Ann Yerger is an executive director at the EY Center for Board Matters at Ernst & Young LLP. The following post is based on a report from the EY Center for Board Matters, available here.

Investors’ increasing focus on board composition includes attention to whether boards are continuing to refresh and recruit new directors in line with the company’s changing strategic goals and risk profile. But the challenges of effective board succession planning can go beyond finding new directors whose skill sets, diversity, character, and availability match the board’s needs—they may also include asking long-standing directors to leave the board when appropriate, while protecting directors’ collegiality and relationships.

Based on what the EY Center for Board Matters is hearing from investors and directors, optimal practices for aiding board renewal include robust performance evaluations (including following through on key takeaways), assessments that map director qualifications against a board skills matrix, and creating a board culture where directors do not expect to serve until retirement. [1] Director retirement and tenure policies are also among the tools available to boards to ease transitions. Such policies can help depersonalize the process of asking directors to leave the board.

This post looks at board retirement and tenure policies across companies in the Fortune 100. Using current director ages and tenures across the Fortune 100 and the S&P 1500, it also identifies the portion of directors approaching retirement, based on average retirement-age policies and tenures—and finds opportunity for boards to focus on strategic director succession planning now. [2]

Fortune 100 board retirement-age policies

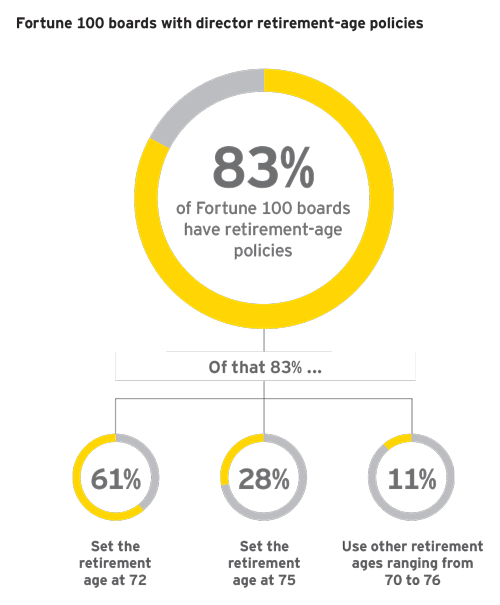

Nearly all Fortune 100 companies have board retirement-age policies in place, with most companies setting the retirement age at 72. Four of these companies have upped their retirement age since last year; none have lowered it.

Among the Fortune 100 companies with retirement-age policies, 19% of directorships are held by individuals within five years of reaching the board’s designated retirement age.

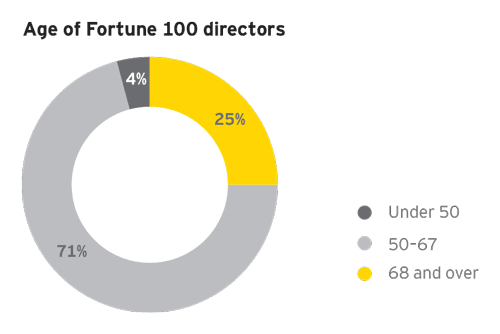

Even when retirement-age policies are in place, some boards may choose to waive them in cases where they feel doing so is warranted. Indeed, nearly half of the Fortune 100 companies that have board retirement-age policies make explicit that the policy may be waived under certain circumstances. Still, it is rare for directors to serve on the board past the set retirement age. Only 2% of Fortune 100 directors are serving on boards past a designated retirement age. In half of those cases, the companies explain in the proxy statement the board’s reasoning for reappointing those directors. Around 8% of Fortune 100 directors are age 72 or older.

Fortune 100 board tenure policies

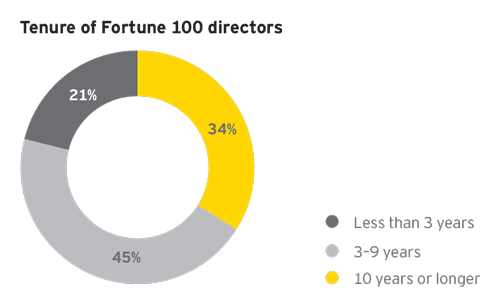

Tenure policies are rare among Fortune 100 companies. Only four companies have them: one uses a term limit of 12 years; one uses 15 years; one uses 18 years; and one uses 20 years. Even when board tenure policies are in place, companies may waive them. In fact most of the companies that do set term limits make clear that the board may make exceptions. Only two Fortune 100 directors are serving on boards past a designated term limit—in one case the director is the chair and CEO of the company, and in the other case the director is the board chair.

