Markus Ibert is a PhD student at the Stockholm School of Economics; Ron Kaniel is the Jay S. and Jeanne P. Benet Professor of Finance at the University of Rochester Simon Business School; Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh is David S. Loeb Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business; and Roine Vestman is Assistant Professor at Stockholm University Department of Economics. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Ibert, Professor Kaniel, Professor Van Nieuwerburgh, and Professor Vestman. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Regulating Bankers’ Pay by Lucian Bebchuk and Holger Spamann; The Wages of Failure: Executive Compensation at Bear Stearns and Lehman 2000-2008 by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Holger Spamann; and How to Fix Bankers’ Pay by Lucian Bebchuk by Lucian Bebchuk (discussed on the Forum here).

A substantial part of investment management is delegated to institutions such as mutual funds, pension funds, university endowments, and hedge funds. Mutual funds account for a significant part of this market. Prior research has mostly been silent on the important distinction between the fund family and the managers it employs to manage its different funds.

Understanding compensation of fund managers is paramount to understanding agency frictions in asset delegation, yet little is known about the nature of these compensation contracts, and even less about actual compensation managers earn.

In Are Mutual Fund Managers Paid for Investment Skill?, we construct a unique data set containing information on the income of Swedish fund managers over the period January 1994 to December 2015. The data enable a first-time peek into the fund family “black box” to start discerning the role of managers within the fund families they work for. We find intriguing results that challenge common perceptions.

As we elaborate in the paper, Sweden is a good laboratory to investigate the mutual fund industry. It has one of the deepest and most competitive fund sectors. It is representative in terms of fund return performances and fees charged, in developed countries. Furthermore, pay culture for skilled labor may not be that different from that in the U.S.: recent evidence on the elasticity of CEO pay to firm assets shows it is similar in the two countries.

Managers’ Cut

In the mutual fund industry, the predominant contract between investors and funds is one where fees are proportional to asset under management. A key question is what the managers’ cut is and how it varies as revenues vary. Our data allows us a unique vantage point in helping to answer this question.

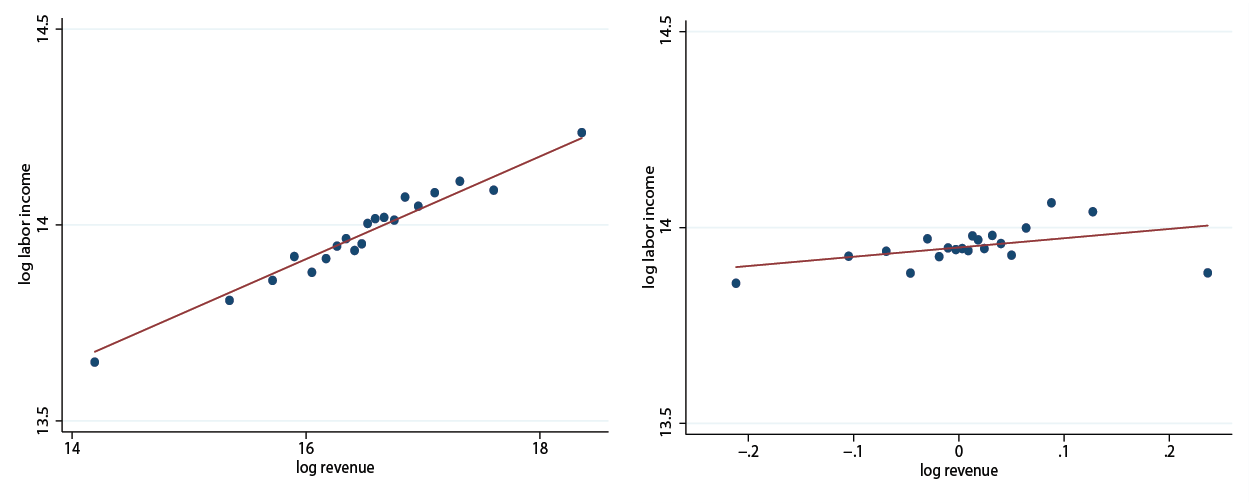

The left panel of Figure 1 plots log manager pay as a function of log manager revenue, a natural measure of size. [1] It shows a strong linear relationship between the two.

Figure 1. Elasticity of Pay to Revenue and Performance.

However, closer inspection reveals the slope is considerable lower than one, implying a concave relationship in levels. Using a regression analysis, we find an elasticity of compensation to revenues of 0.15. A one percent increase in revenues generated by this manager increases her compensation by 0.15%, lowering her share of revenue by 85%. A one-standard-deviation increase in revenues increases pay by 0.4 standard deviations, implying far from a complete pass-through of fund revenues to managerial compensation. Doubling of revenue from $6.2mi (avg.) to $12.4mi (AUM from $450 to $900mi) increases pay from $210,000 to $241,200, leading to a drop in the share of revenue going to managers’ pay from 3.3% to 1.9%. Owners, on the other hand, capture the bulk of revenue increases (99.5% in this example).

Theory suggests that a component of fund managers’ pay should be directly tied to return performance, especially when there is uncertainty regarding managers’ ability. We find a surprisingly weak sensitivity of pay to performance.

The right hand panel of Figure 1 shows the relationship between log labor income and log abnormal returns, where abnormal returns are defined as the gross (before fees) return in excess of the benchmark as stated in the fund’s prospectus. As apparent from the figure, the relationship is much weaker than the one between income and revenues.

