Gary Smith is a Partner and Ramona Tudorancea is a Corporate/M&A Specialist at Loeb Smith. This post is based on a Loeb Smith publication by Mr. Smith and Ms. Tudorancea.

The Cayman Islands (Cayman) has been the leading offshore jurisdiction for merger and acquisition (M&A) activity over the last two (2) years. In 2015, Cayman-incorporated companies were the target of 863 transactions worth a combined value of USD116.41bn. The value was more than twice the amount of the British Virgin Islands with USD49.62bn (with 387 M&A transactions) and well in excess of Bermuda with 498 M&A transactions with a combined value of USD67.57bn.

In 2016, Cayman-incorporated companies again led the way in terms of offshore M&A activity and were the target of transactions worth a combined USD68.85bn followed by the British Virgin Islands with USD41.65bn and Bermuda with USD41.25bn. By way of comparison, Hong Kong incorporated companies were the target of transactions worth a combined USD33.19bn in 2016.

With Cayman-incorporated companies becoming the target for such a large proportion of offshore M&A activity, this publication aims to showcase some recent trends resulting from M&A activity in the specific area of merger take-privates involving Cayman-incorporated companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges, and to discuss some related lessons which would be useful for shareholders, directors and their onshore legal advisors. While our main focus is on those transactions which actually completed in 2016, in providing our analysis on recent trends, we also reviewed M&A transactions that were either aborted or are still ongoing.

Developments of the trend for using Cayman companies for IPOs and merger take-privates

Starting with the 1990’s, many Chinese companies chose to list on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the Nasdaq Stock Market (NASDAQ) to gain, among other things, access to capital from U.S. investors and stature and credibility in an increasing global world. In or around 2011 and 2012, this trend changed. While U.S. listings remained attractive for Chinese companies, the cost of complying with reporting standards continued to increase. Additionally, a lack of comprehension by U.S. investors of the corporate structures being utilised by these companies and of the underlying business environment in China led to lower market valuations for these Chinese companies.

This opened the door for arbitrage opportunities. A Chinese company which was listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ but which had a stock market value lower than its intrinsic value would be taken private and de-listed with help from private equity (PE) sponsors and either (i) continue to be privately held and later sold to a strategic or a financial buyer or (ii) re-listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange or the Singapore Stock Exchange for a better pricing. A wave of merger take-private transactions followed and this trend remains strong to date, despite speculation of a potential clampdown on re-listing by Chinese securities regulators.

Since 2010, the Cayman Islands statutory merger regime (the “Cayman Merger Law”) has offered a more streamlined and efficient offshore alternative to the onshore merger law regimes (e.g. in New York and Delaware). The popularity of the Cayman Islands for merger take-privates further increased when in 2011 the shareholder voting threshold for approving a merger was reduced to a special shareholder resolution requiring only two-thirds of the votes cast.

As a result, no fewer than 14 Chinese companies previously listed on NYSE or NASDAQ, half of which operate in the TMT/Internet industries, completed their take-private process in 2016 by using the Cayman Merger Law.

The Nuts and Bolts of the Cayman Islands Merger Regime

The Cayman Merger Law is attractive for both companies and investors, due to the process being relatively straightforward and simpler than either a takeover offer (tender offer) under section 88 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law or a court-approved scheme of arrangement under section 86 or 87 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law.

- Forming MergerCo. The most straightforward structure used for a merger take-private is that a new company (“MergerCo”) is formed in the Cayman Islands by the investors adhering to the takeover group (often involving the founders/managers of the listed company, its parent and/or several private equity (PE) investors acting as sponsors for the purposes of the take-private transaction) (the “Buyout Group”) to take on finance and to be ultimately merged with the company which is the target of the take-private (“Target”).

- Take-Private Offer. After obtaining legal and financial advice, the Buyout Group agrees on the terms of the proposed merger take-private and the consideration which would be offered to the shareholders of the Target and makes an offer to the Board of the Target (the “Initial Take-Private Offer”). Since most of the take-private transactions are initiated by or with involvement of the management or certain shareholders represented at Board level, the merger process requires that a special committee formed of independent directors (the “Special Committee”) be designated to review the take-private offer and negotiate on behalf of the Target with the Buyout Group. This is both to ensure that the Board is in compliance with the fiduciary duties it owes the Target, and to avoid any accusation of self-dealing.

