Gail Weinstein is senior counsel, and Philip Richter and Steven Epstein are partners at Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP. This post is based on a Fried Frank publication by Ms. Weinstein, Mr. Richter, Mr. Epstein, Scott B. Luftglass, Warren S. de Wied, and Matthew V. Soran, and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

Appraisal, Corwin, Controllers, Director Self-Interest, Disclosure, M&A Agreements, MLPs, Financial Advisors

Below, we (i) outline the key developments in M&A law in 2017; (ii) review the transformation that has occurred since 2014; and (iii) summarize the Delaware courts’ major 2017 decisions.

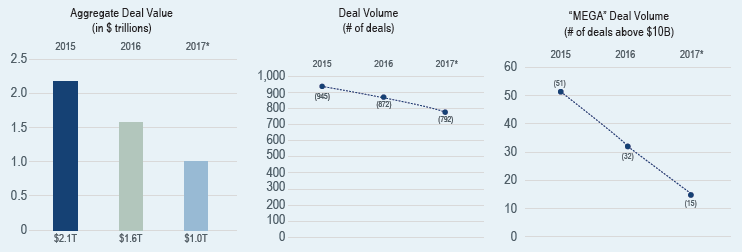

Decline in U.S. M&A Activity from Record Highs in 2015

Data derived from FactSet database for transactions over $100M where one of the parties (or its parent) was a U.S. public company.

*Annualized as of 11/1/17.

U.S. public company M&A activity was up 114% in 2014 from 2013, and increased to record levels in 2015. The trend of strong activity continued through the first half of 2016, followed by a significant drop-off in activity in the second half of 2016, which intensified through 2017. The drop-off can be attributed to the political uncertainty evident nationally and globally; uncertainty as to the direction of the economy; the higher equity valuations of companies as well as higher premiums being paid; the decline in “tax inversion” transactions following regulatory changes designed to curb them; a trend toward a focus on core businesses and utilizing M&A for more specialized, targeted growth rather than general expansion; and the frequent occurrence of “broken deals” (often due to antitrust or regulatory scrutiny).

Key Developments in 2017

Litigation. There has been a significant shift by plaintiffs away from bringing fiduciary duty actions in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Instead, M&A transactions are more often being challenged (a) with books and records actions (under DGCL § 220) and appraisal petitions in the Court of the Chancery, and (b) with claims under the federal securities laws in the federal courts.

Appraisal. Importantly, in 2017, the Delaware Supreme Court (i) strongly endorsed reliance on the merger price to determine appraised “fair value” when the sale process was “robust” (although the court declined to adopt an express judicial presumption in favor of reliance on the merger price), and (ii) definitively rejected the concept that had been articulated by the Court of Chancery that a merger price derived through an “LBO pricing model” may be inherently unreliable. Further, the Court of Chancery (i) reached below-the-merger-price results in two cases in which it relied on a DCF analysis instead of the merger price; and (ii) for the first time in decades, considered having an independent expert assist the court in understanding certain valuation issues. Based on these developments, we expect that appraisal claims will continue (at an accelerated rate) to be driven to cases involving controller transactions, MBOs, and transactions involving a flawed sale process—and there will now be fewer appraisal actions aggressively litigated through trial in non-controller transactions unless the sale process was seriously flawed.

Corwin. There has been continued broad interpretation and application of Corwin, leading to frequent dismissal of post-closing fiduciary claims against directors at the early pleading stage of litigation. Notably, for the first time since Corwin was issued in 2015, the Court of Chancery rejected application of Corwin in three cases, based on the stockholder vote having been “coerced” or not “fully informed”—but these decisions appear to highlight that Corwin “cleansing” will be inapplicable only in the case of egregious or otherwise unusual circumstances. In addition, the Court of Chancery held in one case that Corwin would not block a Section 220 demand for inspection of corporate books and records.

Controllers. MFW has provided a path to review of conflicted controller transactions under the business judgment rule rather than the more stringent “entire fairness” test when certain minority stockholder protections are in place. MFW involved a “two-sided” controller transactions (i.e., a target being acquired by its controller). The Court of Chancery has now expanded application of the MFW framework—to (i) “one-sided” controller transactions (i.e., a third party acquiring a target that has a controller that is receiving disparate consideration or a “side deal” in the merger) and (ii) transactions (including non-M&A transactions, such as a recapitalization) in which the controller receives a “unique benefit” not shared with the other stockholders.

The court also held that side deals received by a controller in a one-sided merger do not render a controller “conflicted” if they (a) only replicate the controller’s pre-merger arrangements or (b) are not material (and, therefore, business judgment rule review would apply whether or not MFW applies). In addition, the Court of Chancery continued to impose a high bar for a determination that a less than 50% stockholder is a controller. Finally, one Court of Chancery decision highlighted the risk of a redemption of preferred stock owned by a PE sponsor when the sponsor was viewed as a controller and the board did not consider the interests of the common stock; and another decision underscored that charter exculpation provisions do not apply to a defendant director in his capacity as a controlling stockholder.

Director Self-interest. The Court of Chancery reaffirmed that (i) directors receiving side benefits in a merger are not “interested” unless the benefits are material; and (ii) director “self-interest” alone, without actual self-dealing, does not establish bad faith or a breach of the duty of loyalty.