A regression analysis shows that a one percentage point increase in abnormal return, not an inconsequential increase, raises pay by only 0.39%. A one standard deviation increase in abnormal return performance increases compensation by 0.04 standard-deviations; ten times less than a standard-deviation increase in revenue! The weak relationship persists even after accounting for potential non-linearity in pay to performance sensitivity and longer performance histories. It is mostly driven by talented managers generating higher returns, and earning higher income, rather than time series variations for a given manager.

Pay-performance sensitivity increases once components of revenue that are correlated with current and past abnormal returns, such as fund flows, are accounted for. However, even then, it remains economically small, and the component of revenue that is unrelated to past performance remains the dominant driver of pay. This suggests that an important component of mangers compensation may be for non-performance-related revenue-generating skills, such as asset gathering, sales & marketing, people management, etc.

The Role of the Fund Family

In the analysis discussed above, we found an economically modest effect of manager-level revenue on pay, and very low sensitivity of pay to manager-level performance. This leaves ample room for other determinants of pay. Mutual fund companies manage multiple funds, raising the possibility that manager pay depends not only on revenue and performance of funds she is responsible for, but also on revenue and performance generated by other funds in the same fund family.

We show that firm-level characteristics, typically ignored in the literature, add substantial explanatory power for manager compensation. The explanatory power of the regression (i.e., the R-squared) increases from 23% to more than 50% once we account for the common component of pay to managers within the same fund family in a given year. Furthermore, the elasticity of pay to firm revenue, excluding revenue managed by the given manager, is comparable to that of manager revenue. The elasticity is about half as large as that to manager revenue, but a one standard-deviation in log firm-level revenue is 50% larger than a one standard-deviation in log manager revenue.

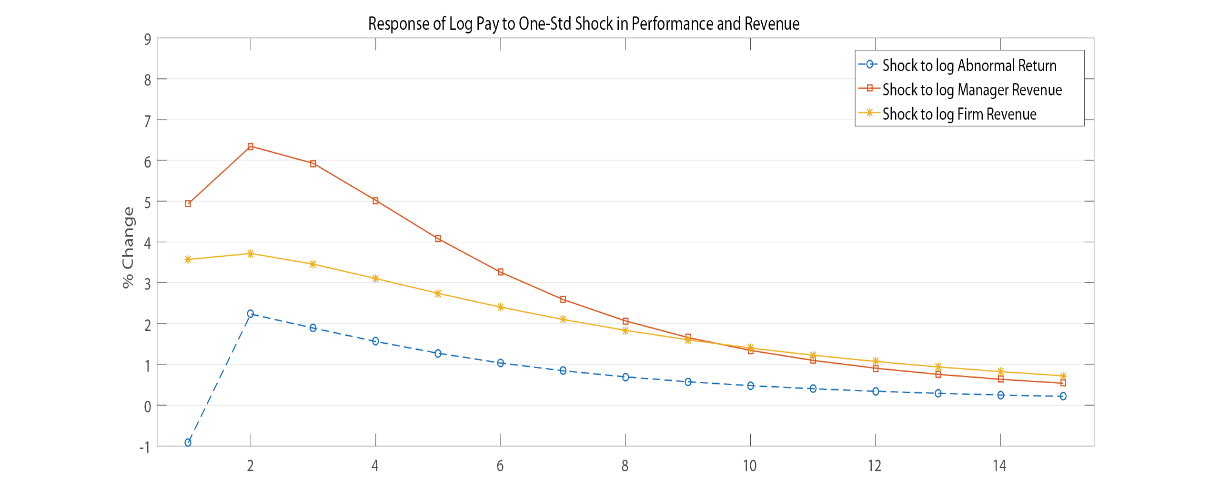

To further investigate the role of the three components (manager revenue, performance, and firm revenue), we conduct a joint Vector Auto Regression analysis and analyze the dynamic response of manager pay to shocks in each. Figure 2 plots the response, over time, of log pay to orthogonal one-standard-deviation shocks. The impact of firm-level revenue is 2/3 that of manager-level revenue, and at least as persistent. The impact of performance is the smallest and the least persistent.

Figure 2. Dynamic Response of Managerial Pay to Performance, Manager Revenue, and Firm Revenue Shocks

In further analysis, we show that firm profit also matters considerably. Firms with higher profits pay significantly more. At the same time, profitability lowers the sensitivity of compensation to manager revenues and increases that to performance.

The evidence we uncovered is consistent with a compensation package that contains one component that depends on manager-level revenues and another component that comes out of a firm-wide bonus pool. This bonus pool only exists when the firm makes a profit. Pay-for-performance is only present in profitable firms, but even there plays a small role in determining compensation.

Going Forward

Our analysis uncovers three novel facts that are instructive for research and practice on portfolio delegation going forward. Each of the following three findings is interesting in its own right and challenges common perceptions:

- a considerably lower sensitivity of pay to manager-level assets under management, compared to the fixed fraction of AUM typically charged by funds.

- a surprisingly weak sensitivity of pay to performance, even after accounting for potential non-linearity in pay to performance sensitivity and longer histories of performance.

- firm-level characteristics, typically ignored in the literature, add substantial explanatory power for manager compensation.

Our evidence highlights limitations of considering managers in isolation from fund families they work for. Managers are an integral part of a family and their incentives are shaped not only by how well they manage their own fund, but also by how they integrate within the rest of the family, their relative bargaining power, which depends on their added value, and the corporate culture. Consequently, intra-fund family incentive frictions will impact managers’ portfolio allocation decisions.

The full paper is available for download here.

Endnotes

1Results are similar if instead of revenues we use AUM.(go back)

Print

Print