The following post comes to us from Alexandria Carr, Of Counsel with the Financial Services Regulatory & Enforcement group at Mayer Brown LLP, and is based on a Mayer Brown Legal Update; the complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

1. On 10 April 2014 some of the legislation that provides for the extraterritorial effect of the European Markets Infrastructure Regulation (“EMIR”) came into force. The remaining legislation will come into force on 10 October 2014. This post considers this legislation and the counterparties to which it applies. It also considers whether some counterparties might be able to avoid the extraterritorial effect as a result of the European Commission making an equivalence decision in respect of third country jurisdictions. It considers the European Securities and Market Authority (“ESMA”) advice to date on the equivalence of the regulatory regimes in the US, Japan, Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Singapore, South Korea and Switzerland and notes that even in the US ESMA did not find full equivalence. Finally this post also considers the requirements that third country central counterparties (“CCPs”) and trade repositories must meet in order respectively to provide clearing services to their EU clearing members and to provide reporting services to EU counterparties which enable those counterparties to satisfy their clearing reporting requirements under EMIR.

2. There are real risks that the extraterritorial effect of the EU legislation, particularly when combined with the extraterritorial effects of third country legislation, will disrupt cross-border trades. There is an urgent need for regulators to agree, in particular, on how counterparties established in different jurisdictions are expected to comply with duplicative clearing obligations. This post, therefore, also considers the consequences of the application of EMIR to cross-border transactions.

3. We have sought to address all points that are relevant as regards non-EU counterparties. The index below will assist those readers who wish to focus only on specific areas:

The extraterritorial effect of EMIR

4. EMIR was considered in our legal update entitled “A Quick Start Guide to EMIR”. This post focuses on the extraterritorial reach of EMIR. EMIR explicitly states that it has extraterritorial effect in two situations:

- (a) The clearing obligation applies to contracts entered into by a “financial counterparty” or a “non-financial counterparty+” in the EU and a third country entity provided that the third country entity would be subject to the clearing obligation if it were established in the EU. Only non-EU entities that would be categorised as financial counterparties or qualifying non-financial counterparties were they established in the EU would be subject to the clearing obligation in these circumstances.

- (b) Both the clearing obligation and the risk mitigation requirements apply to contracts between third country entities that would be subject to the clearing obligation if they were established in the EU, provided that the contract has a “direct, substantial and foreseeable effect within the EU” or where such an obligation is necessary or appropriate to prevent the evasion of any provisions of EMIR. Again this provision only captures non-EU entities that would be categorised as financial counterparties or qualifying non-financial counterparties under EMIR.

In addition, market developments are creating an indirect extraterritorial effect as EU counterparties already bound to comply with the reporting obligation and the EMIR risk mitigation requirements that apply to uncleared trades are encouraging their non-EU counterparties to comply also so as to facilitate their own compliance.

5. These direct and indirect extraterritorial effects and their consequences are considered in detail at paragraphs 19-30 of the full publication (available here). The possibility of complying with third country regimes that have been declared equivalent to the EU regime as opposed to complying with EMIR is considered at paragraphs 31-65. Before considering the extraterritorial effects and the concept of equivalence further, however, it is necessary to summarise the general scope and application of EMIR so as to put into context the terms and concepts used in the EU legislation.

Scope of EMIR:

6. EMIR applies to any legal or natural person established in the EU that is a legal counterparty to a derivative contract, including interest rate, foreign exchange, equity, credit and commodity derivatives. EMIR identifies two main categories of counterparty to a derivatives contract:

- (a) “financial counterparties” (“FC”), which includes EU authorised financial institutions such as banks, insurers, MiFID investment firms, UCITS funds and, where appropriate, their management companies, occupational pension schemes and alternative investment funds managed by a manager authorised or registered under AIFMD; and

- (b) “non-financial counterparties” (“NFC”), which means an undertaking established in the EU which is not classified as a FC, including entities not involved in financial services.

7. The Commission has made clear in its FAQ on EMIR that the concept of “undertaking” in the definition of a NFC covers any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of the legal status of the entity or the way in which it is financed. Case law of the European Court of Justice is consistent with this approach and has made clear that any activity consisting in offering goods and services on a market is an economic activity. Accordingly, individuals and non-profit entities carrying out an economic activity are considered to be undertakings and thus capable of being NFCs, provided they offer goods and services in the market. The concept does not extend to include public authorities.

8. A NFC whose positions in OTC derivatives exceeds a clearing threshold is known as a “qualifying non-financial counterparty” (“NFC+”). In general, NFCs+ are treated in the same way as FCs. It is the responsibility of the NFC to determine whether or not its positions exceed the clearing threshold and to notify ESMA and the relevant national regulator if this is the case.

