The following post comes to us from David Min of University of California, Irvine School of Law.

Last week, James Kwak (UConn law professor, co-author of 13 Bankers and White House Burning, and blogger at the Baseline Scenario) provided a nice writeup of some of the key issues I identify in my paper, Understanding the Failures of Market Discipline, recently posted to SSRN. But I wanted to take a few words to provide a slightly more detailed explanation of my work.

“Market discipline”—the notion that short-term creditors (such as bank depositors) can efficiently identify and rein in bank risk—has been a central pillar of banking regulation since the 1980s. Obviously, market discipline did not prevent the buildup of bank risk that caused the recent financial crisis, but the general consensus has been that this failure was due to structural impediments to the effective operation of market discipline—such as misaligned incentives, a lack of transparency, or moral hazard caused by implicit guarantees—rather than any problems with the concept itself. As a result, a major point of emphasis in financial regulatory reform efforts has been to improve and strengthen market discipline.

I reject this conventional wisdom, and make two new contributions to the literature. First, I demonstrate that market discipline failed much more severely and completely than has previously been acknowledged, and that this failure was inconsistent with the explanations that are generally offered. Second, I attempt to explain the causes of this failure.

The theory of market discipline generally asserts that depositors and other short-term bank creditors can play an important role in reducing bank risk. Market discipline was supposed to work through two main effects. First, the reactions of interested investors—withdrawing funds and/or demanding higher rates of return from banks taking on greater levels of risk—were themselves supposed to act as a check on the behavior of bank managers, by providing a deterrent (less availability and a higher cost of funds) to taking on greater risk. Second, these market reactions (particularly changes in the prices of bank-issued liabilities) would also help to identify risky banks for regulators.

A foundational premise of both of these mechanisms was that market discipline would accurately and timely identify risky banks. Troublingly, and as yet unrecognized by policy makers, this did not happen in the period preceding the financial crisis. Every significant market indicator that should have signaled high levels of bank risk—uninsured deposit rates, bank subordinated debt rates, interbank lending rates, credit default swap prices, and many others—failed to provide any indication of high levels of risk until after the crisis had already started, at which point it was too late for regulators to react effectively. In other words, market discipline failed far more severely and completely than has generally been understood.