Disclosure. Post-Trulia, the traditional form of settlement of M&A litigation—i.e., minor supplemental disclosure by the target company in exchange for broad releases by the plaintiffs—has now all but disappeared in Delaware. (Notably, New York, Florida and Wisconsin have declined to adopt the Trulia approach.) In addition, Court of Chancery decisions have (i) maintained a high bar to pleading bad faith on the basis of flawed disclosure; and (ii) underscored the importance of documenting the reasons for nondisclosure of management projections. Further, (i) the SEC has provided guidance that should be helpful to defendants in rebutting a frequent allegation made by shareholder plaintiffs in federal suits challenging whether GAAP reconciliation requirements have been met; and (ii) an SEC enforcement action highlighted that negotiations with respect to white knight transactions following an unsolicited tender offer may have to be disclosed in a Schedule 14D-9 (particularly when specific pricing has been discussed). In an important ruling that opens existing director discretionary compensation equity incentive plans to possible challenge, the Delaware Supreme Court held that the stockholder ratification defense is not available with respect to such plans when a breach of fiduciary duty claim has been properly alleged.

Shareholder Activism. Notwithstanding some decline (starting in late 2016) in the assets under management, and the number of campaigns conducted, by activists, activism remained a persistent and prominent feature of the M&A landscape. Some notable trends included (i) a blurring of the lines between (a) pure activism and (b) hostile bids or private equity deals (e., more transactions had elements of both); (ii) more and quicker settlements with activists (but then institutional shareholder reaction against them, citing board support of “short-termism”); (iii) increased attention by activists to a broader range of companies; (iv) more pressure relating to board composition and removal of CEOs; (v) the emergence of more first-time activists; and (vi) more proactive preparedness by companies.

M&A Agreements. The Court of Chancery reaffirmed that (i) the precise language of merger agreements will be critical to the judicial result in contract disputes; (ii) the court generally will tend to interpret narrowly post-closing purchase price adjustment provisions; (iii) there is a very high standard for pleading fraud (leading to buyer risk when relying on an anti-fraud carve-out to an anti-reliance provision); (iv) the history of the parties’ drafting and negotiations can be evidence of their intent at the time of contracting (when extrinsic evidence is considered by the court) (and this was affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court); and (v) the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is not applicable when both parties anticipated a development that created an issue under the contract but chose to remain silent about it.

MLPs. Master limited partnership agreements typically provide for, and the Delaware courts generally uphold, the elimination of fiduciary duties to the unitholders and establish “safe harbor” procedures that bar claims even for self-dealing transactions. While some recent decisions have found an implied good faith obligation or otherwise raised the bar for general partners’ conduct, these decisions in our view are not likely to have broad effect and will be limited to atypical situations or partnership agreements with outdated terms.

Financial Advisors. The Court of Chancery reaffirmed the high bar for aiding and abetting claims; reinforced the trend of requiring expanded disclosure of financial advisor fees; and held that, if a banker’s equity stake in its client’s counterparty is disclosed in prior 13F filings, it need not also be disclosed in the proxy statement (at least when there was not an actual conflict of interest).

Antitrust and Tax. Antitrust and tax developments are not covered in this Quarterly. However, we note that the FTC and the DOJ have been more aggressive in challenging M&A transactions on antitrust grounds (including, in three cases, after the transaction had closed); that the new head of the DOJ’s antitrust division has stated that the division will cut back on “behavioral” commitments such as consent orders regulating conduct, and will instead rely more on structural changes such as divestitures, to remedy merger concerns; and that CFIUS approval of transactions has become more difficult, with the Committee more reluctant than in the past to resolve national security concerns through negotiated mitigation (particularly for transactions involving China). We note also that the tax “reform” legislation enacted in December is expected to have a significant impact on the structuring and terms of M&A transactions going forward.

Transformation in M&A Law

After three decades of evolution in the Delaware courts of an analytical framework for judicial review of board decisions relating to M&A transactions, M&A law has been transformed in the past two to three years. The decisions issued in 2017 reflect and amplify the transformation—which, as characterized by Vice Chancellor Slights (as reported in The M&A Lawyer), has involved “a narrowing of the more exacting standards of review toward business judgment deference” in M&A matters.

The following critical developments since 2014 reflect the new framework:

MFW (Del. Sup. Ct. 2014)—pursuant to which the court will now review post-closing challenges to transactions involving a conflicted controlling stockholder under the deferential business judgment rule rather than the traditionally applicable “entire fairness” test so long as certain procedural requirements are followed;

Corwin (Del. Sup. Ct. 2015)—under which post-closing actions for damages (challenging transactions not involving a controlling stockholder) are now reviewed under the business judgment rule (regardless of the standard that applied pre‑closing) so long as the transaction was approved by the stockholders in a “fully-informed” and “uncoerced” vote;

C&J Energy (Del. Sup. Ct. 2014)—which reflects greater flexibility in the standards for the process required under Revlon to fulfill the duty to seek to obtain the best price reasonably available in sale-of-the-company transactions;

Cornerstone (Del. Sup. Ct. 2015)—pursuant to which, even when the transaction at issue is subject to an entire fairness standard of review, claims against disinterested directors are dismissible at the early pleading stage of litigation unless the heightened standard for pleading a violation of the duty of loyalty or good faith (e., a breach of non‑exculpated duties) is met;

