Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at The Conference Board. This post relates to an issue of The Conference Board’s Director Notes series authored by Jason D. Schloetzer of Georgetown University. The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here. For details regarding how to obtain a copy of the report, contact [email protected]. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here), and The Myth that Insulating Boards Serves Long-Term Value by Lucian Bebchuk (discussed on the Forum here).

The tactics used by activist hedge funds to target companies continue to command the attention of corporate executives and board members. This post discusses recent cases highlighting activist efforts to replace directors at target companies. It also examines the use of controversial special compensation arrangements sometimes referred to as “golden leashes,” the arguments for and against such payments, their prevalence, and the parallel evolution of advance notification bylaws (ANBs) to require disclosure of third party payments to directors.

The allocation of new capital to hedge funds with activist strategies continues to grow. According to Hedge Fund Research, hedge funds that use activism as part of their investment strategy managed $127.5 billion in the first quarter of 2015 compared with only $23 billion in 2002.

While activist funds represent a small fraction of the $2.94 trillion under management by hedge funds in general, activist strategies generate the highest returns of hedge funds deploying any event driven strategy, posting gains of 8.5 percent in 2014, 19.2 percent in 2013, and 9.3 percent in 2012. In the words of Carl Icahn, “There has never been a better time for activist investing.”

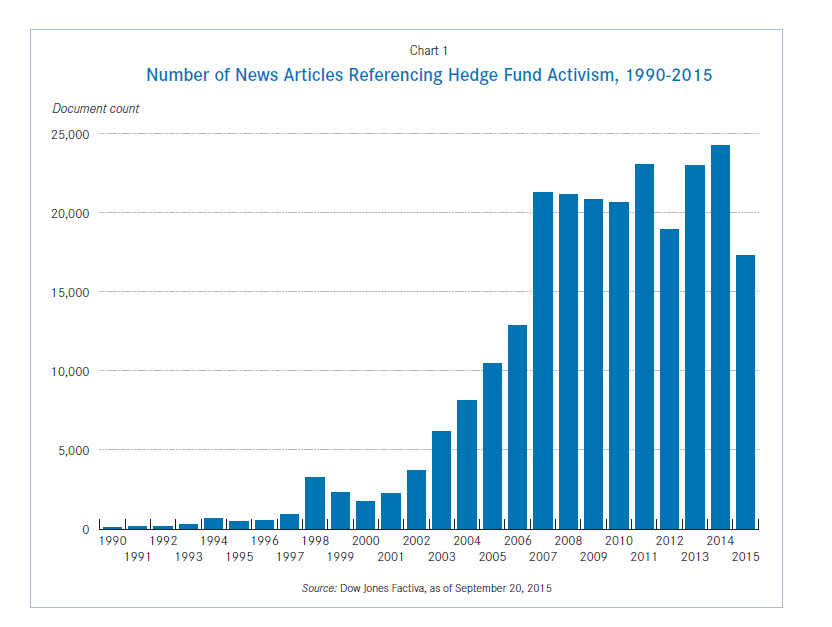

Along with this increase in assets under management, the amount of media attention given to activist hedge funds has exploded. Chart 1 demonstrates this trend. Since 1990, there have been nearly a quarter of a million national and international news articles covering hedge fund activism. This is a relatively recent phenomenon; since 2007 nearly 21,000 news articles on average are written each year about activist hedge fund interventions. To provide perspective on the intensity of media coverage, there were 22,974 news articles about hedge fund activism in 2013, while the law firm Wachtell Lipton identified only 200 instances of activist-investor initiatives in the same year.

Activist Tactics: Target the Board

It is difficult to fully observe the methods activist fund managers use to engage underperforming boards. Activist interventions typically have both private and public components that span multiple years. For instance, a review of 12 large-scale interventions by Carl Icahn’s Icahn Enterprises and Bill Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management showed that, on average, an activist intervention by these funds lasts nearly three years.

One of the principal tactics available to an activist fund manager against a company that fails to take the actions suggested by the hedge fund is to replace one or more members of the board. An analysis conducted by The Conference Board in collaboration with FactSet shows that activist hedge funds led the majority of the proxy contests seeking board representation at Russell 3000 companies during the first half of 2014. The 15 proxy contests mounted by hedge funds for that stated purpose represented 58 percent of the 26 activist solicitations motivated by the election of a dissident’s nominee to the board of directors, and 61 percent of the 25 contests launched by hedge funds during that period. In six cases, the reason for the solicitation was even more hostile, with the investor attempting to gain full control of the board. In 2014, activists gained board seats at 107 companies, an all-time record that appears on pace to be broken in 2015, based on FactSet data through June 30, 2015.

