Beckwith B. Miller is a Managing Member, Gary F. Henry is Chief Executive Officer and Howard R. Sutherland is a Member of the Advisory Board at Ethics Metrics LLC. This post is based on an Ethics Metrics Publication by Mr. Miller, Mr. Henry and Mr. Sutherland.

U.S. Government Initiatives (USGIs) to “foster economic growth and vibrant financial markets through more rigorous regulatory impact analysis that addresses systemic risk and market failures, such as moral hazard and information asymmetry” [1] are failing because of a deeply ingrained industry practice and bias. Bank regulatory oversight protects the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund and the stability of the financial markets, but not investors.

This practice centers on information asymmetries permitted by federal bank regulators that classify material information, including formal enforcement actions (FEAs), internal fraud and external fraud, as confidential for regulated depository institution holding companies (DIHCs). As a result, many of the 100 largest (assets +$10 billion) DIHCs, from 2002 to the present, are able intentionally to withhold material information, including negative events that ordinarily require disclosure, from investors and the public. Disclosure of 565 FEAs, reflecting events of default in credit agreements and material contracts required to be disclosed by the SEC, led to default for 39% of these 565 DIHCs. Only 11 FEAs were issued for largest DIHCs but the default rate was 55%. The risk profiles for many of the current 100 largest DIHCs, that did not disclose a FEA, match the risk profiles of the 112 DIHCs with assets between $1 billion and $32 billion that did disclose a FEA. This information concerning the largest DIHCs was suppressed because the government could not afford the failure of any one of the largest DIHCs with the limited financial resources of the FDIC. This undisclosed material information, however, is directly relevant for evaluating the risk of default and actual defaults of large, systemically interconnected DIHCs and overall systemic risk as defined in the Dodd Frank Act, Sec 203(b) and Sec. 203(c)(4)(D): “the financial company is, or is likely to be, unable to pay its obligations (other than those subject to a bona fide dispute) in the normal course of business.”

Intentionally omitting the foregoing material information not only conceals fraud and risk factors that cause default and systemic risk, but it also qualifies as material omissions and material misstatements contributing to accounting fraud and ineffective internal controls over financial reporting. Ethics Metrics has addressed these issues in our previous posts: Federal Banks’ Permitted Concealment of Material Information and Systemic Risk, May 25, 2017, and Déjà Vu: Model Risks in the Financial Choice Act, June 25, 2017.

This selective, pro-DIHC, omission of material information is not available to small DIHCs (assets <$10 billion) because: (1) formal enforcement actions are routinely disclosed by the Federal Reserve for small DIHCs, [2] (2) internal and external fraud operational risk analysis only applies to large DIHCs, and (3) state bank regulators typically require that all formal enforcement actions be publicly disclosed.

This preferential disclosure regime for large DIHCs has created a bifurcated market in the U.S. banking industry that features:

- Apparent market stability, but a fragile stability dependent upon information asymmetries that conceal fraud and systemic risks affecting all investors in large DIHCs. Those investors include other DIHCs as counterparties, as well as central clearing organizations for OTC derivatives. The 100 largest DIHCs now own about 80% of the $16 trillion in total U.S. bank industry assets, an increase from 55% in 2005.

- Effective market discipline with transparency and market integrity for investors in small DIHCs, a market that is less than 20% of total industry assets.

Four U.S. Government Initiatives (USGIs) perpetuate these information asymmetries in 5 ways. The four USGIs are the Treasury’s Financial Plan of 6/12/17 (the Treasury Plan), [3] ongoing Dodd Frank Act Stress Tests, [4] the Financial Council on Systemic Risk (FSOC), and the Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual. These USGIs operate as follows:

(1) The Treasury Plan and FSOC simply do not address any of these ongoing information asymmetries. The Treasury Plan does cite one asymmetry called the QM patch, which relates to qualified mortgages, but entirely omits the material issues noted above.

(2) The Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual provides extensive explanations of why formal enforcement actions and related CAMELS Ratings are not allowed to be disclosed or cited by bank holding companies to the public. For the sake of brevity, the relevant insights are not included here, but please see Section 2128.05, [5] dated July 2005, and Section 4070.5, [6] dated July 2008.

(3) Dodd Frank Act Stress Tests (DFAST) intentionally withhold disclosures of internal fraud and external fraud from the public by classifying these risks as confidential information. The DFAST Instructions state, “F. Confidentiality. As these data will be collected as part of the supervisory process, they are subject to confidential treatment under exemption 8 of the Freedom of Information Act (5 U.S.C. 552(b)(8)).” [7]

(4) The USGIs are narrowly focused on one of four identified systemic risk factors, i.e., capital adequacy (DFA Sec. 203(c)(4)(B)), but omit significant metrics and disclosures that would reveal liquidity risks (DFA Sec. 203(c)(4)(D)), while purporting to evaluate threats to the stability of the U.S. financial system from large interconnected bank holding companies, as defined in Dodd-Frank §§ 111(a), 112. Further analysis on this issue is provided below.

