may be explained by the adoption of social disclosure models rather than because of any real concern of the U.S. firms about social reporting. It is also interesting to note the percentage of SD initiatives addressing human rights issues. The large size and international nature of many U.S. firms in the sample may direct CSR toward the social consequences of globalization.

Approach to Stakeholder Dialogue

The overall number of SD initiatives per firm ranged from 22 to 1, with an average of 4. Firms tended to use few forms of dialogue and involved few categories of stakeholders. Conferences and large questionnaire-based surveys were the preferred form of SD among the group. Committees and focus groups were rarely used, suggesting a scarce interest for informal and personal forms of dialogue. The use of low-involvement forms of dialogue can reduce the benefits of SD. Moreover, it may indicate that through SD, firms use stakeholder needs as a vehicle to pursue their own interests. The majority of SD initiatives involved only one category of stakeholders. The dominance of mono-stakeholder SD initiatives suggests that firms tended to act as leaders of a one-to-one SD, and not as contributors of broad dialogue involving multiple stakeholder perspectives.

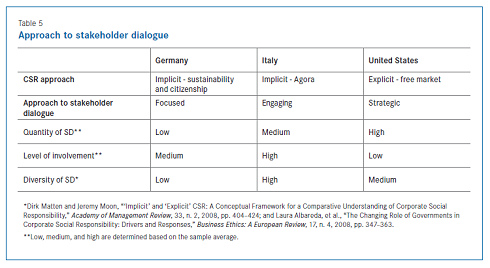

As shown in Table 5, companies in all three countries most frequently involved employees in SD initiatives, followed by customers in Italy, and by community stakeholders in Germany and the United States.

German firms tended to undertake fewer SD initiatives characterized by low diversity of forms used and stakeholders involved. German firms also selected the key category of stakeholders and concentrated their efforts on one form of dialogue. [16] The dispersion of topics discussed through the German SD initiatives seems to indicate that different SD initiatives were undertaken to address specific issues, instead of an unstructured and open exchange between firms and their stakeholders. This approach to SD is consistent with the Sustainability and Citizenship approach to CSR, which emphasizes implicit elements of CSR in reaction to public policies. In particular, public policies in Germany are aimed at fostering awareness of citizenship among firms through incentives and other mechanisms of social market economy. Therefore, SD by German firms is based on a focused approach, achieved through a rational selection of forms and categories of stakeholders. As a result, SD of German firms appears to be an aspect of stakeholder management rather than a socially responsible SD. [17]

When compared with the overall sample, the SD initiatives of Italian firms were characterized by significantly higher-than-average levels of diversity of forms used and stakeholders involved. Moreover, Italian firms tended to undertake a higher-than-average number of multi-stakeholder initiatives and used more forms of stakeholder involvement (i.e., committees, focus groups, and forums). These results appear to indicate that the SD initiatives of Italian firms benefit from diverse processes of communication, numerous stakeholders, and a broad group of stakeholders, which are elements of high quality of dialogue. This approach to SD seems to be favored by the Agora model of CSR policy-making process. Wide participation in the process and deep attention to social values in the business culture promote an environment in which dialogue with multiple voices is used to reach consensus. Italian firms seem to replicate this policy-making approach in the design of their corporate SD initiatives. As a result, Italian SD initiatives appear to be designed according to a comprehensive, involving approach.

Finally, although they reported the highest number of SD initiatives, U.S. firms had a lower level of stakeholder involvement than the overall sample average. In particular, U.S. firms had an extremely low percentage of multi-SD initiatives, and the average number of forms used and topics discussed through the SD initiatives were the lowest in the sample. The combination of a high number of SD initiatives and a low number and diversity of forms and categories of stakeholders is consistent with the emphasis on explicit elements of CSR, which was dominant in the United States. In their sustainability reports, U.S. firms tended to provide information about many SD initiatives. However, the dialogue appeared to rely on a narrow set of forms and concentrated on few topics and a narrow group of stakeholders. An emphasis on the quantity, not the quality, of stakeholder engagement indicates a strategic approach to SD, which is the outcome of a tactical decision to approach certain categories of stakeholders with the purpose of increasing firm performance.