Tenure policies are not popular with investors either. Based on EY Center for Board Matters’ investor outreach in advance of the 2015 proxy season, many investors believe that blunt instruments, such as term limits, do not account for the contributions of valuable, long-tenured directors. [3] While some investors will more closely review boards where a significant portion of directors are long-tenured (particularly if they have concerns about other governance practices and/or financial performance), they are generally open to long-tenures when warranted by the director’s contributions and expertise.

Still, some investors did share with us their view that term limit guidelines may provide a built-in mechanism for boards to have a conversation with directors about leaving the board and create additional assessment of long-tenured directors. However, some investors noted that a rules-based path regarding director terms may prove attractive if they perceive that most boards are resistant to refreshing as needed.

How many S&P 1500 directors are currently nearing retirement?

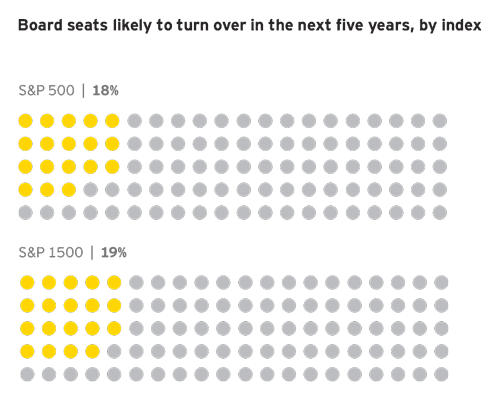

A close look at data on current board members’ ages and tenures shows that 19% of S&P 1500 directorships are held by individuals who are age 68 or older and have served on the board for 10 years or more, up from 14% in 2010. Given that the average retirement-age policy for Fortune 100 companies is 72, we can presume that these S&P 1500 directors—who are within five years of reaching age 72 and, in addition, have tenures of 10 years or longer—are poised to exit the board over the next five years or so. While not a precise measurement, the data reflects that the estimated portion of directors nearing retirement is significant, and greater than it was five years ago.

18% of S&P 500 directorships are held by individuals who are 68 or older and have served on the board for 10 years or more.

19% of S&P 1500 directorships are held by individuals who are 68 or older and have served on the board for 10 years or more.

Conclusion

Factors driving the increasing focus on board composition include the demand that board membership evolve along with a company’s strategic plan and risk profile, the push for enhanced board diversity and related performance benefits, [4] and the need for fresh perspective, expertise and insights in the boardroom, among other things. These goals will not likely be achieved by board retirement or tenure policies alone. Setting expectations upfront that directors will serve for a limited amount of time based on the board’s evolving oversight needs—not necessarily until they reach retirement age—is important. The data showing that a significant number of directors are currently approaching retirement illustrates the current opportunity for boards to review their oversight needs and engage in strategic director succession planning. [5]

Endnotes:

[1] For more on investor views on mechanisms to trigger board renewal, see 2015 proxy season insights: a spotlight on board composition (discussed on the Forum here).

(go back)

[2] All data is from EY’s Corporate Governance Database, which covers more than 3,000 companies listed in the US. Company retirement and tenure policy data is based on the corporate governance guidelines of the 87 publicly traded Fortune 100 companies as of 30 June 2015. Fortune 100 director data is based on most recent annual meeting proxy statements; director data for other indices is based on available 2015 annual meeting proxy statements for meetings through 30 June 2015.

(go back)

[3] For more insights from the Center for Board Matters’ investor outreach program, see 2015 proxy season insights: a spotlight on board composition (discussed on the Forum here).

(go back)

[4] For our most recent report on gender diversity on US boards, see Women on US boards: what are we seeing? (discussed on the Forum here).

(go back)

[5] For tips on effective succession planning for the boardroom, see Let’s talk: governance—Getting it right: succession planning for the boardroom and C-Suite.

(go back)

Print

Print