David F. Larcker is James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting, Peter C. Reiss is MBA Class of 1963 Professor of Economics, and Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper.

We recently published a paper on SSRN, Critical Update Needed: Cybersecurity Expertise in the Boardroom, that evaluates the quality of information presented by management to directors in advance of board meetings. Below is a reproduction of the text.

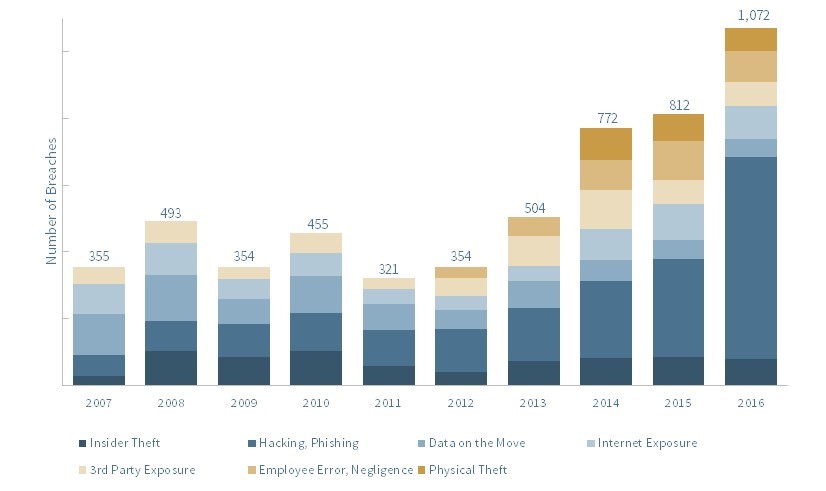

As part of its oversight responsibilities, the board of directors is expected to ensure that management has identified and developed processes to mitigate risks facing the organization, including risks arising from data theft and the loss of proprietary or customer information. Unfortunately, general observation suggests that companies are not doing a sufficient job of securing this data. Data theft has grown considerably over the last decade. According to the Identity Theft Resource Center, the number of data breaches tripled from 2007 to 2016. The main contributor to this increase was theft by third-party hacking, skimming, and phishing schemes (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Data Breaches by Category

Data breach is defined as an incident in which an individual name plus Social security number, driver’s license number, medical record, or financial record (including credit or debit card numbers) is potentially at risk because of exposure.

Source: Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC).

The cost of data theft is significant. According to the Ponemon Institute, the average direct organizational cost of a data breach in the United States is $7 million. This includes the cost to identify and contain the breach, notify customers, and loss of business. Class-action lawsuits add to this figure, with settlements ranging from approximately $1 million for moderate-scale data breaches to over $100 million for large-scale breaches. One study finds that the average stock declines 5 percent following the disclosure of a breach and performs negatively over the subsequent 90-day period. Clearly, cybersecurity is an important risk facing companies and their shareholders.

Incidents of Data Theft

Given the cost and likelihood of a successful cyberattack, it is important to ask whether boards and management have sufficient understanding and are appropriately prepared to prevent, monitor, and mitigate digital data theft (see Exhibit 2 for survey data). To shed light on this question, we reviewed prominent incidents of data theft over the last five years to understand the types of cyberattacks that occur and how companies respond to them.

Exhibit 2: Survey Data: Board of Directors on Cybersecurity

“How confident are you that your companies are properly secured against cyberattacks?”

“How often are cybersecurity matters discussed during board meetings?”

Sample includes approximately 200 directors of public companies.

Source: Veracode and New York Stock Exchange, “A 2015 Survey: Cybersecurity in the Boardroom,” (2015)

Customer Data. Payment and accounting system breaches are an important source of cyber risk. One of the largest attacks on a payment network occurred at Target in December 2013 when over 40 million accounts were compromised in a system-wide breach over a three-week period during the holiday shopping season. This attack was followed by several high-profile payment-system breaches at the Home Depot, Michaels Stores, Neiman Marcus, Supervalu, and Staples, as well as franchised owners of UPS Stores, PF Chang’s, and Hard Rock Café. The frequency of credit card breaches has been significantly reduced through chip-card requirements introduced by the major payment networks in 2016; however, they remain an important point of vulnerability.

