Lane T. Ringlee is a Managing Partner at Pay Governance LLC. This post is based on a Pay Governance publication by Mr. Ringlee, Chris Brindisi, and Peter Ringlee.

As shareholders of U.S. public companies demand more accountability for performance, Boards are under increased pressure to continue to strengthen the P4P linkage of their incentive compensation plans. In a 2013 survey of Compensation Committee members co-sponsored by the NYSE, Conference Board, and Pay Governance, [1] the top 3 “challenges” that Committees stated they were facing involved incentive pay and performance goal setting. Specific challenges noted in the survey included:

- determining appropriate incentive pay levels (62%);

- balancing P4P with retention (57%); and

- ensuring the rigorous nature of incentive plans (57%).

Although the survey is a few years old, our experience tells us this remains a hot issue in Boardrooms today. Setting annual and long-term performance targets continues to be challenging, particularly given uncertainties in the market related to interest rates, commodity prices, foreign exchange, and the many other underlying assumptions involved in setting a business plan and incentive goals.

Key Takeaways

- Setting reasonably attainable annual and long-term incentive targets has become increasingly difficult for companies due largely to external factors.

- For similar reasons, companies have increasingly turned to performance ranges for communicating external earnings guidance to shareholders.

- As a result of the externalities influencing budgeting and forecasting accuracy, companies are considering the use of a “target range” rather than a specific “point” target for incentive plans.

- Target ranges provide an opportunity to earn/fund target incentives if performance is between the lower and upper range boundaries.

- Target ranges may provide additional benefits: alignment with external guidance structures, reduced risk for adverse performance behaviors around target, reduced impact of externalities on target awards/funding achievement, and greater pay/performance risk outside of the range (for adverse outcomes or exceptional performance).

- The width of a target range needs to be carefully tailored to the chosen metric.

The challenge for Boards in setting goals is underscored by the difficulty management experiences in establishing performance expectations for shareholders and the research analyst community. In their research on management earnings forecasts at companies covered by the First Call Company Issued Guidelines database, Ciconte, Kirk, and Tucker document the increased prevalence of earnings range estimates with upper and lower bounds and the decreased use of earnings point forecasts. [2] Point forecasts are synonymous with discrete performance targets for incentive compensation. But as Ciconte et al demonstrate, the use of point forecasts has decreased to 11.3% of cases in 2010 while prevalence of range forecasts has increased to 87.5%; in 1996, the use of point forecasts occurred in 30.0% of cases in contrast to range forecasts used by 38.2% of companies.

Given all these unknowns and the clear trend toward using ranges for financial performance guidance to shareholders, it is not surprising we find companies looking for alternative approaches to traditional performance goal setting. A number of companies have opted to establish a “target range” in their incentive plans to acknowledge the imperfections in setting a single fixed target. This is consistent with the practice of providing range guidance to the financial community.

What is a “target range?”

A “target range” establishes a reasonable range around the business plan to pay or fund incentive compensation at the target award level rather than establishing a single, fixed performance target. It is, in essence, a compromise by which both shareholders and management give up some gains around a reasonable set of outcomes and acknowledge the imperfection in establishing performance expectations to shareholders, analysts, and employees.