Icahn has said, “[T]here are lots of good CEOs in this country, but the management in many companies leaves a lot to be desired. What we do is bring accountability to these underperforming CEOs when we get elected to the boards.” His statement highlights one key premise of activist hedge fund managers—that targeted companies have managerial deficiencies and fund managers can take steps to discipline boards who fail to maximize shareholder value. To provide perspective on the extent to which activist hedge fund managers will aggressively engage underperforming boards by pushing to nominate dissident directors, it is useful to review recent high-profile actions by JANA Partners, Harry Wilson (on behalf of four funds), Third Point, and Elliott Management.

Harry Wilson/General Motors, Inc.

In February 2015, General Motors announced that it received notice from Harry Wilson regarding his intent to nominate himself as candidate to stand for election to the GM Board of Directors. Wilson was acting on behalf of himself and four investment funds that supported his election: the Taconic Parties, Appaloosa Parties, HG Vora Parties and the Hayman Parties, which together owned approximately 1.9 percent of the company’s shares. The parties sought GM to repurchase $8 billion of shares by the 2016 annual meeting.

By March, General Motors had agreed to repurchase $5 billion in stock in exchange for an agreement with Wilson and the four investment funds to drop the request for a seat on the board. A buyback was already under consideration and investor talks sped it up. GM officials determined that its $25 billion in cash was enough to fulfill spending plans and handle uncertainties, including a federal investigation into an ignition-switch recall. GM finance chief Chuck Stevens said during a conference call, “We believe an initial $5 billion share buyback is good for our owners because we cannot earn better returns by investing that cash in the business at this time.” Moody’s called the buyback a negative credit development, stating, “This program weakens GM’s positioning at the current rating level and will likely delay any potential consideration for an upgrade.” The ratings firm said the key credit risk was GM’s decision to fund the repurchase by reducing the liquidity position of its automotive operations by about $5 billion in the face of a number of operational and financial challenges.

GM acted quickly in repurchasing shares—in the nine months ended September 30, 2015 the company repurchased 85 million shares of outstanding common stock for $2.9 billion as part of the common stock repurchase program announced in March 2015.

Third Point/Dow Chemical Co.

In January 2014, Third Point announced that the fund’s largest investment was in Dow Chemical. Activist investor Dan Loeb, principal of Third Point, indicated in his quarterly investors letter that,

“Dow shares have woefully underperformed over the last decade, generating a return of 46 percent (including dividends) compared to a 199 percent return for the S&P 500 Chemicals Index and a 101 percent return for the S&P 500. Indeed, in April 1999, nearly 15 years ago, an investor could have purchased Dow shares for the same price that they trade at today!”

Third Point proposed that Dow separate its petrochemical business into a standalone company to improve Dow’s strategic focus. In response, Dow stated it would “continue an open dialogue to further enhance value for all of our shareholders.” By May, Loeb again called on Dow’s management to “focus on what is driving this underperformance and how to cure it,” and boldly stated, “Dow’s integrated strategy does not maximize profits.”

Within months, the proxy battle heated up. In November, negotiations between the two sides over board seats broke down after Dow, which had reportedly taken issue with Third Point’s plan to pay its director nominees bonuses, instead offered to expand its board by adding two directors who had previously served on other boards with Dow CEO Andrew Liveris. Third Point had rejected Dow’s proposed directors. Within days, however, Dow avoided a proxy battle by agreeing to add four independent directors to its board—two directors selected by Third Point, and two selected by the sitting directors. Under the settlement terms, Dow also agreed to reduce the size of its board from 13 to 12 members before its annual meeting in 2016, and Third Point agreed to a one-year customary standstill and voting agreement.

As the expiration of the one-year standstill agreement drew near, Liveris met with key long-term investors and portfolio managers to convey its strategic priorities. Liveris noted that Third Point’s tactics have been a distraction, forcing the firm to defer resources from day-to-day business. Liveris also emphasized how Third Point’s strategies have borne little fruit during the standstill period, and that significant changes have been made in corporate governance to address shareholder concerns. “Regular engagement with shareholders on a variety of financial and governance topics is a best-in-class discipline and the very foundation of healthy investor outreach.

Dow has been very clear about our strategic priorities, and our financial performance over the last three years demonstrates both the value of our strategy and quality of our execution against it,” a Dow rep told CNBC. “We welcome ongoing opportunities to engage with our owners on these topics.”

Elliott Management/Hess Corp.

In January 2013, Elliott Management announced that it was nominating a slate of five independent directors as part of broader effort to bolster Hess’s share price after accumulating a 4.5 percent stake in the company between late 2012 and early 2013. Elliott proposed a “substantial strategy change,” which included shedding assets and spinning off valuable shale holdings. Hess’s management indicated that Elliot had contacted the company in mid-January, approximately 120 days prior to Hess’s annual meeting date.