Another type of data theft involves penetrating corporate networks or employee devices that store the personal information of clients and employees. This information is then sold in anonymous “dark” markets on the web. Recent examples of personal data theft include Morgan Stanley, Scottrade, and Standard Charter, where hackers or internal employees download the personal information of wealth-management clients, including names, account numbers, and investments. Similarly, health insurance networks such as Anthem, Primera, and CareFirst BlueCross have been targeted by cybercriminals who steal the names, birthdays, addresses, social security numbers and health information of customers. One of the largest breaches of personal data occurred in September 2017 when the credit-reporting firm Equifax reported that personal information on 143 million customers was exposed.

A more unusual example of personal data theft occurred in September 2014 when hackers accessed the Apple iCloud data storage accounts of targeted celebrities, such as actresses Jennifer Lawrence and Kirsten Dunst and model Kate Upton, and stole their personal photos and videos, some of which were released publicly. The individual responsible for hacking these accounts was sentenced to 18 months in prison. To improve security, Apple introduced technology to provide automatic email notification when an iCloud account is accessed from a new device or browser.

Corporate Systems and Data. Customer data is not the sole target of cybercriminals. In 2014, the North Korean government attacked Sony Picture’s IT infrastructure in an attempt to intimidate the company into not releasing a comedy film titled The Interview, which featured a fictional plot to assassinate North Korea’s real leader. Hackers inserted a malware program, which wiped out half of the company’s computers and servers with a sophisticated algorithm that made data recovery nearly impossible. Sony withheld release of the movie from most theaters but later made it available on demand and in select locations. Similarly, in 2017, rumors circulated that hackers had infiltrated Disney Studios and stole a copy of a forthcoming sequel to the movie Pirates of the Caribbean. Reports alleged that the hackers demanded “an enormous amount of money” in Bitcoin in order not to release the firm. Disney, in cooperation with the FBI, eventually determined that the hack had not been successful.

Company products also are subject to cyber threats when hackers access and assume control over products. The variety of products vulnerable to such attacks is remarkably broad. For example, in 2015 Fiat Chrysler recalled 1.4 million Jeep vehicles after it was determined that a cybersecurity flaw allowed hackers to remotely assume control of the car through wireless communication systems. The company had been aware of the security flaw but issued the recall when it discovered that hackers could remotely control the car’s brakes, transmission, and other electronics. In 2016, a short-selling research firm released a report that cardiac implants produced by medical device company St. Jude Medical were vulnerable to cyberattack. A third party confirmed that in proprietary testing it was successful in gaining control over the company’s Merlin@home implantable cardiac devices that wirelessly monitor patient heartbeat and was able to remotely turned off the devices or, alternatively, deliver an extreme shock that would lead to cardiac arrest. The company subsequently updated product software to reduce the risk of remote access.

Companies are also vulnerable to the theft of proprietary technology or methods of production. In 2016, US Steel was attacked by hackers allegedly linked to the Chinese government who stole methods for producing lightweight steel. That same year, Monsanto discovered that an employee had been working with a foreign government to steal information on the company’s advanced seed technology. The employee loaded “highly sophisticated and unauthorized software” on his computer that allowed a foreign government to monitor his activity remotely and transmit proprietary data.

More mundane but potentially more lucrative cybercrimes involve the theft of corporate information shared between companies and their advisors. For example, in 2016, prominent law firms Cravath Swaine and Weil Gotshal were among a number of law firms hacked by cybercriminals who stole nonpublic information on corporate clients, which could potentially be used for insider trading. Similarly, the servers of accounting firm Deloitte were hacked and files for a small number of clients were accessed. In 2017, the Securities and Exchange Commission revealed that Edgar, the database that stores the corporate filings of all publicly traded companies listed in the U.S., had been accessed, although the agency did not detail what information was stolen.

Finally, companies and their supply chains have been compromised by ransomware attacks in which cybercriminals disrupt computing systems or demand payment under threat of disrupting systems. Two major attacks occurred in 2017. The first involved a ransomware program called WannaCry which infected computers running Microsoft Windows operating system. The program automatically encrypted computer data and demanded payment in Bitcoin for its release. Over 200,000 computers in 150 countries were affected. FedEx and Nissan reported being materially impacted. A second malware attack in July 2017 took down the computing systems of major multinational corporations—such as Merck, Mondelez, and Maersk—and disrupted business operations over multiple days. Maersk announced that widespread computer outages prevented the company’s shipping subsidiary from booking new shipments and providing quotes at selected terminals. Mondelez estimated that the attack reduced second-quarter revenue growth by 3 percentage points.