- Negotiations. The Special Committee reviews and negotiates the offer with the help of its own independent legal and financial advice, which may lengthen the process. Overall, the typical mission of the Special Committee is to: (i) investigate and evaluate the Initial Take-Private Offer, (ii) discuss and negotiate any terms of the merger agreement (the “Merger Agreement”), (iii) explore and pursue any alternatives to the Initial Take-Private Offer as the Special Committee deems appropriate, including maintaining the public listing of Target or finding an alternative buyer, (iv) negotiate definitive agreements with respect to the take-private or any other transaction, and (v) report to the Board the recommendations and conclusions of the Special Committee with respect to the Initial Take-Private Offer.

- Board Approval. The directors of each company participating in a merger (MergerCo and Target) are required to approve the terms and conditions of the proposed merger (the “Plan of Merger”), including, among other things:

- how shares in each participating company will convert into shares in the surviving company or other property (e.g. cash payable to shareholders);

- what rights and restrictions will attach to the shares in the surviving company;

- how the Memorandum and Articles of Association of the surviving company are amended; and

- what are the amounts or benefits paid or payable to any director consequent upon the merger.

- Shareholder Approval. For each constituent company (MergerCo and Target), the Plan of Merger is required to be authorized by a special resolution of the shareholders who have the right to receive notice of, attend and vote at the general shareholders’ meeting (“EGM”), voting as one class with at least two-thirds majority.

- Consents. Each participating company must also obtain the consent of (i) each creditor holding a fixed or floating security interest, and (ii) any other relevant consents or filings with relevant regulatory authorities, such as the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority or authorities in the overseas jurisdiction where the Target is registered and/or operates.

- Filing and Registration. After obtaining all necessary authorizations and consents, the Plan of Merger is required to be signed by a director on behalf of each participating company and filed with the Cayman Islands Registrar of Companies, who will register the Plan of Merger and issue a certificate of merger.

- Effective Date. The merger will be effective on the date that the Plan of Merger is registered by the Registrar of Companies unless the Plan of Merger provides for a later specified date or event. Upon the effective date, all rights and assets of each of the participating companies shall immediately vest in the surviving company and, subject to any specific arrangements, the surviving company shall inherit all assets and liabilities of each of the participating companies (MergerCo and Target).

- Shareholder Dissent. Any shareholder of a company participating in the merger is entitled to payment of fair value of its shares upon dissenting from the merger under Section 238 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law. Fair value can either be agreed between the parties or determined by the Cayman Court.

Looking Closer at the 2016 Take-Privates:

A review of the merger take-privates of Chinese companies completed in 2016 using the Cayman Merger Law shows some consistent trends with respect to financing, length of the merger process, and valuation methods and negotiations with the Special Committee.

1. Financing: Cash, Equity or Debt

In approximately 50% of the reported merger take-privates of Chinese companies completed in 2016 using the Cayman Merger Law, the Buyout Group paid for the merger consideration either with available cash of the Target or with equity financing provided by the Buyout Group:

Over 35% of deals were financed by a combination of cash, equity and debt financing. This usually translated into the negotiation and execution, at the same time as the Merger Agreement, of several commitment letters related to:

- Equity Commitments: the investors adhering to the Buyout Group execute an Equity Commitment Letterundertaking to finance the transaction, subject to completion of the merger and any regulatory approvals. They often also provide guarantees for any costs and expenses and termination fees in case the merger is not completed. Within the Buyout Group, relations between the various parties are governed by an interim Investors’ Agreement or a Consortium Agreement, negotiated prior to finalizing the merger terms.

- Term Facilities: depending on the Target and the structure of the deal, a large portion of the debt financing needed for the merger will come from one or several banks, through a syndicated lending facility. The long term loan would be usually repaid by cash generated by the Target and guaranteed by the Target and its assets. Usual guarantees may include a pledge of shares, a debenture on all surviving company’s assets, mortgages on real estate assets and other security. As there is no prohibition on financial assistance under Cayman Islands law, a company may fund or guarantee the acquisition of its own shares, as long as the transaction taken as a whole is deemed by the Board of Directors as being in the best interest of the company.

- Bridge Facilities: depending on the Target and the structure of the deal, a portion of the financing needed for the merger may come from certain short term lending by a bank or an investor, without security, to be repaid shortly after the completion of the merger.

2. Length of the Merger Process: Negotiating with the Special Committee

In most of the merger take-privates of Chinese companies completed in 2016 using the Cayman Merger Law, the Special Committee retained independent legal advice (US counsel as well as Cayman Islands counsel), as well as independent financial advice. In some transactions, the Special Committee also actively researched alternative options or considered the possibility that the Target remain listed. One of the key issues generally discussed was whether the cash available in the Target or its subsidiaries may be used for payment of the merger consideration. Also, in certain cases, after consulting with its advisors, the Special Committee asked for:

- guarantees, equity commitment letters and debt financing documents to be provided by the Buyout Group;

- the merger to be approved by a majority of the shareholders that are unaffiliated with the Buyout Group (i.e., a “majority of minority” provision);

- “go-shop” and “fiduciary out” clauses; etc.

