Kal Goldberg is a Partner and Head of the US capital markets and transactions group and Charles Nathan is a Senior Advisor at Finsbury LLC. This post is based on a Finsbury publication by Mr. Goldberg and Mr. Nathan.

The New Normal for Activist Investor Campaigns

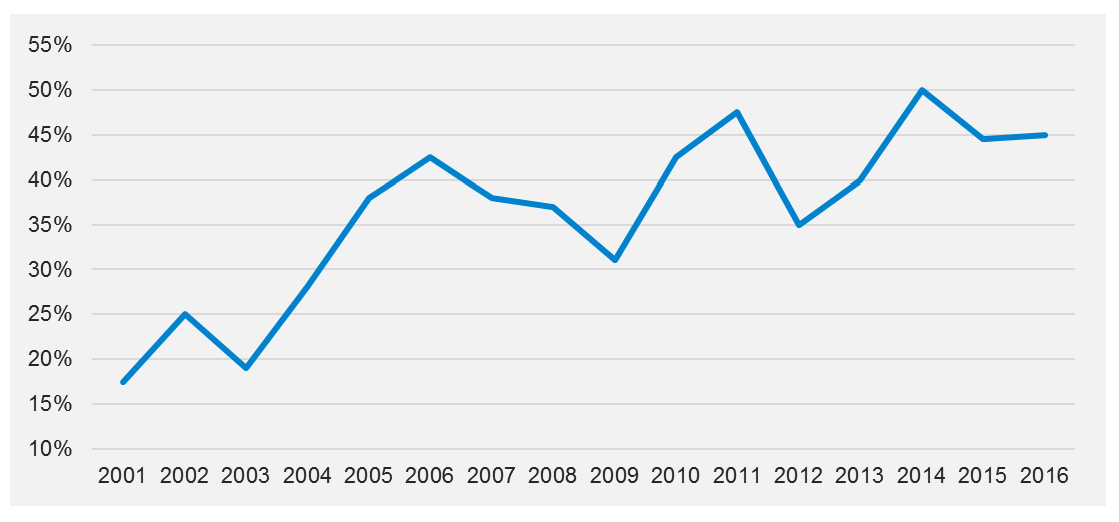

Over the past several years, the end game for activist investor campaigns has increasingly become a consensual settlement of some sort, rather than a proxy contest to “the death”. In 2016, 45 percent of activist proxy contests ended in a settlement, up from 35 percent in 2012. Looking further back, the trend becomes even starker—less than 20 percent of proxy fights in 2001 ended in settlement. The percentage of activist campaigns ending in settlements prior to initiation of a proxy contest, of course, is far higher.

Percentage of Proxy Fights Settled Instead of Fought

Source: FactSet Shark Repellent

The increase in settlements both before initiation of a proxy contest, as well as after, has been driven by a number of factors. For one, proxy fights are distracting and expensive—the average median cost of defending against an activist has doubled in the last five years, according to FactSet. Second, past activist successes have made even the most confident CEOs wary of engaging in all-out war with a seasoned activist investor. Such risk aversion has been compounded by the fact that the two dominant proxy advisory firms—ISS and Glass Lewis—have policies that favor an activist’s agenda, placing the burden of proof on the company and, particularly when a director short-slate is nominated, often defaulting to a posture of “what’s the harm in adding new blood to the Board?” Third, and of increasing importance, companies are pre-empting activists or constructively engaging with them before or soon after they “go public” because the companies have been contemplating some or all of the changes being advocated by the activists, making it easier to reach an early quiet settlement. This is particularly true with activists who may be willing to compromise if they see movement in the right direction. For some companies, settling with a “reasonable” activist might even be part of a defense strategy against another, more combative activist. These “reasonable” activists, who are increasingly prevalent, are trying to shed the image of short-term corporate raiders in favor of a more “constructive” approach to activism, similar to the approach followed by the late Ralph Whitworth at Relational Investors.

Whatever the reason for the increase in settlements, what really matters from a communications perspective is that even though not all settlements are the same—some come early, some come at the eleventh hour, some involve compromise, others capitulation—they all carry the same negative connotation for the target. How can settling with your aggressor ever be a “win”?

Communications Challenges of a Settlement

Activism doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game. But the media will frame it as such because stories with winners and losers are more exciting than stories about compromise. Accordingly, the greatest post-settlement communications challenge for a target company is pushing back against the media’s inclination to declare a “winner.” Doing so effectively is the best way to preserve the credibility and reputation of the Board and senior management.

Obviously, this is not easy to achieve. In the absence of a convincing positive rationale for the settlement, most institutional investors and media will assume that the company settled because it lacked confidence in its ability to win a proxy contest and thus, as a practical matter, was “defeated” by the activist.

The best way to counter this perception is to make the communications treatment of the settlement part of the negotiation. The timing, substance and rollout of a settlement announcement will significantly impact the extent to which it is perceived as a Board and senior management loss, a compromise or a “win-win,” and should, if at all possible, be agreed with the activist in advance.

Ideally, the announcement should be framed as the Board and senior management embracing the outcome reached in the settlement. If feasible, the Board and senior management should take at least partial credit for the changes, whether they be corporate governance changes or a shift in strategy, and should communicate their openness to new ideas. Of course, some activists will be more open to such an approach than others, but importantly the longer a campaign is allowed to drag on, the more difficult it will become to frame a settlement outcome as a “win-win.”

Take, for example, the different outcomes in two recent activist investments in industrial companies—Pentair and Arconic. In the former situation, the CEO of Pentair publicly welcomed Trian as a major investor. The surrounding press reports were favorable to Pentair and its CEO, and there was no perception that the company had suffered a “defeat” at the hands of an activist investor. The Arconic story, of course, was quite different, and there can be no doubt that the over-riding public perception is that the Arconic Board suffered a stinging “defeat” at the hands of Elliot.

Regaining Control of the Narrative

Settlement with an activist is rarely the end of the story. In many, if not most, cases, it is the beginning of a period—of months or even years—characterized by changes in corporate strategy, operations, capital structure and/or governance. In some cases, the activist may reemerge demanding even more far-reaching changes than those agreed to in the settlement.

The bottom line for any company that settles with an activist, is that change will become a constant, and scrutiny by investors and the media will be intense. Under such circumstances, the best way for a Board and management team to take back control, regain credibility and re-establish a positive reputation with the market (and, no less important, the company’s other constituencies) is to close the activist chapter as quickly as possible by communicating a credible long-term agenda that goes beyond the settlement. The settlement should be framed as a step towards a set of strategic objectives defined by the company, ideally without giving public credit to the activist. Trian’s recent investment in Pentair again serves as a valuable example. It was accompanied by a public campaign by the Pentair CEO emphasizing the company’s significant growth ambitions which (while supported by Trian) did not attribute either the strategy or its implementation to Trian.

Conclusion

Settling with an activist is rarely, if ever, a happy event in the life of a public company, but the negative reputational impact on the Board and senior management can be minimized by implementing an effective, proactive communications strategy from the outset.

Agreeing on the rollout and messaging of settlement communications with the activist gives the target the best chance of successfully pushing back against the perception that any sort of settlement is inherently a loss for the company. Moving on from the activist chapter as quickly as possible by communicating a credible long-term strategy that embraces change and, in the optimal case, goes beyond the settlement is by far the best way to preserve the authority and enhance the reputation of the Board and management team.

Clearly, the strategy and tactics of activist defense should not be determined solely by communications issues. But the communications implications of settlement should not be ignored, because they can have a significant impact on the Board’s and senior management‘s reputation with all of its constituencies following settlement, and therefore their ability to execute the strategy.

Print

Print