Corporate Response to Cyberattacks

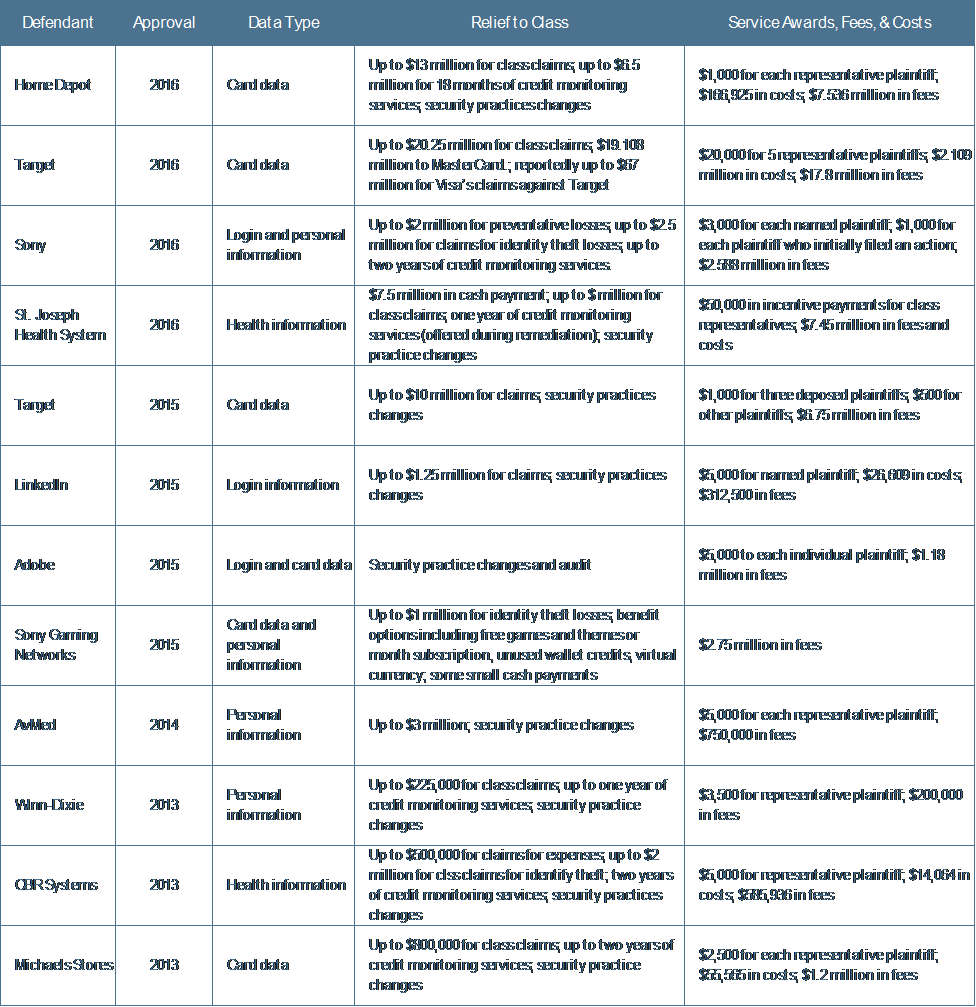

What actions do corporations take in response to cyberattacks such as these? Many announce steps to improve data security. When customers are affected, they make assurances about their commitment to data protection and offer free credit or identity-theft monitoring. Almost invariably, the company is sued and enters into a settlement (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Cost to Settle Class Action Lawsuits for Data Theft

Source: Alexander H. Southwell, Eric Vandevelde, Ryan Bergsieker, and Jeana Bisnar Maute, “Gibson Dunn Reviews U.S. Cybersecurity and Data Privacy,” The CLS Blue Sky Blog (Columbia Law School), (February 3, 2017). Selected data 2013 to 2016.

