Nick Dawson is Co-Founder & Managing Director at Proxy Insight. This post is based on a Proxy Insight publication. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes: Paying for Long-Term Performance by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

Long-Term Incentive Plans (LTIPs) seem to have become the latest focus point for shareholder anger over executive compensation. Most recently, a group of MPs called on the U.K. Government to ban LTIPs from next year, claiming that they create “perverse” incentives and encourage short-term decisions.

LTIPs usually constitute the largest element of executive pay, and are typically three years in length. Around 90% of FTSE 100 companies used LTIPs in 2013, up from 30% in the mid-1990s. Over the same period, the average LTIP payout to a FTSE 100 lead executive increased from 40% of pay to more than 200%.

The MPs suggested that LTIPs should be replaced with simpler deferred stock options. These would award senior executives with shares that they would only be able to cash in years later, perhaps after retirement. Given their uncertain future, we have asked some expert compensation consultants for their commentary on LTIPs.

Matt Higgins from FIT Remuneration Consultants cautioned against an outright ban, saying: “we struggle with the inconsistency in respect of the Select Committee agreeing that one size does not fit all yet recommending that all listed companies should drop traditional long-term incentive plans. In our view, whilst restricted stock may be a sensible approach to paying executive directors in some companies, lower fixed pay and leveraged incentives may be much more in line with corporate goals and organisational culture in others, such as smaller growth companies.”

LTIPs have grown in complexity over the years, with many including “inappropriate” measures of success such as industry averages and other factors outside the control of executives. That being said, Barbara Seta, from hkp/// group, argues that “Part of the complexity of LTIPs that is frequently criticized is the very result of regulation, for example with regard to the use of performance conditions.” She went on to say: “It may well be that simpler plans—e.g. shares held over a reasonable time period—may actually be more effective.”

Mounting Opposition

Many of the U.K.’s largest businesses have received heavy criticism over the scale and timing of executive pay awards. Last year, the advertising giant WPP sparked controversy, with a discontinued scheme that awarded shares worth £42m to chief executive Sir Martin Sorrell.

Similarly, BP’s LTIP scheme last year led to an AGM defeat for chief executive Bob Dudley over his £14m award during an oil and share price slump. The company has since reduced his maximum LTIP award from seven times his salary to five.

More recently, Goldman Sachs and Hunting PLC have removed their LTIPs, with Goldman Sachs linking all equity awards given to the chief executive and chief financial officers to the company’s relative performance after a third of investors voted against its say-on-pay last year.

Even reductions in pay, like that at Goldman Sachs, can be viewed in a bad light. Cynics say they simply underline the failure of compensation committees to create a suitable long-term incentive plan in the first place.

Indeed, it is all too easy to argue that the willingness of boards to agree to pay cuts merely reinforces the idea that the compensation is not designed to align pay with performance, but rather to retain executives through excessive payouts.

A recent example of this is Credit Suisse. The bank cut executive bonuses by 40% after ISS, Glass Lewis and Ethos recommended against its compensation proposals. Glass Lewis has since said it will maintain its recommendation despite the cut, arguing that Credit Suisse’s reaction was “too little, too late.”

The Merits of LTIPs

In spite of recent bad press, there are arguments in favor of LTIPs. Proponents say they align employee and shareholder interests by putting a portion of compensation at risk as shares. Richard Belfield from Willis Towers Watson supports this view, saying: “we have found that large personal shareholdings correlate with longer CEO tenure and stronger TSR performance.” LTIPs are also designed to attract and retain superior talent who recognize that they will benefit financially from the growth they help create.

Furthermore, LTIPs are cited as a way to reinforce sustainable long-term profits rather than focusing employees on short-term goals. Higgins lends weight to this view, pointing out that “high levels of performance-related pay should only be earned for exceptional performance. As such, we would advise caution against a blanket dumping of performance shares for restricted shares in all listed companies, which, while reducing pay potential, is unlikely to improve the link between pay and performance.”

Not everybody is persuaded by these arguments. Many critics point out that the three-year duration of LTIPs is not enough to truly focus executives on a company’s long-term interest. The real ramifications of any short-term investment in equipment or human resources may not be seen until long after executives have received their payouts. This discourages investments that create long-term value for the company, as it could reduce LTIP payouts over the three-year performance period.

Critics also claim that LTIPs railroad executives towards single outcomes set by targets, rather than the complex patterns of behavior required to run a company. Indeed, many question whether executives are even responsible for reaching their targets, or whether external factors are the real drivers of company performance. Executives of ten seem to receive their payouts regardless of the actual reasons for company success or failure, LTIP opponents say.

Agnès Blust from Agnès Blust Consulting suggests that LTIPs can be made effective “by combining several performance indicators that reward for growth and top-line contributions, for earnings and bottom-line contributions and for shareholders’ return in a balanced manner rather than relying on a single performance metric that may lead executives to take short-term decisions at the expense of long-term health of the company.”

Blust also suggests that “performance objectives that are set over a period of several years should be defined relatively to market peers. By doing so, market circumstances are neutralized and the true performance of the company can be assessed and rewarded.”

