Asaf Manela is Assistant Professor of Finance at Washington University in St. Louis. This post is based on a recent article by Professor Manela and Roni Kisin, Assistant Professor of Finance at Washington University in St. Louis, available here.

Capital requirements are an important tool in the regulation of financial intermediaries. Leverage amplifies shocks to the value of an intermediary’s assets, increasing the chance of distress, insolvency, and costly bailouts. Following the recent financial crisis, prominent economists and policy makers have called for a substantial increase in capital requirements for financial intermediaries. Nevertheless, proposals to increase capital requirements face fierce and successful opposition from financial intermediaries, apparently driven by their private costs of capital requirements. Despite the central role of these costs in shaping the regulation, they have not been measured empirically.

In our paper, The Shadow Cost of Bank Capital Requirements, which is forthcoming in the Review of Financial Studies, we use banks’ own actions to infer their perceived compliance costs. Prior to the financial crisis of 2007-2009, banks had access to a costly loophole that helped them bypass capital requirements. Since, according to the banking industry, higher regulatory ratios decrease profitability, a profit-maximizing bank would trade off the cost of the loophole against the benefit of reduced capital. Therefore, data on loophole use, together with information on its costs, reveal the shadow costs of capital requirements. This approach, first used by Anderson and Sallee (2011) to study fuel-economy standards, allows estimation of the shadow costs of regulation without the need to estimate demand elasticities and other unobservables.

To examine this intuition empirically, we set up a simple model and take it to data on banks’ provision of liquidity guarantees to asset-backed commercial paper conduits (ABCP). As documented by Acharya, Schnabl, and Suarez (2013), banks that provided liquidity guarantees to ABCP conduits effectively held the risks of the underlying assets. Instead of treating such guarantees as risky assets, however, banks were allowed to include only 10% (zero before 2004) of these guarantees in the calculation of regulatory capital ratios. Therefore, this loophole allowed banks to decrease their economic capital ratios while keeping their regulatory ratios within the guidelines.

While the loophole benefited banks by relaxing their regulatory constraints, using it was costly, as banks had to pay an incremental cost for using ABCP conduits. Therefore, for constrained banks that use the loophole, the ratio of the marginal cost of using the loophole to its marginal capital relief reveals the shadow cost of the regulatory capital constraint.

Our approach allows us to estimate the shadow costs of capital regulation for constrained banks that used the loophole. We identify 18 U.S. bank holding companies that sponsored and provided liquidity guarantees to ABCP conduits in the pre-crisis period, using detailed data on ABCP conduits from Moody’s Investor Service and banks’ quarterly reports. Although few in numbers, these institutions account for about half of all U.S. bank assets. Consistent with the model, we show that they were much more constrained by capital regulations than the rest of the banking universe. These large, heavily levered banks were at the epicenter of the recent financial crisis, and are still the subjects of (and active participants in) the policy debate on capital requirements.

We derive the marginal capital relief from exploiting the loophole for each regulatory capital ratio (tier 1 risk-based, total risk-based, and tier 1 leverage ratio). The benefits can be calculated using our data; they are higher for banks that achieve a higher reduction in regulatory ratios using the loophole. The marginal cost and incremental cost of exploiting the loophole is harder to quantify. For our baseline estimates, we use the 30-day ABCP spread over financial commercial paper, which is positive and stable during the pre-crisis period. In addition, because this spread may not capture the full marginal cost of exploiting the loophole, we derive an upper bound for it (and hence for the shadow costs) that allows for arbitrary measurement error.