9. In essence, for the purpose of determining whether a NFC exceeds the thresholds so as to become a NFC+, hedging transactions are excluded from the calculation of positions in OTC derivative contracts. The calculation of positions must include all OTC derivative contracts entered into by the NFC itself or other NFCs within its group which are not objectively measurable as reducing risks directly related to the commercial activity or treasury financing activity of the counterparty or of its group. The thresholds differ according to the type of derivative contract and are determined by taking into account the systemic relevance of the sum of the net positions and exposures per counterparty and per class of OTC derivative. The thresholds, and the criteria for establishing which contracts can be deemed to be for hedging purposes, are set out in the subordinate legislation adopted by the Commission on 19 December 2012.

How does EMIR categorise non-EU counterparties?

10. Given the cross-reference to regulatory authorisation, it is straight-forward to establish whether an EU counterparty is a FC. It is also relatively easy to establish whether a non-EU counterparty is a FC as ESMA’s Q & A13 directs that consideration should be given to the nature of the activities the non-EU entity undertakes. It is less easy to establish whether any counterparty is a NFC+ and the appropriate categorisation of non-EU NFCs.

11. It is first worth considering when an entity is a non-EU entity. Entities without any physical presence in the EU are clearly non- EU entities but further consideration needs to be given to non-EU entities that have EU subsidiaries and branches. In its FAQ the Commission summarises that for the purpose of the application of EMIR, a NFC refers to an undertaking established in the EU but points out that “undertaking” and “established” are not further defined.

12. We have explained the concept of “undertaking” at paragraph 7 above but the concept of establishment is crucial to the treatment of branches and subsidiaries in the EU. This concept is an EU construct that is not set out in any one place in particular but is the subject of legal definition based on EU primary legislation dealing with the right of establishment (Articles 49–55 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU) and subsequent case law. The concept does not include branches: establishment refers to the establishment of solo entities with individual legal identity which are incorporated (or are domiciled or have their registered office) in a Member State in the EU. As a result, subsidiaries are included within the concept but branches are not capable of being established in their own right. Thus a subsidiary of a non-EU entity can be established in the EU but a branch cannot. To summarise, if bank A is a bank headquartered and regulated in the US and has a branch (“B”) in Dublin and a subsidiary (“S”) in London, A and B are non-EU entities but S is an EU entity.

13. We have already commented that it is relatively straight-forward to assess whether a non-EU entity would be regarded as an FC if it were established in the EU. In the example given in the above paragraph, as A is regulated as a bank in the US, it would be a non-EU FC. It is more difficult in the case of non-EU NFCs and NFCs+. ESMA’s Q&A provides that if the non-EU entity is part of a group which also includes NFCs established in the EU, its status as either an NFC+ or NFC should be assumed to be the same as that of the EU NFCs. If the non-EU entity is not part of such a group, but benefits from a similar but limited exemption in its own jurisdiction, it can be assumed that the entity would be NFC were it established in the EU.

14. If neither of the above applies, however, then there is only one way to determine conclusively whether a non-EU entity is a NFC or NFC+: it would have to calculate its group-level position against the EMIR clearing threshold.

15. EU counterparties should obtain representations from their non-EU counterparties detailing their status. The EU counterparty is not expected to conduct verifications of the representations and may rely on such representations unless they are in possession of information which clearly demonstrates that those representations are incorrect. If it is not possible to obtain such representations and assess what the counterparty’s status would be under EMIR, firms should assume that their counterparty status is NFC+ and apply the EMIR requirements accordingly.

16. Seemingly, when non-EU counterparties are themselves directly bound by EMIR, the onus is on them to establish their appropriate categorisation under EMIR.

Application of EMIR to different counterparties

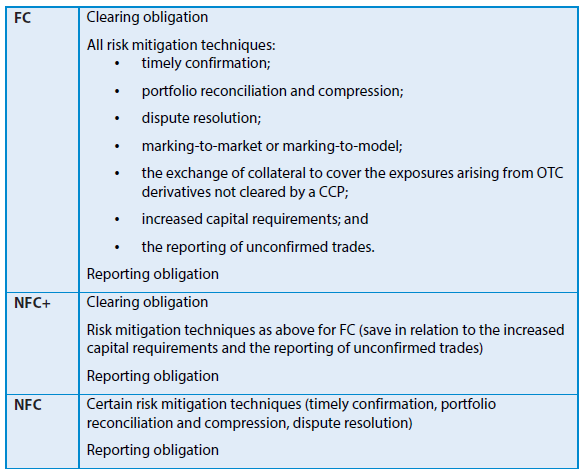

17. The provisions in EMIR apply differently to NFCs+ than to NFCs. In general, NFCs+ are treated in the same way as FCs. The provisions applicable to the different types of counterparty are as follows:

18. Non-EU counterparties are not, however, treated in the same way as their EU counterparties.

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print