LTIPs: The Data

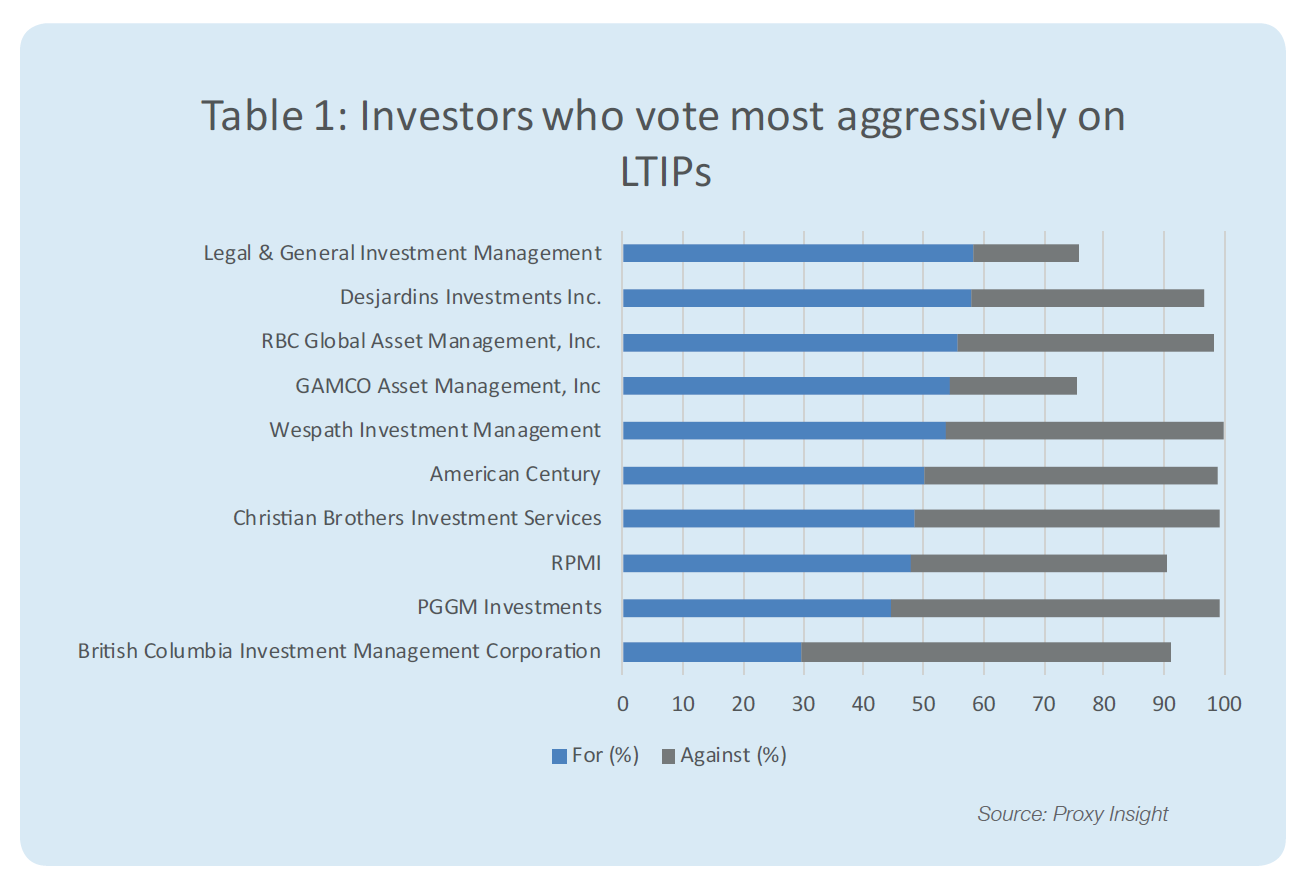

Growing shareholder unrest over LTIPs is reflected in the data with average support for their approval falling from 92.6% in 2014 to 89.7% in 2016. Of course, this still indicates a very high level of support. Even among the ten investors who vote against LTIPs most of ten, the majority still support LTIPs over 50% of the time.

The only LTIP proposal to fail in the U.K. last year was at Weir Group. This was hardly surprising, as the company’s directors were set to receive share awards where vesting did not rely performance conditions. According to Calvert’s investor rationale, this “represents a deviation from standard market practice and the Company has not provided a compelling argument to justify this approach, which remains highly unusual in the UK context.”

It is interesting to note that, while the UK government is the one keen to remove them, support for LTIPs is actually higher in the UK than the US. On average, LTIPs receive 94% support in the UK compared to 86% in the US.

Seta provides one possible explanation for the government’s actions, saying: “blaming LTIPs for excessive compensation is the easy way out of an issue that is actually quite complex. It seems that for someone with a hammer ever y thing looks like a nail.” She went on to say that “trying to regulate levels of pay by introducing further restrictions on the structure of pay is not helpful—and will not have the intended consequences.”

Belfield agrees that a ban may have unintended consequences, such as “increases to short-term incentives / fixed pay, to retain competitiveness (as seen in the banking sector where the variable pay cap resulted in higher salaries and fixed allowances).”

“It is therefore unlikely,” Belfield continues, “that the removal of LTIPs would reduce overall quantum, which as we understand it, is a key driver for this initiative. It would reduce the link between pay for performance— pay would be the same in years of good and poor performance and would generate a disconnect with the investor experience.”

Whether or not the government will accept the BEIS select committee’s hardline suggestions remains to be seen, but it looks as though LTIPs will remain a controversial topic for shareholders this proxy season.

Proxy Insight has already picked up five UK companies this year receiving greater than 10% opposition to their remuneration policy or report where LTIPs were cited in investor rationale as a reason for voting against. Most significantly, Crest Nicholson’s remuneration report attracted 58% opposition.

Print

Print