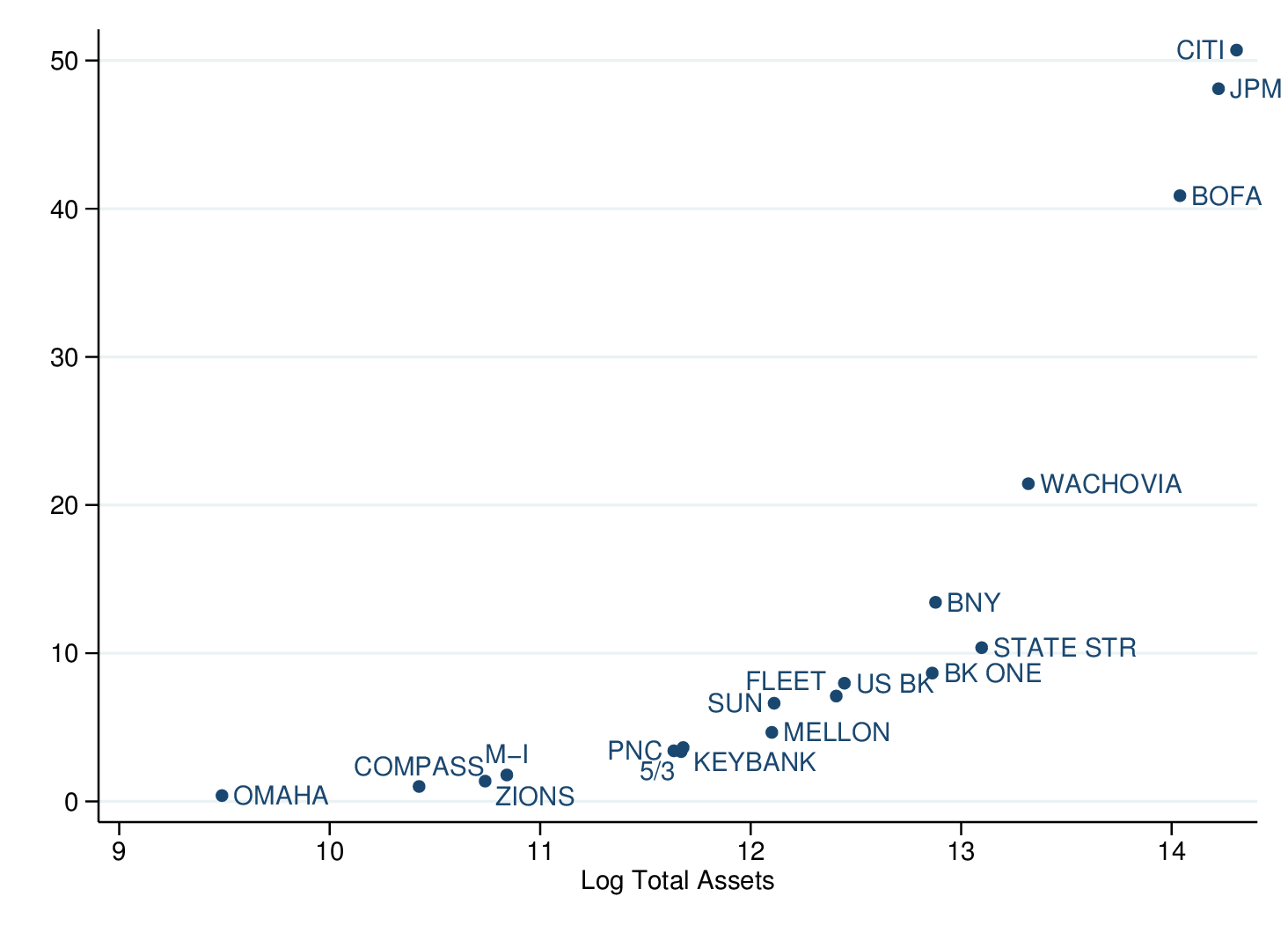

We find that the shadow costs of capital requirements during the pre-crisis period were modest. According to our baseline estimates, which we summarize in Figure 1, a one-percentage-point increase in required tier 1 capital ratios would cost all participating banks combined about $220 million a year ($160 million for the total risk based ratio). The cost to an average bank is $14 million for tier 1 ratios ($10 million for the total risk-based ratio), which corresponds to 0.4% of its annual profits. The upper bounds are about $140 million for tier 1 ratios and $100 million for the total risk-based ratio (23% of annual profits). These bounds, calculated using an intentionally inflated measure of the incremental cost of equity, confirm the baseline results and imply a modest shadow cost of capital requirements.

Figure 1. Decrease in profits ($Mil) from a one-percentage-point increase in the required tier-1 risk-based regulatory ratio

Notes: Time-series averages for ABCP sponsoring U.S. bank holding companies, 2002Q4-2007Q2.

The modest shadow cost may appear puzzling given banks’ resistance to higher capital requirements. Note, however, that we estimate the costs of complying with regulation, rather than the cost of issuing additional equity. We show that modest shadow costs could be due to ineffective regulation, when regulatory ratios do not map into true economic capital ratios. Indeed, a large literature documents that banks avoid regulation by exploiting weaknesses of risk-weighting rules, shifting activities into softer regulatory environments, and using other loopholes.

This suggests a way to use our estimates (combined with information on marginal costs) to gauge the effectiveness of regulation. If equity is costly, a small shadow cost implies that banks can avoid an increase in the economic capital ratios. We find that even under Modigliani and Miller (1958) with taxes, regulators would have to increase regulatory requirements by 10 percentage points to achieve a one-percentage-point increase in economic capital ratios.

What do our results imply about the effect of the recent changes in banking regulation? The latest revision of U.S. regulation (effective January 1, 2015) introduced relatively minor changes, such as the requirement for well-capitalized banks to have a common equity tier 1 capital ratio above 6.5%. Other ratios are increased by small amounts: the tier 1 risk-based and leverage ratios are increased by two percentage points each, and the total risk-based capital ratio requirement is left unchanged. Our estimates imply that these changes will have a negligible effect on bank profits as well as on banks’ economic capital, as banks appear to neutralize the increase in regulatory requirements. While the paper focuses on the pre-2008 period, our approach is readily extendable to study the effects of newly introduced regulatory initiatives, such as countercyclical capital buffers and special treatments of institutions deemed systemically important. Naturally, our framework can use other loopholes, such as structured investment vehicles and letters of credit, to quantify the costs of capital requirements for financial intermediaries.

The full paper is available for download here.

Print

Print