Overall, the discussions between the Buyout Group and the Special Committee, up to the final Board approval and the signing of the Merger Agreement, lasted on average 3-9 months, with a third of the transactions taking almost a year to negotiate:

The entire take-private process, from the Initial Take-Private Offer and up to the EGM approval (but not including the post-EGM filings and the de-listing of the company from NASDAQ or NYSE), lasted on average 6-12 months, with about a third of the transactions taking even longer to complete.

For smaller deals (<USD50 million), which were mostly 100% equity-financed or financed using available cash of the Target or its parent, the merger process from the Initial Take-Private Offer and up to the EGM approval typically lasted between 6 and 9 months. On the contrary, larger deals (> USD300 million), which were financed by a combination of cash, equity and debt financing, required approx. 11-20 months to complete.

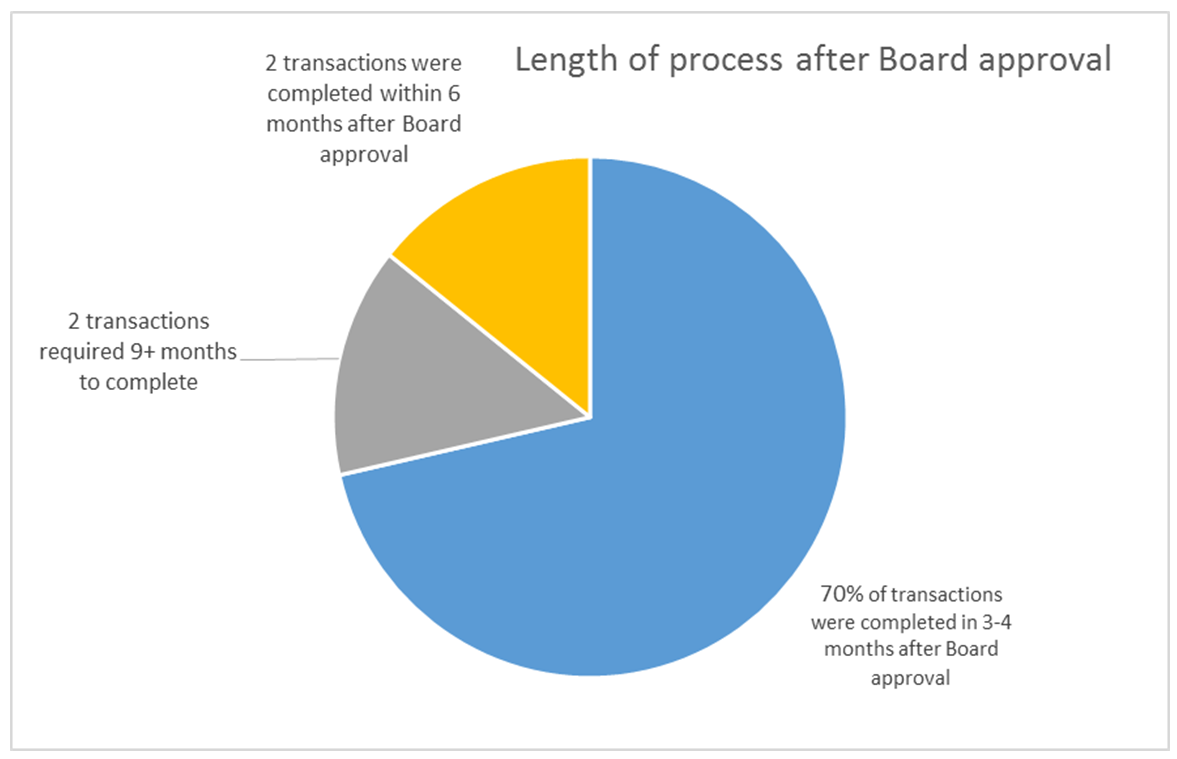

Overall, the Cayman Merger Law facilitated a straightforward and speedy process, with 70% of the mergers being completed (i.e. approved by the EGM) within 3-4 months of Board approval of the Initial Take-Private Offer or of a revised offer:

3. What Value? Valuation methods

All of the merger take-privates of Chinese companies listed on NYSE or NASDAQ which were completed in 2016 using the Cayman Merger Law offered shareholders a merger consideration substantially higher than the average pre-merger trading price (ranging from 17-49% for NASDAQ companies and 2-95% for NYSE companies, compared to the company’s trading price prior to the “going private” proposal announcement). However, the due diligence carried out by the financial advisors and the valuation methods used largely differed for each company. In addition to reviewing the accounts and financial projections provided by management, the financial advisors to the Special Committee carried out a number of investigations, based on:

- a discounted cashflow analysis on the financial projections for a period of 4-5 years;

- a review of the projections of certain public companies presenting the most similarities (between 4 and 16 companies, including Chinese companies, were reviewed to determine the typical EBITDA multiples);

- an analysis of certain M&A deals in the industry for similar companies; and

- a “premium paid” analysis compared to trading history.