As is common in activist actions by hedge funds, Elliott targeted Hess for a lack of focus. Elliott stated that Hess was “distracted” by its ventures outside its core business, including the company’s financing of fuel cell technology. The hedge fund also criticized Hess’s use of capital, noting the company had not engaged in a share repurchase program despite the rise in oil prices. More explicitly, Elliott believed that Hess’s management had “disregarded the opportunity to learn that the rest of the industry might not have thought too highly of the holes into which the company was pouring billions of dollars of shareholder capital.”

Hess is notable for its vigorous, public response to Elliott’s claims, and the emphasis on how its business dealings were tied to realizing its long-term strategic objectives:

- January 28, 2013: Hess announces that it will exit its refining business and pursue the sale of its terminal network. John Hess, Chairman and CEO, states, “By closing the Port Reading refinery and selling our terminal network, Hess will complete its transformation from an integrated oil and gas company to one that is predominantly an exploration and production company and be able to redeploy substantial additional capital to fund its future growth opportunities.” This announcement comes the day before Elliott discloses that it sent a letter urging Hess shareholders to elect a slate of five independent directors at the 2013 annual meeting and advocating Hess management to conduct a full strategic review in light of lagging performance.

- March 4, 2013: Hess announces several new strategic initiatives to bolster its focus on becoming a pure play exploration and production company, and proposes a slate of five independent director nominees for the 2013 annual meeting and a sixth independent director for the 2014 annual meeting. Hess also discloses a presentation to shareholders providing a detailed analysis of why Elliott’s recommendations are “flawed and irrelevant.”

- March 26, 2013: Hess sends a letter urging its shareholders to reject Elliott’s slate of directors.

- March 28, 2103: Hess announces the sale of assets located in the Caspian Sea. John Hess notes, “This sale is another step in the execution of our strategy to become a more focused, higher growth, lower risk pure play exploration and production company. Consistent with our announcement on March 4, the after tax net proceeds from this sale will be used to pay down an equivalent amount of short term debt.”

- April 1, 2013: Hess announces the sale of assets located in Russia. John Hess notes, “We are making excellent progress in executing our asset sales program, which is a central component of our plan to transform Hess into a more focused, higher growth, lower risk pure play exploration and production company. Just as important, by applying the proceeds from these divestitures to reduce debt and strengthen our balance sheet, Hess will have the financial flexibility both to fund its future growth and also to direct most of the proceeds from additional asset sales to returning capital directly to its shareholders.” Hess notes that the total after tax proceeds from recent divestitures has reached $3.4 billion.

- April 2013: Hess sends four additional letters urging shareholders to reject Elliott’s slate.

- May 2013: Hours before its annual meeting, Hess agrees to give Elliott three board seats in exchange for the hedge fund’s support of the company’s slate of five directors. Hess also agrees to separate the roles of chairman and chief executive and to re-elect directors on an annual basis. Elliott ceases its planned use of special compensation arrangements for its slate of directors (see section below).

- July 2013: Hess announces an agreement to sell its energy marketing business for $1.025 billion as part of the previously announced plan to transform itself into a pure play exploration and production company. This sale, the fifth in 2013, brings its year-to-date divestitures to $4.5 billion. Hess states that the proceeds from its previously completed asset sales have been used to repay $2.4 billion of debt and further strengthen the company’s balance sheet for future growth. The company states that the proceeds from the sale of energy marketing will allow the company to begin repurchasing shares under its existing $4 billion share repurchase authorization.

- October 9, 2013: Hess announces an agreement to sell its US East Coast and St. Lucia terminal network for $850 million in cash, bringing its total year-to-date divestitures to $5.4 billion.

- December 2, 2013: The company announces two separate agreements to sell its interests located off the coast of Indonesia for $1.3 billion. Hess states that it will use the proceeds from these sales to continue repurchasing shares. The sales bring total year-to-date divestitures to $6.7 billion.

- January 8, 2014: Hess files a registration statement with the SEC regarding the potential terms and conditions of a spin-off of Hess Retail Corporation. Hess will also solicit offers to purchase the entire retail business from potential buyers.

- January 29, 2014: Hess announces an agreement to sell approximately 74,000 acres of its dry gas acreage in the Utica Shale for $924 million. Proceeds will be used for additional share repurchases in excess of those associated with the divestiture program announced in March 2013. Hess also stated that it would review whether to seek an increase to its existing $4 billion share repurchase authorization after a final decision is made either to spin off or sell Hess Retail. The sale brings total divestitures since Elliott’s intervention to approximately $7.8 billion.

- April 23, 2014: announces the sale of its assets located in Thailand for $1.0 billion. Hess stated that the proceeds from this sale will be used to continue repurchasing shares under its existing $4 billion authorization. The sale brings total divestitures since Elliott’s intervention to approximately $8.8 billion.

