The following post comes to us from Adam S. Hakki, partner and global head of the Litigation Group at Shearman & Sterling LLP, and is based on a Shearman & Sterling client publication. The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Marked by leadership changes, high-profile trials, and shifting priorities, 2013 was a turning point for the Enforcement Division of the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC” or the “Commission”). While the results of these management and programmatic changes will continue to play out over the next year and beyond, one notable early observation is that we expect an increasingly aggressive enforcement program.

Introduction

Since her swearing in as Chair of the SEC on April 10, 2013, former United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York Mary Jo White has repeatedly emphasized the importance of a robust Enforcement Division. As Chair White told The Wall Street Journal in June: “The SEC is a law-enforcement agency. You have to be tough. You have to try to send as strong a message as you can, across as broad a swath of the market as you regulate.” That is likely why, when choosing the Enforcement Division director, White turned to George Canellos (already Acting Director of the Division) and Andrew Ceresney, two former federal prosecutors from her days as United States Attorney. Similarly, beyond the home-office, former federal prosecutors have been appointed to lead some of the SEC’s regional offices. In fairness, the trend towards a quasi-criminal enforcement regime began under the SEC’s prior leadership, when then-SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro appointed Robert Khuzami to head the Enforcement Division in the aftermath of the Madoff scandal; now, it appears the change of emphasis is here to stay.

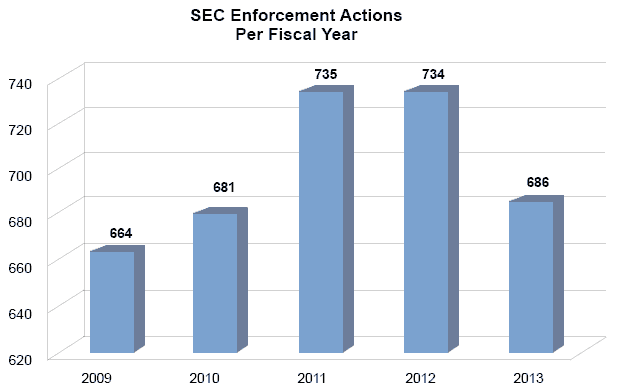

As illustrated in the chart below, the SEC filed 686 enforcement actions in FY2013, a decrease from FY2011 and FY2012, when the SEC filed 735 and 734 enforcement actions, respectively. Of these 686 cases, 132 were delinquent filing actions. Consequently, FY2013, based on the SEC’s own statistics, appears to be the Division’s least productive year since 2006. However, one should not take too much from these numbers, as the SEC also announced that there is a 20 percent increase in the number of formal orders of investigations issued by the Enforcement Division.

Source: SEC Press Release 2013-264, SEC Announces Enforcement Results for FY 2013 (Dec. 17, 2013)

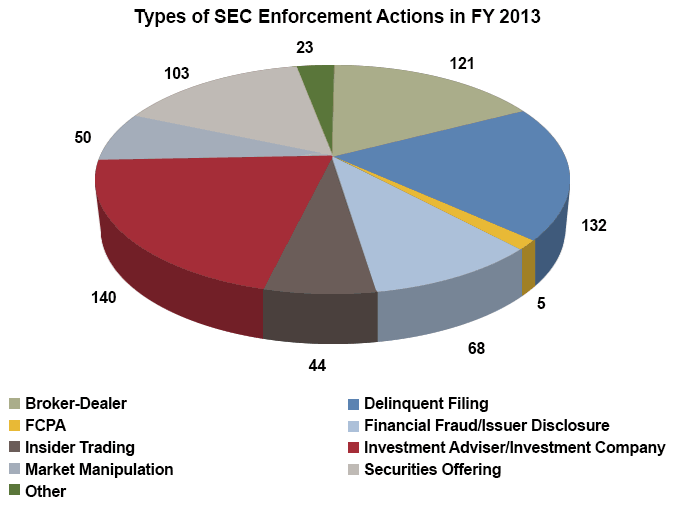

The distribution of cases among the Enforcement Division’s filing categories remained relatively stable in 2013. Only three categories of SEC actions showed an increase in the number of filings—actions related to (i) delinquent filings, (ii) market manipulation, and (iii) securities offerings. Meanwhile, filings in all other categories decreased, with the number of Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) actions experiencing the steepest decline, from 15 actions in FY2012 to five in FY2013, and the number of insider trading actions dropping from 58 to 44.

Source: SEC Press Release 2013-264, SEC Announces Enforcement Results for FY 2013 (Dec. 17, 2013)

Notwithstanding that the SEC filed fewer cases in FY2013, it obtained record civil penalties, disgorgement, and prejudgment interest. According to the SEC, “[t]he $3.4 billion in disgorgement and penalties resulting from [the actions concluded in FY2013] is 10 percent higher than FY2012 and 22 percent higher than FY2011, when the SEC filed the most actions in agency history.”

More than the figures, however, 2013 may be remembered for the high-profile trials and cases the SEC brought or concluded throughout the year. Whether winning big or losing big, the SEC demonstrated that the Enforcement Division is not afraid to “aggressively deploy litigation resources to maximize the deterrent impact of enforcement actions.”

In this memorandum, we address these cases, as well as the key policy and priority shifts announced by the SEC’s new leadership in 2013.

New Enforcement Division Priorities: A “Broken Windows” Policy

The Enforcement Division’s key priorities have begun to move away from pursuing securities violations that contributed to the financial crisis and which have for several years consumed a substantial percentage of the Enforcement Division’s resources. Indeed, in a speech on October 9, 2013, Chair White explained the Commission’s current thinking as follows:

- We want you to start thinking that every issue you face in the SEC’s space is a very important one. One of our goals is to see that the SEC’s enforcement program is—and is perceived to be—everywhere, pursuing all types of violations of our federal securities laws, big and small.

- The underpinning for this strategy was outlined in an article, which many of you will have read or heard of, titled, ‘Broken Windows.’ The theory is that when a window is broken and someone fixes it—it is a sign that disorder will not be tolerated. But, when a broken window is not fixed, it ‘is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.’

- The same theory can be applied to our securities markets—minor violations that are overlooked or ignored can feed bigger ones, and, perhaps more importantly, can foster a culture where laws are increasingly treated as toothless guidelines. And so, I believe it is important to pursue even the smallest infractions. Retail investors, in particular, need to be protected from unscrupulous advisers and brokers, whatever their size, and the size of the violation that victimizes the investor.

Chair White then laid out the key ways in which the SEC is now seeking to pursue this goal:

- Leveraging the strength of the SEC’s exam program, incentivizing individuals to step forward through the whistleblower and cooperation programs, collaborating more with other regulatory agencies, and increasing the use of technology in investigations;

- Focusing on deficient gatekeepers, whom the SEC views as responsible for self-policing the markets;

- Looking for the “broken windows” in our markets and not overlooking small violations or violations that do not involve fraud; and

- Prioritizing big and high-profile cases to send a strong message of deterrence to the industry and boosting the confidence of investors.

While none of these priorities are new, the emphasis is subtly changed. Clearly, there are no areas of the securities industry that can expect to be free of enforcement oversight, and Chair White has been cautious about singling out any one area for attention. But based on the Enforcement Division’s statements and track record in 2013, certain areas of focus remain apparent. Those include accounting and other financial reporting fraud; gatekeepers (including, particularly, auditors and lawyers); insider trading; compliance programs at broker-dealers and investment advisers; and the FCPA. These and other issues will be explored in this post.

Significant Trials

We begin with a review of the Enforcement Division’s 2013 trial record. Despite the apparent push by Chair White to bring more cases to trial (discussed at greater length below), the SEC’s trial record in 2013 left something to be desired. Although the Commission won a major victory in August against Fabrice Tourre, its 2013 trial record was also marred by several losses.

