Ryan Krause is Associate Professor of Strategy in the Neeley School of Business at Texas Christian University; Mike Withers is Assistant Professor of Management in the Mays Business School at Texas A&M University; and Matthew Semadeni is Professor of Strategy at Arizona State University W.P. Carey School of Business. This post is based on a recent article, forthcoming in the Academy of Management Journal, and originally published in The Conference Board’s Director Notes series.

Many companies now use lead independent directors, yet little is known about when they are elected, who is selected, what impact their selection has on performance and if their selection prevents the future separation of the CEO and chair positions. We explore these four questions using a power perspective and largely find lead independent directors represent a power-sharing compromise between the CEO/chair and the board.

* * *

A critical issue of board governance is the tradeoff of joining or separating the CEO and board chair roles. Joining the roles provides the organization the unity of command, with a single individual leading the firm. This is very important in dynamic environments where strong leadership is required and the CEO/chair must communicate clearly to multiple audiences. Also, it can provide the board greater insight into the day-to-day operations of the firm since the leader of the board is also managing the firm. But joining the roles puts at risk the oversight role of the board since its leader is one of those it is evaluating. This has been colloquially referred to as “CEOs grading [their] own homework”. [1] To prevent this, many have argued that the CEO and chair positions must be separated to prevent the conflict of interest inherent to the CEO leading the board.

Highlights

- Power balance between the CEO and the board is a key determinant to lead independent director appointment and to who is selected.

- Lead independent director (LID) selection can affect firm performance and the likelihood of CEO/chair separation

- The managerial implication is that power-sharing can allow the CEO to remain board chair while preserving effective corporate governance

- An important open issue is the duties of the lead independent director remain vague and idiosyncratic to the individual and firm

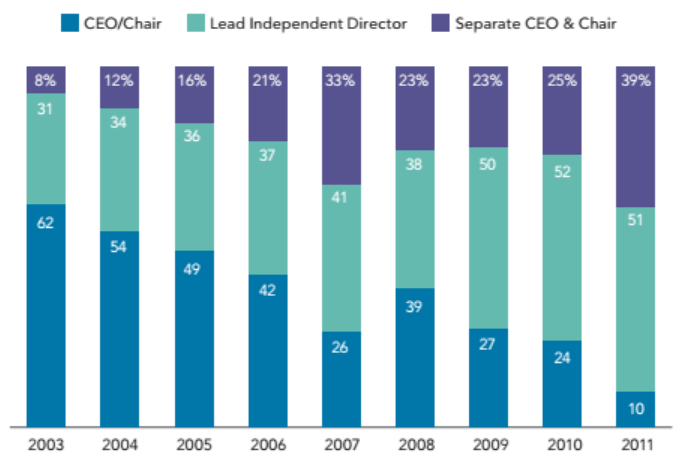

For many years these mutually exclusive options were the only ones available, requiring boards to accept the tradeoffs inherent to each option. In 1992, Lipton and Lorsch [2] proposed a third option: retaining the CEO as board chair and the appointment of a lead independent director. This compromise solution joined together the advantages of having a single leader with the advantages of having more independent board leadership. In the early 1990s, nearly 80 percent of large, U.S.-based firms had board chairs who were also the firm’s CEO, but the scandals of the early 2000s led to greater scrutiny of joining the CEO and board chair positions, leading many firms to consider appointing a lead independent director. This was furthered by a 2008 New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) policy change requiring that listed firms with CEO/chairs appoint a presiding director to lead executive sessions. [3]

The belief that a lead independent director appointment presents a compromise solution is supported by the 2013 Director Compensation and Board Practices report from The Conference Board in collaboration with Nasdaq OMX and NYSE Euronext. For companies selecting the lead independent director structure, almost 70 percent felt that board independence is achieved through a lead independent director, with financial services firms reaching almost 80 percent. In fact, this rationale was the most highly cited reason for having a lead independent director. The study also found that as the size of the firm increases (as measured in annual revenue), the belief that lead independent director appointment provides the necessary level of independence also increases.

