Damien J. Park is Co-Chairman of The Conference Board Inc.’s Expert Committee on Shareholder Activism. This post relates to an issue of The Conference Board’s Director Notes series edited by The Conference Board’s managing director Matteo Tonello. The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Law and Economics of Blockholder Disclosure by Lucian Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson Jr. (discussed on the Forum here); and Pre-Disclosure Accumulations by Activist Investors: Evidence and Policy by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Robert J. Jackson Jr., and Wei Jiang.

Considering the growing amount of capital available to established activists and new entrants, the trend for increasing shareholder activity in the US and globally is likely to continue. This post reviews the first phase of an activist’s campaign and perhaps the most important component of any activist investment strategy: how activists go about identifying undervalued and attractive target companies.

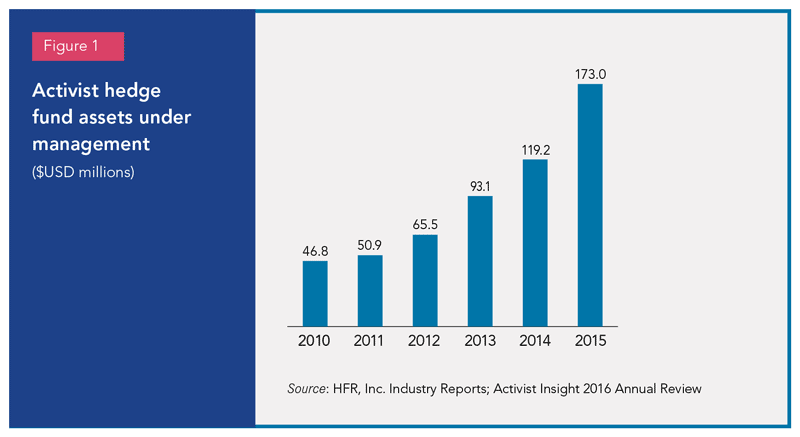

The sheer size of assets under management by activist-oriented investors today suggest that most companies will be affected by activism in one form or another, directly or indirectly (see Figure 1: Activist hedge funds assets under management and Figure 2: Number of US activist campaigns).

With just over three months before a company’s annual meeting of shareholders (AGM), around the same time most publicly-traded companies close the window to accept shareholder-submitted director nomination notices, the chairman of the board and CEO would historically start turning their attention toward the company’s yearly event. What should shareholders know about the company, its prospects, its organizational and governance structure? What are the operational, financial, and systemic risks associated with the business and how are the key value drivers being managed for improved shareholder returns over the next three, five, and ten years?

Ninety days of preparation for this sort of annual assignment may seem more than an adequate amount of time for management to articulate the appropriate message to investors at the company’s AGM. In practice, however, this approach is often inadequate. Over the past fifteen years, understanding, interacting with, and to some degree managing active-value investors—perhaps better known today as shareholder activists—has become a full-year vocation. In fact, companies that refuse to accept this new age of communications between shareholders, management, and board members are in peril of stepping into a trap that may have been set months in advance.

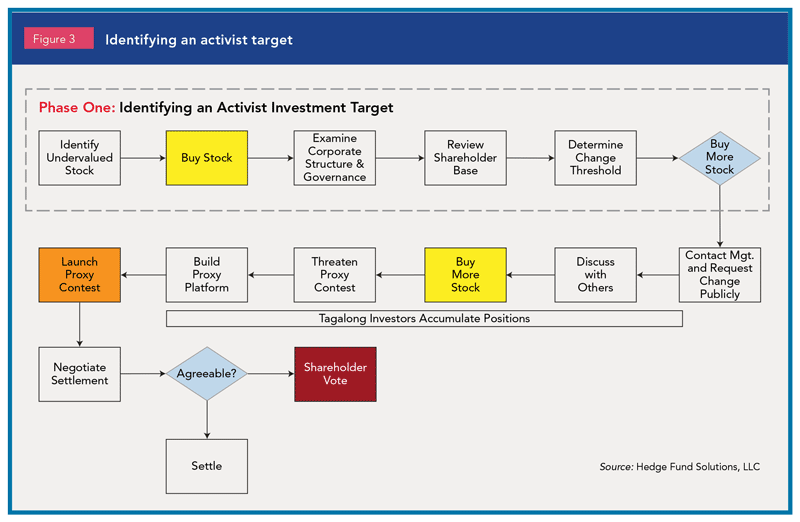

Today, many seasoned activist investors employ a calculated but predictable investing process that can be better understood when segregated and examined into three distinct, yet interrelated categories:

- Identifying a target investment;

- Engaging with a company’s leadership; and

- Managing a successful solicitation effort.