The case against Fabrice Tourre, a former Vice President with Goldman, Sachs & Co. (“Goldman”), was the Commission’s most significant trial victory in 2013. In April 2010, the SEC sued both Tourre and Goldman in a civil injunctive action, alleging that they committed fraud in connection with the structuring and sale of a collateralized debt obligation (“CDO”). While Goldman settled the allegations against it, without admitting or denying wrongdoing, by agreeing to pay a $535 million civil penalty and $15 million in disgorgement, Tourre opted for trial. After a two-week trial, the jury found Tourre liable on six of seven counts of fraud. To some, Tourre had, rightly or wrongly, become the face of the financial crisis. Consequently, the victory was undoubtedly a considerable relief to the SEC, which had tasked its chief litigator with personally trying the case. Since the Tourre trial, however, the news has been far less positive for the SEC.

In October, the SEC was handed a high-profile defeat in court when billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban was found not liable for insider trading in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. The SEC alleged that Cuban engaged in insider trading when he sold his stake in a Canadian internet company after the company’s CEO, Guy Faure, informed Cuban that the company was planning a private offering in public equity (PIPE), which would result in his stock being diluted. Allegedly, Cuban sold his stock to avoid a $750,000 loss. The case largely boiled down to the interpretation of a single unrecorded phone call between Cuban and Faure. But while Cuban testified at trial and adamantly defended himself, Faure, who lives in Canada, refused to travel to Dallas to testify, forcing the SEC to introduce his testimony via videotape. The jury ultimately rejected the SEC’s claims, apparently believing Cuban’s version of events. Against the backdrop of the government’s war on insider trading over the last few years, the Cuban case attracted significant public attention and marked a high-profile trial loss for the Commission.

Shortly after the Cuban loss, the SEC suffered another trial defeat in its long-running dispute with Steve Kovzan, the CFO of Kansas-based government website contractor NIC, Inc. In January 2011, the SEC filed a civil injunctive action against NIC, Kovzan, and three other NIC executives alleging that the defendants failed to disclose $1.18 million in executive perks, including use of a private company jet. NIC and the other charged executives settled, but Kovzan put the SEC to the task of proving its case in court. On December 2, after a three-week trial in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas, the jury found Kovzan not liable on all 12 of the SEC’s claims, including fraud and books and record charges.

In December, the SEC lost again in SEC v. Jensen. The SEC filed suit in July 2011 against Peter Jensen and Thomas Tekulve Jr., the former CEO and CFO, respectively, of Basin Water Inc., a company that remediates contaminated water. The SEC alleged that Jensen and Tekulve improperly included revenue from six sham transactions in Basin Water’s SEC filings. After a nine-day bench trial, Judge Manuel L. Real of the United States District Court for the Central District of California found the defendants not liable on each claim, stating “[n]o documentary evidence or witness testimony presented at the trial tended to show that any of the transactions were shams,” and that “there were valid economic justifications for all six of the transactions.”

And the trial losses have continued in early 2014. On January 7, after a two-day bench trial, Judge William Duffey, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia rejected the SEC’s claims against Ladislav “Larry” Schvacho, finding him not liable for insider trading. Allegedly, Schvacho traded stock based on material nonpublic information about Comsys IT Partners Inc. (“Comsys”), which the SEC claimed was provided to him by Comsys’ CEO, Larry L. Enterline, a close friend and business associate of Schvacho. At trial, the SEC relied on circumstantial evidence of communications and meetings between Schvacho and Enterline, but Judge Duffey found such reliance undermined by Enterline’s “unqualified testimony” that he did not give Schvacho inside information. The court found Enterline to be a credible and truthful witness and emphasized that, despite having brought the case to trial, the SEC did not even attack Enterline’s testimony or credibility.

While it is dangerous to draw broad conclusions from the small number of trials handled by the Enforcement Division every year, of which these are just a sample, this track record could certainly embolden defendants considering trial instead of settlement. The SEC’s recent trial losses have come in both federal court and administrative proceedings, in bench trials and jury trials, and in complex financial trials and straight-forward insider trading trials. In short, defendants have won in a wide range of cases, giving the defense bar cause to feel optimistic in resisting SEC charges in the future.

What is far less clear is whether the SEC’s mixed trial record will cause the Enforcement Division to rethink how it decides which cases to settle and which ones to take to trial. In light of the aggressive policy statements by Chair White and certain of her staff, it does not appear that the SEC is about to back down or bring fewer cases to trial. But if trial losses continue, changes may not be far behind. Whether that would mean being more selective about the cases the SEC chooses to bring, bringing cases to trial faster, or implementing more structural changes about the way the SEC investigates or litigates cases remains to be seen.

One statistic we will be watching in the coming year is whether the SEC will decide to bring more cases administratively rather than in federal court. The argument for bringing more cases administratively, in the post-Dodd-Frank era, is that the SEC may have more success administratively than in federal court because it is in a friendly forum where the procedural and evidentiary strictures either do not apply or are applied more liberally.

Significant New Initiatives and Developments

A. Change in “Neither Admit nor Deny” Policy

In June 2013, Chair White announced a change to the SEC’s longstanding policy of settling cases without requiring that defendants admit the charges against them. Chair White stated that, while the SEC would continue to permit defendants to settle without admitting allegations in most run-of-the-mill cases, it will now seek admissions of liability or, in the alternative, proceed to trial, in cases where the SEC concludes that public accountability is particularly important. Soon after these remarks, an internal memorandum to the SEC’s enforcement staff reportedly set forth three instances in which the Commission will seek an admission of liability. First, the Commission will seek admission of liability where the misconduct harmed large numbers of investors or placed investors or the market at risk of potentially serious harm. Second, the Commission will seek admission of liability where the allegedly violative conduct was egregious and intentional. Third, the Commission will seek admission of liability where the defendant engaged in an unlawful obstruction of the commission’s investigative processes.

This announcement followed highly publicized criticisms of the SEC’s “neither admit nor deny” policy, led by Judge Jed S. Rakoff of the Southern District of New York. In November 2011, Judge Rakoff refused to approve the SEC’s proposed $285 million settlement of a civil injunctive action the SEC brought against Citigroup Global Markets Inc. (“Citigroup”), concluding that he could not evaluate whether the settlement was in the public interest without knowing whether the SEC’s factual allegations were true. Soon after, other federal judges began to echo these concerns in evaluating SEC settlements. The SEC appealed Judge Rakoff’s rejection of its Citigroup settlement to the Second Circuit, and a decision—which could have major ramifications on SEC policy—could come down as soon as this month. If Judge Rakoff’s decision is upheld, it could force the SEC to make still more sweeping changes to its “neither admit nor deny” policy. But in the meantime, the SEC is working through how to apply its current policy and compel admissions in select cases.

In 2013, the SEC announced two settlements in which the defendants admitted wrongdoing, and, in both instances, the defendants agreed to lengthy statements of fact detailing their conduct. First, on August 19, 2013, the SEC announced a settlement in its pending civil injunctive action against hedge fund adviser Philip A. Falcone and his firm Harbinger Capital Partners (“Harbinger”). As part of the settlement, Falcone admitted that he had improperly borrowed $113.2 million from a Harbinger fund to pay his personal tax obligation when other fund investors were barred from making redemptions and that he had not disclosed the loan to investors for approximately five months. Falcone also admitted, as did Harbinger, that the fund had participated in an illegal “short squeeze,” interfering with the normal functioning of the securities markets. Falcone and Harbinger agreed to pay a total of $18 million in civil penalties, disgorgement, and pre-judgment interest. In addition, Falcone consented to a five-year bar from association with any broker, dealer, investment adviser, municipal securities dealer, municipal advisor, transfer agent, or nationally recognized statistical rating organization.