- May 22, 2014: Hess agrees to sell its retail business to Marathon Petroleum Cor. for $2.6 billion. Proceeds will be used for additional share repurchases and the company increased its existing share repurchase authorization from $4 billion to $6.5 billion. John Hess states, “The sale of our retail business marks the culmination of our strategic transformation into a pure-play exploration and production company.”38 The sale brings total divestitures since Elliott’s intervention to approximately $11.4 billion.

- July 30, 2014: Hess announces that it will pursue the formation and initial public offering of assets related to its Bakken oil shale strategy.

- July 1, 2015: Hess completes the sale of a 50 percent interest in its Bakken midstream assets for $2.7 billion, bringing total divestitures since Elliott’s intervention to approximately $14.1 billion, and represents the last announced asset sale.

It is difficult to know the extent to which this series of asset sales were the result of Elliott’s intervention, or whether Elliott’s presence accelerated a pre-defined strategy. The hedge fund apparently supported the divestitures, as Elliott was Hess’s top institutional holder as of March 31, 2015.

Jana Partners/Agrium, Inc.

In November 2012, JANA Partners disclosed phone calls and meetings between its representatives and Agrium management relating to the company’s capital allocation, cost management, and corporate structure. JANA has also held numerous public presentations and circulated letters stating its views with respect to the company’s management and strategy. After what JANA characterized as the board’s “inadequate response,” the hedge fund nominated four independent directors plus the principal for election to the board at Agrium’s 2013 annual meeting. JANA issued a press release announcing its intention to nominate its slate of directors for election to the board.

By February 2013, the boardroom drama was heating up. JANA reiterated its views on the limitations of Agrium’s strategy and the overall failure of the board to make change. JANA’s main complaints related to a lack of cost management in Agrium’s retail division, a lack of disclosure on its retail operations, a refusal to curtail investment in underperforming assets and distribute more cash to shareholders, and a general lack of existing board members to provide the advisory skills necessary to operate a large retail operation.

As the proxy battle was coming to a head in the days before the company’s April 2013 annual meeting, JANA believed it had secured enough votes to elect two of its directors (rather than the original target of five directors) to Agrium’s board. However, this was not the case. At the annual meeting, Barry Rosenstein of JANA accused the company of successfully lobbying after the cutoff to have votes for JANA directors revoked. Rosenstein went as far to say that “this tainted vote is not the end of the story.” He further stated during the company’s annual meeting, “I congratulate you [Agrium’s management]. You are a board that proved that if you play dirty enough, violate all precepts of good corporate governance, fair play, ethical behavior and democracy, you can still lose the campaign but then barely manufacture a victory after the voting is supposed to be over.”

While JANA stated that it would “investigate the vote changes after the voting deadline and of course the vote buying, and to pursue all appropriate remedies,” by October 2013, it had reduced its stake in Agrium to 2.7 percent; by February 2014, it had exited Agrium.

Evolution of Special Compensation Arrangements

These cases highlight the extent to which activist hedge fund managers will aggressively engage underperforming boards by pushing to nominate dissident directors. In addition, each of these cases involved so-called “golden leashes” in which an activist privately offers to compensate its nominee directors in connection with their service as a director of the target corporation. In particular, in addition to a cash payment for agreeing to participate in the proxy contest and/or for succeeding in the contest, nominees receive compensation paid directly by the fund that is contingent on how the stock price of the target company performs over some time horizon.

“Golden leashes” and advance notification bylaws designed to counteract such arrangements (discussed on detail below) have provoked significant controversy since the 2013 proxy season when their use received attention in the Hess/Elliott Management and Agrium/JANA Partners interventions. It is difficult to determine the frequency with which hedge funds use such arrangements, particularly those that tie director compensation to the future performance of the target firm, as there is no specific requirement under the current US securities rules for the disclosure of (i) compensation arrangements between a board nominee and the nominating shareholder, or (ii) conflicts of interest presented by compensation arrangements between a nominee and a nominating shareholder in contested proxy solicitations.

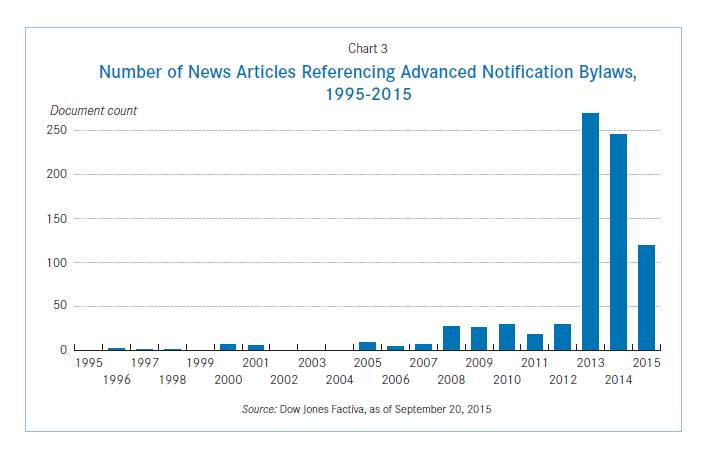

It is likely, however, that the use of golden leashes is rather limited in practice. Chart 2 demonstrates the results of a Dow Jones Factiva search of major national and international news outlets. There is no mention of special compensation arrangements for dissident directors put forth by activist hedge funds in 2010-2012. There is a spike in coverage to 38 articles in 2013, mostly regarding the JANA/Agrium and Elliot/Hess cases. Chart 2 further shows a decline in coverage for 2014 and 2015, although a handful of articles remain, mostly regarding the Third Point/Dow Chemical case. This is suggestive of special compensation arrangements having limited disclosure in practice.