The overarching objective is to obtain sufficient influence with the company’s key decision makers in order to drive more value for shareholders.

This post focuses on the first phase of an activist’s campaign, and perhaps the most important component of any activist investment strategy: how activists go about identifying undervalued and attractive target companies (see Figure 3).

Most people are unaware that by the time an activist campaign hits the headlines of major business journals, the activist hedge fund has spent months (and in some cases years) preparing for it. Investments managed by seasoned shareholder activists often involve a comprehensive and sophisticated analysis of corporate valuations, governance structures, shareholder sentiment, and institutional voting policies. Almost all of this analysis is completed behind-the-scenes and well in advance of holding discussions with management or publicizing specific demands for strategic, operational, and financial changes.

Identify Undervalued Stock

Many activist investors are fundamental value investors that subscribe to the Graham and Dodd philosophy of investing. Benjamin Graham and David Dodd were colleagues at Columbia Business School who taught investors how to identify securities with an underlying value that was not accurately reflected in its publicly traded market value. Eventually, this investing style became universally referred to as value investing, or buying securities having “a margin of safety.”

This thinking is at the core of any activist investment thesis. Activists search for undervalued or underperforming companies where they believe hidden value can be readily unlocked. Following the identification of these assets, activists engage with company management to help bring about the changes necessary to unlock this dormant value.

Like many value investors, activists identify these undervalued securities through a variety of different methods.

Value Screening

The initial part of an activist endeavor often begins with a review of thousands of companies based on a set of economic parameters that is commonly referred to as value screening. And while different investors tailor screens to the metrics they prefer to see, all value investors have a finely honed set of investment identifiers used to screen opportunities in the market. Listed below are a set of the most common variables used by value investors.

- One-, Three-, and Five-year Total Shareholder Return (TSR) From a very basic perspective, TSR is a reflection of a company’s ownership value to shareholders, which is calculated by annualizing an investor’s rates of return that reflect stock price appreciation plus dividend reinvestment and distribution. Activist investors and proxy vote advisory firms such as Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. (ISS) often compare a company’s TSR to defined comparable companies and a relevant stock market index such as the S&P 500 Index in an attempt to evaluate how a business is performing over time.

- Price-to-Book Ratio (P/B) This ratio is used to compare a company’s market price to its book value and is often used by value investors to obtain a comfort for their investment based upon the liquidation value of the company’s tangible assets. However, it must be noted that in recent years, an increasing proportion of the value of companies has come from intangible assets like intellectual property and brand names, which has resulted in higher P/B multiples than ever before.

- Price-to-Earnings Ratio (P/E) This ratio is one of the oldest and most frequently used metrics for valuing a company and is done by measuring its current share price relative to its earnings per share, usually over the last four quarters.

The P/E ratio is sometimes referred to as the price multiple or the earnings multiplier, and is particularly useful for activist investors who will compare the ratio to the price multiple of competitive companies in an attempt to determine whether the stock market is applying an appropriate valuation multiple. Stocks that trade at lower multiples may do so because investors have lost confidence in management, certain business divisions or assets are dragging down the value, the company’s financials are difficult to analyze, or various other factors that an activist may ultimately identify as “fixable.”

- Enterprise Value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA) Unlike a P/E ratio valuation metric, the EV/EBITDA ratio takes into account a company’s debt and is often used by activist investors to determine what a potential acquirer might pay for the business in the event it can be sold. The EV/EBITDA multiple is often compared to similar companies that have been purchased recently by financial or strategic buyers and used to highlight the discrepancy between the company’s current trading value and its potential take-out value.

- Price to Free Cash Flow (P/FCF) is a valuation measure that compares a company’s market price to its annual free cash flow generation, which is similar to a company’s “cash flow” metric but in this case reduces a company’s operating cash flow by the amount a company spends on capital expenditures to maintain its operations. Value investors sometime analyze this metric to determine a company’s capacity to generate cash in excess of its required normal operational usage.

- Current Ratio The Current Ratio is often used by value investors as a quick down-and-dirty way to gauge a company’s ability to pay its short-term and long-term obligations and is calculated by dividing the company’s current assets by its current liabilities.

- Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) also referred to as return on capital, is a calculation used by many value investors, and activists in particular, to determine the effectiveness and efficiency of management’s capital allocation decisions. It provides a reasonable analysis as to how well as company is using its money to generate investment returns.

Other Metrics

In addition to the financial metrics used by typical Graham and Dodd value investors, activists will look closely at other metrics to determine the viability of a company for activism. These include:

- Insider buying/selling (buying and selling activity by managements and boards of directors is often considered a reliable indicator of a company’s outlook);

- Market capitalization range;

- Geographic location of headquarters (different states and countries have different investment regulations); and

- Stock price relative to 52-week high and low.

Analyst Coverage and Wall Street “Orphans”

The investment banking industry went through a dramatic shake-up after the 2008 financial crisis. Some investment banks went completely out of business, others merged, and many cut their sell-side analyst coverage. The impact was felt most in small and mid-capitalization stocks, as these companies typically produced less profit on investment coverage than larger capitalized stocks. Because trading volume in these companies is often small, many investment banks decided to focus on large-capitalization stocks that could generate higher commissions on larger trading volume for the bank. As a result, many small and mid-cap stocks became Wall Street “orphans” with little or no professional investment coverage. These small stocks no longer have the attention of the banks, and thus many institutional investors steer clear of them altogether; all of which is consistent with Graham and Dodd’s theory of profiting from underappreciated, misunderstood stocks.

Low Capitalization

On average, activist investors accumulate six percent of a company’s outstanding shares, which is easier to do if the company has a smaller capitalization. In fact, in 2014 approximately 70 percent of all activist campaigns were directed at companies whose market value was less than US$1 billion. Activist investors will target smaller capitalization stocks in part because it is less expensive to acquire a sizable position. Small-cap companies tend to exhibit more volatility, are under the radar of most investors, lack sell-side Wall Street research, can be more illiquid, trade over-the-counter (OTC), and typically do not communicate the company’s “true” enterprise value regularly and effectively enough with investors. These peculiarities can cause small-cap stocks to trade at a significant discount to intrinsic values and offer opportunities to activist investors to buy them cheaply and push for changes quickly to generate substantial shareholder value.

13F Disclosure Analysis

With the advent of technology trading systems and elaborate quantitative algorithms that are used to track hedge fund holdings, well-regarded value investor disclosures have become a breeding ground for idea generation. A lot of activist investors will analyze quarterly 13F filings with the SEC to find increased ownership positions and new purchases from other like-minded investors. Often, activist investors will find a new stock position being built by a smart value investor during the previous quarter and, upon further examination, can uncover potential activist investment opportunities for themselves.

High Trading Liquidity

An important aspect of any activist play is amassing a critical number of shares in a timely fashion. While there was an earlier discussion on how illiquidity can contribute to a stock being undervalued, high trading volume can be equally as important when an activist investor is attempting to build a large stake over a short period of time. Some activist investors have a following of other investors (obtained, for example, through 13Fs and other SEC filings), and thus have legitimate concerns about others inadvertently driving up the cost of acquisition before they themselves acquire the appropriate ownership threshold needed for change (a topic we take up later). Stocks that exhibit high trading liquidity are helpful to an activist building a substantial ownership position before tag-along investors can catch on.

Undervaluation on a Comparable Basis

Investors can look at a broad set of valuation metrics and comparable companies to help better understand which securities are trading at a discount to intrinsic value and/ or peer value. Activist investors will focus on several factors to identify undervalued securities. For instance, operating margins for a target company vs. competitors could indicate that management is spending too much or not allocating capital in the most efficient manner. Potential profit margins can be obscured by high costs, expenses, sales and marketing, salesforce turnover, low capacity utilization, or a myriad of other issues. Activists might find a low operating margin business attractive if they believe they can reduce certain expenditures and cause EBITDA to become positive in a short period. Also attracting activists’ attention are companies trading at low EV/EBITDA, P/E, P/FCF, or P/B ratios (as mentioned previously). In cases where an activist has the wherewithal to help management streamline a company’s operations, forward-looking projected financials may well offer a drastically distorted picture of underlying profitability, causing most investors and analysts to miss the real value potential of the company.