Second, on September 19, 2013, the SEC announced settled administrative proceedings against JPMorgan Chase & Co. (“JPMorgan”) related to the “London Whale” incident, in which JPMorgan suffered unexpected losses in one of the firm’s trading portfolios. The SEC alleged that JPMorgan had violated Sections 13(a), 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Exchange Act and Exchange Act Rules 13a-11, 13a-13, and 13a-15 when it disclosed the trading losses for the first quarter of 2012 and did not identify a material weakness in its internal controls. In August 2012, JPMorgan restated its financial statements for the first quarter of 2012 to include greater trading losses after concluding that it had a material weakness in its disclosure controls and procedures as of March 31, 2012. As part of the SEC settlement, JPMorgan admitted a 15-page statement of facts describing the events surrounding these disclosures. JPMorgan also agreed to pay a $200 million penalty to the SEC. This civil penalty was coupled with penalties paid to the UK Financial Conduct Authority, the Federal Reserve, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, totaling $920 million.

The SEC did not provide any clear guidance as to why it chose to demand admissions in these two cases, but not the many other cases in which it entered settlements during the second half of 2013. And particularly given that these two cases each involved somewhat idiosyncratic fact patterns, they certainly do not provide a large enough sample set to draw clear conclusions about the kinds of cases where the SEC will demand admissions in the future. One common aspect in both cases is that they were high-profile; but beyond that, it is difficult to identify meaningful similarities.

As the SEC enters more settlements with admissions in 2014, we expect clearer patterns to emerge as to when the SEC will insist on defendants admitting liability and to what types of conduct defendants will be compelled to admit. We also will learn more about the collateral consequences that such admissions will have on related civil litigation and insurance coverage. Meanwhile, we await the Second Circuit’s decision in the Citigroup case to see whether it may prompt further shifts in the policy.

B. Renewed Focus on Accounting Fraud

In FY2013, the SEC brought 68 enforcement actions that it identified as falling into the financial fraud or issuer disclosure category. This was the lowest number of financial fraud or issuer disclosure cases in over a decade, and marked the sixth straight year of declining numbers since a peak in 2007, when 219 financial fraud and issuer disclosure cases were filed. Perhaps consequently, in July 2013, the Enforcement Division announced three major new initiatives designed to bring financial fraud and issuer disclosure cases back to the forefront:

- The Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force – focuses on detecting fraudulent or improper financial reporting, including accounting fraud;

- The Microcap Fraud Task Force – targets abusive trading and fraudulent conduct in securities issued by microcap companies, especially those that do not regularly publicly report their financial results; and

- The Center for Risk and Quantitative Analytics – employs quantitative data and analysis to profile high-risk behaviors and transactions, supporting the Enforcement Division’s investigations and proactively trying to identify potential fraud.

According to Ceresney, the Enforcement Division implemented these changes because, while it has devoted fewer resources to focusing on accounting fraud since the financial crisis, it does not believe the problems of accounting fraud have disappeared. To the contrary, Ceresney has publicly doubted whether in fact there has been an actual drop in fraud in financial reporting as may be indicated by the numbers of investigations and cases filed by the Commission. Ceresney indicated that he believes that the incentives are still there to manipulate financial statements, and the methods for doing so are still available. Also, Ceresney indicated that he believes that the additional controls that have been instituted over the years to deter financial fraud are not always effective at finding fraud. We question Ceresney’s suggestion that the myriad internal controls that have been added since the days of Enron and Worldcom are not the reason (or at least a significant reason) that accounting fraud cases have declined in recent years. But it is clear that the SEC is not yet convinced. The SEC has not announced precisely how many individuals are assigned to each of these task forces; nor have we yet seen the fruits of this reprioritization. As we see more companies announcing SEC accounting fraud investigations throughout 2014, we expect that more evident trends and patterns will emerge.

C. The Office of the Whistleblower

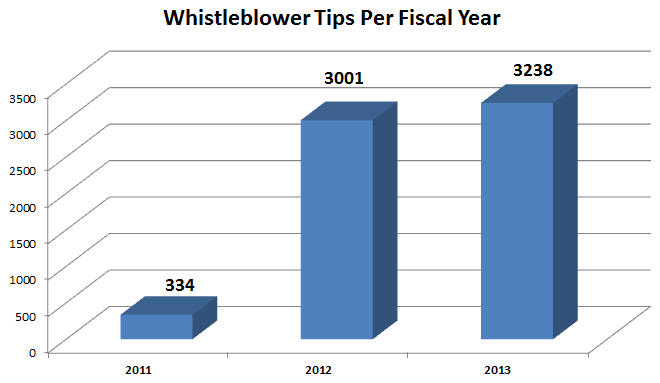

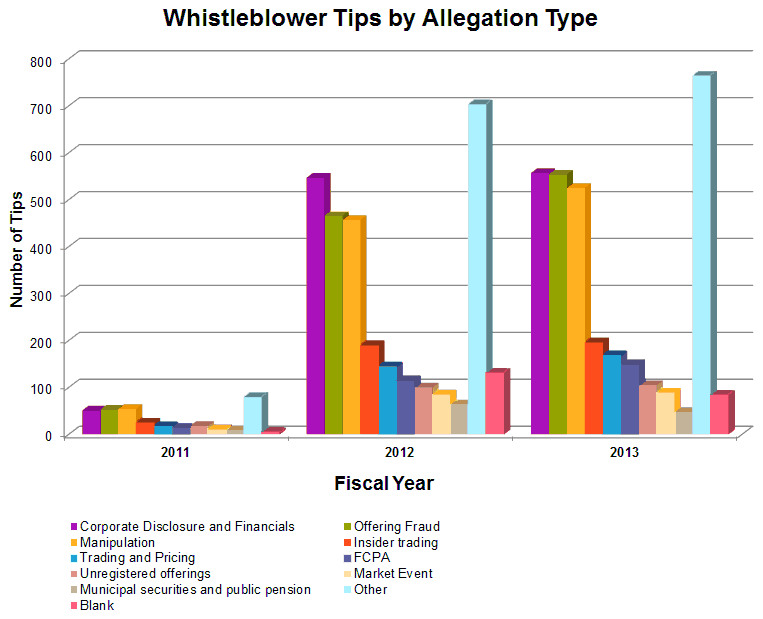

Between the establishment of the Dodd-Frank whistleblower program in August 2011 and the end of FY2013, the SEC received 6,573 tips and complaints from whistleblowers according to a report issued by the SEC. As the charts below demonstrate, the number of whistleblower tips received by the SEC grew slightly between FY2012 and FY2013, while the subject matter of the tips maintained a consistent spread over the SEC’s subject matter categories.

Sources: SEC Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, Fiscal Year 2011; SEC Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, Fiscal Year 2013. Note that low numbers for FY2011 reflect the fact that the whistleblower program was first implemented near the end of 2011.

While the number of tips received did not materially change in 2013, the awards did. The table below shows the dramatic increase in money awarded to whistleblowers in FY2013.

Whistleblower Awards by Fiscal Year

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Total Number of Awards | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Total Amount of Awards | $0 | $45,739 | $14,831,966 |

The four awards handed out in FY2013 were associated with two separate enforcement actions. On June 12, 2013, the Commission approved awards to three whistleblowers (but denied an award to a fourth claimant) who helped the Commission shut down Locust Offshore Management LLC, a hedge fund that had allegedly defrauded investors of $2.7 million. According to the SEC, two of the whistleblowers provided information that prompted the SEC to open its investigation of Locust and its CEO, Andrey Hicks, while the third whistleblower provided independent corroborating information and identified key witnesses. Each was awarded a percentage of the monetary sanctions to be collected in the SEC’s actions and an additional percentage of any criminal proceeds recovered. While the final amount of the awards will not be known for some time, it is expected to total over $125,000.

