The following post comes to us from Matt Orsagh, director at CFA Institute, and is based on the summary of a CFA publication, titled Proxy Access in the United States: Revisiting the Proposed SEC Rule; the complete publication is available here.

In this summary of CFA Institute findings, we take a brief look at the history of proxy access, discuss the pertinent academic studies, examine the benefits and limits of cost–benefit analysis, analyze the use of proxy access in non-US jurisdictions, and draw some conclusions.

How We Got Here

Proxy access refers to the ability of shareowners to place their nominees for director on a company’s proxy ballot. This right is available in many markets, though not in the United States. Supporters of proxy access argue that it increases the accountability of corporate boards by allowing shareowners to nominate a limited number of board directors. Afraid that special-interest groups could hijack the process, opponents of proxy access are also concerned about its cost and are not convinced that proxy access would improve either company or board performance.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) most recently attempted to give shareowners proxy access in 2010, when it passed a proxy access rule (Rule 14a-11) [1] pursuant to section 971 of the Dodd–Frank Act. A lawsuit challenging the rule succeeded when the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated the SEC’s proposed rule, holding that the SEC had failed to adequately assess the economic effects of the proposed rule. [2] The SEC did not appeal the court’s decision.

This post attempts to address the questions raised by the DC Circuit Court by analyzing event studies, other data, and examples of proxy access in non-US jurisdictions with respect to the costs and benefits of proxy access. Taken together, the event studies analyzed in this report examine whether proxy access, on the particular event date, would have been beneficial or harmful to market performance, stock performance, and board performance and whether the potential use of proxy access by special-interest groups would have reduced shareowner wealth.

Academic Studies

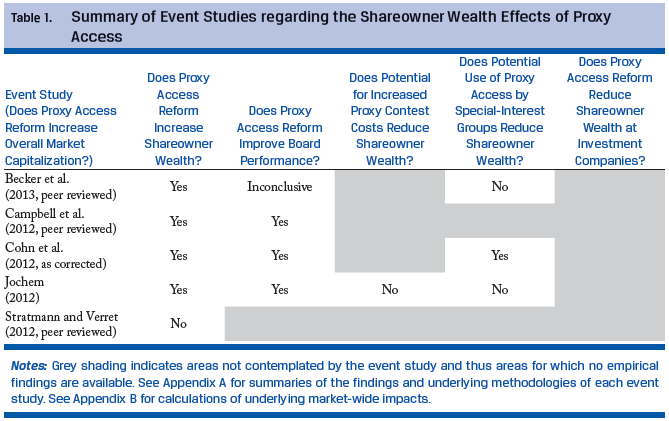

In conducting this research, CFA Institute retained the services of Industrial Economics, Incorporated (IEc), to assess the economic impacts associated with the SEC’s proposed proxy access rule. The remainder of this report, following this executive summary, comprises IEc’s analysis and discussion. Table 1 summarizes the results of the five event studies [3] reviewed by IEc in the context of five shortcomings of the SEC’s economic analysis of Rule 14a-11, as identified by the DC Circuit Court.

The event studies cited in Table 1 attempt to identify empirically whether proxy access benefits or harms shareowners. Using econometric methods, these studies estimate firm-level abnormal returns, defined as the deviation of the actual return from its expected value on an array of event dates. Each study focuses on an event window relevant to the availability of proxy access rights that the authors contend is economically significant and generally unexpected by the market. On the basis of their findings, the authors conclude whether proxy access creates or destroys shareowner wealth.

Three studies offer evidence that proxy access reform enhances board performance. Of the three studies that assess whether the use of proxy access by special-interest groups reduces shareowner wealth, two studies provide evidence that it does not. Finally, only one event study assesses the impact of increased proxy contest costs on shareowner wealth; the results of this study show evidence that increased proxy contest costs do not appear to reduce shareowner wealth.