As discussed below, arrangements used since the 2013 proxy season vary but typically include compensating nominees who are appointed to the board by either election or appointment based on achieving performance benchmarks, such as an increase in share price over a fixed term. These performance-based incentives are provided only to the activists’ dissident directors, not re-elected incumbent directors.

Harry Wilson/General Motors, Inc.

In the General Motors case, Harry Wilson disclosed that he would receive a percentage of the group’s profits from their investment in GM. In particular, Wilson would be reimbursed up to $1 million of his GM-related expenses. His compensation arrangement with Appaloosa Management would pay Wilson a performance fee of 2 percent of the appreciation of a portion of the hedge fund’s stake in GM valued at $300 million over the next year and an annual management fee of 0.25 percent of that stake. The payments are contingent on Wilson’s ability to get the share repurchase resolution passed. Wilson’s arrangement with Taconic Capital would pay him a performance fee of up to 4 percent of the appreciation of 3.2 million GM shares held by Taconic, and a management fee of 0.25 percent of that stake.

Third Point/Dow Chemical Co.

Third Point agreed to pay its two nominees $250,000 in consideration for their agreement to serve as nominees. In addition, if appointed to the board by election or settlement, the nominees would receive a second cash payment equal to $250,000, which must be invested in Dow shares if the nominee did not own at least $250,000 of Dow shares at the time of such payment. The nominee would be eligible for two stock appreciation payments, regardless of whether Third Point remained a shareholder. The first payment would be based on the average selling price of the shares during the 30 days before the third anniversary of the date when the nominees began serving on the board; the second would be based on the average selling price of the shares during the 30 days before the fifth anniversary of that date.

In November 2014, Dow agreed to add two Third Point nominees to the board, making these nominees the first activist-nominated directors to serve while having a special compensation arrangement. Ahead of Dow’s May 2015 annual meeting, ISS gave “cautious support” to the compensation arrangements for the directors in the Third Point/Dow case, stating: “For the directors who hold these compensation arrangements, acting in the best interest of all shareholders, even if not in line with a strategy favored by Third Point, will have no adverse impact on the vesting or payout of these grants.”

Elliott Management/Hess Corp.

Elliott Management agreed to pay bonuses to its five nominees measured by each 1 percent that Hess shares outperform the total rate of return over the next three years on a control group of large oil industry firms. The maximum payment to a nominee director was set to be $9 million. Elliott eventually dropped the proposed compensation arrangements in the days leading up to the shareholder vote. The decision was due in no small part to the negative media scrutiny brought by the stinging remarks circulated in a Hess press release to its shareholders, which stated:

ISS operates under the assumption that the dissident will not introduce a disruptive element to the board, despite the fact that each of Elliott’s nominees has signed on to a special compensation scheme that could balkanize the board and create misaligned incentives. In this case, the issue of timing is critical. The Elliott compensation plan expires after a three-year period and Elliott’s nominees have only three years to garner for themselves the cash payout. Although ISS threatens compensation committees with ouster if they do not strictly adhere to ISS’ compensation schemes—without regard to the quality of the director or the company—ISS is willing to enthusiastically support directors who sign on to special short-term compensation packages paid directly by dissidents, the appropriateness and legality of which have been questioned by leading independent legal experts.

Despite the fact that ISS’ view that $9 million ‘‘is probably not going to work as incentive for men such as Harvey Golub because he’s ‘far wealthier than that,’ it is beyond belief that Elliott’s nominees would not be financially motivated to take excessive risks by pursuing short-term, ultimately value-destructive actions rather than make deliberate judgments with the longer-term view for the benefit of all Hess shareholders.

Inasmuch as Elliott’s nominees have only three years to guarantee a cash payout, they are motivated to pursue short-term goals in an industry that requires long-term patience. As any E&P professional will attest, it typically takes at least five to seven years to bring a project from exploration to first oil or first gas, and that process always carries with it a certain amount of execution risk. That risk is compounded by uncertainty, which creates a ripple effect through current and potential joint venture partners, employees, and ultimately negatively impacts shareholders. ISS, like Elliott, is not an oil and gas expert and does not appear to understand that destabilizing the boardroom by introducing a divisive element creates significant risk for shareholders at a time when Hess is executing well on its market-endorsed plan.