4-A: The Treasury Plan, on page 33, indirectly defines systemic risk through its reference to “Mitigation of Systemic Risk; Dodd-Frank established the FSOC for the oversight of systemic risks.36” The references in Footnote 36, to Dodd-Frank Act §§ 111(a), 112, are helpful but one has to follow the chain of definitions in the Act to learn that FSOC has the responsibility to

“identify risks to the financial stability of the United States that could arise from the material financial distress or failure, or ongoing activities, of large, interconnected bank holding companies or nonbank financial companies, or that could arise outside the financial services marketplace.” (emphasis added)

4-B: Systemic risk threats are defined in the Dodd Frank Act, Section 203(b)(1), Systemic Risk Determination, and Sec. 203(c)(4) as one of four factors for “Danger of default or default.”

“Sec. 203(c)(4)(A) a case has been, or likely will promptly be, commenced with respect to the financial company under the Bankruptcy Code;

Sec. 203(c)(4)(B) the financial company has incurred, or is likely to incur, losses that will deplete all or substantially all of its capital, and there is no reasonable prospect for the company to avoid such depletion; (emphasis added)

Sec. 203(c)(4)(C) the assets of the financial company are, or are likely to be, less than its obligations to creditors and others; or

Sec. 203(c)(4)(D) the financial company is, or is likely to be, unable to pay its obligations (other than those subject to a bona fide dispute) in the normal course of business.” (emphasis added)

4-C: The results of the DFAST Stress Tests are focused on capital adequacy levels, as a systemic risk event under DFA Sec. 203(c)(4)(B), based on a number of adverse economic scenarios. The DFAST Stress Tests provide no metrics for potential loss of liquidity or noncore funding [8] as defined in the Bank Holding Company Performance Report for the systemic risk event of liquidity risks under DFA Sec. 203(c)(4)(D). As an indication of the materiality and magnitude of the potential systemic risks, the total equity capital of the 100 largest DIHCs is $1.9 trillion while noncore funding, which provides significant liquidity to those 100 largest DIHCs, is $4.6 trillion as of March 31, 2017. Noncore funding is a material risk in itself, as defined by the FRB in the following sections of its Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual.

4-C-1: Noncore funding consists largely of uninsured funding sources that are described as volatile funding sources [9] in Section 2080.05.1, Funding and Liquidity, of the Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual. “Noncore Funding” is the sum of time deposits with balances of $250,000 or more, deposits in foreign offices and Edge or Agreement subsidiaries, federal funds purchased and securities sold under agreements to repurchase, commercial paper, other borrowings (including mortgage indebtedness and obligations under capitalized leases), and brokered deposits less than $250,000. [10]

4-C-2: Volatile funding sources are a concern for the FRB as it states in Section 2080.05.1, “Special attention should be given to the use of overnight money since a loss of confidence in the issuing organization could lead to an immediate funding problem.” [11]

4-C-3: Risk guidelines for volatile funding sources are defined by the FRB in Section 2080.05.3 EXAMINER’S APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES IN EVALUATING LIQUIDITY AND IN FORMULATING CORRECTIVE ACTION PROGRAMS. [12]

Investors at Risk

Investors in the U.S. banking industry are not receiving full disclosure of material information relating to the overall financial, compliance and potential systemic risks of the largest DIHCs from either the USGIs or the public disclosures of the large DIHCs. Neither the USGIs nor the large DIHCs are addressing and incorporating into their public systemic risk models and assessments any of the financial and compliance risks that arise from the confidential supervisory examination process on capital, assets, management, earnings and liquidity. Nor are they disclosing any related FEAs for large insured depository institutions (IDIs) and their respective DIHCs, with the exception of 11 large DIHCs since 2002. As noted below, approximately 70 of the currently active, large DIHCs are eligible for FEAs but have not disclosed FEAs during the past 10 years.

“The market for large DIHCs is inefficient with limited transparency concerning material compliance violations of safety and soundness, 12 U.S.C. § 1818(b), source of strength, 12 C.F.R. § 225.4(a), well managed, 12 U.S.C. § 1841(o)(9)B, and internal fraud, 12 C.F.R. §217.101(b).” [13]

“Investors in many large DIHCs are thus being misled twice: first by clean audit opinions and management certifications on ICFR that gloss over undisclosed material negative information, and then by management affirmations under SOX that there are no material omissions. Research reveals that the risk profiles of many large DIHCs are identical to those of small DIHCs that did receive and disclose FEAs, concentrating the undisclosed risks in the largest and most systemically significant DIHCs.” [14]

A partial summary of relevant laws and regulations relating to potential accounting fraud is provided in the Appendix for Déjà Vu: Model Risks in the Financial Choice Act, June 25, 2017.