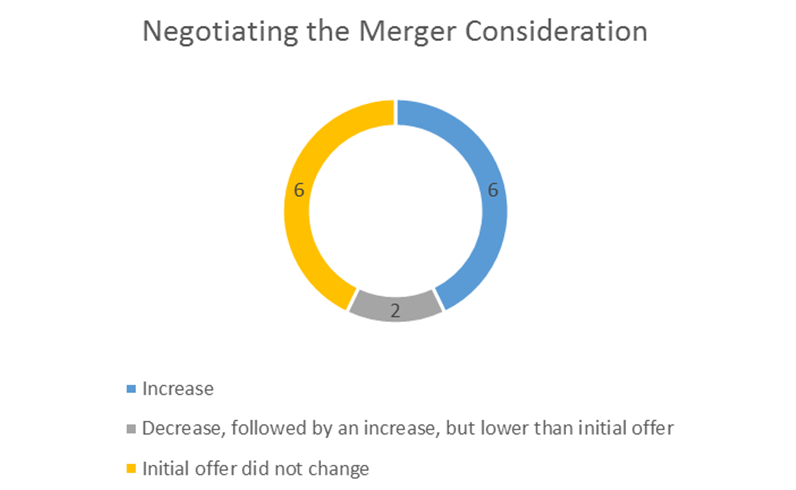

During negotiations, in six (6) cases the Special Committee was able to obtain a better price per share compared to the Initial Take-Private Offer and in two (2) cases to improve upon a reduced revised offer. In general, this required the Special Committee to compromise on certain amendments of the Merger Agreement that they had previously requested, such as the “majority of minority” provision referred to above.

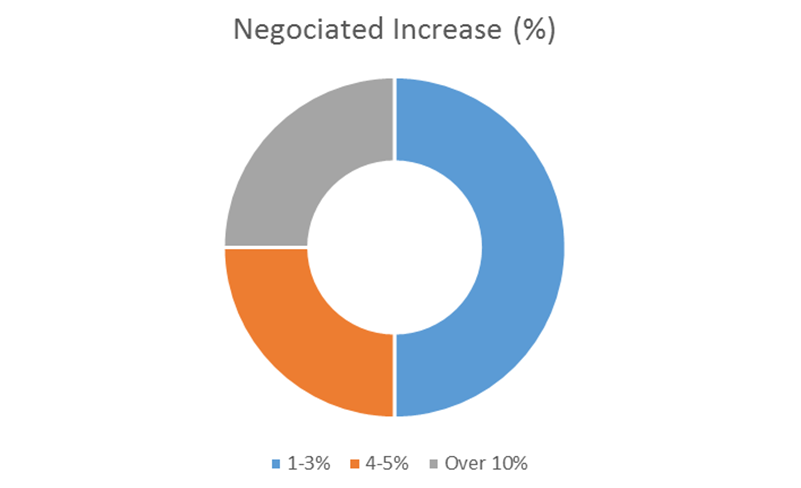

In approximately 50% of these cases, the Special Committee was only able to obtain a small increase (between 1-3%) of the merger consideration. The biggest increase was noted in a merger where the initial offer fell significantly below the valuation range finally provided by the financial advisors. In two (2) cases, the Initial Take-Private Offer price was found higher than the valuation range provided by the financial advisors and the merger consideration was not increased or was very slightly increased. It is worth noting that in some of these merger take-private deals, dissenting minority shareholders who dissented under the Cayman Merger Law may have negotiated much larger increases compared to the Initial Take-Private Offer price for themselves, but of course there are no published statistics on these negotiated settlements.

Top 5 Lessons for the Buyout Group from the 2016 Take-Privates:

- Do Your Homework: Learn all about the merger process, likely requests from the Special Committee, typical clauses included in a Merger Agreement and what is standard market practice. For example, in several of the 2016 merger take-privates the Special Committee requested the inclusion in the Merger Agreement of a “majority of minority” provision (i.e. a clause stating that, to be effective, the merger needed to be approved by a majority of the shareholders unaffiliated with the Buyout Group). This clause, however, deviates significantly from the majority requirements of the Cayman Islands Companies Law (i.e., a majority of 2/3 of the votes cast) and is not market practice.