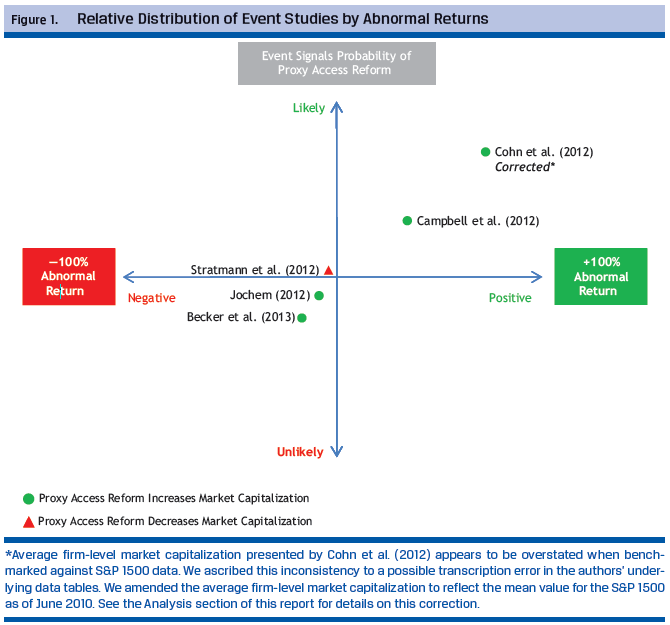

With respect to the relative distribution of findings across studies, four studies affirm that proxy access contributes to an increase in shareowner wealth and one study does not affirm this hypothesis (Figure 1). Two studies are excluded from the analysis because the estimated abnormal returns reflect event dates that are not specific to the SEC’s vacated proxy access rule and thus likely do not reflect the market’s reaction to the specifics of Rule 14a-11. The results of these two studies [4] are omitted from Figure 1 and Figure 2, and a discussion of their methodological shortcomings in the context of this impact assessment is provided in Appendix A of the complete publication (available here).

The vertical line (y-axis) in Figure 1 describes the relationship between the occurrence of an event and the market’s expectations about the likelihood of proxy access reform. The horizontal line (x-axis) captures the abnormal return associated with an event. For example, Jochem (2012) found that the market experienced negative abnormal returns following the DC Circuit Court’s decision to rule against proxy access—that is, the decreased likelihood of proxy access resulted in declines in stock prices, suggesting that proxy access is beneficial to the overall market. Hence, in Figure 1, Jochem (2012) falls within the lower left quadrant, with a green circle to illustrate a beneficial impact. Essentially, event studies that result in findings that suggest proxy access is beneficial will fall within the lower left and upper right quadrants; event studies that result in findings that are adverse to proxy access will fall within the lower right and upper left quadrants.

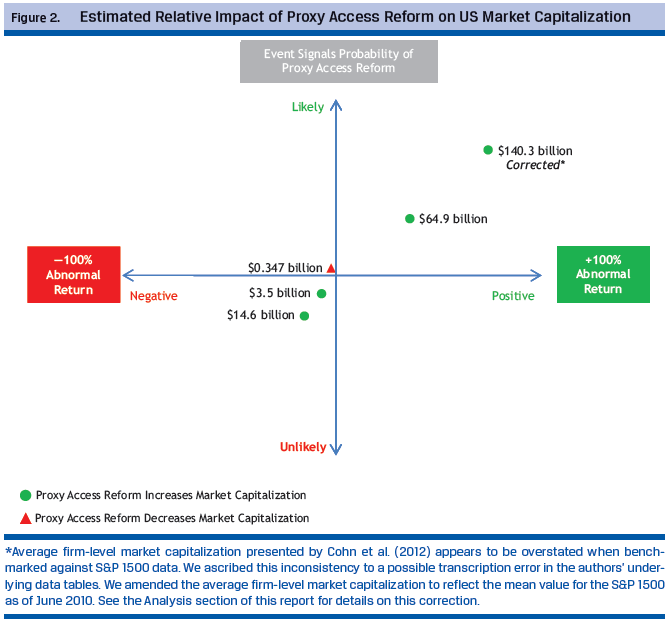

As shown in Figure 2, we extended the study results to estimate the implications for overall US market capitalization. In so doing, we estimated that the average impact of proxy access reform may range from $3.5 billion to $140.3 billion across those studies that evidence a positive relationship between proxy access reform and shareowner wealth. This range reflects the average market capitalization across a sample of firms and event dates, both of which are specific to each event study. [5] When benchmarked against estimated total US market capitalization, as represented by the S&P 1500 for the respective event dates, these estimates reflect between 0.023% and 1.134% of total US market capitalization. [6]

The exception—Stratmann and Verret (2012)—identified a negative relationship between proxy access reform and shareowner wealth. When we extend Stratmann and Verret’s results to estimate potential US market-wide impacts, applying the same assumptions as those discussed earlier, the impact of this negative relationship appears nominal relative to overall US market capitalization. Specifically, the estimated negative impact of proxy access reform on market capitalization is $0.347 billion, which, all else being equal, contributes to a decline in US market capitalization of less than 0.003%. [7]

The Benefits and Limits of Cost–Benefit Analysis

Some of the information we used to examine the potential impacts of proxy access arises from the DC Circuit Court’s decision to strike down the proxy access rule. These event studies were possible because the Court’s decision was a surprise to the markets and thus could not have been priced into the SEC’s initial analysis.