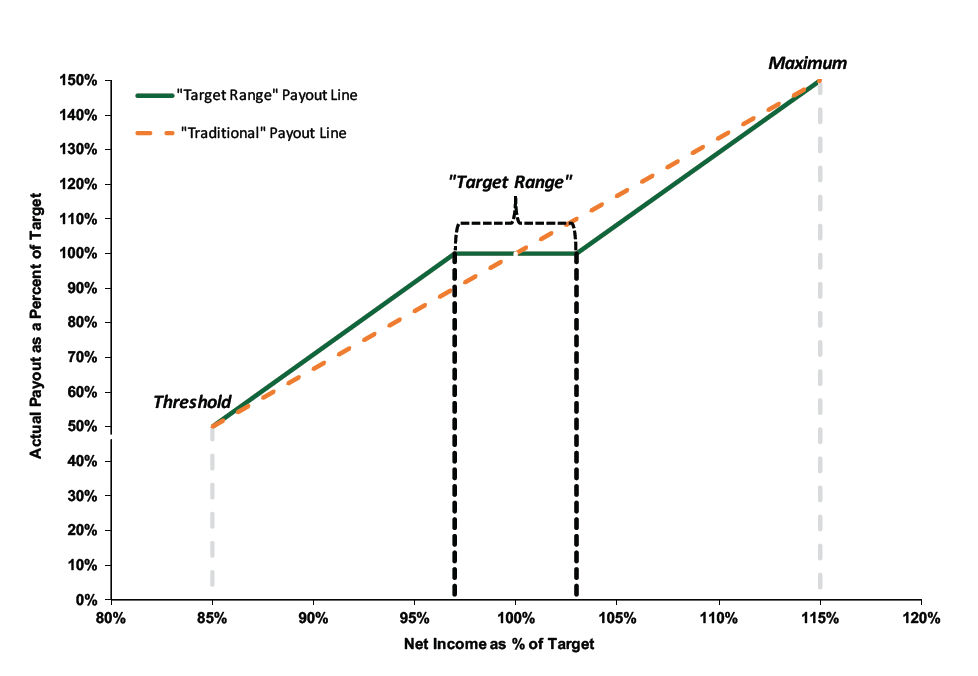

For example, a company could establish a range around a target net income goal of ±3%, which implies that the slope of the incentive payout line is flat between 97% and 103% of the target goal. This results in the same payout (100% of target) for all outcomes across that segment of the curve (see “Target Range” bracket in graph below). Net income performance below the lower boundary of the target range results in declining award payouts to the threshold level of performance, while performance above the upper boundary of the range results in incrementally higher awards up to the maximum payout. The overall performance range (upper and lower performance boundaries at which maximum and threshold incentive awards are paid) will likely vary depending upon the confidence/uncertainty level associated with the performance metric. The use of the “target range” increases the pay/performance slope beyond the lower and upper range boundaries if no adjustments are made to the threshold and maximum performance levels.