Sum-of-the-Parts Analysis

Many activist investors will look for companies with multiple business units, often with no synergies between them. Investors will dissect the company into separate business segments and value each by itself, applying different valuation metrics to each business unit. Combining the derived intrinsic valuation calculation from each segment generates a sum-of-the-parts valuation price for the entire company.

One reason activists find companies with multiple operating segments interesting is because they believe certain business units are not being valued properly as part of a larger entity. Thus, activists will develop financial models and an investment thesis relating to a spin-off or sale of certain business units. Tax-free spin-offs have grown widely in popularity, mainly because activist investors have pushed for them more frequently than in the past. The theory is that a new stand-alone business segment will get 100 percent of a management team’s focus. Creation of a separate company also allows the newly created entity to decide the capital allocation structure that is best for its needs, which may differ considerably from a conglomerate or holding company’s objectives. Finally, spin-offs are appealing to potential buyers as pure-play businesses in a single industry.

Net Cash Availability

One telling sign of inefficiency for many activist investors is a large net cash balance (total debt outstanding minus cash available), especially as a percentage of the market capitalization. Investors may believe management teams are not using the company’s cash efficiently, and would prefer to direct the company’s capital allocation decisions in a more efficient way, perhaps through dividend distributions or share repurchases. Activists recognize that cash held on a company’s balance sheet in the current economic environment yields zero percent return for investors and better opportunities may exist elsewhere to maximize the value of that investment.

Excess Debt Capacity

Similar to excess cash, activists are also attracted to companies with unused debt capacity. Investors view companies that are fairly consistent in their cash generation to be a prime candidate to add debt. Companies that have a clear ability to service more debt can often use that debt to generate substantial shareholder value by repurchasing shares, acquiring other companies, or paying out special dividends.

Asset Diversification

As a general rule, targeted companies have more asset diversification than non-targeted companies. As we noted earlier, a target company may have several non-synergistic business units that are likely to have a drag-effect on the value of the overall company. If a stand-alone unit has the potential to perform exceptionally well, while another unit is struggling with declining financials, an activist may prefer to see the units separated so the market will apply a fair value to the better performing unit.

R&D Expenditures

While there are minor exceptions, activist investors tend to stay clear of companies reporting high research and development expenditures because translating research into realized market potential is more often an art than a science, particularly for outsiders. Value investors tend to be simplistic in their thinking about businesses and often put complex companies in the “too difficult to understand” category fairly quickly. It is hard for an outsider to run an activist campaign and provide insights on a company they do not fully comprehend.

52-Week Stock Price Performance

As we mentioned earlier, activist investors look for stocks trading near 52-week lows. These stocks often indicate the company has gone through a bad period, or has disclosed management issues, liquidity concerns, or problems generating growth. By itself this has little meaning, but if an activist investor can decipher what’s behind the depressed results and confidently identify how to improve the situation, this could be an ideal activist-led investment.

GAAP Accounting Masks

The GAAP accounting methods used in target company financial statements can misrepresent underlying profitability and value in several ways, including depreciated real estate assets, complex conglomerate financials, underperforming business units reporting through consolidated holding company P&Ls, and large tax benefits such as net operating loss (NOL) carryforwards. Such “masked” financial statements can cause a company to trade for less than its full value, and activist investors will look to exploit these opportunities to get the market to recognize them fully and generate shareholder value.

Examine Corporate Structure and Governance Provisions

Following a thorough valuation analysis, activists typically acquire a minor ownership position (usually less than 5 percent of the company’s shares outstanding), while continuing the diligence process into other areas such as governance.

Laws of the State of Incorporation

Where a company is incorporated can have a profound effect on the outcome of an activist campaign. For this reason, the business law governing a target company’s state requires a thorough examination from activists and their legal counsel in structuring an appropriate activist investment strategy.

More than 50 percent of all publicly-traded companies in the United States, including 64 percent of the Fortune 500, have chosen Delaware as their legal home. In addition, many states look to Delaware for guidance in developing and interpreting their own corporation law. That said, simply understanding how Delaware law applies to activist investments is insufficient. It’s important that activists understand the subtle nuances and implications that different state statutory provisions may have for an activist campaign. Indeed, a corporation’s legal domicile may determine early on if an activist investment makes any sense at all.