On an ex post basis, the event study technique allows for a before-and-after comparison of stock prices with respect to regulation. When the SEC conducted its cost–benefit analysis of the proposed proxy access rule in 2010, it did not have the benefit of hindsight. Stock price data to assess the market’s valuation of proxy access were unavailable until the SEC passed its proxy access rule in August 2010 (the SEC stayed the rule in October 2010, and the DC Circuit Court vacated it in July 2011). In 2014, with the benefit of hindsight, we can assess the stock price return for firms affected by proxy access relative to those unaffected by proxy access—precisely because a rule was passed and then vacated.

Notwithstanding the brief tenure of the rule, the stock price return for firms affected by proxy access relative to those unaffected by proxy access inherently reflects the market’s valuation of the net impact of proxy access, including nonmarket benefits. For example, if investors expected the benefits of proxy access to outweigh its costs, affected firms should have experienced positive abnormal returns relative to unaffected firms following the implementation of Rule 14a-11. Conversely, if investors expected the costs of proxy access to outweigh its benefits, affected firms should have experienced negative abnormal returns relative to unaffected firms.

Proposed rules such as the SEC’s 2010 proxy access rule have the potential to significantly affect US financial markets. Proxy access could give shareowners a useful tool to help promote greater board accountability, a tool that could be used sparingly and still influence board behavior. In the particular case of proxy access, the event study technique allows the value of proxy access to be quantified, whereas other cost–benefit techniques do not allow for the same degree of quantification concerning economic impacts. The DC Circuit Court’s decision striking down the proxy access rule challenged the SEC’s ability to promulgate rules in the future and, ironically, provided an event that facilitates cost–benefit analysis. For this reason, we decided to consider the event study technique as a means of cost–benefit analysis—a cost–benefit analysis that appears to support the implementation of proxy access.

Analysis of Proxy Access Use in Other Jurisdictions

We also considered how proxy access has been implemented in non-US markets that allow shareowners to place the names of director nominees directly on the corporate proxy. In general, we found that proxy access is used sparingly where it is permitted. In the United Kingdom and Australia, for example, where the style of proxy access in use is similar to that proposed by the SEC, investors have used proxy access to nominate directors for board service an average of fewer than 10 times a year over the past three years.

On the basis of data from the global governance proxy adviser Manifest, we found that over the past three years, proxy access has been used only once in Canada to nominate directors to a board (where it was used successfully). In Australia, proxy access was used 11 times in the past three years, only once successfully. In the United Kingdom, proxy access was used 16 times over the past three years; it was successful on 8 occasions and was defeated 6 times, and nominees’ names were withdrawn on 2 occasions. These data suggest that proxy access is a rarely used shareowner right that is typically used only when other outlets for share- owner concerns about a company or its board—such as engagement between shareholders and companies—have been exhausted or have otherwise proved unfruitful.

Further, preliminary analysis of stock returns among companies that have successfully elected shareowner nominees via proxy access suggests that proxy access has not consistently reduced shareowner value, as its critics might suggest. For example, over the past three years, approximately two-thirds of the companies that elected directors via proxy access experienced positive returns on the day following the vote, and a comparable share also experienced improved performance the year following proxy access relative to the preceding year.

Conclusions

On the basis of our investigation of the available global data, we will discuss in this report the following conclusions in greater detail:

- Limited examples of proxy access and director nominations globally, coupled with the limited availability of corresponding market impact data, challenge whether a more detailed cost–benefit analysis was possible in the context of the Court’s decision.

- The results of event studies suggest that proxy access has the potential to enhance board performance and raise overall US market capitalization by between $3.5 billion and $140.3 billion.

- Assessing and measuring increased board accountability and effectiveness is challenging. None of the event studies indicate that proxy access reform will hinder board performance.