But what is the role of the lead independent director? In 2012, Wall Street Journal reporter Joann Lublin wrote,

“Lead directors could be defined by what they aren’t—independent board chairmen who share the helm with powerful CEOs. Increasingly, however, the corporate governance community is seeing them as an effective counterweight anyway. The role is a compromise that developed in the wake of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Lawmakers…didn’t want to force companies to split the chairman and CEO jobs. What evolved was the appointment of a director to represent fellow board members, someone who didn’t have ties to the company.“ [4]

This perspective was echoed by a member of the Lead Director Network (LDN),

“Once you’re in the role, the conditions may change and therefore the definition of your job may change. The role will have to change on a dime if the conditions change, so we shouldn’t define the role too narrowly. The definition must be fluid enough to adapt to the situation.“ [5]

The LDN [6] identified three major ways in which lead independent directors add value to board operations:

- They can help develop a high-performing board by keeping it focused, coordinating across committees, and ensuring board members have the information they need.

- They can build a productive relationship between the board and the CEO/chair by ensuring effective communication and providing feedback to the CEO/chair from the board.

- They can support effective shareholder communication by being the contact person for shareholders.

While many anecdotal insights into the use and responsibilities of LID exist, there is almost no empirical investigation of them. To address this, we build on the notion that the appointment of a LID is a compromise between the two attractive, but mutually exclusive options of combining or separating the CEO and board chair roles. Since much of the concern around CEOs holding the chair role centers on the CEO’s power relative to the board, we adopt the perspective that the CEO’s power relative to the board will be a determining factor in the selection of board leadership. Using this perspective, our research sought to answer four questions:

- What leads to LID appointment?

- When a LID structure is selected, who is selected as LID?

- What effect on performance does appointing a LID have on various performance outcomes (specifically, holding period returns, ROI, and analyst recommendations)?

- What effect does LID appointment have on the likelihood of CEO/Chair separation?

When is a LID selected?

Our first question is under what power conditions is a LID selected. Power is generally conceptualized in relative rather than absolute terms. For example, a sports team may be the most powerful in its conference but when compared with all teams it is in the middle of the pack. Accordingly, power in corporate governance is most often conceptualized as the CEO’s power relative to the power of the board. To date most theory and research has focused on powerful CEOs or powerful boards (i.e., when one is able to control the other). This research has suggested that when the CEO is powerful relative to the board, he or she will retain the chair role. Conversely, when the board is powerful relative to the CEO the positions are most often separated. But what happens when the power is balanced? To answer this, we used a composite measure of CEO power relative to the board power. Confirming prior studies, we found that when CEO power relative to board power was high that the CEO retained the board chair role, and that when the board’s power was high relative to the CEO that the positions were separated. But consistent with the notion that LID appointment is a compromise, we found that a LID was most likely to be appointed when CEO power relative to the board was balanced. In other words, when neither the CEO nor the board was powerful relative to the other, a LID was appointed to reflect this sharing of power.

This finding presents strong evidence that as CEOs or boards move away from dominance and towards more balanced power, they will gravitate toward compromise solutions such as the lead independent director. In addition, the results revealed that while lead independent director appointment is most likely to occur when CEO power is moderate, the drop-off in CEO power between lead independent director appointment and CEO-board chair separation is larger than the drop-off between no change and lead independent director appointment. This suggests that CEOs who see their power as somewhat tenuous may opt for the compromise solution as a way to placate advocates of more structural change and stave off any further reduction in power.

Our Methodologya

To analyze LID appointment, we used a sample of S&P 1500 firms from 2002 to 2012 who had a combined CEO/Chair structure, resulting in 966 firms. We collected board and director level data from BoardEx database, from the Institutional Shareholder Services (formerly RiskMetrics) database, and from company proxy statements. Firm-level financial and market data were collected from Compustat and from CRSP. Analyst recommendations were collected from the Institutional Brokers Estimates System (IBES). Finally, ownership data were collected from the Thomson Reuters Institutional Holdings database. Due to missing data, our final sample was 522 firms.