Trulia (Del. Ct. Ch. 2016)—following which significantly greater judicial scrutiny has been applied to traditional disclosure-only settlements of pre-closing M&A litigation (and they have virtually disappeared in the Delaware Court of Chancery);

Legal fees—More restrictive judicial standards for the award of legal fees in connection with bringing putative class action M&A lawsuits;

Injunctions—resistance by the courts (a) to issuing “targeted” preliminary injunctions that enjoin the specific features of transaction agreements that are viewed as problematic—with a perspective, instead, that a preliminary injunction should address the transaction as a whole and either the entire transaction should be enjoined or no injunction should issue; and (b) to enjoining transactions based on pre-closing actions brought by stockholders in a context in which the possibility of an alternative transaction was theoretical only (e., when there was no actual alternative bid available to the stockholders);

Forum selection bylaws—statutory changes permitting corporations to adopt forum selection bylaws requiring that M&A litigation be brought only in Delaware, as well as the adoption of these bylaws by many Delaware corporations; and

Other matters—the procedural consequences that have accompanied the changes in the substantive law, which have resulted in a much greater likelihood of successful motions to dismiss and limitations on or the elimination of discovery; and, although this is not a change, consistent affirmation of the remote nature of any possibility of personal liability for independent, disinterested directors due to the almost universal inclusion of exculpation provisions in company charters (which, as permitted by the Delaware statute, preclude liability for duty of care violations) and the courts’ ongoing strict interpretation of the duty of loyalty in the context of M&A transactions.

The predominant influences precipitating this transformation in the law appear to have been (i) the Delaware judiciary’s view that the rise of sophisticated institutional investors (with the ability to influence the direction of the corporations in which they invest and to determine the outcome of M&A events), combined with increased sophistication of directors, results in less need for judicial protection than was required in the past (as Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster has commented), as well as (ii) a reaction against the fact that litigation challenged virtually every M&A deal that was announced, which many viewed as reflecting an essential failure in the system.

To be sure, notwithstanding the new paradigm, there remain compelling reasons for faithful adherence by directors to a proper standard of conduct. First, liability issues aside, directors generally want to fulfill their duties to stockholders and to maintain their personal reputations for professionalism and integrity. Second, in a pre-closing action in which stockholders seek to enjoin a proposed transaction, claims of breach of fiduciary duties retain their potency in providing a foundation for judicial injunction of a transaction. Finally, Delaware law has been context-driven and the facts have been critical. Some of the emphasis on facts and circumstances no doubt has diminished as the court has moved conceptually to more black-line approaches (as evident in the MFW and Corwin decisions). But even in these cases it appeared that the factual context was critical—Did the board and special committee operate effectively? Was the proxy statement an accurate and fair description of the events and developments described? Whatever the issue that may arise in litigation, as a practical matter, albeit within a broad range, the judicial result is likely to be strongly influenced by the “atmospherics” resulting from the general approach and overall course of conduct in which the directors have engaged.

Key 2017 Delaware Decisions

Appraisal

Continued increased judicial reliance on the merger price. In determining “fair value” in cases involving third party arm’s-length mergers, the Court of Chancery has been relying primarily or exclusively on the merger price to determine “fair value” when the sale process was “robust” (Merge Healthcare, 30, and PetSmart, May 26—which reinforce Merion v. Lender Processing, Dec. 2016). The Delaware Supreme Court has now strongly endorsed this approach (although it declined to adopt an express judicial presumption in favor of reliance on the merger price) (DFC Global, Aug. 1, and Dell, Dec. 15). In DFC Global, the Supreme Court rejected the concept that extreme business uncertainty could have distorted the market for the target company and rendered the merger price unreliable. In Dell, the Supreme Court similarly expressed high confidence in the market-based merger price, even in the context of an MBO. In Dell, the Supreme Court also emphasized the problems inherent in DFC analyses. These developments (and the below-the-merger-price results discussed below) are likely to lead to a continuation (at an accelerated rate) of appraisal claims being driven to controller transactions, MBOs, and transactions involving a seriously flawed sale process.

Requirement to consider the merger price. The Delaware Supreme Court has directed that the Court of Chancery (i) consider “all relevant facts” when determining fair value and “explain” the weight accorded to each (DFC Global, Aug. 1); and (ii) consider the merger price and decide whether to accord at least some weight to it even when it is not the “best” or “most reliable” evidence of fair value (Dell, Dec. 15). We note that consideration of the merger price, and reliance on it at least to some extent if the sale process had elements of being robust, may have a depressing effect on the appraisal awards in cases in which the court previously would have relied solely on a DCF analysis.

Two below-the-merger-price decisions. Although, in the past, DCF analyses almost invariably resulted in fair value determinations above (often, significantly above) the merger price, in two cases in 2017 in which the Court of Chancery relied on a DCF analysis, the result was below the merger price (SWS Group, May 30—about 8% below; and Sprint v. Clearwire, July 21—about 56% below). In both cases, the court attributed the result to the fact that the deals were highly synergistic (as the DCF methodology does not take into account the value of expected synergies while such value was part of the merger price). We note that Clearwire has been appealed.