Jana Partners/Agrium, Inc.

JANA agreed to reimburse the nominee for all travel and other expenses related to serving as a nominee, and provide $50,000 to compensate the nominee “for the time and effort associated with serving as a member of the slate.” In addition, in this case, if elected to the board, the nominee would be offered to participate in a “profit participation amount” equal to a percentage of the net profits earned, if any, from JANA’s investment in Agrium tied to the closing price of Agrium shares on the trading day prior to the date when the nominee was elected director. This bonus was to be paid either on the date of JANA’s exit from Agrium or “on the third anniversary” of the nominee’s appointment to the board if JANA remained an Agrium shareholder.

JANA faced significant negative publicity—fueled by Agrium’s board—of special compensation arrangements. In a letter to Agrium shareholders, which included the section titled, “JANA’s Dissident Nominees: Bought and Paid For?” Agrium’s Board Chair Victor Zaleschuk explained:

“It is important to note that JANA’s dissident nominees have agreed to accept special incentive payments from JANA for serving on Agrium’s board. These payments are structured to incentivize short-term actions, even if they are taken at the expense of greater long-term value. This kind of ‘golden leash’ arrangement is unheard of in Canada and raises serious questions about the independence of JANA’s nominees, and their ability to act in the best interests of all shareholders.”

Some governance commentators criticized the special compensation, stating:

“Jana’s representatives have a financial incentive to make decisions in Jana’s interests, even if they run counter to the interests of other shareholders … This looks like a real conflict of interest.”

“It’s a concern that this kind of incentive arrangement paid by a particular shareholder detracts from that clear line of duty and who you owe your responsibility to.”

“By compensating directors on the same board differentially, this risks conflict as some directors may question the motivation of other directors when debating options before the board…it may split the board with perceived alliances among some directors and managers.”

The Arguments For and Against Special Compensation Arrangements

The attention received in the Hess and Agrium cases of the special compensation arrangements proposed by Elliott and JANA, respectively, ignited a debate over the merits of such arrangements. In principal, the debate mirrors that of the larger discussion on the appropriate design of executive compensation plans—the amount of emphasis that should be placed on stock price appreciation, and how best to balance short-term performance with long-term value creation. Commentators rarely discuss the specific design of individual compensation arrangements but rather debate the general notion of the appropriateness of third parties providing performance-based compensation to their nominees.

Arguments in favor of special compensation arrangements

The main argument in support of special compensation arrangements is that they help hedge funds to attract high-quality director candidates and align their interests with those of shareholders, including the nominating hedge fund. The challenge that they pose is how to design such incentives for the nominees, particularly (i) the performance measure used to promote incentive alignment and (ii) the time horizon across which to measure performance. With regard to performance measurement, the compensation arrangements in Agrium, Hess, Dow Chemical, and General Motors defined performance simply as stock price appreciation. Proponents of such compensation arrangements agree that an emphasis on stock price appreciation is warranted, while critics generally argue that they focus excessively on stock price, perhaps at the expense of overall firm value. A typical argument in favor of the use of special compensation arrangements is summarized as follows:

“While activism, or the threat of it, is already beneficial, there are strong reasons to believe that supplemental pay would enhance these benefits. The ability to attract top-flight candidates to an activist slate would have positive impact on both companies that are targeted by the activist and those who are not. [S]ince attracting better candidates would improve the activist’s chances to win a potential proxy fight, this would serve as a more effective deterrent tool ex-ante, making management more accountable to shareholders, since they would know that the chances of a successful bid are higher.”

Arguments against special compensation arrangements

The opposing arguments are more varied. There are two root concerns regarding potential unintended consequences. First, critics of such arrangements often argue that a short-term focus on stock price exacerbates dissidents’ tendencies to maximize current value at the expense of long-term firm stability and performance.

At Agrium and Hess, the payments would be made after three years; at Dow Chemical, payments would be made after three years and five years; and at General Motors, payment would be made after one-year. General Motors presents an example that could be used by opponents of such compensation arrangements. After General Motors launched a share repurchase program to avoid a potential proxy contest with the four funds supporting Wilson as a dissident nominee, the credit rating agency Moody’s stated, “This [share repurchase] program weakens GM’s positioning at the current rating level and will likely delay any potential consideration for an upgrade.”

The second concern often raised by opponents of special compensation arrangements is that the compensation is paid by a third party, rather than by the company. This raises the concern that the compensation structures compromise the authority of the board and the independence of the fund’s nominees. Relatedly, others argue that the presence of some directors on the board with such incentives threatens board cohesion, creating a board comprised of dysfunctional, competing groups of directors who are unable to act in shareholders’ long-term interests.