Potential Accounting Fraud—10 Year Statute of Limitations

For bank holding companies; violations of accounting standards can lead to severe penalties. 12 U.S.C. § 1847, Penalties states:

“Every officer, director, agent, and employee of a bank holding company shall be subject to the same penalties for false entries in any book, report, or statement of such bank holding company as are applicable to officers, directors, agents, and employees of member banks for false entries in any books, reports, or statements of member banks under section 1005 of title 18.”

Section 1005 of title 18 is a provision from the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA). Civil penalties in 12 U.S.C. § 1833a(c)(1) apply to violations including Section 1005 of title 18 and the relevant statute of limitations, in 12 U.S.C. § 1833a(g), is 10 years.

Identifying and Quantifying the Systemic Risk Exposures for DIHC Investors, including Counterparties and Global Equity Investors

Publicly available data from the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission yields helpful insights on two levels:

Level 1: 40 DIHCs with assets over $50 billion report their intra-financial system assets, liabilities and OTC derivative exposures through the Federal Reserve’s FR Y-15 Reports [15] each quarter. A summary of their total exposures as of March 31, 2017 follows:

| Total intra-financial system assets | $2,019,451,258,000 |

|---|---|

| Total intra-financial system liabilities | $2,065,224,469,000 |

| Common equity | $1,844,317,861,000 |

| Total securities outstanding | $4,489,319,115,000 |

| Noncore funding (from BHCPR) | $5,448,633,151,000 |

| Average risk-weighted assets | $6,754,964,967,000 |

| Total Assets of Insured Depository institutions (IDIs) | $12,299,702,957,000 |

| Total Assets (From FR Y-9C) | $16,480,405,257,000 |

| Total IDI Assets in U.S. Banking Industry | $16,965,782,000,000 |

| OTC derivatives cleared through a central counterparty | $107,902,875,295,000 |

| OTC derivatives settled bilaterally | $111,836,421,531,000 |

| Total notional amount of OTC derivatives | $219,739,296,827,000 |

| Total IDI assets of 40 DIHCs as % of Industry’s Total IDI Assets | 72% |

Further detail is provided in this link that features a segmentation of the 40 DIHCs by their primary IDI regulator of either state bank regulators or the OCC.

Level 2: 1,172 global equity investors that are registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) report through their 13-F quarterly filings that they own $1.4 trillion or 75% of the $1.9 trillion of publicly traded equity from the universe of 100 largest DIHCs. This group of investors is providing a significant portion of the equity capital that is featured within the FRB’s capital adequacy ratios and stress tests. Additional analysis indicates that 998 RIAs from the United States hold $1.2 trillion or 67% of the total value and another 174 RIAs from the UK (48), Canada (49), Japan (21), Germany (6), Norway (2), Switzerland (8), Netherlands (8), Australia (5), Korea (3), Sweden (7), France (5), Denmark (1), Luxembourg (1), Israel (4), Channel Islands (1), South Africa (2), New Zealand (1), Spain (1) and Belgium (1) have invested $152 billion or 8% of the total $1.9 trillion of publicly traded equity from the universe of 100 large DIHCs.

Efforts to Bring Transparency to Systemic Risks within Large Interconnected DIHCs

Efforts by the USGIs to bring transparency and identify the 4 systemic risks that can arise from the material financial distress or failure of large, interconnected DIHCs are limited to only a few resources:

- Search engine on formal enforcement actions (FEAs) by the Federal Reserve.

- Reports on failed IDIs and their DIHCs and their history of regulatory supervision.

- Relevant SEC and DOJ litigation cases.

- DFAST Stress Tests that focus on capital adequacy levels, as a systemic risk event, under DFA Sec. 203(c)(4)(B).