Potential for downward adjustment to the merger price. The Delaware courts have acknowledged that the appraisal statute mandates the exclusion from “fair value” of any value arising from the merger itself; however, the court generally has not made adjustments to exclude any such value (citing conceptual and practical difficulties relating to making these adjustments). Given that the Supreme Court did not address the issue in its two 2017 appraisal decisions, and given the Supreme Court’s general approach in viewing the merger price as the best (even if not a perfect) “proxy” for fair value when the sale process was robust, it seems unlikely that the court will now begin to make these adjustments.

Validity of reliance on the merger price in private equity transactions. The Supreme Court has now expressly and definitively rejected the concept of a “private equity carve-out” (DFC Global, Aug. 1, and Dell, 15). The concept—that a merger price derived through an “LBO pricing model” may be inherently unreliable because it is driven largely by the buyer’s required internal rate of return—had been suggested by the Court of Chancery in BMC Software (2015), Dell (2016), and Lender Processing (2016), but rejected in PetSmart, May 26.

Use of experts to assist the court. While appraisal actions have long been considered battles-of-the-experts, with dueling valuation analyses presented by petitioners and respondents, in one pending case (involving, in the petitioners’ view, a management buy-out), Chancellor Bouchard has considered engaging an independent expert to assist the court in understanding certain specialized valuation issues in the case (particularly, the plowback ratio) (Solera, oral arguments, Dec. 4). The Chancellor noted the Delaware Supreme Court’s emphasis in DFC Global on the importance of not deviating from “accepted financial principles.”

Continued reliance on DCF analyses in controller transactions. The Delaware Supreme Court affirmed (without an opinion) the Court of Chancery’s determination of fair value, based on a DCF analysis, as being more than double the merger price, in a squeeze-out merger of a parent with its wholly-owned subsidiary, which was effected at the direction of the parent’s controlling stockholder (ISN Software (2016), aff’d. 30).

Corwin

Early dismissal of claims. In cases involving stockholder-approved third party arm’s-length mergers, the Court of Chancery has continued in most cases to find that the stockholder vote was “fully informed” and “uncoerced” and, thus, to apply the business judgment rule standard of review under Corwin and to dismiss fiduciary claims at the pleading stage (Solera, Jan. 5; Merge Healthcare, Jan. 30; and Columbia Pipeline, Mar. 7—reinforcing KKR Fincl. Hldgs. (2015) (the Corwin lower court opinion) and Larkin v. Shah (2016)).

Early dismissal of claims even when directors were not independent and disinterested. Although there was ambiguity on this issue in the lower court’s Corwin opinion, the Court of Chancery has been consistent in holding that Corwin “cleansing” (e., business judgment review) is available even when the directors approving the transaction were not independent and disinterested. Notably, one case (Columbia Pipeline, Mar. 7), involved a more “vivid” duty of loyalty claim—with the court finding a valid pleadings-stage claim that the directors actually acted primarily in their own self-interest, rather than, as in past cases, the allegations being that the directors were not independent and disinterested. (We note, however, that, in another case, the Court of Chancery may have suggested some uncertainty as to whether Corwin would cleanse bad faith (MeadWestvaco, Aug. 17)). The Delaware Supreme Court still has not addressed the issue.

Corwin was found inapplicable due to the stockholder vote being “coerced.” For the first time since Corwin was decided in 2015, the Court of Chancery found (in two cases) that Corwin was not applicable because the stockholder approval of the transaction at issue had been coerced (Saba Software, Apr. 11; and Sciabacucchi v. Liberty Broadband, May 31). However, in our view, these decisions underscore that it is only in egregious circumstances that the court will find Corwin to be inapplicable due to coercion.

“Situational coercion” was found in Saba Software, where, in the court’s view, due to action by the board, the stockholders had no practical alternative but to vote for the transaction. According to the court, the stockholders were compelled to vote in favor of the merger to avoid an even worse result (continued deregistration of the company’s shares due to the board’s continued and unexplained failure to restate the company’s financial statements to reflect the board’s previous fraud). Saba raises the issue whether a vote may be deemed coerced in other types of situations where stockholders face two “bad” choices.

“Structural coercion” was found in Liberty Broadband, where the stockholder vote on an equity issuance (and voting proxy) to a corporate insider on favorable terms was tied to the stockholder vote on two proposed mergers (which were being partially financed by the equity issuance—but the board had not determined that they were required for the financing or otherwise were in the corporate interest or fair to the stockholders). According to the court, the stockholders were compelled to vote in favor of the equity arrangements in order to obtain the benefits of the mergers. Structural coercion exists, the court stated, when “the directors [create] a situation where a vote may be said to be in avoidance of a detriment created by the structure of the transaction the fiduciaries have created, rather than a free choice to accept or reject the proposition voted on.” The court inferred from the complaint that the directors had used the value of the mergers to obtain stockholder approval of the equity arrangements. The court held that the vote had no cleansing effect under Corwin, stating: “Fiduciaries cannot interlard such a vote with extraneous acts of self-dealing, and thereby use a vote driven by the net benefit of the transactions to cleanse their breach of duty.”