A typical argument against the use of special compensation arrangements is summarized as:

“Some activist hedge funds have begun the unfortunate practice of providing their constituent directors with special compensation arrangements, some of which are contingent on certain events or on the implementation of the shareholding entity’s plans for the company. These arrangements are deeply problematic, as directors—regardless of who nominates them—owe fiduciary duties to all shareholders of the company and should not be prioritizing any particular agenda for personal benefit.”

Target Company Response: Advance Notification Bylaws

In parallel with these actions, boards of directors have started to enact special provisions regulating the ability of proponent shareholders, such as hedge funds, to propose competing directors for consideration at the annual meeting. These provisions typically take the form of advance notification bylaws (ANBs), and are justified by their proponents on the basis that ANBs provide an orderly procedure for, rather than an impediment to, shareholder action, and assure that the company and other shareholders have adequate time to evaluate proposals put forth by activists.

ANBs typically advanced the date by which shareholders are required to submit to the board, often 60 or 90 days prior to the expected annual meeting date, any proposals or director nominees that shareholders propose for consideration at the meeting. These ANBs also require the proponent shareholder to include in the notification the same basic information about the shareholder, and if applicable the nominees, as required by the proxy rules.

However, by advancing the date by which an activist shareholder must notify the company of its intention to take action at the annual meeting, these bylaw provisions force shareholders to commence an activist campaign far in advance of the meeting. And as activist efforts to seek broad-sweeping changes in the boardroom have increased, ANBs have become a tool by which potential target companies can control, or even impede, activist actions at the annual meeting.

As the general threat of activism increased, and the methods used by funds to create change evolved, some companies modified their ANBs to include requirements for extensive disclosure from proponent shareholders, and in some instances, require the completion of company-drafted director nominee questionnaires, establish minimum holding periods and levels of ownership, require continuous disclosure of derivative positions, and disclosure of special compensation arrangements.

Language for a special compensation bylaw amendment was proposed in May 2013 by the law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. This “Wachtell Bylaw” recommended the following:

“No person shall qualify for service as a director of the corporation if he or she is a party to any compensatory, payment or other financial agreement, arrangement or understanding with any person or entity other than the corporation, or has received any such compensation or other payment from any person or entity other than the corporation, in each case in connection with candidacy or service as a director of the corporation; provided that agreements providing only for indemnification and/or reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses in connection with candidacy as a director (but not, for the avoidance of doubt, in connection with service as a director) and any pre-existing employment agreement a candidate has with his or her employer (not entered into in contemplation of the employer’s investment in the corporation or such employee’s candidacy as a director), shall not be disqualifying under this bylaw.”

Wachtell noted that adopting this bylaw would not prevent an activist from nominating candidates, reimbursing their expenses and indemnifying them in connection with the solicitation, or from providing customary compensation to nominees for their efforts if they are not elected (if they are elected they would normally receive director compensation as fixed by the board). In addition, the bylaw would not disqualify a principal or employee of the nominating hedge fund (or other nominating shareholder) from director service on account of the fact that his or her compensation from the fund may depend in part on the price of target company shares owned by the fund.

The proposed bylaw amendment was met with resistance. Most notable was the backlash from ISS, which recommended that shareholders withhold their votes from directors at Provident Financial Holdings, Inc. because the bank had adopted the Wachtell Bylaw. According to ISS, the adoption—without shareholder approval—of restrictive director qualification bylaws, including those that target directors who receive third-party compensation arrangements, may be considered a material failure of governance “because the ability to elect directors is a fundamental shareholder right. Bylaws that preclude shareholders from voting on otherwise qualified candidates unnecessarily infringe on this core franchise right.”

Consistent with its “Governance Failures” policy, ISS may, in such circumstances, recommend a vote against or withhold from director nominees for material failures of governance, stewardship, risk oversight, or fiduciary responsibilities. Glass, Lewis & Co. maintains that restrictive bylaws could hamper the ability of shareholders to recruit attractive candidates for board service. “The best governance practice for boards wishing to implement a restriction on dissident nominee pay is to allow shareholders to vote upon the ratification of such a bylaw,” the company stated. “As such, we will recommend that shareholders vote against members of the corporate governance committee at annual meetings if the board has adopted a bylaw that disqualifies director nominees with outside compensation arrangements and has done so without seeking shareholder approval.” There have been requests for the SEC to provide interpretive guidance on these issues.

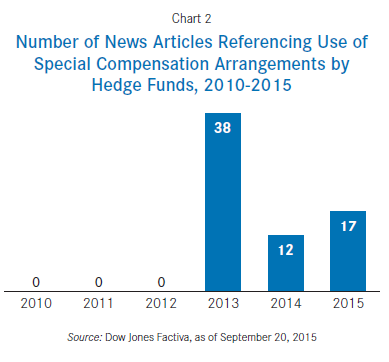

These discussions have not limited the adoption of some form of restriction on third-party compensation arrangements to director. These restrictions mainly take the form of an ANB amendment, and visibility into ANBs in US companies continues to evolve. Chart 3 (page 11) demonstrates the results of a Dow Jones Factiva search of major national and international news outlets.

