Paula Loop is Leader of the Governance Insights Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop, Catherine Bromilow, Don Keller, Terry Ward, and Paul DeNicola. The complete publication, including Appendix, is available here. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here), and The Myth that Insulating Boards Serves Long-Term Value by Lucian Bebchuk (discussed on the Forum here).

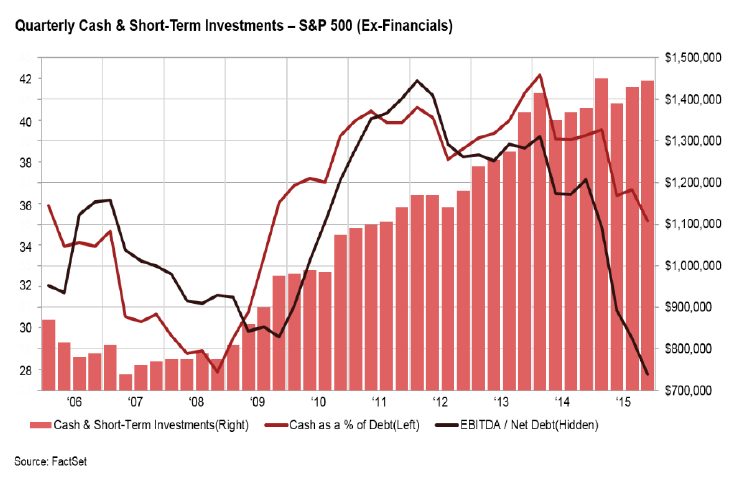

US companies are holding record sums of cash on their balance sheets. In fact, the total cash balance of S&P 500 companies was $1.45 trillion at the end of the third quarter of 2015, representing a 5.8% increase year-over-year. While this phenomenon indicates robust balance sheet health, it also raises questions about the best way to use this liquidity. And these challenges stimulate provocative questions and discussions about the most prudent use of company resources—taking into account different stakeholders’ expectations, the company’s individual circumstances, and the overall economic environment. Ultimately, companies need an effective capital allocation strategy that is well thought-out, linked to their overall strategy, and clearly communicated. And a key element of this capital allocation strategy is whether, and/or how, cash is returned to shareholders.

At the same time, shareholder activism has shifted into high gear. With about $173 billion currently under activist management, proxy contests are more frequent—as are settlements. Activists’ strategies often involve pressuring companies to take one or more of several actions: increase share repurchases, increase dividends, restructure, spin-off a division, or even sell the company. In many of these areas, including increasing share repurchases and dividends, activists have been effective in achieving their goals.

Between 2003 and 2013, S&P 500 companies doubled their spending on share repurchases and dividends while cutting their spending on investments in new plants and equipment. [1] Companies targeted by activists increased spending on share repurchases and dividends to an average of 37% of operating cash flow in the first year after being approached—from 22% the year prior. This trend has been partly fueled by the low-interest-rate environment—enabling companies to borrow money cheaply to finance their share repurchase and dividend programs. So in the face of pressure to boost short-term performance, how should directors and shareholders be thinking about the impact share repurchases and dividends may have on the company’s ability to create long-term value?

A complicating factor for executives and boards is that shareholders are not monolithic. While both activist hedge funds and state pension funds seek a return on investment, they likely employ very different investing time horizons to achieve those returns. They may also have vastly different views about the viability of a particular company’s strategy. Directors need to be prepared to pose tough questions to executives about the virtues of long- and short-term capital allocation strategies. Similarly, investors need to make informed investment and proxy voting decisions based on the interests of their specific constituencies—resisting any urge to follow the lead of those with a different focus.

Share repurchases

One reason companies adopt board-authorized share repurchase plans is that they perceive their shares to be undervalued by the market and want to signal management’s confidence in the company’s future prospects. By repurchasing shares, the company buys its own stock and reduces the total number of its shares outstanding. Because the denominator is lower, the same earnings will increase the company’s earnings per share (EPS). Share repurchases are also a way to offset the dilutive impact of shares issued in acquisitions. Or those treasury shares can be issued to satisfy the equity component of acquisitions or mergers. Repurchased shares can also be used to satisfy the shares needed upon exercise of employee stock options. The effect of these actions can allow a company to remunerate employees at a higher level by issuing more stock options without increasing the number of outstanding shares.

Executives sometimes prefer share repurchases to dividends because they generally require less of a long-term commitment and provide more flexibility. For example, a company may delay or defer an announced plan to repurchase its shares due to unexpected capital needs or changes in stock price. While not ideal, there is generally less negative market reaction to this outcome than there would be to cutting a regular dividend.

There are several different approaches to share repurchases:

- Open market repurchases. The vast majority of share repurchases are on the open market. The manner, timing, volume, and price of these repurchases are governed by detailed rules set forth in the Securities and Exchange Act. In these transactions, companies usually enter into an agreement with a broker or dealer that executes the repurchases according to the companies’ instructions.

- Tender offers. A tender offer is a public offer to shareholders to tender their shares for sale at a specified price during a specified time, subject to the tendering of a minimum and maximum number of shares. This can be done at a fixed price or at a range of prices for a set amount of shares. A company may be more inclined to initiate a tender offer in order to repurchase a large number of its shares at one time.

- Privately-negotiated repurchases. A company can also decide to enter into share repurchase agreements with individual shareholders. This approach is often used when companies want to repurchase a significant number of their shares from a small number of individual investors.