Corwin was found inapplicable due to the stockholder vote not being “fully informed.” For the first time that we know of, the Court of Chancery found that Corwin was inapplicable based on the stockholder approval of a transaction not having been “fully informed” (van der Fluit v. Yates, Nov. 30). In van der Fluit, the court found that the failure to identify the individuals who led the sales outreach process and negotiation of the merger was a material disclosure violation. The nondisclosure prevented the stockholders from determining the self-interest of the fiduciaries who had negotiated the deal on their behalf—in a context where the company co-founders (one of whom was also the CEO and Chair), who owned 30% of the outstanding stock, had arranged for post-merger employment for themselves and conversion of their unvested stock options. (The court also found that the two co-founders were not controllers and the court therefore did not apply entire fairness. The court dismissed the case based on finding that none of the sale process claims involved bad faith and therefore they were exculpable.)

Effect of Corwin on DGCL § 220 books and records demands. As noted, there has been a marked increase in the number of DGCL § 220 demands on public company boards. Entitlement to such inspection requires the stockholder to show a “proper purpose,” and, where the purpose is to investigate potential breach of fiduciary duties, the stockholder must show a “credible basis” for a potential breach. In one case (Salberg v. Genworth, Aug. 23), the Court of Chancery confirmed that, post-Corwin, the plaintiff in a § 220 action (seeking to investigate whether a merger properly valued the plaintiff-stockholders’ pre-existing derivative claims for purposes of maintaining derivative standing) still had to have a “credible basis” for the demand (i.e., the court would not read in a Corwin business presumption). In another case (Lavin v. West, Dec. 29), the court held that Corwin would not block the § 220 demand made to investigate a possible breach of fiduciary duties by directors relating to a stockholder-approved merger.

Uncertainty on the interaction of Corwin and Unocal. The Court of Chancery left open the issue whether, in a post-closing damages action, a defensive action taken by a board in response to a corporate threat (such as adoption of a termination fee in the merger agreement), which was approved by stockholders in a fully informed and uncoerced vote, would be subject to business judgment review under Corwin or the heightened scrutiny of Unocal (Paramount Gold and Silver, April 13). As the court found that the termination fee at issue was reasonable, it declined to address the plaintiffs’ argument that, notwithstanding the cleansing stockholder vote under Corwin, Unocal should continue to apply to the court’s review of the defensive measure. We note that the court has commented in other cases that Unocal (and Revlon) were conceived as pre-closing standards only, which suggests that the court likely would apply Corwin only (although, we note, the court recently, in van der Fluit v. Yates, Nov. 30, applied Revlon post-closing).

Controllers

MFW is applicable to “one-sided” conflicted controller transactions. MFW has provided a roadmap for business judgment review of “two-sided” controller transactions—e., transactions where the controller is buying the company it controls and is “conflicted” because it “stands on both sides of the transaction.” The Court of Chancery, in dicta (in Martha Stewart Omnimedia, Aug. 18), indicated that the court would extend MFW protection to “one-sided” conflicted controller transactions—i.e., transactions where the controller is selling its shares in a third party acquisition of the company it controls and the controller is conflicted not because it stands on both sides of the transaction but because it is obtaining a benefit in the merger that is not shared pro rata by the other shareholders. The court stated that, to obtain business judgment review under MFW in this context, the MFW-prescribed protections would have to be in place only before negotiations commenced between the controller and the buyer about the controller’s special arrangements—not, as MFW has required in two-sided controller transactions, before merger negotiations commenced between the buyer and the target company. Thus, we note, to obtain MFW protection in a one-sided controller situation involving disparate consideration or side deals for the controller, the buyer is the party that would have to act (before it commences negotiations with the controller about the arrangements with the controller) to condition the transaction on approval by a special committee and a majority of the minority stockholders.

Not all “side deals” render a controller “conflicted.” The Court of Chancery found that side deals that were not “meaningfully different” from the arrangements the controller had with the company pre-merger did not render the controller conflicted because they could not be said to have “diverted merger consideration from the other stockholders to the controller” (Martha Stewart Omnimedia, Aug. 18). The court also emphasized that the arrangements appeared to fulfill an appropriate corporate purpose of the buyer. Because there was not a conflicted controller, the court held that business judgment review applied whether or not MFW was applicable. We note that the fact in and of itself that side deals replicate pre-merger arrangements would appear to be not critical so long as what the buyer is obtaining in the side deals reflects an appropriate benefit to the company.

“Side benefits” must be “material” to invoke entire fairness. The Court of Chancery stated that, to survive a motion to dismiss, allegations that a controller received an ancillary benefit not shared by all stockholders requires that “the benefit so received was sufficiently material to overcome fiduciary duties” (RCS Creditor Trust v. Schorsch, Nov. 30). “Otherwise,” the court stated,” every business decision taken by [a controller] would be subject to entire fairness review. That is not our law.”