There is little mention of ANBs through 2007, with an increasing trend in news coverage since 2008, particularly since 2013. A review of the more recent news articles highlights an increased discussion of ANB-related matters during recent proxy seasons. Among more than 4,000 companies tracked by FactSet, roughly 380 have adopted some form of restriction as of October 2015. A review of the 44 companies in the S&P 500 identified by FactSet as having a special compensation disclosure requirement reveals that 26 of these 44 companies use identical or almost identical language in their bylaw; for instance:

“The bylaws restrict director nominee incentive compensation to directors by a third party in connection with the proposed nominee’s candidacy or service as a director of the company that has not been fully disclosed to the company (3rd party director nominee).” [Air Products and Chemicals, Inc.]

“The bylaws restrict director nominee incentive compensation to directors by a third party in connection with the proposed nominee’s candidacy or service as a director of the company that has not been fully disclosed to the company (3rd party director nominee).” [Darden Restaurants, Inc.]

“The bylaws restrict director nominee incentive compensation to directors by a third party in connection with the proposed nominee’s candidacy or service as a director of the company that has not been fully disclosed to the company (3rd party director nominee).” [Halliburton Company]

“The bylaws restrict director nominee incentive compensation to directors by a third party in connection with the proposed nominee’s candidacy or service as a director of the company that has not been fully disclosed to the company (3rd party director nominee).” [Republic Services, Inc.]

“The bylaws prohibit director nominee incentive compensation to directors by a third party in connection with the proposed nominee’s candidacy or service as a director of the company (3rd party director nominee).” [The NASDAQ OMX Group, Inc.]

A requirement to disclose compensation arrangements between the nominating shareholder and its affiliates, on one hand, and its nominees and their affiliates, on the other hand, is particular contentious. To the extent the shareholder has nominated a purportedly independent person to serve as a director, the disclosure of special compensation arrangements at least would serve to confirm the nominee’s independence from the nominating party. However, where the shareholder-nominee is admittedly affiliated with the nominating party (as when an activist hedge fund nominates a principal of the fund), such a requirement essentially discourages an activist from nominating an affiliated party, or suffer public disclosure of private financial information.

One might expect that the boards of companies that adopt special compensation disclosures are dramatically different from other firms in the procedures designed to manage the overall director nomination process. However, it is interesting to note that comparison of the board characteristics of companies that do (“Special Compensation Companies”) and do not require disclosure of compensation arrangements fails to find significant differences between these two types of firms. For instance, Special Compensation Companies are statistically similar to other firms in the rate of using a staggered board and/ or poison pill. Such firms also allow shareholders to call special meetings, to act by written consent (22 percent of Special Compensation Companies allow shareholder to act by written consent compared with 27 percent of other companies), and to allow shareholders to vote on directors selected to fill vacancies.

While opponents of the use of such provisions cast companies as having “bad” corporate governance, the lack of differences reminds us that it remains an open question regarding whether and how the motivation to adopt provisions that require the disclosure of special compensation arrangements fit within a firm’s overall governance culture.

Conclusion

Jana Partners/ConAgra Foods, Inc.

In June 2015, JANA Partners disclosed that it had accumulated a significant position in ConAgra Foods, Inc. JANA sought to place three new directors on the board, arguing that ConAgra’s recent $1.3 billion write down of the value of its acquisition of Ralcorp Holdings, Inc. represented a failed attempt by the board and management to implement its strategy. Within days, ConAgra executives began responding to JANA’s threat by announcing that the company would explore divesting Ralcorp only three years after acquiring the company. In July, ConAgra agreed to add two new independent directors to its board as part of a standstill agreement with JANA.

In this intervention, JANA Partners agreed to pay its nominees $90,000 in consideration for their agreement to serve as nominees. In addition, if elected to the board, the nominee would receive a payment of $140,000. The nominee agreed to invest these payments in ConAgra stock within five business days. The nominee was required to hold these shares until the earlier of (i) the nominee’s resignation from the board or three years from the date of election (or if earlier, the date of any merger or sale), or (ii) if not elected, until at least the earlier of the conclusion of the Annual Meeting and the termination of the Proxy Solicitation.

The Jana/ConAgra case might indicate that a new era of ubiquitous special compensation arrangements is not yet upon us. Rather, there may be a reversion to the compensation arrangements traditionally offered to activist-nominated directors.

It will be interesting to see whether the newest trend in dissident director compensation is simply a reversion to traditional pay methods, or whether innovative performance-based pay practices are forthcoming. Either way, corporate boards and their management teams will continue to grapple with the ever-changing tactics of activist hedge funds.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print