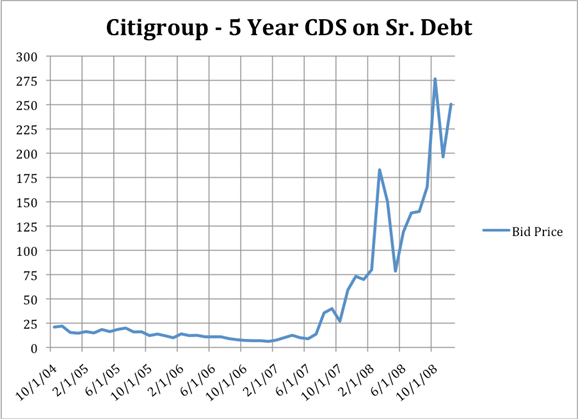

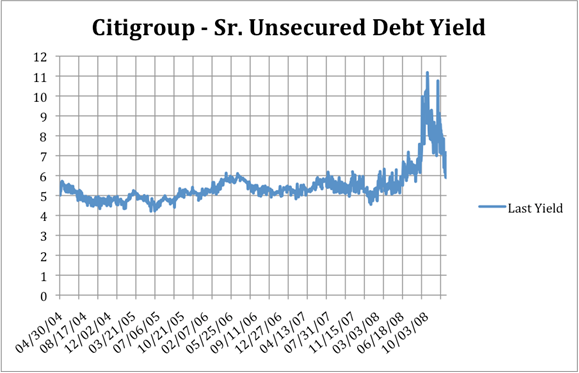

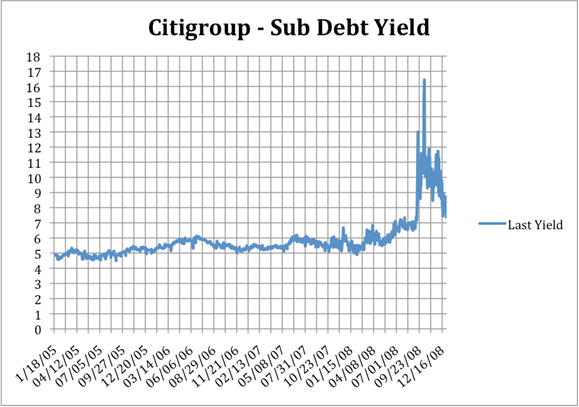

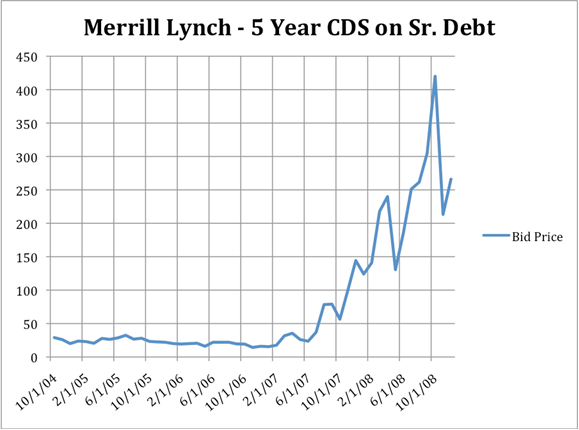

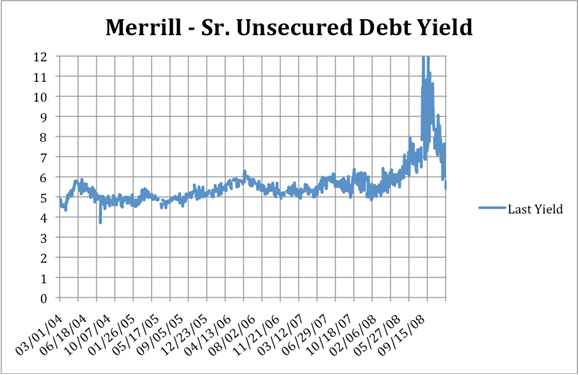

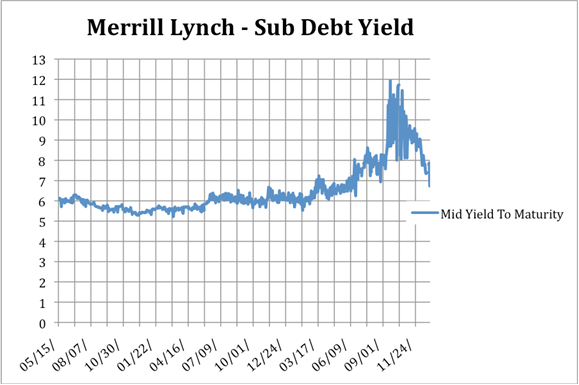

The below charts, taken from my paper, provide some illustration of this phenomenon. The first six charts look at the pricing of three types of supposedly risk-sensitive bank securities issued by Citigroup and Merrill Lynch (two firms that had taken on idiosyncratically high levels of subprime mortgage exposure). As the charts indicate, these pricing signals were almost completely inert until July 2007, at which point they became quite volatile. What happened in July 2007? Moody’s and S&P, two of the three major credit rating agencies, downgraded over 1,000 AAA-rated subprime securities.

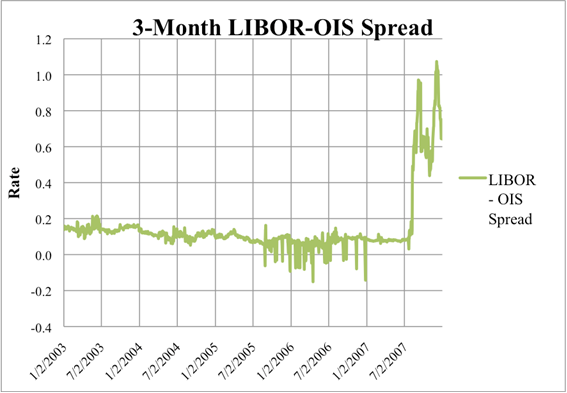

This problem was not confined to individual institutions, but also was seen in various systemic and interbank pricing signals. For example, as the below chart shows, the 3-month LIBOR-OIS spread, considered a leading measure of systemic bank risk because it represents the effective interest rate at which banks are willing to lend to one another, also did not signal rising risk until after July 2007.

Why did market discipline fail so badly? The standard account is that some predicate condition for the success of market discipline was lacking. A flurry of post-crisis papers have identified misaligned incentives, a lack of sufficiently detailed or clear information, and moral hazard as reasons why market discipline did not succeed in preventing bank risk-taking.

The problem with these explanations is that they do not well explain the actual experience of market discipline before and during the financial crisis—longstanding and complete investor complacency, followed by a sudden and violent spate of activity beginning in July 2007, just after the mass ratings downgrade. Even if we accept the argument that market discipline was impeded by poor conditions, we still should have seen some (albeit less than optimal) degree of market discipline, particularly given all the growing evidence of rising bank risk in 2006 and 2007. And we should not have seen a sudden increase in market discipline simply because the rating agencies downgraded some AAA-rated securities. The fact that market discipline was so completely inert up until the ratings downgrades of July 2007, and then so suddenly reactive, is strong evidence that the conventional explanations are wrong.

So what actually happened? I argue that market discipline conflates two very distinct types of bank-issued securities—those that are money instruments (such as bank deposits), and those that are ordinary investment securities (such as stocks and bonds). This confusion between money instruments and investment securities has led to two critical structural flaws with market discipline. First, market discipline relies primarily upon the market reactions of investors in money instruments, but these investors are relatively insensitive to risk, as money instruments are specifically designed to not fluctuate in value in response to new risk-related information. Second, market discipline generally ignores the monitoring and disciplining performed by shareholders, who are indeed quite sensitive to bank risk but often want to see greater risk-taking (since most of the downside risk is borne by bank creditors). Indeed, it is quite clear that much of the bank risk-taking we saw prior to the crisis was a direct response to shareholder pressure, as I document.

These findings lead to a number of fairly strong, and sometimes radical, policy recommendations. At a high level, I argue for significantly reduced reliance on market discipline, which means as a corollary that policy makers must improve and increase the traditional “old school” prudential buffers against bank failure (particularly capital requirements). Moreover, I conclude that the current trends towards increasing bank transparency and more closely aligning the interests of managers and shareholders should be reevaluated, as these may be antithetical to the interests of bank safety and soundness. Finally, my findings provide another arrow in the quiver for those seeking to reduce the size and complexity of financial institutions. Regulators have come to increasingly rely upon market discipline in regulating large and complex financial institutions, because they are increasingly incapable of understanding and identifying risk in these firms. If, as I conclude, market discipline is fundamentally flawed, then these institutions are not only “too big to fail,” but they are clearly “too big to regulate” as well.

The full article is available for download here.

Print

Print