On October 1, 2013, the Commission awarded over $14 million to a single whistleblower, by far the largest award in the short history of the whistleblower program. According to the SEC, this whistleblower’s information led to a Commission enforcement action that recovered investor funds within six months of receiving the tip. As with other whistleblowers who have received awards to date, the whistleblower elected to remain anonymous. Then, on October 30, 2013, after the end of FY2013, the Commission awarded $150,000 to yet another anonymous whistleblower, which represented 30 percent of the amount collected in its action.

These awards represent an important success for the SEC. But what remains less clear is how many of the tips received by the SEC are generating successful investigations. It takes considerable resources to process and investigate the thousands of whistleblower tips now being received every year, and, without more information as to the quality of those tips, it is difficult to evaluate whether the SEC’s resources are being well spent. As more cases based on whistleblower tips are filed in the years to come, the degree of the program’s success should become more apparent.

D. The SEC’s First DPA with an Individual

Since then-Director Khuzami announced in January 2010 that the SEC was “expanding the [Enforcement] Division’s investigative toolbox to include cooperation agreements and related initiatives,” we have been watching for evidence of how the Division would use this expanded range of tools. While the SEC had announced cooperation agreements with corporations and individuals, and deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreement with corporations, until last year it had never entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with an individual.

On November 12, 2013, the SEC announced a deferred prosecution agreement with Scott Herckis, a former hedge fund administrator who helped the SEC take action against Berton M. Hochfeld, manager of the Connecticut-based Heppelwhite Fund LP (“Heppelwhite”), for stealing investor assets. Herckis had served as Hepplewhite’s administrator from December 2010 to September 2012, when, according to the SEC, he resigned, contacted government authorities to alert them to Hochfeld’s conduct, and began cooperating with investigations by the SEC and Department of Justice (“DOJ”). This cooperation reportedly allowed the SEC to file an emergency action against Hochfeld, freezing his assets for distribution to victims, and allowed the DOJ to bring parallel criminal charges against Hochfeld.

As part of the deferred prosecution agreement, Herckis admitted that, despite the fact that he eventually reported Hochfeld to the SEC, Herckis himself had aided and abetted Hochfeld’s fraud by improperly transferring Heppelwhite assets and preparing and providing materially overstated account statements to Heppelwhite’s auditors. Under the terms of the agreement, the SEC agreed not to bring charges against Herckis so long as he accepted responsibility for his conduct, continued to cooperate with the SEC’s investigation for a period of five years, paid approximately $50,000 in disgorgement and prejudgment interest, did not associate with any broker, dealer, investment adviser, or registered investment company, and complied with certain other undertakings.

It is unclear precisely why the SEC offered Herckis a deferred prosecution agreement, whereas it had offered other individuals cooperation agreements that included the filing of enforcement actions.

E. Supreme Court Update

In recent years, the Supreme Court has ruled on a number of important cases affecting the federal securities laws. See, e.g., Janus Capital Grp. v. First Derivative Traders, 131 S. Ct. 2296 (2011); Morrison v. Nat’l Austl. Bank Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010). Last year was no different. On February 27, 2013, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Gabelli v. SEC, 133 S. Ct. 1216 (2013).

In Gabelli, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected the SEC’s view that, under the catchall statute of limitations provision in 28 U.S.C. § 2462, government agencies can bring enforcement actions seeking civil penalties for fraudulent conduct more than five years after the conduct had taken place. The SEC had argued that a “discovery rule” should apply to such actions, meaning that the five-year period should not begin until it discovered the fraud, rather than when the fraud allegedly took place. The Supreme Court disagreed, reasoning that although a discovery rule makes sense in the context of private victims suing for fraud, it makes little sense in the context of government agencies specifically charged with rooting out fraud. The Supreme Court left open the question of whether the SEC (or other government agencies) can still benefit from equitable tolling of statutes of limitations when a defendant engages in specific conduct to conceal the underlying fraud, but that does not diminish the decision’s significance. The newly clarified limitations period will provide greater predictability to defendants and will force the SEC to speed its investigations.

In 2013 the Supreme Court also granted certiorari in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. Petitioner Halliburton asked the Supreme Court to revisit a 25-year-old precedent recognizing a presumption of reliance by private class members on alleged misrepresentations under the “fraud-on-the-market” theory. The fraud-on-the-market theory holds that any public misrepresentation affects the price of publicly traded securities because that price necessarily reflects all available information. If the Supreme Court finds that private plaintiffs cannot use the fraud-on-the-market theory to establish reliance, Halliburton would have a dramatic impact on private securities litigation. The potential impact of such a holding on SEC enforcement actions is less clear, given that the SEC need not prove reliance in enforcement actions. But a broadly worded decision could certainly impact how courts evaluate other aspects of the federal securities laws, such as materiality or the proper amount for disgorgement; it could also prompt the SEC to revisit its own policies, including how it distributes disgorged proceeds to victims under the fair fund program. Oral argument is scheduled for March 2014.

Significant Investigations and Cases

In addition to managing these programmatic changes, the SEC commenced and resolved significant investigations and litigations in each of its principal areas of focus in 2013. We review some of those investigations and litigations below.

A. Financial Crisis Cases

The SEC is now reaching “the outer end of the credit-crisis cases.” By the SEC’s statistics, through the end of FY2013, the SEC had charged 169 entities and individuals with securities law violations relating to the financial crisis and collected over $1.64 billion in civil penalties (resulting in over $3 billion in total monetary relief including prejudgment interest and disgorgement).

The most widely reported case in this area was the SEC’s successful trial against Fabrice Tourre, discussed above. At the same time it was proceeding to trial against Tourre, the SEC was also concluding its long-running investigation of the hedge fund Magnetar Capital LLC (“Magnetar”) and the CDOs it sponsored. The SEC did not bring suit against Magnetar, but in December 2013, it announced settled administrative proceedings against Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated (“Merrill Lynch”) in connection with three CDOs Merrill Lynch had marketed. For two of the three CDOs, the SEC alleged that Merrill Lynch misled investors by implying that collateral for the CDOs was selected in an independent process, without disclosing that Magnetar had played a role. For the third CDO, the SEC alleged that Merrill Lynch violated books-and-records requirements by improperly delaying the recording of trades. Merrill Lynch did not admit or deny the SEC’s allegations, but agreed to pay $131.8 million in civil penalties, disgorgement, and prejudgment interest.

The SEC also continued to investigate valuation cases related to the financial crisis, much as the DOJ is doing with its recent actions brought under the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (“FIRREA”).

In August, the SEC filed a civil injunctive action against a major financial institution relating to an offering of residential mortgage-backed securities in 2008. The SEC alleged that the financial institution had failed to inform all but a few favored investors that about 70 percent of the mortgages backing the offering originated in the high-risk “wholesale” channel, which its then-CEO supposedly referred to as “toxic waste.” The SEC claimed that the financial institution selectively disclosed the percentage of wholesale channel loans to certain institutional investors, but not the broader investing public. The defendants have moved to dismiss the SEC’s complaint, but the case is sub judice.

In November, the SEC filed a settled civil injunctive action against RBS Securities Inc. (“RBS”) for allegedly misleading investors in a 2007 offering of residential mortgage-backed securities. Allegedly, RBS stated that the mortgage loans backing the offering were “generally in accordance with” the lender’s underwriting standards, though due diligence had in fact shown that nearly 30 percent of the mortgages did not meet the underwriting standards. RBS settled the allegations, without admitting or denying the charges, by agreeing to pay $80.3 million in disgorgement, $25.2 million in prejudgment interest, and a $48.2 million civil penalty, for a total of more than $150 million.