MFW applied to pro rata distribution of non-voting stock proposed by a controller to perpetuate its control. The Court of Chancery expanded the reach of MFW to another type of conflicted controller situation—a recapitalization, proposed by a controller, involving a pro rata distribution of non-voting equity to all of the stockholders to provide the company with currency with which to effect acquisitions without diluting the controlling stockholder’s control position (NRG Yield v. Crane, Dec. 11). Notably, the company, NRG Yield, was a so-called “yieldco” (the business model of which involves acquisitions of income-producing portfolio assets from which dividends can be distributed to the public stockholders); and the controller, NRG, managed the company and located the opportunities for its acquisitions. Due to the unexpectedly rapid pace of acquisitions by and growth of the company, NRG’s initial 65% equity interest had been reduced to 55% over just the first couple of years after the company’s IPO. The court ruled that the recapitalization was a “conflicted” controller transaction invoking entire fairness because the controller obtained the “unique benefit” (not shared with the other stockholders) of perpetuation of its control. The court distinguished Williams v. Geier (1996), in which the Delaware Supreme Court had held that a pro rata equity offering did not invoke entire fairness even though it had the effect of perpetuating a stockholder’s control. The court noted that Williams was decided based on its specific facts after a fully developed factual record. Based on that record, the Williams court (a) could assess the motives of the directors and (b) found that the board was not dominated by the alleged controller. Here, by contrast, the court stated, at the pleading stage (without evidence of board motivation), the facts alleged established that the controller proposed the recapitalization for the purpose of perpetuating its control and the controller’s control over the board was “self-evident”. The NRG Yield court then held that, even though MFW involved a squeeze-out merger, the MFW framework can be applied to non-M&A transactions as well. Finally, the court found that the minority stockholder procedural protections required for MFW to apply had been in place. The court therefore dismissed the case. The decision appears to signal that MFW provides a roadmap to business judgment review for any type of conflict situation to which entire fairness otherwise would apply. At the same time, the decision may suggest that a recapitalization involving a pro rata distribution that perpetuates a control structure, at least under certain circumstances, may be subject to the entire fairness standard unless independent director and minority stockholder approval was obtained. We note in that connection that, were entire fairness to apply, there would be substantial uncertainties as to how to determine fairness in the context of a pro rata distribution that perpetuates control.

30% stockholders acting with “a concurrence of self-interest” were not controllers. The Court of Chancery found that the two co-founders of the target who owned 30% of the outstanding stock (one of whom was the CEO and Chair) were acting with “a concurrence of self-interest” in supporting a tender offer made by an acquiror who agreed to provide them with post-merger employment and a conversion of their unvested stock options—but did not actually have control (Van Der Fluit v. Yates, Nov. 30). The court distinguished Frank v. Elgamel (2016) on the basis that the four stockholders in that case owned an aggregate of 71% of the outstanding shares. The court distinguished Cysive (2003) on the basis that the CEO-founder in that case (who owned 33% of the outstanding shares) had a “subordinate” on the board and family members who were executives at the company; and the record showed that he had actual control over the company’s operations and that his block of stock was sufficient to be the “dominant force” in a contested election.

35% stockholder was not a controller notwithstanding its statements in another context that it exercised control. The court deemed Liberty Broadband, a 35% stockholder of Charter Communications, not to be a controller even though, in letters to the SEC, in which Liberty had argued that it was not required to register as an investment advisor under the Investment Company Act of 1940, Liberty had asserted that it exercised control over Charter (Sciabacucchi v. Liberty Broadband, May 31). Liberty was not a controller, the court found, notwithstanding its statements to the SEC in another context, because it did not exercise actual control over the company—given its 35% ownership and the “contractual handcuffs” that existed (including stockholder agreement provisions that permitted it to appoint only four of ten directors and imposed standstill restrictions on it; and a charter provision that required approval of certain transactions by the stockholders not affiliated with it). (We note that in another case, Zhongpin (2014), the court found that the plaintiffs had pled sufficient facts to raise an inference that Zhu, the founder-Chairman-CEO who owned only 17% of the company, was a controller—based in part on the company’s statements in its 10-K and other public filings that he controlled the company. In that case, however, Zhu was uniquely indispensable to the company and events had unfolded to prove true that it was impossible to sell the company to anyone but his as a result.)

Potential liability for private equity sponsors and their affiliated directors when preferred stock is redeemed by a non-independent board. At the pleading stage, the Court of Chancery declined to dismiss the plaintiff’s claims of breach of fiduciary duty by the directors, and aiding and abetting by the PE sponsor, in connection with the company’s redemptions of preferred stock held by the PE sponsor (Hsu v. ODN, Apr. 25). Rather than effecting a “de facto liquidation” of the company at “seemingly fire-sale prices” and “stockpiling cash,” the court wrote, the board “could have grown [the company’s] business, gradually redeemed all of the preferred stock, and then generated returns for its common stockholders.” The court also held that the directors’ abstaining from the formal vote on the two redemptions did not necessarily shield them from liability because they had been involved in the various steps underlying the redemptions. The key distinguishing features in Hsu accounting for the court’s decision appear to be that the court deemed the preferred stockholder to be a controller; the court viewed the board as meaningfully influenced by the controller and not independent and disinterested; and, critically, the board apparently neither engaged in an adequate process to consider the interests of the common stockholders nor established a contemporaneous record indicating the bases for its decision to redeem the preferred stock.

Potential post-closing liability for controller and affiliated directors for self-tender, given a subsequent third party merger at a substantial premium to the self-tender price. The Court of Chancery, at the motion to dismiss stage, found it reasonably conceivable that a company self-tender had not been “entirely fair” given that the consideration per share paid in a third party merger two years later was three times the self-tender valuation (Buttonwood Tree Value Partners v. R.L. Polk, July 24). The court declined to dismiss fiduciary claims against the 90% shareholder family and the directors affiliated with it, noting that, while the exculpation provision in the company’s charter protected directors against liability for duty of care violations, it did not apply to a defendant in his capacity as a controlling stockholder.