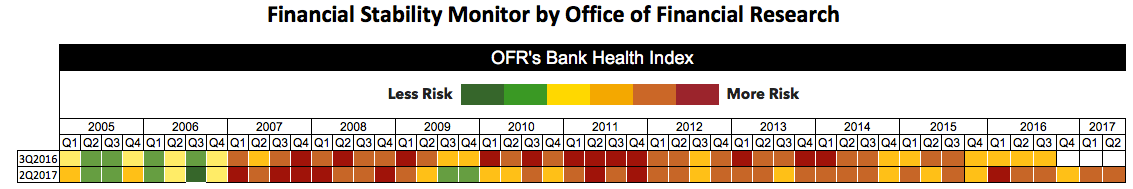

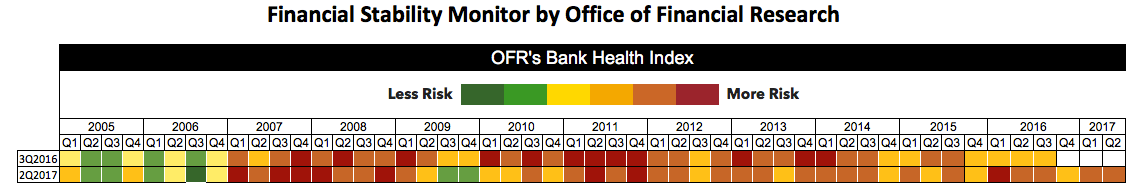

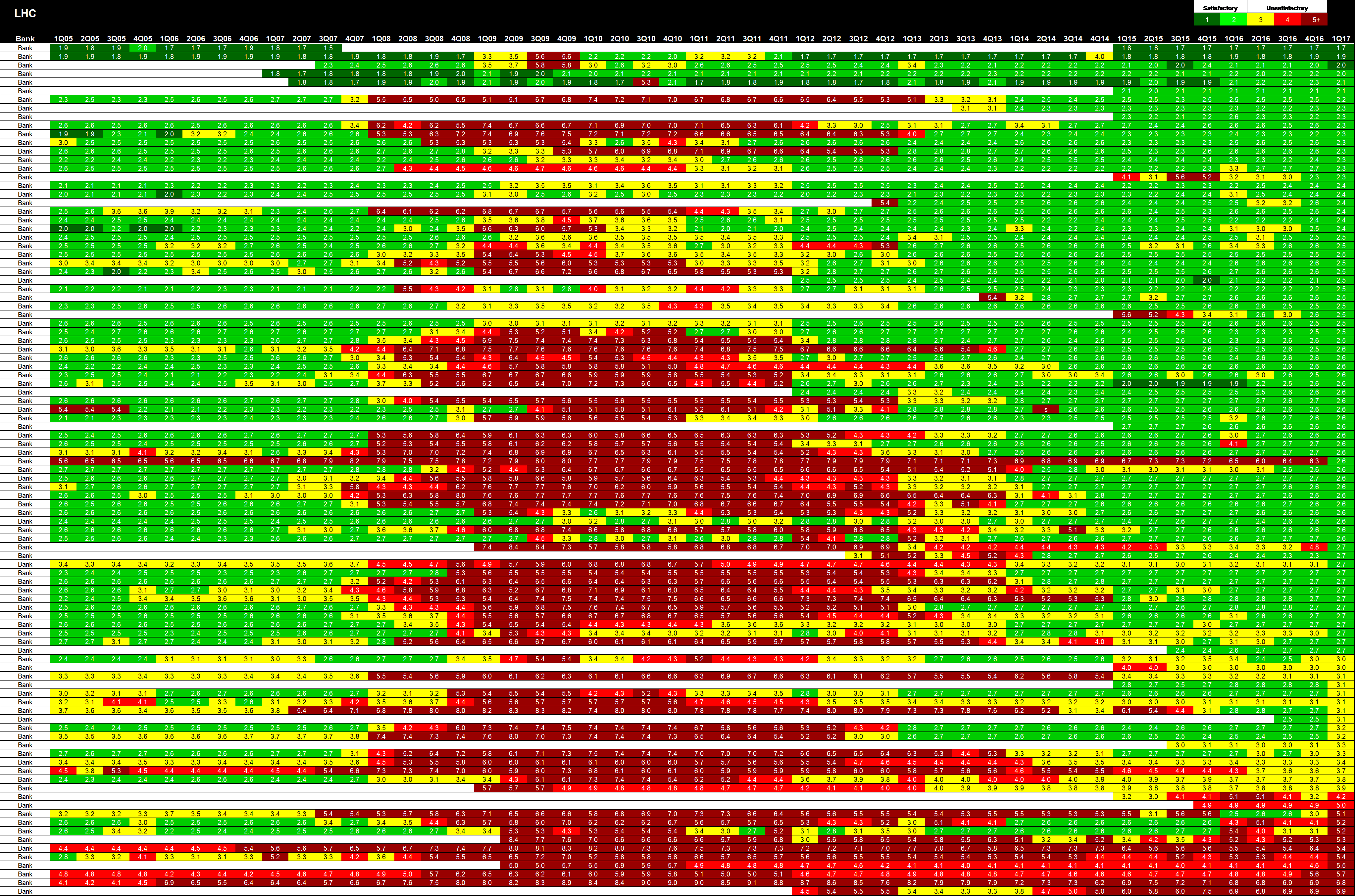

- The quarterly Bank Health Index by FSOC, from 1Q2005 to 2Q2017, is presented within its Financial Stability Monitor. [16] The top row of data was reported as of 3Q2016 while the bottom row was reported as of 2Q2017.