One of the most important provisions governed by states is the business combination rule with interested shareholders. For example, Section 203 of the Delaware General Corporation Law generally restricts a shareholder from making a bid to acquire a corporation for a period of three years after crossing the 15 percent ownership threshold. New York has a 20 percent threshold, Wisconsin’s is 10 percent, and Georgia has a five-year moratorium for those holding shares above 10 percent. Separately, the Pennsylvania Control Share Acquisition Act requires a bidder to prove it has adequate financing before a company is required to do much about it. Pennsylvania also has a “creeping acquisition” provision requiring shareholder approval for investors to acquire more than 20 percent of the shares outstanding.

A state’s corporate law will also set guidelines for a company’s governance structure and the board of directors’ ability to adopt or refine its charter and bylaws. Some of the more important provisions related to shareholder activism include:

- A board’s capacity to amend company bylaws, adjust advance notification provisions, and install supermajority voting requirements;

- The flexibility to employ various forms of anti-takeover devices such as classified boards, poison pills, and poison debt provisions;

- The ability for shareholders to call special meetings (Colorado and Minnesota, for example, have state statutes allowing 10 percent shareholders to call a special meeting to vote on certain shareholder proposals); and

- The ability for shareholders to act by written consent in lieu of a formal shareholder’s meeting.

Impact of Proxy Voting Advisor Recommendations

Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, the two most influential proxy vote advisors, provide regular guidance to companies and investors relating to best-in-class corporate governance practices. Knowing how these two groups will evaluate and recommend votes as a result of a company’s governance provisions is critical to many activists’ campaigns. Following are some important factors considered by ISS and Glass Lewis.

Board member age/tenure The appropriate length of board member service is an emerging corporate governance issue that generates varying responses among large shareholders, proxy advisors, and directors themselves. And while US public companies generally do not have specific term limits on director service (only three percent of S&P 500 companies have term limits, all of which exceed 10 years of service), some companies indicate in their bylaws a mandatory retirement age typically between 72 and 75 years of age.

ISS has stated that it views a director’s tenure of more than nine years as “excessive” and “potentially compromising a director’s independence” and has adopted a policy to scrutinize boards where the average tenure of all directors exceeds 15 years for independence from management and for sufficient turnover to ensure that new perspectives are being added to the board.

It’s also worth noting that Glass Lewis does not subscribe to the same policy as ISS on this matter. In its 2016 Proxy Season Guidelines, Glass Lewis states, “Academic literature suggests that there is no evidence of a correlation between either length of tenure or age and director performance.” However, Glass Lewis goes on to clarify that if a board does adopt term/age limits, it should follow through and not waive such limits. If the board waives its term/age limits, Glass Lewis will consider recommending shareholders vote against the nominating and/or governance committees, unless the rule was waived with sufficient explanation, such as consummation of a corporate transaction like a merger.

Board size ISS will vote against proposals that give management the ability to alter the size of the board outside of a specified range without shareholder approval.

Classification/Declassification of the Board Both Glass Lewis and ISS will recommend shareholders vote against the classification of a board (to stagger a director’s terms, typically over three years) and for proposals to repeal classified boards or elect all directors annually.

CEO Succession Planning In 2009, in a Staff Legal Bulletin, the SEC recognized the significant risk implications of poor succession planning and changed its guidance to allow the submission of shareholder proposals requesting companies disclose their CEO succession policy. As such, ISS says it will generally vote for proposals seeking disclosure on a CEO succession planning policy considering, at a minimum, the following factors: (i) the reasonableness/scope of the request, and (ii) the company’s existing disclosure on its current CEO succession planning process.

Independent Chair and Separation of Chair/CEO roles Within certain parameters and taking into account a company’s current leadership structure, performance, and governance practices, ISS will often recommend shareholders vote for proposals that require a chairman’s position be filled by an independent director. Glass Lewis agrees, believing that the separation of the two roles create a better governance structure.

Majority Vote Standard A majority vote standard requires directors to be elected by at least a majority of the votes cast for their election. While approximately 84 percent of S&P 500 companies use the majority vote standard for uncontested elections, thousands of US companies still use the plurality vote standard.

Glass Lewis believes a majority vote standard is quickly becoming the norm since investors are increasingly supportive of this measure. As such, Glass Lewis is supportive of the adoption of a majority vote standard stating that such a provision will likely lead to more attentive directors. ISS generally recommends in favor of proposals to adopt such a policy but strongly encourages companies to also adopt a post-election policy (also known as a director resignation policy) that will provide guidelines so that the company will promptly address the situation more closely.