Director Self-Interest

Delaware Supreme Court rejected shareholder ratification defense for discretionary compensation to directors. Reversing the Court of Chancery, the Supreme Court held that shareholder ratification of an equity incentive plan that calls for directors to grant themselves discretionary compensation cannot be used to foreclose judicial review of such discretionary actions when a breach of fiduciary duty claim has been properly alleged (Investor Bancorp, Dec. 13). The court also held that, as in this case the officer compensation was awarded at the same time as the director compensation, demand was excused as to claims that the officer compensation was excessive. Based on this decision, compensation awards under existing discretionary director compensation plans may now be subject to challenge.

Materiality requirement. In a post-closing action, the Court of Chancery found that two directors, who in connection with a merger had received “side deals” benefiting themselves, were not “interested” (Kahn v. Stern, Aug. 28). The side deals included new employment agreements, a rollover of stock, and sale bonuses. The plaintiff contended that the price reduction effected by the acquiror toward the end of the deal negotiations, from $18.75 per share down to $18.00, “appeared” to be attributable to the costs associated with these side deals—thus depriving the stockholders of consideration (with $0.11 per share attributable to the sales bonuses alone, according to the plaintiff). The court stated that, even if the argument were accepted, the plaintiff’s claim would be dismissed because the amount (and thus the materiality) of the reduction actually arising from the side deals was not pled.

Actual self-dealing requirement. The Court of Chancery stated that director self-interest standing alone, without self-dealing, is not enough to establish a breach of the duty of loyalty or bad faith (Cyan, May 11). Thus, to survive a motion to dismiss, plaintiffs must claim that a majority of the directors acted in bad faith or otherwise breached their duty of loyalty—not just that they obtained a side deal that benefitted them. In Cyan, the plaintiffs alleged that the directors, when approving a stock-for-stock merger, were motivated out of self-interest to bolster their indemnification rights (in the face of a pending securities litigation) by combining with a company with “deeper pockets.” The court noted that the directors were protected by D&O insurance; the company had cash and cash equivalents that exceeded the maximum potential damages that could result from the litigation; there were no facts pled supporting that the merger partner was in fact a “deeper pocket” than the company; and, in any event, if the company “truly lacked sufficient capital to satisfy the contractual indemnification obligations it owed to the [directors], any consideration its stockholders received in the Merger would amount to a windfall.”

Disclosure

High bar to validly pleading bad faith based on flawed disclosure. The Court of Chancery stated that the plaintiffs’ allegations of inadequate disclosure regarding directors’ new employment agreements with the private equity buyer could have supported injunctive relief in a pre-closing action—but held that, in a post-closing damages action, even material defects in disclosure are insufficient to plead a breach of fiduciary duty claim unless the allegations make it reasonably conceivable that the deficiencies resulted from the directors’ bad faith (e., that the directors knew that the disclosure was deficient and intended for it to be so)(Kahn v. Stern, Aug. 28). Referencing the company’s four pages of disclosure concerning insider interests, the court found no basis for an inference of bad faith with respect to the flawed disclosure.

Management projections that “do not exist” need not be disclosed. The Court of Chancery rejected claims challenging the failure to disclose projections utilized by the banker in valuing a company during the sale process (Saba Software, April 11). The court found that the plaintiffs failed to plead facts that showed that management projections for those years even existed. The court stated that it has consistently taken the position that “management cannot disclose projections that do not exist.” Separately, the court also observed that “the omission from a proxy statement of projections prepared by a financial advisor for a sales process rarely will give rise to an actionable disclosure claim.” We note that, in valuing a company, as a board’s (and its banker’s) determinations to utilize or not utilize, or to revise or modify, projections prepared by management can become the basis for stockholder claims of bad faith by the board, the board should carefully consider a decision to take any such action and, if taken, the reasons therefor should be documented, with a rational and legitimate business purpose articulated.

Projections not relied upon by the banker for its fairness opinion may not be material for disclosure purposes. The Court of Chancery rejected a claim that a merger proxy’s disclosures concerning management projections were deficient because the proxy only referred to Forms 10-K and 10-Q that included the relevant information that was allegedly withheld (Cyan, May 11). Separately, the court reviewed that management projections are material when they were prepared on a basis that indicates their reliability; and emphasized that projections utilized by management as an internal tool and not relied upon by the financial advisor in its fairness opinion may not meet the materiality standard. (We note, also, that if a company does only one-year-out budgets, further-out projections may or may not be reliable, depending on the assumptions utilized, the purposes for which the projections were assembled, and the nature of the company’s business.)