- Accelerated share repurchase programs. These are types of economic hedges that allow, for a fee, a company to purchase a specific number of shares immediately with the final purchase price determined by an average market price over a specified future period. If the average price is higher at the end of the program, the company returns the necessary number of net shares to cover the shortfall. If the share price is lower, the bank delivers more shares. This approach combines the immediate share retirement benefits of a tender offer with the market impact and pricing benefits of an open market repurchase program. However, these transactions are sometimes off-balance-sheet and while they can have a large upside if the shares appreciate, there are also potential risks. Fluctuations in the company’s stock price during the specified period can have a significant economic benefit, or cost, to the company. Companies can find themselves underwater on these contracts if the share price declines. And some critics question whether these practices amount to a company ‘betting’ on its own stock.

Share repurchases can also provide investors with tax advantages when compared to other forms of cash distributions, such as dividends. Dividend distributions are subject to capital gains taxes. By contrast, share repurchases don’t result in a direct distribution, and taxes are generally deferred until shareholders choose to sell their shares.

Share repurchases can also provide investors with tax advantages when compared to other forms of cash distributions, such as dividends. Dividend distributions are subject to capital gains taxes. By contrast, share repurchases don’t result in a direct distribution, and taxes are generally deferred until shareholders choose to sell their shares.

It’s particularly important for directors and shareholders to understand the effect of share repurchases on some of the company’s key performance metrics—as improved ratios can impact executive compensation tied to such metrics. For example, many executive compensation plans are linked to EPS—which increases by repurchasing shares. This can potentially give executives a better chance of reaching bonus targets tied to that measure. Executives also stand to gain if the company’s share repurchases drive the stock price to a level that makes the exercise of their stock options economically beneficial. As a result, some critics of share repurchasing argue that executives’ self-interest is in conflict with their authority to make decisions on making repurchases.

It is also important to assess the appropriateness of the company’s equity and debt structure. Using cash to repurchase shares can put pressure on debt-to-equity ratios and adversely impact a company’s credit rating.

Another consideration for using cash to repurchase shares is that much of that cash may be held in foreign jurisdictions and subject to US taxes upon return of the money to the US (repatriation). The optics of the balance sheet indicate the cash is liquid and available, but a reduction for potential repatriation taxes may not be reflected other than in the footnotes if the foreign cash is considered “permanently reinvested” in the particular jurisdiction. A decision to bring cash home may trigger additional tax expense, thereby reducing what would otherwise appear as cash available for repurchases.

Dividends

Issuing a dividend is another way for companies to return cash to shareholders. A dividend is a cash distribution of the company’s assets, paid on a periodic basis (generally quarterly, annually, or in special circumstances). As of the end of the third quarter of 2015, 85% of S&P 500 companies paid a regular quarterly dividend, and 63% had raised their dividend from the previous quarter. Aggregate S&P 500 dividend payments amounted to $103.3 billion during the third quarter of 2015, and $410.8 billion over the trailing twelve months. [2] Both numbers represented ten-year highs.

Similar to share repurchases, dividends are viewed by the markets as a signal of management’s confidence in the company’s future prospects and financial liquidity. The payment of a dividend will reduce the amount of cash and thus, total assets, on the balance sheet. Because of this, a company’s return on assets ratio (ROA) is enhanced over what it would be absent the payment of the dividend. It will similarly increase the return on equity ratio (ROE), but earnings per share is unchanged. As with share repurchases, it is important for directors to understand how improved ratios might impact triggers for the payment of executive compensation. The achievement of performance targets related to these two enhanced metrics may make bonuses more attainable if dividends are initiated or increased. The reverse may be true if dividends are stopped or reduced. Revisions to the dividend policy that were not anticipated in defining the original compensation program should be carefully considered.

A company’s decision to pay a dividend should be supported by many of the same considerations as a stock repurchase. Specifically, directors and shareholders should understand whether this use of cash is consistent with a reasoned cash allocation strategy. A decision to issue or modify a dividend payment speaks to whether the company believes it can maintain that dividend in the future. Decisions around paying regular dividends are particularly important because the market expectation is usually that the company will continue to pay out the existing dividend. In fact, there is frequently an expectation that the company will raise its dividend periodically. Such dividend increases are viewed by many investors as even stronger forms of assurance that management believes the company has the ability to generate adequate cash to service the enhanced dividend commitments. Conversely, markets generally have a negative reaction to stagnant or reduced dividends.

A company’s decision to pay a dividend should be supported by many of the same considerations as a stock repurchase. Specifically, directors and shareholders should understand whether this use of cash is consistent with a reasoned cash allocation strategy. A decision to issue or modify a dividend payment speaks to whether the company believes it can maintain that dividend in the future. Decisions around paying regular dividends are particularly important because the market expectation is usually that the company will continue to pay out the existing dividend. In fact, there is frequently an expectation that the company will raise its dividend periodically. Such dividend increases are viewed by many investors as even stronger forms of assurance that management believes the company has the ability to generate adequate cash to service the enhanced dividend commitments. Conversely, markets generally have a negative reaction to stagnant or reduced dividends.

While the majority of S&P 500 companies issue regular quarterly dividends, some companies may choose to utilize a “special dividend”—a one-time cash distribution, separate from the regular dividend cycle. One of the benefits of special dividends is that companies can choose to pay them at their discretion without incurring the perceived longer-term commitment that accompanies a regular dividend.

The debt leverage and earnings repatriation considerations relevant to repurchasing shares are also relevant to other uses of cash, including paying dividends.

The complete publication, including Appendix, is available here.

Endnotes:

[1] Vipal Monga, David Benoit and Theo Francis, “As Activism Rises, U.S. Firms Spend More on Buybacks Than Factories,” The Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2015 http://www.wsj.com/articles/companies-send-more-cash-back-to-shareholders-1432693805.

(go back)

[2] Factset, Dividend Quarterly, December 16, 2015

(go back)

Print

Print