B. Insider Trading

Insider trading continues to be a major emphasis for the SEC and its Enforcement Division. The SEC brought 44 insider trading enforcement actions in FY2013, a slight reduction from the 58 filed a year earlier; but many of the cases it brought last year were particularly high-profile. While the media coverage was dominated by the SEC and DOJ investigation of hedge fund SAC Capital Advisors, L.P. (“SAC”) and its principal, Steven A. Cohen, that was hardly the only area of focus for the SEC.

1. Auditors as Defendants

In a relatively rare case of an auditor being caught leaking material nonpublic information, the SEC instituted a civil injunctive action in April against Scott London, a former partner at KPMG in charge of the firm’s Pacific Southwest audit practice. The SEC alleged that London tipped a friend, Bryan Shaw, with confidential information about five KPMG audit clients, allowing Shaw to make more than $1.2 million in illegal trading profits ahead of earnings or merger announcements. According to the SEC, Shaw gave London bags of cash, Rolex watches, and other gifts in exchange for the tips. The US Attorney for the Central District of California announced parallel criminal charges against London, to which London pleaded guilty in July. London then settled with the SEC in September, agreeing to pay monetary penalties that are yet to be determined and agreeing to be barred from practicing before the SEC. While such cases are rare, the SEC’s recent focus on pursuing gatekeepers suggests that the SEC may further scrutinize audit firms.

2. Insider Trading Before Mergers and Acquisitions

The SEC filed a number of actions alleging trading ahead of merger or acquisition announcements. For example, in September, the SEC brought suit in United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida against Tibor Klein, the owner of a New York-based advisory firm, and his close personal friend, Michael Schectman. The SEC alleged that Klein learned nonpublic information about the impending purchase of King Pharmaceuticals by Pfizer Inc. from an attorney for King Pharmaceuticals. Klein purportedly traded on the basis of this information for his personal account and the account of his clients, and also tipped Schectman, who engaged in his own illegal trading. The SEC claimed that Klein and Schectman made more than $300,000 and $100,000 in illegal profits from the trades, respectively. Without admitting or denying the allegations, Schectman settled the charges earlier this month by agreeing to a permanent injunction and to pay disgorgement, pre-judgment interest, and a civil penalty in amounts to be determined by the court. Klein is litigating the charges.

Additionally, in June 2013, the SEC brought a civil injunctive action against and froze the assets of a Thailand-based trader, Badin Rungruangnavarat, who allegedly traded on inside information in advance of the announced acquisition of Smithfield Foods by China-based Shuanghui International Holdings. Rungruangnavarat allegedly made over $3 million in illegal profits by trading call options and single-stock futures contracts in the two weeks before the announced deal. Three months later, Rungruangnavarat agreed to settle the SEC’s suit, without admitting or denying liability, by paying $3.2 million in disgorgement and a $2 million civil penalty. This was one of a number of emergency actions filed by the SEC in 2013 to seize the assets of foreign-based traders after suspicious trading.

And one of the most striking SEC insider trading actions in the acquisition context came in April 2013, when the SEC brought a civil injunctive action against former investment banker Richard Bruce Moore for having purchased American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) of Tomkins plc, a United Kingdom company, ahead of an announcement that Tomkins had been approached with a takeover offer by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) and a Canadian private equity firm. The SEC alleged that Moore purchased the ADRs after learning that a friend/client, who was a CPPIB managing director, was working on a potential acquisition and then deducing that the acquisition target was Tomkins upon seeing the friend/client speaking with Tomkins’ CEO at a charity event. Even though Moore had not been told the acquisition target, the SEC claimed that Moore’s trades were unlawful because he had misappropriated material non-public information. The SEC’s aggressive view of what constituted material non-public information was not tested because, without admitting or denying liability, Moore agreed to settle the SEC’s charges by paying a civil penalty of $163,293 and disgorgement in the amount of $163,293 plus pre-judgment interest, for a total of $341,491.

3. Insider Trading Based on Family Relationships

Inside information shared among family members also continued to provide the SEC with a steady stream of insider trading cases in 2013. For example, in February, the SEC filed a settled civil injunctive action against James Balchan, who acquired shares of National Semiconductor Corp. after his wife, a partner at a large law firm, informed him that a social event for National Semiconductor’s general counsel had been canceled because the general counsel was busy working on an imminent merger. Balchan allegedly made $29,052 in profits by trading based on the inside information. He settled the SEC’s charges, without admitting or denying liability, by agreeing to pay disgorgement and prejudgment interest of $30,615, and an additional penalty equal to his profits of $29,052.

And in the continued fallout from the Galleon Group hedge fund insider trading investigation, in March, the SEC brought a civil injunctive action against Rengan Rajaratnam, the brother of Galleon’s Raj Rajaratnam, for trading on inside information provided by Raj. The SEC alleged that Rengan profited to the tune of over $3 million from his alleged illegal trading. The SEC sued Rengan Rajaratnam in the United Stated District Court for the Southern District of New York, where the case is currently stayed pending the outcome of parallel criminal charges.

4. SAC Capital Advisors, L.P.

As noted above, the media’s attention in 2013 was dominated by the long-running insider trading investigation of SAC, conducted in parallel with the criminal investigation by the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (the “SDNY”). The SDNY scored several victories against SAC and its employees in 2013. SAC itself pled guilty to criminal insider trading in November 2013, agreeing to pay $1.8 billion in forfeiture and criminal fines. Michael Steinberg, a former SAC portfolio manager against whom the SEC brought a parallel civil injunctive action, was convicted at trial of insider trading in December 2013. And the criminal case against Matthew Martoma, a former SAC portfolio manager against whom the SEC filed a parallel civil injunctive action for insider trading, got underway earlier this month.

Meanwhile, in July 2013, the SEC brought an administrative proceeding against Steven A. Cohen for failing to supervise SAC’s portfolio managers and prevent insider trading. Unlike the criminal actions filed to date, this action alleges wrongdoing by Cohen personally, and could result in an order barring him from the securities industry. The case is scheduled for trial before an administrative law judge in the spring.

C. Market Structure and Exchanges

The SEC brought two major cases against stock exchanges in 2013. While each of these actions was somewhat unique, they serve as reminders that the Enforcement Division is focused on market structure issues. Where it suspects unfair markets, the SEC is willing to devote substantial investigative resources in an effort to address structural deficiencies. These cases against the NASDAQ and the Chicago Board Options Exchange (“CBOE”) are discussed below.

First, in May, the SEC filed settled administrative proceedings against NASDAQ in connection with the botched Facebook initial public offering (“IPO”). According to the SEC’s complaint, there was a design flaw in NASDAQ’s computer system which delayed matches between buy and sell orders, and when NASDAQ initiated continuous trading on the morning of the Facebook IPO, over 30,000 orders for Facebook shares were supposedly “stuck” in NASDAQ’s computer system for over two hours when the orders should have been immediately executed or canceled. In addition, the SEC alleged that NASDAQ took a short position on more than three million Facebook shares in an unauthorized “error account.” Among other charges, the SEC alleged that NASDAQ had thus violated Section 19(g)(1) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”) by not complying with its order execution rules and the use of error accounts. NASDAQ settled the SEC’s allegations by agreeing to pay a $10 million civil penalty and to take remedial steps to prevent future violations.