Market Practices

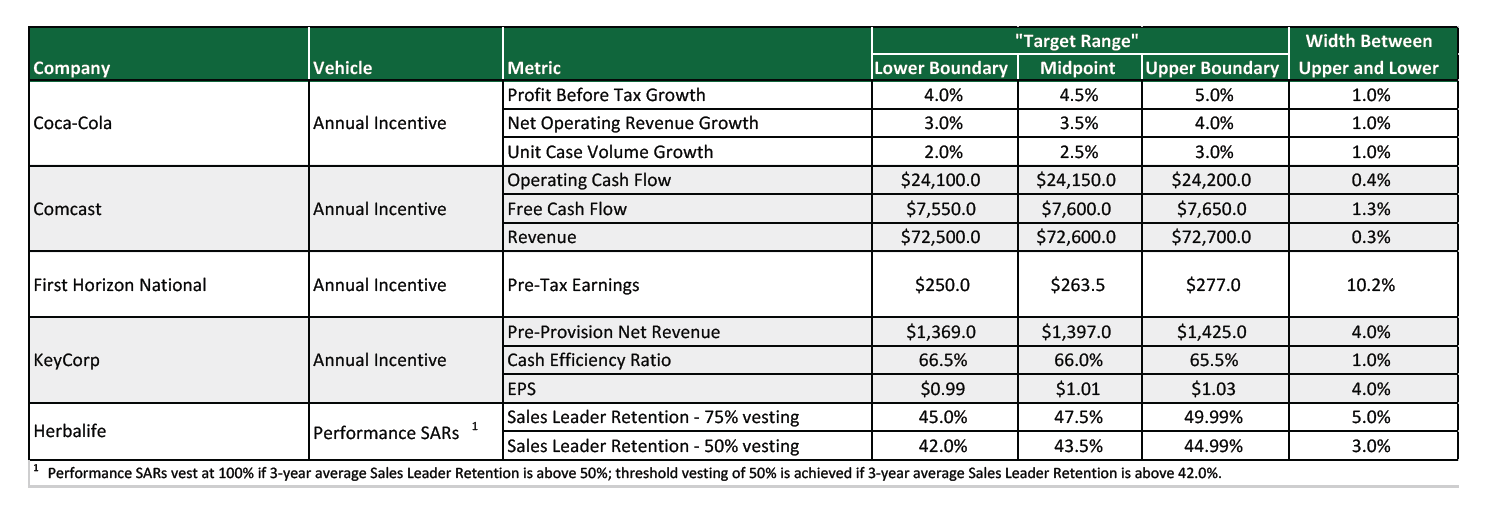

Although target ranges are not yet widely used in the market, we are finding more companies discussing the benefits of this approach every year. Practices vary by company, but generally reflect a range of 1% to 5% from the lower to upper boundary in the range.

Companies disclosing a “target range” in their 2016 proxy statement include those in the financial, media, and consumer products industries. A few specific examples are presented in the table below:

Setting the “Target Range”

In most cases, the “target range” in incentive plans is relatively narrow, reflecting the intention to provide a reasonable range for achievement (0.5% to 2.0%) without replacing the full performance range (80% to 120%). Items to consider when establishing the width of a “target range” should include:

- Is it consistent with the guidance you are providing to shareholders for similar performance metrics?

- What is the appropriate width of the boundaries (number of standard deviations) to achieve a 70% to 80% probability of achievement?

- Is the range still acceptable on an absolute dollar basis? Depending on the metric, a ±5% spread may be too wide or too narrow.

The “target range” is typically employed to give management and the Compensation Committee a reasonable margin for error when setting targets without significantly increasing the probability of hitting or missing the targets.

Considerations

The “target range” can provide some relief in the painstaking process of establishing incentive plan targets; however, there are considerations that should be understood prior to adopting this approach:

| Potential Negative Issues | Potential Benefits |

|---|---|

| Potential to reduce motivation for incremental performance—A “target range” provides for lower payouts for exceeding the business plan and higher payouts for falling below the business plan within the established range. This has the potential to reduce the motivation to produce incremental performance within the range. | Alignment with external guidance—As noted above, there is an increasing trend to issue earnings and performance guidance in a range rather than a single point. The use of a target range for incentive compensation may improve the alignment of internal expectations with external communications. |

| Increased risk due to higher required performance for upside—Since it now requires a higher level of performance to exceed the 100% payout level, executives could be motivated into taking additional risks to achieve above‐target payouts. | Reduced risk for incremental performance around target—Achieving target performance or higher is an important accomplishment for competitive compensation opportunities and a symbolic achievement for the organization. Falling slightly short of performance targets late in the measurement period can encourage behaviors that may result in poor business decisions. Establishing a range of performance outcomes takes some of the “risk around meeting budget” off the table. |

| Requires additional communication—Participants will need to understand the “quid pro quo” inherent in the design to ensure they do not view this adjustment as a takeaway. | Influence of external factors—While Compensation Committees may adjust results within parameters permissible by IRC § 162(m) (if applicable), a target range may implicitly include the impact of certain external factors—negating any end-of-year adjustments or management requests for exclusions or inclusions. |

Conclusion

The “target range” concept can be a useful feature to increase flexibility in the plan design, recognize the volatility of potential results, and understand the numerous assumptions involved in creating the business plan while maintaining compliance with IRC § 162(m) deductibility.

Endnotes

1NYSE Governance Services. “Executive Compensation: A 2013 Opinion Survey of Compensation Committee Members.” Pay Governance. 2013. http://paygovernance.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Exec-Comp-White-Paper-B-110413-final.pdf.(go back)

2William Ciconte III, et al. “Does the midpoint of range earnings forecasts represent managers’ expectations?” Review of Accounting Studies. November 24, 2013. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11142-013-9259-2.(go back)

Print

Print