Conclusion

The findings offer several implications for managerial practices. The limited information disclosed in the sustainability reports and the concentration on certain forms of dialogues and categories of stakeholders reveals a need for improvement in social disclosure and SD practices. In particular, the promotion of CSR values and standards could generate additional incentives for firms that can lead to richer disclosure and more diverse SD initiatives. In addition, as explained by various streams of literature on CSR, firms must more ethically and consistently consider the importance of SD. The findings also revealed remarkable national differences. Characteristics of national business systems are associated with the firm approach to SD, and explain differences between SD practices in Germany, Italy, and the United States.

Due to differences across countries, for example, in terms of legislation and corporate governance structures, attempts to create universal principles and guidelines for CSR may be misguided. [18] Hence, multinational firms should not design their SD practice in a centralized and hierarchical way, but they should initiate an international dialogue, taking into consideration whether their subsidiaries operate in a national business system that favor a more focused, involving, or strategic approach to SD.

Endnotes

[1] André Habisch and Jeremy Moon, “Social Capital and Corporate Social Responsibility,” in J. Jonker and M. de Witte (eds.), The Challenge of Organising and Implementing CSR (London, Palgrave 2006), pp. 63–77.

(go back)

[2] Jon Burchell and Joanne Cook, “It’s Good to Talk? Examining Attitudes Towards Corporate Social Responsibility Dialogue and Engagement Processes,” Business Ethics: A European Review, 15, no. 2 , 2006, pp. 154–170.

(go back)

[3] Stephen L. Payne. and Jerry M. Calton, “Towards a Managerial Practice of Stakeholder Engagement: Developing Multi-Stakeholder Learning Dialogues,” in S. Sutherland Rahman, S. Waddock, J. Andriof and B. Husted (eds.), Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking: Theory, Responsibility, Engagement (Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing, 2002).

(go back)

[4] Harry J. Van Buren III, “If Fairness is the Problem, Is Consent the Solution? Integrating ISCT and Stake-Holder Theory,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 11, n. 3, 2001, pp. 481– 499.

(go back)

[5] Jamie R. Hendry, “Stakeholder Influence Strategies: An Empirical Exploration,” Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 2005, pp. 79–99.

(go back)

[6] Marc J. Epstein and Marie-Josee Roy, “Improving Sustainability Performance: Specifying, Implementing and Measuring Key Principles,” Journal of General Management, 29, n. 1, 2003, pp. 15–31.

(go back)

[7] Michelle Greenwood, “Stakeholder Engagement: Beyond the Myth of Corporate Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 2007, pp. 315–327.

(go back)

[8] David Hess, “The Three Pillars of Corporate Social Reporting as New Governance Regulation: Disclosure, Dialogue and Development,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 18, n. 4, 2008, pp. 447–482.

(go back)

[9] Kim Davenport, “Corporate Citizenship: A Stakeholder Approach for Defining Corporate Social Performance and Identifying Measures for Assessing It,” Business and Society, 39, no. 2, June 2000, pp. 210–219.

(go back)

[10] Richard Whitley, Divergent Capitalisms: The Social Structuring and Change of Business Systems (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

(go back)

[11] Dirk Matten and Jeremy Moon, “‘Implicit’ and ‘Explicit’ CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility,” Academy of Management Review, 33, no. 2, 2008, pp. 404–424.

(go back)

[12] Laura Albareda, et al., “The Changing Role of Governments in Corporate Social Responsibility: Drivers and Responses,” Business Ethics: A European Review, 17, no. 4, 2008, pp. 347–363.

(go back)

[13] Reinhard Steurer, “The Role of Governments in Corporate Social Responsibility: Characterising Public Policies on CSR in Europe,” Policy Sciences, 43, no. 1, 2010, pp. 49–72.

(go back)

[14] Laura Albareda, et al., “The Government’s Role in Promoting Corporate Responsibility: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and UK From the Relational State Perspective,” Corporate Governance, 6, no. 4, 2006, pp. 386–400.

(go back)

[15] Mette Morsing and Majken Schultz, “Corporate Social Responsibility Communication: Stakeholder Information, Response and Involvement Strategies,” Business Ethics: A European Review, 15, no. 4, 2006, pp. 323–338.

(go back)

[16] Jamie R. Hendry, “Stakeholder Influence Strategies: An Empirical Exploration,” Journal of Business Ethics, 61, September 2005, pp. 79–99.

(go back)

[17] R. Edward Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman Publishing Inc., 1984).

(go back)

[18] Isabelle Maignan and David A. Ralston, “Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from Businesses’ Self-Representations,” Journal of International Business Studies, 33, no. 3, 2002, pp. 497–514.

(go back)

Print

Print