- Proxy access is used infrequently around the world, even where low thresholds for ownership and duration of ownership exist. Evidence in these markets suggests that proxy access has not disrupted the election process in jurisdictions that allow it.

- Likewise, there is limited evidence to suggest that special-interest groups can use proxy access to hijack the election process or to pursue special-interest agendas.

On the basis of these findings, we conclude that proxy access would serve as a useful tool for shareowners in the United States and would ultimately benefit both the markets and corporate boardrooms, with little cost or disruption to companies and the markets as a whole.

We therefore urge the SEC to revisit the issue of proxy access in the United States and to consider all available data in order to conduct the most meaningful cost–benefit analysis possible in assessing whether the proxy access rule benefits shareowners and the market.

Endnotes:

[1] SEC Final Proxy Access Rule http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2010/33-9136.pdf.

(go back)

[2] Business Roundtable and Chamber of Commerce v. Securities and Exchange Commission, slip op. 10-1305 (DC Cir., 22 July 2011).

(go back)

[3] Bo Becker, Daniel Bergstresser, and Guhan Subramanian, “Does Shareholder Proxy Access Improve Firm Value? Evidence from the Business Roundtable’s Challenge,” Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 56, no. 1 (2013):127–160; Joanna T. Campbell, T. Colin Campbell, David G. Sirmon, L. Bierman, and Christopher S. Tuggle, “Shareholder Influence over Director Nomination via Proxy Access: Implications for Agency Conflict and Stakeholder Value,” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 33, no. 12 (December 2012):1431–1451; J. Cohn, S. Gillan, and J. Hartzell, “On Enhancing Shareowner Control: A (Dodd-) Frank Assessment of Proxy Access,” working paper (University of Texas at Austin, December 2012); T. Jochem, “Does Proxy Access Increase Shareowner Wealth? Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” working paper (University of Pittsburgh, August 2012); T. Stratmann and J.W. Verret, “Does Shareowner Proxy Access Damage Share Value in Small Publicly Traded Companies?” Stanford Law Review, vol. 64, no. 6 (June 2012):1431–1468.

(go back)

[4] A. C. Akyol, W.F. Lim, and P. Verwijmeren, “Shareholders in the Boardroom: Wealth Effects of the SEC’s Proposal to Facilitate Director Nominations,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, vol. 47, no. 5 (October 2012):1029–1057; D.F. Larcker, G. Ormazabal, and D.J. Taylor, “The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation,” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 101, no. 2 (August 2011):431–448.

(go back)

[5] If authors reported actual market data for firms in their sample, we relied on those data. There was a subset of event studies for which the authors did not report actual firm-wide market data. In such cases, we applied S&P 500 and S&P 1500 data. The selection of S&P 500 or S&P 1500 data depended on the basket of firms represented in each study’s sample. For example, Becker et al. (2013) defined their sample on the basis of firms in the S&P 1500, whereas Campbell et al. (2012) defined their sample on the basis of firms in the S&P 500. To ensure methodological consistency, we applied data from each index according to the configuration of the specific sample sets, as defined by the authors. See later sections of this report for a more detailed discussion of methodology.

(go back)

[6] Monthly historical data on total US market capitalization are not publicly available. For purposes of deriving market-wide comparisons, we extended monthly time-series data from the S&P 1500 to approximate overall US market capitalization. Standard & Poor’s represents that the S&P 1500 accounts for approximately 90% of overall US market capitalization. For each event date, we estimated total US market capitalization as the aggregate market value of the S&P 1500 on the specific event date divided by 0.90. See http://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-composite-1500.

(go back)

[7] The assessment of impacts on total market-wide US capitalization reflects estimates as of the specific event dates in each study. These event dates range from June 2010 through July 2011. All else being equal, if we scale these impacts to today’s economy on a straight-line basis, using S&P 1500 data to approximate overall US market capitalization as of February 2014, we arrive at a range of potential positive impacts of $4.98 billion to $649.67 billion, with a potential negative impact of $610.58 million.

(go back)

* Copyright (2014), CFA Institute. Reproduced and republished from Proxy Access in the United States: Revisiting the Proposed SEC Rule with permission from CFA Institute. All rights reserved.

Print

Print

One Comment

I will be using this as part of my supporting arguments for all my proxy access proposals going forward.