Proxy Access Proxy Access is considered shorthand for providing shareholders with the right to place their nominees for directors on a company’s proxy card. Many organizations like the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) are supportive of proxy access, claiming “it would invigorate board elections and make boards more responsive to shareowners and more vigilant in their oversight of companies.”

While proxy access has yet to be fully embraced by activist investors, several larger companies targeted by activists have amended their bylaws to permit investors the ability to nominate directors using the company’s proxy materials (instead of mailing separate proxy materials to shareholders to elect directors). Companies that have recently adopted proxy access include Yahoo!; Apple Inc.; AT&T; Staples, Inc.; and Citigroup.

ISS and Glass Lewis both generally support affording shareholders the right to nominate director candidates to management’s proxy as a means to ensure that significant, long-term shareholders have an ability to nominate candidates to the board. ISS expands upon this slightly, clarifying that its support for proxy access proposals is usually contingent upon the existence of the following provisions:

- Ownership threshold: a minimum requirement of more than three percent of the voting power;

- Ownership duration: a minimum requirement of longer than three years of continuous ownership for each member of the nominating group;

- Aggregation: the aggregate number of shareholders permitted to form a nominating group is below 20;

- Cap: a cap on nominees of generally 25 percent of the board.

Poison Pills and Net Operating Loss (NOL) Protective Amendments Poison Pills, also known as shareholder rights plans, have been contentious instruments for many shareholders since their introduction in 1982 by the law firm Wachtell, Lipton Rosen & Katz following an onslaught of unsolicited corporate hostile takeovers. The term is derived from a “poison pill” physically carried by spies throughout history and taken when they were confronted with being interrogated by the enemy.

By employing a poison pill defense, in general, a company has the right to sell discounted shares if one shareholder buys more than a certain percentage of the company’s shares outstanding, e.g. a 20 percent “trigger.” Once the insurgent shareholder has breached the pill’s trigger threshold, every other shareholder (not including the one who possesses 20 percent) will have the right to buy a new issue of the company’s shares at a steep discount. The net effect is that the insurgent shareholder’s ownership/voting power is muted and its hostile advances are effectively killed through a massive dilution of the company’s shares outstanding in the event the pill is “swallowed” or the trigger threshold is breached.

Poison pills have proven to be an extremely effective takeover defense but are scrutinized much closer today than ever before. ISS, Glass Lewis and many large institutional investors have clear policies relating to the adoption of a poison pill defense tactic and often require that the pill be put to a shareholder vote as soon as practical. Some other common parameters include:

- No lower than a 20 percent trigger;

- A term of no more than three years;

- No dead-hand, slow-hand, no-hand, or similar feature that limits the ability of a future board to redeem the pill; and

- A shareholder redemption feature such as a “qualified offer clause” which states that if a board refuses to redeem the pill 90 days after a qualifying offer is announced, 10 percent of the shares may call a special meeting or seek a written consent to vote on rescinding the pill.

NOL Poison Pills are treated slightly differently by institutions and proxy advisors. Under section 382 of the Internal Revenue Code, net operating losses (NOLs) can usually be carried forward for up to 20 years to offset a company’s future taxable income but will become impaired if a change-of-ownership occurs. In order to protect these assets, a company may install an NOL poison pill with a trigger threshold below five percent. In particular, ISS and Glass Lewis evaluate these protective instruments on a case-by-case basis, taking into account several factors, including the value of the NOLs, the likelihood of a change of ownership, whether the term of the plan is limited in duration or has a “sunset” provision, and whether the pill is subject to periodic review or shareholder ratification.

Other takeover defenses closely examined by activist investors (not previously mentioned) include:

- Supermajority vote requirements to remove directors or approve mergers;

- “Poison Put” provisions in a company’s debt instrument requiring loans to be repaid in the event of a change-of-control;

- The ability for a board to issue preferred stock to a “friendly” investor;

- The existence of a dual-class stock structure and differing shareholder voting privileges

Director Overboarding The concept of overboarding, which refers to a director who sits on too many boards, was addressed in ISS’s 2015 policy survey, which queried investors and companies to ascertain their view on acceptable limits for the number of total boards held.

As a result of the survey, in November 2015, ISS adopted the following changes to its US policy:

- Vote against or withhold from individual directors who sit on more than five public company boards (the former policy affords for individuals to sit on six public company boards); and

- Vote against or withhold from individuals who are CEOs of public companies who sit on more than two public company boards other than their own.