This chart is also featured as Chart #1 in the Addendum for the Systemic Risk Dashboard for 100 Currently Active, Large DIHCs: 1Q2005 to Present.

As a resource for DIHCs, DIHC investors and DIHC regulators, Ethics Metrics evaluated the risk profiles of the 112 largest DIHCs that disclosed FEAs from 2002 to 2017. The calculated Ethics Metrics Risk Rating for these 112 DIHCs compared closely with the issuance and termination of FEAs, validating Ethics Metrics’ ability to detect levels of non-compliance which have resulted in formal enforcement actions over the past 15 years.

Applying this same rating scale to the 100 currently active, largest DIHCs with assets over $10 billion from 1Q2005 to the present results in a:

- Quarterly Heat Map from 1Q2005 to the present for each of these DIHCs (See Chart #2 in the Addendum for the Systemic Risk Dashboard).

- Finding that only 3 of these DIHCs disclosed a FEA while at least 70 of them were eligible but did not disclose a FEA concerning possible violations of 12 U.S.C. § 1818(b)(8) on asset quality, earnings, management or liquidity.

- Finding that the risk profiles of the large DIHCs that were eligible but did not disclose an FEA are also similar to the risk profiles for all 10 litigation cases [17] brought by the SEC against smaller DIHCs and their executives that did disclose an FEA during 2002 to 2017.