Second, in June, the SEC instituted settled administrative proceedings against the CBOE and an affiliate for a variety of allegedly “systemic breakdowns” in the CBOE’s regulatory and compliance functions. This action grew primarily out of the SEC’s earlier litigated action against optionsXpress, an online brokerage and clearing firm (and CBOE member) that the SEC accused of systematically violating Regulation SHO, which governs short sale practices. The optionsXpress action resulted in a victory for the SEC at trial before an administrative law judge on June 7, 2013. The CBOE settlement was announced four days later. In the settled action, the SEC alleged that the CBOE had failed to meet its enforcement responsibilities as a self-regulatory organization between 2008 and 2012 by not effectively enforcing Regulation SHO or maintaining a sufficient surveillance program to detect abusive short selling. Moreover, the SEC alleged that the CBOE took “misguided and unprecedented steps” to assist optionsXpress when the SEC began its investigation of optionsXpress, including providing inaccurate and misleading information to optionsXpress for inclusion in a Wells submission to the SEC. The CBOE, without admitting or denying the SEC’s allegations, settled by agreeing to pay a $6 million penalty and agreeing to remedial undertakings designed to improve its regulatory program.

D. Broker-Dealers

The SEC continued its focus on broker-dealers, instituting 121 enforcement actions against broker-dealers in FY2013. The cases targeted a wide range of violations, but some of the most notable cases for broker-dealers were those focused on registration requirements, which the SEC continues to emphasize as a way to monitor the gatekeeping role that broker-dealers play in the securities market.

On March 11, the SEC initiated administrative proceedings against a New York-based asset management firm, Ranieri Partners LLC (“Ranieri”), and its former senior executive, Donald Phillips, for paying finders’ fees to William Stephens, a consultant solicitor who was not registered as a broker-dealer. The SEC alleged that Stephens violated Section 15(a) of the Exchange Act by acting as a broker, and not merely a finder, in soliciting more than $500 million in capital commitments for private funds managed by Ranieri. Further, the SEC alleged that Ranieri and Phillips caused and aided and abetted Stephens’ violations by failing to adequately supervise Stephens’ conduct. Without admitting or denying the charges, Ranieri, Phillips, and Stephens each agreed to settle. Ranieri paid a penalty of $375,000; Phillips paid a penalty of $75,000 and agreed to be suspended from acting in a supervisory capacity at an investment adviser or broker-dealer for nine months; and Stephens agreed to be permanently barred from the securities industry.

In another failure to register case, on June 5, 2013, the SEC filed a civil injunctive action against Banc de Binary Ltd. (“Banc de Binary”), a Cyprus-based company, that the SEC claimed was illegally selling binary option contracts to US investors without registering as a broker-dealer. In its press release announcing the litigation, the SEC emphasized the fact that Banc de Binary had solicited and obtained investments from many investors of extremely modest means. The district court granted the SEC’s motion for a preliminary injunction enjoining Banc de Binary from continuing to sell binary option contracts. This month, the SEC amended its complaint to add Oren Shabat Laurent, the President and CEO of Banc de Binary as a defendant. The litigation continues.

E. Investment Advisers and Investment Companies

In FY2013, the SEC brought 140 enforcement actions against investment advisers and investment companies. And, as was the case with broker-dealers, the types of cases against investment advisers covered a broad range. If any key themes can be drawn from the range of cases, they are that the SEC remains focused on improving compliance departments as a means of protecting investor assets and that no violation is too small to pursue.

In April, the SEC brought settled administrative proceedings against Vector Wealth Management, LLC, a Minnesota-based investment adviser. A clerical employee at Vector misappropriated over $33,000 in client dividends by writing checks to himself that a principal, apparently not paying close attention, then signed. The SEC found that the company had failed to adopt or implement procedures reasonably designed to identify violations of the asset custody rule in violation of Section 206(4) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 by failing to ensure that investors received quarterly account statements or audited annual financial statements. But because Vector itself discovered the violation, self-reported, and cooperated with the SEC’s investigation, the agency chose not to assess a monetary penalty.

In September, the SEC initiated administrative proceedings against 23 separate firms (including broker-dealers, as well as investment advisers and investment companies) for violations of Rule 105 of Regulation M. Of these 23 proceedings, 22 were filed as settled actions, while one is being litigated. Rule 105 of Regulation M generally prohibits a firm from selling short an equity security during the five days prior to a public offering if that firm then purchases the same security through the offering. The rule applies regardless of whether a firm intends to manipulate a stock’s price or otherwise engage in any deceptive device. The SEC touted this set of proceedings as a “sweep” that reflected its new “broken windows” policy. The SEC did not allege that any of the 23 defendant firms had a manipulative intent; nor did it single any of these firms out as a particularly bad actor. But as Chair White explained in October:

- We obtained disgorgement from nearly two dozen firms ranging from $4,000 to more than $2.5 million—showing that no amount is too small to escape our attention, and that going after smaller infractions will not distract us from larger ones. Even the cases with modest disgorgement amounts still translated into some sizeable sanctions, as we obtained a minimum penalty of $65,000 for the smallest violations.

- In the process, we sent a message that we will not tolerate any violations—big or small—that threaten the integrity of the capital raising process. And we think that the message is being heard.

Whether or not the message is in fact being heard, the cases were a useful reminder that the SEC will aggressively bring any action, even non-scienter-based actions, whenever it believes there is a useful deterrent impact.

The SEC also continued to leverage its examinations of investment advisory firms into enforcement actions. In October, the SEC announced settled administrative proceedings against Modern Portfolio Management Inc. (“MPM”) and Equitas Capital Advisers LLC (“Equitas”) and their owners. The SEC alleged that, notwithstanding the fact that the firms had been warned by SEC examiners of compliance deficiencies, the firms “did little or nothing to address [the deficiencies] by the next examination.” These compliance failures allegedly resulted in MPM making misleading statements about assets under management on its website and marketing materials, and resulted in Equitas making similar misstatements and inadvertently over-billing and under-billing certain clients. Without admitting or denying the allegations, each firm and its owners settled by accepting censures and agreeing to hire compliance consultants and comply with other remedial undertakings. In addition, MPM and its owners agreed to pay a total of $175,000 in penalties while Equitas and its owners agreed to pay a total of $225,000 in penalties.

F. Municipal Securities

Although the Enforcement Division formed a Municipal Securities and Public Pensions Unit in 2010, 2013 was the unit’s most active year to date. The unit not only brought more cases than ever before, but also brought cases that tested new theories of liability.

In May, the SEC filed settled administrative proceedings against the City of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, alleging that the City of Harrisburg had made fraudulent misstatements and omissions in its budget report, financial statements, and a State of the City address. The SEC alleged that the financial information provided by the City of Harrisburg in these various disclosures illegally masked the City of Harrisburg’s deteriorating financial condition. The City of Harrisburg consented to a cease-and-desist order, without admitting or denying the allegations. Notwithstanding the lack of a monetary penalty, the case was a bold statement by the SEC in that, while municipalities had been sanctioned for issuing incomplete formal disclosure documents in the past, this was the first time the SEC sanctioned a city for a speech on broader topics.

In July, the SEC charged the City of Miami, Florida, and its former budget director, Michael Boudreaux, in a civil injunctive action, alleging that the defendants had made false and misleading statements and omissions about interfund transfers in the City of Miami’s bond offerings and annual reports. The SEC’s decision to sue was likely influenced, at least in part, by the fact that the City of Miami was already subject to a cease-and-desist order that was entered against it in 2003 based on similar conduct. The SEC is seeking injunctive relief as well as financial penalties, and the case is currently being litigated (a rarity among municipal issuer cases) in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida.

In November, the SEC filed a settled administrative proceeding against Washington State’s Greater Wenatchee Regional Events Center Public Facilities District, alleging that investors were misled in a bond offering that financed the construction of a regional events center and ice hockey arena. The municipal corporation agreed to pay a civil penalty of $20,000 to settle the SEC’s claims, marking the first time the SEC assessed a financial penalty against a municipal issuer. In a statement accompanying the SEC’s announcement, however, Andrew Ceresney was careful to note that “[f]inancial penalties against municipal issuers are appropriate for sanctioning and deterring misconduct when, as here, they can be paid from operating funds without directly impacting taxpayers,” presumably suggesting that the SEC will not seek monetary penalties that would be satisfied directly from local or state tax revenues.