We used several dependent variables in our analysis. Our first dependent variable assessed if the firm appointed a LID, separated the CEO and chair positions, or made no change (i.e., retained the CEO/chair structure). Our second dependent variable is binary set to 1 if a LID appointment occurs and 0 otherwise. Our next set of dependent variables centered on performance. First, to measure market performance we selected stock returns to buying and holding the stock for a calendar year. Second, to measure accounting performance, we selected return on investment (ROI), which is net income divided by total invested capital. Finally, for a stakeholder performance we measured median analyst rating, which can take on five ordinal values, from 1 (strong buy) to 5 (strong sell).b Our final dependent variable is binary, set to 1 if the firm separates the CEO/chair positions after appointing a LID and 0 if they do not.

Our analysis used several independent variables as well. First, we used a composite measure for CEO power that consists of CEO tenure relative to average board tenure, the number of outside boards on which the CEO serves relative to the average number of outside boards on which each director serves, the number of outside directors who are also current CEOs, board independence, and firm performance. We standardized each of these measures and summed them to produce a standardized index of CEO power. Second, to measure individual director power we use five indicators: director tenure, number of current board seats, whether the director is a business expert, elite educational background, and financial expertise. Similar to our measure of CEO power, each of these individual variables was standardized and summed for each director-year observation to produce an index of director power. Finally, we use LID appointment as a binary variable measured as 1 if the CEO and board chair positions remained combined but an independent board member was appointed to the lead director position in a given year, and 0 otherwise.

Our analysis also contained numerous control variables such as firm size, CEO turnover, firm ownership, litigation, board interlocks, CEO equity pay, and environmental dynamism, complexity and munificence.

To analyze the data we used several forms of multiple variable regression (generalized linear latent and mixed models, fixed-effects logit, fixed-effects regression, and Cox proportional hazard) depending on the analysis being conducted.

- Please see the article in Academy of Management Journal for a comprehensive explanation of data, measures, and empirical analyses.

- We reverse coded this variable to aid in interpretation.

Who is selected as LID?

Intrigued by this finding, we examined who is selected as the LID when the firm chooses to appoint one. If power is indeed being shared between the CEO and the board, then the individual selected should embody this power-sharing. This implies that the person selected as the LID will be neither the most powerful independent board member nor the weakest. This is because if the most powerful independent director were selected, the individual might be seen as a challenger to the CEO, but if the weakest independent director were selected, he or she may be perceived as a leader in name only with no real power to control or influence the CEO/chair. To measure this, we examined the power levels of each of the independent board members relative to the other independent board members. We found that the most likely independent director selected is one with a moderate level of power. This supports the notion that the person selected as LID is as important as the decision to appoint a LID.

Taken together, these findings provide compelling evidence that CEOs and boards are compromising in both the decision to appoint a lead independent director and in who is designated as the lead independent director. This is significant as it demonstrates that the designation of a lead independent director is more than a symbolic gesture to appease the arbiters of good corporate governance; rather it indicates that the board is conscientious about who it selects for the role.

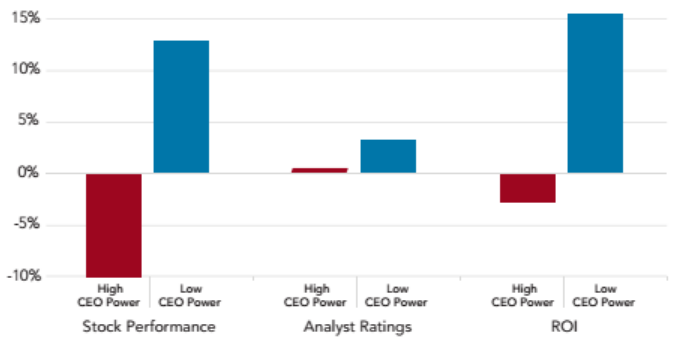

What effect does LID appointment have on performance?