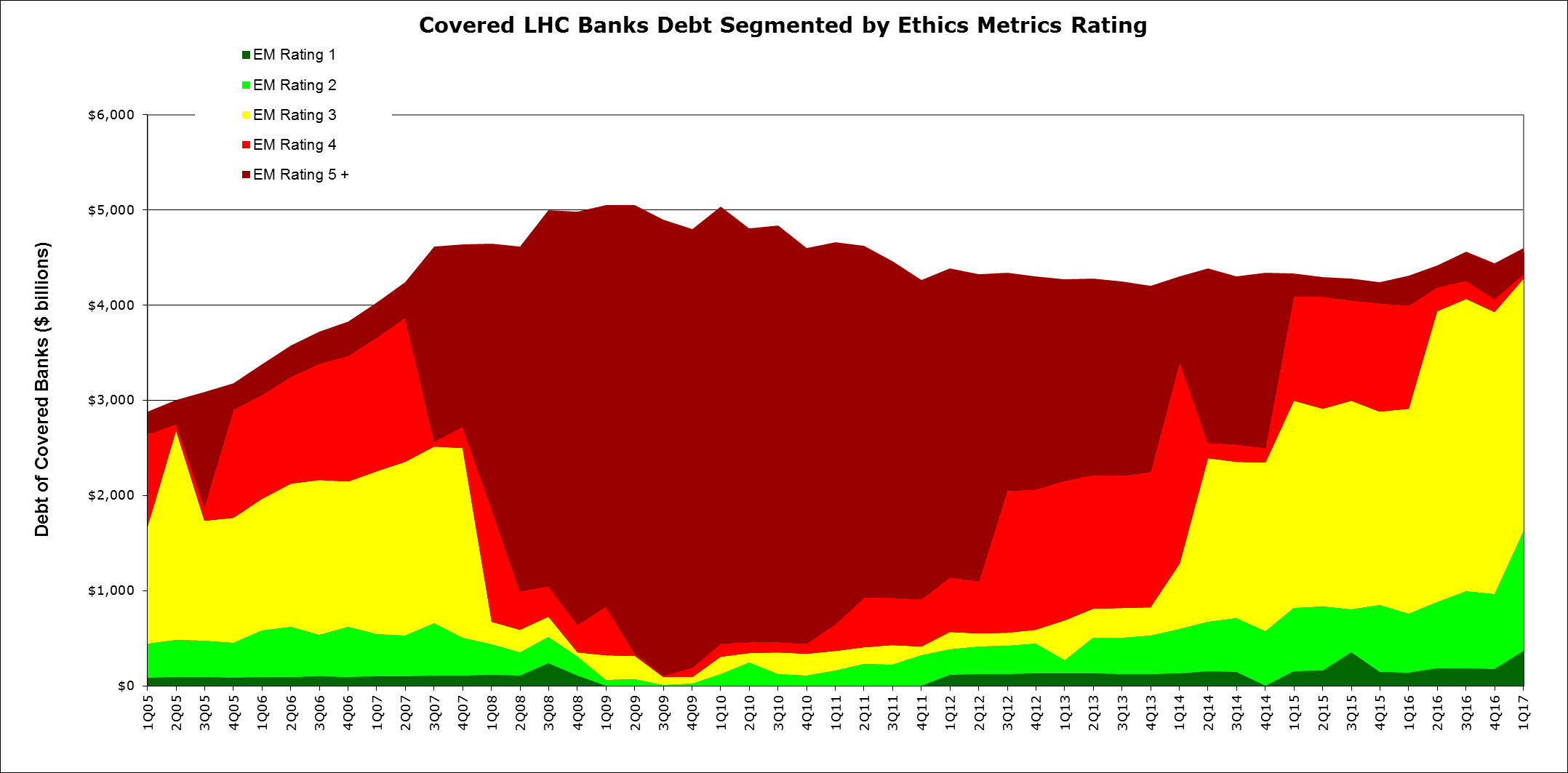

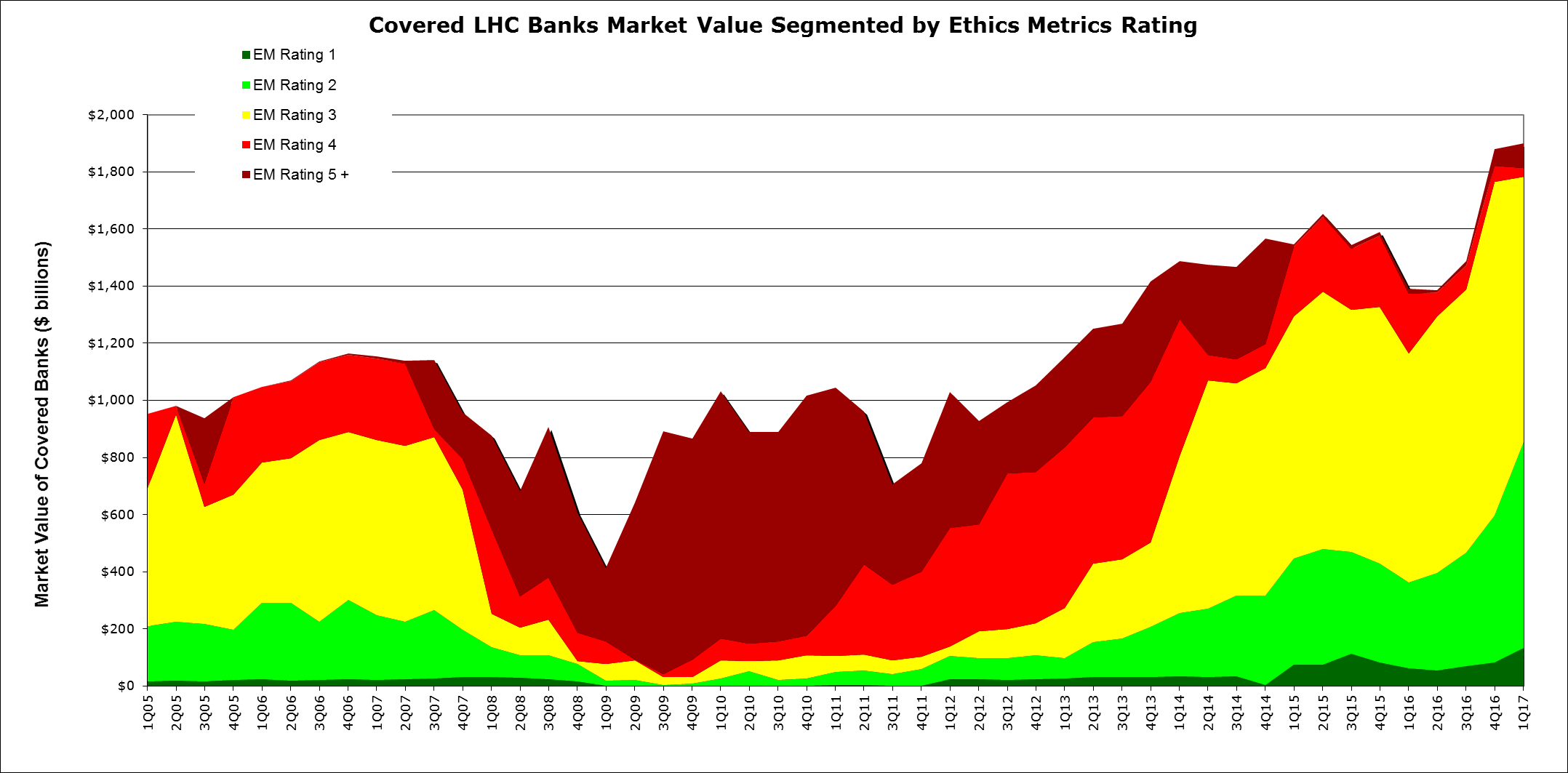

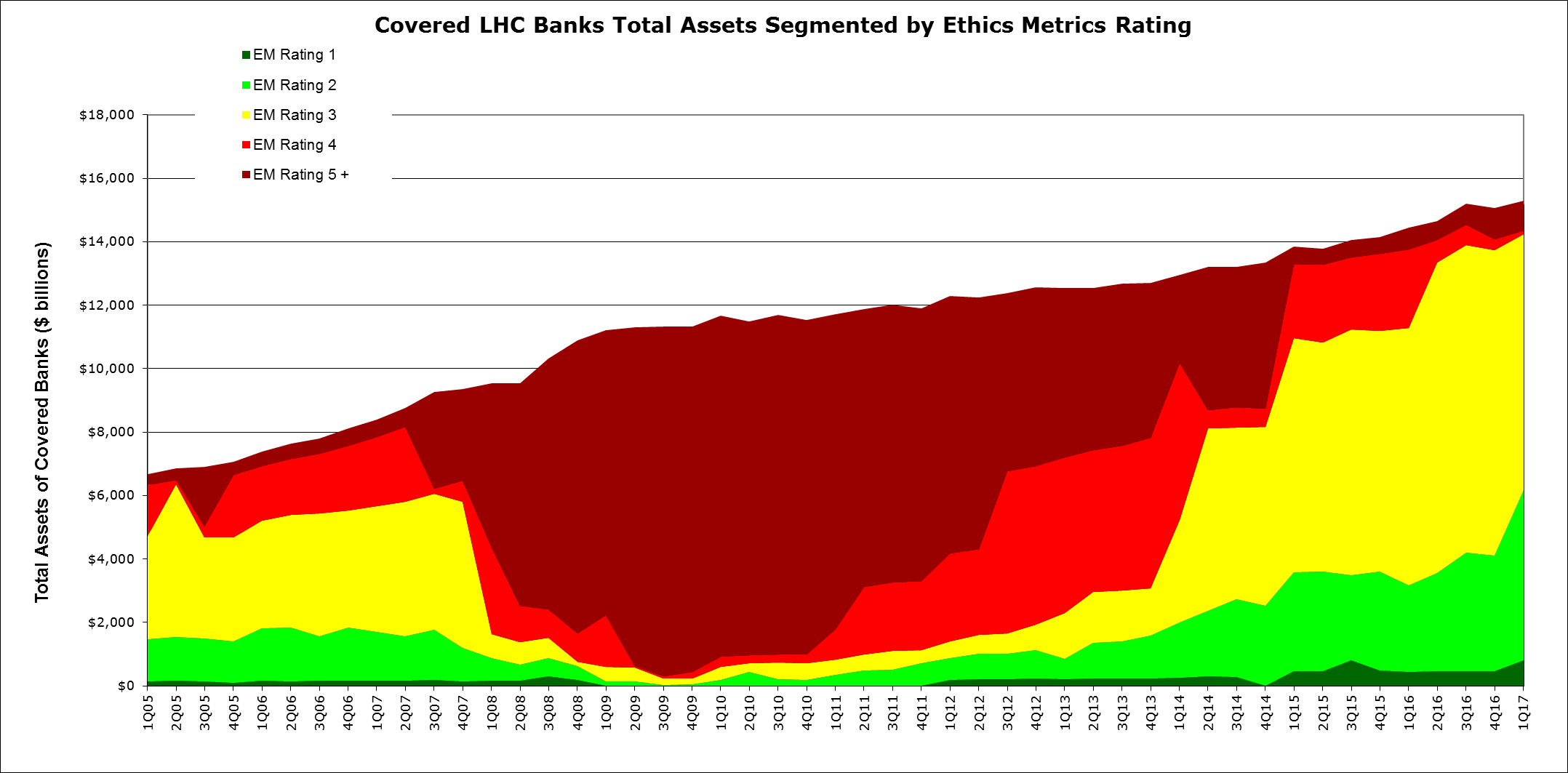

The quarterly Heat Map of Ethics Metrics Ratings for the 100 currently active, largest DIHCs provides insights on risk trends within the U.S. banking industry. However, such an overview indicates how many DIHCs are at risk and does not consider the relative dollar values at risk. To evaluate the aggregate levels of risk in the industry, the total dollars in Noncore Funding, Equity and Total Assets are each segmented within the Ethics Metrics Risk Rating.

The next set of Charts in the Addendum features the relative Values at Risk for Noncore Funding, Equity and Total Assets based on each of the corresponding quarterly DIHC Ratings for each of the 100 currently active, largest DIHCs from 1Q2005 to the present.

The 100 currently active, largest DIHCs have increased their market share of total IDI assets in the U.S. banking industry from 54% in 1Q2005 to almost 80% as of 1Q2017. Information asymmetries within this group now conceal fraud and systemic risks potentially affecting $13.3 trillion, or 78%, of the $16.9 trillion of total assets of the U.S. banking industry.