Beyond this, however, surprisingly little happens in terms of holding individuals accountable or structural changes that improve cybersecurity expertise at the senior-executive and board levels. For example, among a sample of approximately 50 cybersecurity breaches over the last five years, we find that the CEO is fired or steps down in only a handful of cases. Exceptions include massive data breaches such as those at Target, Equifax, and the website Ashley Madison, in which hackers stole and published the names of 32 million (potentially unfaithful) clients. Executive pay is almost never reduced. The CEO of Target received no bonus and forfeited $5 million in pension benefits after 40 million credit card accounts were stolen; however, the CEO of the Home Depot suffered no decrease in compensation after more than 50 million credit card accounts were stolen.

Furthermore, executives below the CEO are also rarely fired or penalized. The chief information officer (CIO) of Target was terminated along with that company’s CEO. The chief information security officer (CISO) of credit agency Experian was fired after information on 15 million customers was exposed. At Equifax, both the CIO and CISO were terminated along with the CEO. The head of Sony Pictures was fired after the North Korean hack of the company’s movie studio; however, Sony’s CISO kept his job. We see no evidence of executive terminations—CEO, CFO, CIO, CISO, or other C-suite level executive—following dozens of other high-profile cyberattacks.

Some companies hire forensics firms or cybersecurity experts in the aftermath of data breaches. Cybersecurity firms are brought in to assess how the breach happened and what assets were compromised. Cybersecurity experts are brought in to fill gaps in the firm’s internal ranks. For example, JPMorgan hired a former cybersecurity executive from Lockheed Martin a year after the bank discovered that hackers gained access to more than 90 bank servers after stealing the login credentials of a JPMorgan employee. The company also announced plans to increase its data security budget from $250 million to $500 million. Fiat Chrysler took additional steps. After it was discovered that cybercriminals could remotely gain control over its Jeeps, the company developed a program of hiring hackers to identify vulnerabilities in its products and offered to pay between $150 and $1500 for each legitimate security flaw identified.

Few companies add a cybersecurity expert to the board following data breaches. The Home Depot added an IT executive from Lockheed Martin. Neiman Marcus added the chief digital offer from Starbucks after Neiman’s payment systems were compromised. Uber recruited the former director of the U.S. Secret Service to serve on an advisory board—not the formal board of directors—a year after hackers stole personal information on 50,000 of its drivers. The hire, however, was part of a broader effort to reduce risk and increase safety for riders, drivers, and the public and not specifically heralded as an increase in security of the company’s systems.

We find little less evidence of formal governance changes following cyberattacks. The most commonly observed change is increased disclosure in the proxy. Following hacks, the boards of Coca-Cola, Monsanto, Home Depot, and Staples added specific mention of cybersecurity as a responsibility of the audit committee. Morgan Stanley added language that cybersecurity is a responsibility of its operations and technology committee. Standard Charter added it to its “risk review.” Target added data security as a “collective experience” of the board.

We found only one instance of a company making changes to an executive compensation plan to incorporate cybersecurity risk. JPMorgan added cybersecurity as part of the annual performance plans of both its CEO and COO.

Whether governance changes such as these are sufficient to compensate shareholders for the costs incurred in a cyberattack is unclear. Verizon Communications reduced the amount that it offered to pay for Yahoo!’s internet properties by $350 million after Yahoo! disclosed that hackers had stolen the birthdays, email addresses, and passwords of over 1 billion users (later increased to 3 billion users). A spokesperson for Yahoo! described the reduced purchase price as “a fair and favorable outcome.”

To decrease the risk of a cyber threat, some experts recommend the following:

- Elevate cybersecurity within the company’s risk framework. The board should ensure that management and employees take cybersecurity seriously. They should periodically review the company’s potential exposure and cybersecurity policies.

- Develop an action plan to respond to a breach in customer data. The plan should outline employee and board responsibilities, who should be contacted and when, how the company will communicate to the public, and how the breach will be assessed.

- Implement additional safeguards to protect corporate data. Management and the board should review who has access to critical corporate data and trade secrets, and develop policies around how this information is documented, stored, accessed and shared within the company. The board should have its own cybersecurity policies to protect director communications, documents, and conversations.

The complete paper, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print