Appointment of a LID impacts corporate governance outcomes, but we wanted to know if it influenced performance. In other words, if the firm has adopted a power-sharing arrangement between the CEO/chair and the board, does that affect firm outcomes? Because firm performance can be measured in many different ways, we selected market, accounting, and stakeholder performance measures, specifically:

- Annual stock returns

- Return on Investment (ROI)

- Median analyst recommendation

Our results further support the importance of the power perspective to LID appointment. For the market and accounting measures we found no main effect of LID appointment on performance. [7] In other words, simply appointing a LID director does not affect either market or accounting performance. To explore the influence of power on this, we then examined the effect of LID appointment when the CEO/chair holds a moderate to low level of power. We reasoned that, in keeping with the power-sharing inherent to LID appointment, having a strong CEO/chair would limit the impact of the LID appointment. We found that when a LID is appointed and the CEO has a low to moderate level of power, there is a positive effect on market and accounting performance, underscoring the importance of relative power to the usefulness of having a LID. Turning to our stake-holder performance measure, we found a positive main effect of LID appointment on median analyst recommendation, and this performance effect is stronger when the CEO holds a moderate to low level of power. This suggests that analysts view LID appointment favorably and that this favorable view is stronger when the power is balanced between the board and the CEO/chair.

Chart 1: Performance Effect Difference between No LID & LID

Source: “Compromise on the Board: Investigating the Antecedents and Consequences of Lead Independent Director,” the Academy of Management Journal (forthcoming)

In addition, the positive main effect for analyst ratings but not for the other performance measures suggests that analysts respond to the symbolism of the appointment in a manner that objective metrics such as stock and accounting performance do not.

Given its outward appearance of conformity to firm oversight, it is not surprising that lead independent director appointment garners a positive overall reaction from analysts. Prior research has shown that analysts’ view increases in a board’s structural independence as positive, even when such structural changes do not produce meaningful improvements in firm governance. [8]

In contrast to the main effect, which only manifested for analyst ratings, the interaction of CEO power and lead independent director appointment was significant across all three performance measures. This suggests that appointing a lead independent director amounts to little more than window dressing when CEO power is high, but can have positive performance effects when CEO power is low. (We look at the relationship one standard deviation below and above the mean CEO power level using the CEO power measure described earlier.) Together, these results provide evidence that when the CEO is not totally dominant, the lead independent director can strike a balance between having a single leader and having proper oversight. In addition, when the CEO is dominant, the lead independent director still serves a symbolic role in placating external observers like securities analysts.

What effect does LID appointment have on separation?

Finally, we were curious about how the appointment of a LID affected the likelihood that the firm would decide to separate the CEO and chair roles in the future. If the power-sharing compromise is functioning well, then the firm may feel that separation is not necessary and the likelihood of separation will fall. To measure this we examined the likelihood of separation after the appointment of a LID and found that it decreases the likelihood of separation by almost 60 percent. Importantly, we controlled for the effect of CEO power on the likelihood of separation, given that past research has shown that CEO power by itself decreases the likelihood of separation. The effect of CEO power on separation was found to be around 33 percent. [9] We then statistically compared these two effects and found that LID appointment had a statistically higher negative effect on the likelihood of separation than CEO power. Finally, we felt that perhaps the lowest likelihood of separation would occur when a LID is appointed and the CEO has high power, but testing this we found that there was no interactive effect. This means that increasing CEO power does nothing to decrease the likelihood of separation beyond the decreased likelihood from LID appointment. In other words, appointing a LID has a stronger negative effect on separating the CEO and chair positions than CEO power, and increasing CEO power doesn’t further enhance that negative effect. The implication is that lead independent director appointment provides significant protection to the CEO/chair, independent of the CEO’s power.