These were not the only cases brought by the Municipal Securities and Public Pensions Unit in 2013, but they provide an indication of the unit’s aggressiveness. Apparently recognizing that public issuers have had their share of fiscal problems in recent years, the SEC has clearly stepped up its enforcement oversight in this area, and we have every reason to think that it will continue in 2014.

G. China-based Fraud Still a Focus

Last year, the SEC continued its review of potentially violative conduct amongst China-based issuers. The SEC brought far fewer cases in this area in 2013 than it did in 2011 and 2012, but the cases it did bring suggest that its efforts are far from done. Instead, having brought dozens of cases against Chinese issuers in the last several years, the SEC now appears to be turning its attention to the gatekeepers that may have assisted (or at least failed to prevent) these entities in their violation of the federal securities laws.

In November, pursuant to Rule 102(e) of the SEC’s Rules of Practice, the SEC brought settled administrative proceedings against New York-based audit firm Sherb & Co. LLP and four individual auditors: Steven J. Sherb, Christopher A. Valleau, Mark Mycio, and Steven N. Epstein. The SEC alleged that these auditors failed to meet standards of professional conduct in their audits of three separate China-based issuers later accused of fraud (China Sky One Medical, China Education Alliance Inc., and Wowjoint Holdings Ltd.). The SEC did not contend that the auditors were complicit in the underlying fraud at these companies, but instead alleged that the respondents had failed to properly plan and execute the audits or maintain audit work papers, ignoring clear red flags and failing to exercise due care and professional skepticism. Without admitting or denying liability, the firm and individual respondents agreed to be barred from practicing as accountants on behalf of any publicly traded company or other entities regulated by the SEC. Additionally, Sherb & Co. agreed to pay a $75,000 penalty.

The SEC also continued to pursue the Chinese affiliates of major accounting firms for failing to provide the SEC with copies of the firms’ audit work papers. According to former Enforcement Director Khuzami: “Only with access to work papers of foreign public accounting firms can the SEC test the quality of the underlying audits and protect investors from the dangers of accounting fraud. Firms that conduct audits knowing they cannot comply with laws requiring access to these work papers face serious sanctions.” The two major litigations in this area have been the SEC’s pending subpoena enforcement action in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia against Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA Ltd. (“DTTC”) for failing to produce its audit work papers for the audit of China-based issuer Longtop Financial Technologies Ltd. (“Longtop”) in response to an SEC subpoena, and the SEC’s administrative proceedings against BDO China Dahua Co. Ltd., DTTC, Ernst & Young Hua Ming LLP, KPMG Huazhen (Special General Partnership), and PricewaterhouseCoopers Zhong Tian CPAs Ltd. for failing to provide audit work papers directly to the SEC in response to administrative requests. Both of these cases saw major developments in the last year.

On July 10, 2013, the SEC alerted the court in its subpoena enforcement action that China Securities Regulatory Commission (“CSRC”) had agreed to produce DTTC’s audit work papers relating to the underlying SEC investigation of Longtop. Then, in a status report filed with the court on November 4, 2013, the SEC confirmed that it had received 20 boxes of documents and a flash drive from the CSRC, representing a production of at least 200,000 pages of audit work papers and other documents of DTTC-related to Longtop. While the SEC has not yet taken a position on how the production should impact its subpoena enforcement action, the receipt of such documents was a sign of substantial progress in the SEC’s negotiations with the CSRC.

This progress has not, however, deterred the Enforcement Division in its administrative proceedings against the Chinese affiliates of major accounting firms. Notwithstanding the fact that the CSRC has now reportedly turned over to the SEC audit work papers related to at least six separate investigations, on January 22, 2014, the assigned Administrative Law Judge (“ALJ”) issued an Initial Decision finding that the audit firms had willfully violated the securities laws and recommending that they be barred from practicing before the SEC for a period of six months. The ALJ concluded that, even though the audit firms claimed to be willing to produce their audit work papers to the SEC through the CSRC (and, indeed, some have now done so), the refusal to produce such documents directly to the SEC violated their obligations as registered audit firms and required severe sanction. If upheld on appeal by the Commission (and, ultimately, the D.C. Circuit), this decision would have major ramifications, as it would prevent these firms from issuing or contributing to audit reports for US issuers for at least six months. The decision also has the potential to dial back the significant progress the SEC had apparently been making in its negotiations with the CSRC over the production of audit work papers.

H. Auditor Independence: Rosenberg Rich Berman & Co.

Also highlighting the Enforcement Division’s focus on gatekeepers, the SEC continued to police auditor independence issues. In one of its most significant 2013 such actions, the SEC brought settled administrative proceedings against Rosenberg Rich Berman & Co. (“Rosenberg Rich”), a New Jersey-based accounting firm, and one its partners, Brian Zucker. Allegedly, Zucker provided Financial and Operations Principal (“FINOP”) services for an unnamed broker-dealer client while Rosenberg Rich served as that broker dealer’s auditor. The SEC claimed that this not only constituted improper professional conduct and a violation of the auditor independence rules, but also caused the broker-dealer to fail to file an annual report audited by an independent accountant (because Rosenberg Rich filed the audited report). Without admitting or denying the allegations, Zucker agreed to be suspended from practicing before the SEC for at least one year (at which point he can apply for reinstatement) and Rosenberg Rich agreed to pay $12,000 in disgorgement and a $25,000 penalty.

I. Clarifying Regulation Fair Disclosure

The Enforcement Division addressed lingering questions about Regulation FD’s application to social media outlets like Facebook and Twitter. Regulation FD is designed to prevent selective disclosure, and requires issuers to disclose material nonpublic information to the public whenever that information is disclosed to holders of the issuer’s securities or securities market professionals. In April 2013, the SEC announced its view that Regulation FD applies to social media and “other emerging means of communication” the same way it applies to company websites: social media may be used to announce material information, but only if investors have been alerted beforehand as to which social media will be used to disseminate such information.

The genesis of the SEC’s announcement was a July 2012 Facebook post by Netflix CEO Reed Hastings. Hastings announced on his personal Facebook page that Netflix had streamed one billion hours of content in the prior month, but Netflix did not concurrently announce that information in a press release, on its website, or in a Form 8-K. The SEC launched an investigation into Hastings’ disclosure and concluded that uncertainty existed as to the applicability of Regulation FD to disclosures made via social media. Accordingly, instead of bringing an enforcement action, the SEC issued a report under Section 21(a) of the Exchange Act. In its Section 21(a) Report, the SEC noted that while it would not pursue an enforcement action against Hastings or Netflix, disclosure of material information without notice on the personal social media page of a corporate officer in the future would be unlikely to meet Regulation FD’s requirements.

J. FCPA

Last year, in our firm’s annual FCPA Digest, we noted that 2012 had been “a fairly slow time” in terms of corporate enforcement actions, with 12 enforcement actions against corporations. 2013 was slower still, with only nine corporate enforcement actions between the DOJ and SEC combined. There was a steep increase in corporate fines, however, and enforcement against individuals also saw a marked increase, from five in 2012 to 16 in 2013—eight of whom pleaded guilty. Among the highlights:

- Over $720 million in penalties in 2013, and the average penalties ($80 million) and the adjusted average ($28 million) were both considerably up from previous years;

- Significant number of new cases against individuals;

- Surge in “hybrid” monitors, with an independent monitor’s term of 18 months followed by 18 months of self-monitoring;

- Continued aggressive theories of jurisdiction and parent-subsidiary liability; and

- Adoption of deferred prosecution agreements in the UK, albeit with substantially more judicial involvement than in the US

In 2013, the government brought nine enforcement actions against corporations: (i) Philips, (ii) Parker Drilling, (iii) Ralph Lauren, (iv) Total, (v) Diebold, (vi) Stryker, (vii) Weatherford, (viii) Bilfinger, and (ix) Archer Daniels Midland (ADM).