Conclusion

Greater transparency through advanced analysis of publicly available information and related subscriptions to independent DIHC Reports by Ethics Metrics combine to increase market discipline in a highly inefficient market, one currently distorted by information asymmetries, permitted by federal bank regulators, that favor large, active DIHCs that own 78% of the total assets of the U.S. banking industry.

Addendum—Systemic Risk Dashboard for 100 Currently Active, Large DIHCs: 1Q2005 to present

Chart #1: FSOC’s Quarterly Bank Health Index, 1Q2005 to 2Q2017

https://www.financialresearch.gov/financial-stability-monitor/

Chart #2: Quarterly Heat Map of DIHC Ratings for each of the 100 Currently Active, Largest DIHCs: 1Q2005 to Present

Chart #3: Noncore Funding Values at Risk for the 100 Currently Active, Largest DHICs: 1Q2005 to Present

Chart #4: Equity Values at Risk for the 100 Currently Active, Largest DHICs: 1Q2005 to Present

Chart #5: Total Asset Values at Risk for the 100 Currently Active, Largest DHICs: 1Q2005 to Present

Table #1: Summary of Total Values for the 100 Currently Active, Largest DIHCs, March 31, 2017

| Equity Market Value of Publicly Traded DIHCs | $1,900,351,854,000 |

|---|---|

| Noncore funding (from BHCPR) | $4,750,000,000,000 |

| Total Assets of Insured Depository institutions (IDIs) | $13,289,148,712,000 |

| Total Assets (From FR Y-9C) | $15,299,239,997,000 |

| Total IDI Assets in U.S. Banking Industry | $16,965,782,000,000 |

| OTC derivatives cleared through a central counterparty | $75,356,834,113,000 |

| OTC derivatives settled bilaterally | $72,843,553,100,000 |

| Total notional amount of OTC derivatives | $148,200,387,213,000 |

| Total IDI assets of 100 DIHCs as % of Industry’s Total IDI Assets | 78% |

Endnotes:

1Presidential Executive Order on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System, February 3, 2017.

www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/02/03/presidential-executive-order-core-principles-regulating-united-states

(go back)

2Ethics Metrics, Analysis of Bank Holding Company Disclosures, comments submitted May 8, 2017 to the SEC on its Industry Guide 3, Statistical Disclosure by Bank Holding Companies as well as in the Financial Stability Board’s Thematic Review of Corporate Governance, dated April 28, 2017. See paragraph 2.2.2.(go back)

3A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities, Banks and Credit Unions, by the U.S. Treasury. June 12, 2017. www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/A%20Financial%20System.pdf

(go back)

4Dodd Frank Stress Test Results for 2017, June 22, 2017. www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/dfa-stress-tests.htm

(go back)

5Section 2128.05, Securitization Covenants Linked to Supervisory Actions or Thresholds (Risk Management and Internal Controls), Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual, July 2005. www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/bhc.pdf

(go back)

6Section 4070.5, Nondisclosure of Supervisory Ratings, Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual, July 2008. www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/bhc.pdf(go back)

7Instructions for the Capital Assessments and Stress Testing, Information Collection (Reporting Form FR Y-14A), Modified May 23, 2017 www.federalreserve.gov/reportforms/forms/FR_Y-14A20161231_i.pdf www.federalreserve.gov/apps/reportforms/reportdetail.aspx?sOoYJ+5BzDa2AwLR/gLe5DPhQFttuq/4(go back)

8Federal Reserve’s BHCPR, Noncore funding, A User’s Guide for the Bank Holding Company Performance Report (BHCPR).

www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/BHCPR_Publication_2017_03_FINAL.pdf(go back)

9Federal Reserve’s BHCSM, Volatile source of funds, Section 2080.05.1, Funding and Liquidity, Federal Reserve’s Bank Holding Company Supervision Manual (BHCSM).

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/bhc.pdf

(go back)

10Federal Reserve’s BHCPR, op.cit.(go back)

11Federal Reserve’s BHCSM, op. cit.(go back)

12IBID.(go back)

13Ethics Metrics, op. cit. Page 1.(go back)

14Ethics Metrics’ posting, Déjà Vu: Model Risks in the Financial Choice Act, June 25, 2017, on this Forum.(go back)

15FR Y-15 Reports by DIHCs with assets above $50 billion are filed with the Federal Reserve and reported through the FFIEC’s National Information Center. https://www.ffiec.gov/nicpubweb/nicweb/HCSGreaterThan10B.aspx(go back)

16Financial Stability Monitor, Office of Financial Research, Financial Stability Oversight Council. www.financialresearch.gov/financial-stability-monitor/(go back)

17Ethics Metrics, op. cit. Paragraph 2.2.2.(go back)

Print

Print