Chart 2: Sample Governance Structure (by year)

Source: “Compromise on the Board: Investigating the Antecedents and Consequences of Lead Independent Director,” the Academy of Management Journal (forthcoming)

Managerial Implications

The findings of our research have several implications for corporate governance practitioners. First, balancing power between the board and the CEO does not necessarily lead to a governance impasse. We find that at parity, both the board and the CEO are willing to make important concessions to the other to fashion a functioning governance arrangement for the firm. This leads to a second implication, which is that the sharing of governance between the board and CEO is legitimate in nature. In other words, the agreement of the CEO to permit the appointment of a lead independent director of moderate power coupled with the willingness of the board to accept a lead independent director rather than calling for the separation of the CEO and board chair positions suggests a meaningful compromise. If, for example, the CEO would only accept a lead independent director with weak power, or if the board required that the lead independent director be very powerful, governance would be much more problematic and the benefits of the lead independent director would be tenuous. We see this outcome emerge in our analyses of performance outcomes; lead independent director appointment can improve firm performance, but only if the CEO is not very powerful. Finally, despite the calls from corporate governance regulators and consultants for all CEOs to relinquish the chair role, [10] our research suggests that boards and CEOs can reach a compromise that preserves the unity of command provided by CEO duality while not sacrificing robust corporate governance, as evidenced by both the performance consequences and the staying power of the lead independent director position.

Open Questions

While we provide insight into the effect of power on LID appointment, several important open questions remain.

- First and foremost, while the position of LID has become more legitimate, the role the LID plays on the board remains very fluid with many unknowns. For example, it is clear that the LID is a conduit between the board and the CEO/ chair. Reflecting this, a LDN member stated, “It’s my job to make sure that every director’s perspective is aired and addressed during board meetings, especially if there are differences of opinion.” [11] But what is the LID’s role in setting corporate strategy, in risk management and in crisis management, such as when the firm’s management is under investigation?

- Second, how does either CEO/chair or LID succession change the corporate governance? If the LID appointment reflects a power sharing between the CEO/ chair and the board, changing either the CEO/chair or the LID could shift the balance of power and make the structure untenable.

- Finally, as LIDs are increasingly used by boards, will experience as a LID emerge as a characteristic that makes a director more attractive?

Until recently, corporate governance has conceptualized board leadership as a tradeoff between unity of command and independent monitoring. The lead independent director position directly challenges this conceptualization, however, as it constitutes a compromise between the competing theoretical prescriptions. In our research, we examined this compromise board leadership structure and explore its antecedents and consequences. We find that it reflects balanced power on the board, and that it can be beneficial when the circumstances are right. It is our hope that these insights will help to guide corporate governance, particularly in the area of board leadership.

* * *

The complete article is available for download here.

Endnotes:

1James A. Brickley, Jeffrey L. Coles, and Gregg A. Jarrell, “Leadership Structure: Separating the CEO and Chairman of the Board,” Journal of Corporate Finance, 1997 pp. 189-220.(go back)

2The NYSE requires that non-management directors meet at regularly scheduled executive sessions, that there are mechanisms for selecting a non-management director to preside at such sessions, and that companies provide a way to communicate with the presiding director (or the non-management directors as a group). See NYSE Euronext, Listed Company Manual, section 303A.03, “Executive Sessions”.(go back)

3Martin Lipton and Jay W. Lorsch, “A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance,” Business Lawyer, 1992 48 (1): 59-77.(go back)

4Joann S. Lublin, “Lead Directors Gain Clout as Counterweight to CEO,” Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2012.(go back)

5Lead Director Network ViewPoints, Tapestry Network, Issue 1, July 30, 2008, page 3.(go back)

6Ibid.(go back)

7By main effect, we mean the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.(go back)

8See Westphal, James D. & Graebner, Michelle E. 2010. “A matter of appearances: How corporate leaders manage the impressions of financial analysts about the conduct of their boards.” Academy of Management Journal, 53(1): 15-44.(go back)

9In other words, for every standard deviation increase in CEO power, the likelihood of separation decreased by around 33 percent.(go back)

10For examples of this, see MacAvoy, P. W. & Millstein, I. M. 2004. “The recurrent crisis in corporate governance,” Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Business Books. and Monks, R. A. G. & Minow, N. 2008. Corporate governance (4th ed.) Chichester, England ; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.(go back)

11Lead Director Network ViewPoints, Tapestry Network, Issue 10, March 24, 2011, page 6.(go back)

Print

Print