This is the lowest number in the past seven years, which had seen annual totals averaging 13 cases per year since 2007. Most of these cases were coordinated actions brought by both the SEC and the DOJ, with only two independent actions brought by the SEC (Philips and Stryker) and one from the DOJ (Bilfinger). It is difficult to say whether the lower rate of corporate enforcement is a trend, in spite of the relatively low 12 corporate enforcement actions in the prior year. Although a substantial number of companies have announced new investigations or reserves for enforcement fines in recent years, there have only been a handful of publicly announced declinations. The regulators, for their part, have swept aside any suggestions of waning enforcement, stating that both the DOJ and the SEC have a substantial pipeline of FCPA cases awaiting announcement.

Unlike the lower number of corporate matters, the year saw a surge in individual actions, with 12 charged in 2013. In addition, four individual actions brought in 2012 were unsealed in 2013 (thus we have included them in our statistics for 2013). Only five of these individual actions were connected with previous enforcement actions: Jald Jensen, Bernd Kowalewski, Neal Uhl, and Peter Dubois (incidentally, the group of individuals whose filings were belatedly unsealed in 2013) were all affiliated with Bizjet, which settled with the DOJ in 2012; and Alain Riedo was a Swiss-national executive at Maxwell Technologies, which settled with the DOJ and SEC in 2012. The remaining 11 fell into two group actions, and one rather unique freestanding action: Lawrence Hoskins, Frederic Pierucci, William Pomponi, and David Rothschild were employed by and allegedly participated in a scheme at French company Alstom SA (which has not yet been subject to an enforcement action), while Iuri Rodolfo Bethancourt, Tomas Alberto Bethancourt Clarke, Jose Alejandro Hurtado, Haydee Leticia Pabon, Maria de los Angeles de Hernandez Gonzalez, and Ernesto Lujan allegedly participated in a scheme involving a New York broker-dealer called Direct Access Partners, LLC. Among the broker-dealer defendants, Gonzalez was a Venezuelan government official charged not with FCPA bribery but with money laundering and Travel Act violations for accepting bribes. The final individual action was an obstruction of justice case against Frederic Cilins, a French national who allegedly interfered in a government investigation of a mining company’s potential violations of the FCPA in Guinea. Press reports indicate that the mining company is Beny Steinmetz Group Resources (BSGR), which has denied any wrongdoing but is under investigation in several countries, including Switzerland.

On the penalties side, the corporate penalties assessed in 2013 were markedly higher than in 2012 and rebounded to levels last seen in 2010. Altogether, the government collected $720,668,902 in financial penalties (fines, DPA/NPA penalties, disgorgement, and pre-judgment interest) from corporations in 2013. This equates to an average of $80 million per corporation, with an exceptionally large range of $1.6 million (Ralph Lauren) to $152.79 million (Weatherford) and $398.2 million (Total). Weatherford and Total’s penalties are, each respectively, over three times that of any of the other companies. Weatherford’s high fines appear to stem from the company’s widespread bribery schemes and particularly “anemic” compliance systems and controls, as well as its initial failure to cooperate with the authorities. Total engaged in a bribery scheme that spanned a decade and resulted in over $150 million in profits, resulting in the second highest disgorgement in FCPA enforcement history. Meanwhile, Ralph Lauren’s low fines were purportedly the result of the “exceptional” self-reporting, cooperation, and remediation that led to an unprecedented double-NPA, although the isolated nature of the bribes (and resulting low disgorgement) likely factored in as well. When we remove those three outliers, the average is $28 million. This is in line with the averages calculated in recent years using the same criteria ($17.7 million in 2012 and $22.1 million in 2011).

On the individuals side, Riedo is a fugitive and two others, Cilins and Alstom executive Pomponi, are each pending trial. Two of the Alstom defendants, Rothschild and Pierucci, have pleaded guilty, while the status of the fourth Alstom defendant Hoskins is yet unclear. Similarly among the Bizjet defendants, the status is unclear for two defendants (Jensen and Kowalewski) while two pleaded guilty (Uhl and DuBois). Uhl and Dubois were each sentenced to 60 months’ probation and eight months’ home detention, with a $10,100 fine imposed on Uhl and a $159,950 fine imposed on DuBois. Finally, all four of the broker-dealer defendants in the DOJ proceedings (Clarke Bethancourt, Hurtado, Gonzalez, and Lujan) have pleaded guilty, with sentencing scheduled for 2014. The parallel civil proceedings (with additional defendants Bethancourt and Pabon) were stayed pending resolution of the criminal case, and the stay had not been lifted as of December 2013.

In addition to the relative profusion of new individual enforcement, there were sentencings and other case developments in numerous pending actions. After a slew of guilty pleas last year, three CCI defendants were sentenced: Flavio Ricotti to time served and Mario Covino and Richard Morlok to three years’ probation and three years’ home confinement. The CCI cases are thus fully resolved, save for Korean national Han Yong Kim, whose request to make a “special appearance” was denied in June.

Meanwhile, in the case against the Siemens executives, the DOJ’s cases appear to be stalled, with none of the defendants choosing to come to the US to answer charges and apparently no success thus far in obtaining extradition of them. On the other hand, the SEC civil enforcement action seems close to being resolved, albeit in some strange and uneven ways. Herbert Steffen’s motion to dismiss was granted for lack of jurisdiction, and the SEC voluntarily dismissed all claims against Carlos Sergi, while Uriel Sharef settled with the SEC for a $275,000 civil penalty—the second-highest penalty assessed against an individual in an FCPA case. The SEC indicated that it has reached an agreement-in-principle to settle claims against Andres Truppel, and has requested that the court enter default judgments against Stephan Signer and Ulrich Bock.

In contrast, the three Magyar Telekom executives charged by the SEC, Elek Straub, Andras Balogh, and Tamas Morvai, are apparently proceeding to trial and have now entered the pretrial discovery phase, after the defendants’ motions to dismiss were denied in February 2013. Similarly, the Noble executives James Ruehlen and Mark Jackson are also on their way to trial; after considerable pre-trial litigation regarding the statute of limitation and other issues resulting in the SEC filing an amended complaint in March 2013, Ruehlen and Jackson filed answers on April 2013, denying most of the SEC’s allegations.

In yet another case with multiple individual defendants, Haiti Telecom, the legal battles continue. Briefs were filed in the appeal of Jean Rene Duperval, while oral arguments were held in the appeal of Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez. Three of the remaining defendants (Washington Vasconez Cruz, Amadeus Richers, and Cecilia Zurita) have been classified as fugitives, and Marguerite Grandison’s case was closed when she entered into an 18-month diversion program.

Finally, the year also saw resolutions from the rather distant past, with Thomas Farrell, Clayton Lewis, and Hans Bodmer (all charged in 2003) each sentenced to time served, and Paul Novak (charged in 2008) sentenced to 15 months in prison and a $1 million fine. In addition, Frederic Bourke’s long legal journey (charged in 2005) finally came to an end. After two unsuccessful appeals of his original 2009 conviction, the United States Supreme Court refused to hear his case. He began his prison sentence of one year and one day in May 2013.

Conclusion

In 2013, like the rest of the Commission, the Enforcement Division was in transition, as a new Chair and new directors took charge. The new leadership brought shifts in priorities and programs. But given the long pipeline of investigations, and the many corners of the securities markets policed by the Enforcement Division, the true effects of any changes will be seen only in years to come. In the meantime, we expect that 2014 will bring much more of the same—aggressive enforcement in all areas, as the Division tries to address any “broken windows” it can identify.

Print

Print