Glass Lewis, on the other hand, reduced the acceptable number of total corporate board positions to five from six for directors and from three outside boards to two for executive officers.

The change, however, wasn’t positively received by all corporate governance professionals. In a letter to ISS, The Society of Corporate Secretaries & Governance Professionals advocated that ISS not change its overboarding policy, stating that, “Imposing arbitrary limits on board service unnecessarily limits the pool of director candidates and increases the difficulty of finding and retaining the most effective directors.”

Additional Corporate Governance Analysis Other important corporate governance provisions that are usually included in a company’s bylaws, public disclosures, and other governance documents worthy of an activist’s comprehensive understanding include the following:

- Advance notice provisions which determine how and when an investor can submit proposals, including director nomination proposals, for shareholders to consider at a company’s annual meeting;

- Executive compensation ties to performance and problematic pay practices— an increasingly important component of effective board governance;

- Share ownership and the expectation that executives and directors acquire sufficient personal stock ownership has become the norm for public companies and provide comfort to investors that a company’s leadership has aligned themselves with other shareholders in becoming beneficiaries of improved share value;

- Company policies regarding board-shareholder communications;

- The impact of employment contracts and golden parachutes in a change of control;

- The existence of an employee benefit plan and its voting authority; and

- Cumulative voting rights.

After understanding the implications associated with a target company’s legal and governance structure, activists will then undergo an in-depth analysis of a company’s shareholder base.

Analyze the Shareholder Base

Obtaining a clear understanding of how company shareholders will vote in a contested election is one of the most important components of any activist campaign. It dictates an activist investor’s approach to buying securities, its demands for change, and its shareholder communications strategy. Following are some typical considerations of a potential target company’s existing shareholder base:

- Activists may consider the proportional ownership of institutions, retail investors, hedge funds, or “insiders” of the target.

- Since institutional shareholders are almost always the largest owner of a target company’ stock, it’s important to examine the percentage of shares held by these groups, their level of investment fatigue, voting tendencies, and underlying governance policies to help build early vote projections.

- The anticipated impact of institutional voting recommendations coming from proxy vote advisors such as ISS and Glass Lewis can be important considerations.

- The ability to build and exit a significant ownership position, taking into account daily trading volume, the amount of shares held in short positions, and potential liquidity events necessary to exit the investment can also be an important factor.

At this stage in the playbook, an activist investor determines how much stock ownership is required to promote change and begins to formulate a securities acquisition plan that may include buying stock, debt, options, or other derivative instruments.

Determine the Ownership Threshold for Change

Following a thorough examination of a company’s governance provisions and its shareholder base, an activist should have a fairly reasonable understanding of the level of ownership required to mount a successful insurgency. At this point the activist will consider a variety of ownership and regulatory issues, including:

- Public filing requirements with the SEC (activist-oriented shareholders with more than five percent ownership are required to disclose their position and their investment “intent” via a 13D filing);

- How to disclose and manage the ownership of convertible debt, options, and other derivative instruments;

- The possibility or necessity of teaming up with other shareholders, which may require additional SEC disclosure if the group owns more than five percent, as well as a contract outlining how the parties will be voting shares, negotiating settlements, communicating publicly, and sharing expenses;

- Ownership in excess of 10 percent which exposes the investor to “insider” disclosure issues, short-swing profit liabilities, and other matters that may be determined by a company’s state incorporation statutes; and

- The Hart-Scott-Rodino ownership value threshold, disclosure, and clearance process.

The Target Is Identified

With phase one of the activist investing process now complete after two to four months of research and analysis, an activist will begin to purchase the requisite number of shares necessary to successfully engage with a company’s leadership (phase two) and, if necessary, undertake a successful solicitation effort (phase three).

While not all campaigns are the same, we’ve found that the most sophisticated activists follow a predictable pattern of analysis to be successful—one that starts with the identification of a solid activist target that meets the predetermined parameters outlined in this post. With phase one of a successful activist campaign complete, the activist turns its attention to phase two—engagement with management, which usually begins with a management meeting and escalates into public discourse. Sometimes the dialogue is productive, in which case the activist’s campaign remains low-key and behind-the-scenes. Many times it does not—in which case the activist begins to contemplate phase three.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print