- State Your Intentions: The Special Committee will be less likely to request a “go-shop” period or actively look for alternative buyers if the Buyout Group, in the initial non-binding offer, clearly states, among things, that they do not intend to sell their stake in the company to a third party. Actively looking for alternatives increases the risks of significantly disrupting the operations of the Target and that confidential information will leak. It also may increase the volatility of the Target’s trading price on the stock exchange and create instability among the Target’s employees.

- Let The Figures Speak: In a go-private transaction, figures and financial projections are supremely important. For example, instead of speaking about the “burden of compliance”, it is easier to show that it will be in the best interest of the Target to be privately held if the cost of compliance is well documented (between USD 1.1 million and USD 2.7 million for certain companies that completed their take-private process in 2016).

- Be Conservative: If the initial offer price is too high, the Buyout Group will need to submit and defend a revised offer with a lower merger consideration, which will create distrust among the members of the Special Committee and lengthen the negotiations. For the 2016 take-privates, this happened twice, and negotiations with the Special Committee lasted almost a year in each case. In addition, in several transactions the Special Committee agreed to drop amendments to the Merger Agreement in exchange for a modest increase in the offering price (1-3%), which a conservative initial offer allowed to happen.

- Negotiate Your Termination Fees: Take-private deals are expensive projects. In over 40% of the reported deals completed in 2016, the Company agreed to pay to the Buyout Group termination fees ranging from 1 to 10 million USD if the merger was not completed or was threatened by a competing bid or a change in recommendation by the Special Committee or the Board or a breach of the representations and warranties.

Top 5 Lessons for the Minority Shareholders from the 2016 Take-Privates:

- Monitor Your Investment: Shareholders need to maintain good communicative channels with their brokers, custodians, or nominees (shareholders of record) in order to be immediately informed of the Target receiving a take-private offer and any public filings and announcements. This will ensure that the minority shareholders have more time to become acquainted with the Cayman Merger Law and the merger process in general, to get legal advice from Cayman counsel as well as financial advice, and to assess the offer and formulate their strategy to extract a “fair value” for their shares.

- Raise Your Concerns: Early involvement by dissenting minority shareholders, through joining in with activist shareholders, writing through legal counsel to the Board or the Special Committee, or publicly communicating to the Target’s shareholders through effective media channels, will ensure that any concerns they have about the proposed merger being in the best interest of the Target, about the merger consideration not being adequate, about the financing structure – especially if the Target is helping finance the transaction, or about the Special Committee being in breach of its fiduciary duties, are raised sufficiently early and especially before the Target enters into the Merger Agreement.

- Decide Your Strategy: Dissenting minority shareholders have little negotiation leverage by themselves, but have several legal remedies available to them under the Cayman Islands Companies Law. Although requests for the Cayman Court to determine “fair value” of the shares of all dissenting shareholders under Section 238 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law are very common, minority shareholders may want to take a look at other remedies available to them prior to the EGM, including the possibility to file for an injunction to block the merger.

- Make An Alternative Offer: Some activist shareholders may initiate a counter-offer to the Initial Take-Private Offer or look for an alternative buyer which would offer a higher price per share. The Special Committee is bound by its fiduciary duties to take into consideration and to obtain independent legal and financial advice on all such alternative offers received. However, a competing bid will be reviewed by the Special Committee taking into account equity commitments and other financing available, and may be disregarded, after a certain time, if no progress with respect to such commitments and financing is made.

- Protect Your Rights: Under the Cayman Merger Law, shareholders who elect to dissent from the merger have the right to receive payment of the “fair value” of their shares if the merger is consummated, but only if they deliver to the Target, before the EGM vote, a written objection (and then comply with all procedures and requirements of Section 238 of the Cayman Islands Companies Law). However, exercising dissenter’s rights is more complicated if the Target has issued American depositary shares (“ADSs”), as ADS holders do not have the right to exercise dissenters’ rights to receive payment of the “fair value” of shares underlying their ADS. To exercise dissenters’ rights, an ADS holder must surrender the ADSs to the depositary for delivery of shares, pay the fees required for the cancellation of the ADSs, and become registered in the Target’s register of members prior to the close of business in the Cayman Islands on the record date for voting shares at the EGM, all in compliance with instructions provided by the Target in the EGM proxy materials provided prior to the EGM vote. Any brokers, banks and other nominees will therefore need to be instructed in this respect.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print