Developments regarding GAAP reconciliation claims. The SEC staff clarified (C&DI, Question 101.01, Oct. 17) that reconciliation to GAAP is not required with respect to non-GAAP financial measures included in projections utilized by a banker in providing a fairness opinion. The C&DI should be helpful to defendants in rebutting a frequent allegation made by shareholder plaintiffs in federal suits challenging disclosures in a proposed merger to the effect that the merging companies have failed to comply with the Regulation G GAAP reconciliation requirement for non-GAAP financial measures included in projections disclosed in Schedule 14A and Schedule 14D-9 filings. The C&DI states that “financial measures included in forecasts provided to a financial advisor and used in connection with a business combination transaction” will not be considered to non-GAAP financial measures if (i) they are provided to the banker “for the purpose of rendering an opinion that is materially related to the business combination transaction,” and (ii) the forecasts are being disclosed to comply with statutory or case law legal requirements “regarding disclosure of the financial advisor’s analyses or substantive work.” We note that two federal district courts (in Colorado and Indiana, respectively) held that failure to provide GAAP reconciliations in this context was not material (Assad v. DigitalGlobe, July 21; and Bushansky v. Remy, Aug. 16).

14D-9 obligation to disclose white knight negotiations was triggered by the target giving specific pricing indications. Allergan Inc. (Jan. 17) agreed with the SEC that it would admit to securities law violations and pay a $15 million fine for failing to disclose that it was engaged in negotiations for a possible “white knight” transaction in the months following an unsolicited tender offer. The SEC action highlights the obligation to disclose in Schedule 14D-9 merger or acquisition negotiations undertaken in response to a tender offer (including for a white knight transaction). (We note that, outside the context of the 14D-9 rules applicable to tender offers, there is generally no affirmative obligation to disclose negotiations—unless the company has made inconsistent statements that must be corrected (g., affirmative statements that the company is not engaged in discussions about a merger) or leaks about the possible transaction have occurred and are attributable to the target company.) Potentially distinguishing features in the Allergan case included that (i) after rumors about the negotiations circulated, the SEC staff had issued numerous warnings to the company that disclosure was required; (ii) specific pricing indications were given by the target to two potential white knights (and the SEC identified this as the triggering event for the obligation to disclose preliminary negotiations); and (iii) well in advance of execution of a merger agreement, there was extensive back-and-forth between the target and the ultimate white knight on price, within a relatively narrow range (which arguably suggested that significant negotiations had been underway). Notably, the lengthy duration of the company’s process (extending over many months) made leaks and rumors more likely and the extensive engagement by both the hostile bidder (and its activist shareholder backer) and the target with shareholders, in connection with proxy contests on various issues relating to the hostile bid, increased the visibility of the process to the shareholders, the market and the SEC.

Shareholder Activism

Settlement was held to be binding before execution of a definitive agreement. The Court of Chancery held that a company that had reached a “meeting of the minds” with an activist on the “essential terms” of a settlement agreement was bound and had to proceed with the purported agreement to appoint the activist’s two nominees to its board—even though the company had changed its mind about wanting to settle and a definitive agreement had not yet been executed by the parties (Sarissa v. Innoviva, Dec. 8). The court noted that the company believed that it was going to lose the proxy contest commenced by the activist and had authorized negotiation of the settlement on the terms purportedly agreed without requiring additional board approval before finalizing an agreement. (The company changed its mind about wanting to settle when it discovered just prior to the stockholder vote being finalized that a major stockholder was going to vote for the company’s slate and the activist would lose the proxy contest.) In the court’s view, the parties’ conduct manifested a mutual intention to be bound. The court noted, with respect to its review of the drafts of the settlement agreement, that the final draft proposed by the company stated that the draft was “to confirm our agreement” and had omitted the language in the previous drafts that the agreement would become effective only when a written agreement had been entered into; and that the lead negotiators had communicated to each other that “the deal is done” and all that remained was “the paperwork,” without indicating that they would not be bound until a written agreement was executed.

M&A Agreements

“Efforts” clauses require that affirmative steps be taken. The Delaware Supreme Court held that a reasonable best efforts clause in a merger agreement requires not only that the parties not take action to prevent the merger but also that they affirmatively “take all reasonable actions to complete the merger” (Williams v. ETE, Jan. 11). The Supreme Court also held that the burden was on the alleged breaching party (in this case, the acquiror, ETE) to prove that any alleged breach had not materially contributed to the failure of a condition to the merger. The Supreme Court found that ETE had not breached the agreement when its tax counsel failed to deliver a tax opinion that was a condition of closing, as the counsel had “independently” made the determination that it could not deliver the opinion (and ETE’s desire to terminate the deal had not “contributed materially” to the failure of the condition to be satisfied). Notably, Chief Justice Strine wrote a lengthy dissent—agreeing with the interpretation of the efforts covenants and burden of proof, but disagreeing with the “terse conclusion” that ETE had not influenced its tax counsel. The decision highlights (i) the risks for a party to a merger agreement associated with a closing condition for the counterparty the satisfaction of which involves action by the counterparty itself or the counterparty’s own advisor and (ii) the advisability of considering whether language should be included in a merger agreement to expressly impose an obligation on the parties to restructure a transaction to permit satisfaction of the conditions.

Public statements undermining a deal did not constitute a withdrawal or adverse change in the board recommendation—and therefore did not trigger the termination fee. Following the Delaware Supreme Court decision in Williams v. ETE (described above), Williams sought damages and ETE counterclaimed that Williams was required to pay the $1.5 billion termination fee because it had breached its obligations regarding its board’s recommendation of the merger (Williams v. ETE, Dec. 1). ETE argued that Williams had either actually or de facto withdrawn or adversely changed its recommendation of the deal by making negative comments about ETE’s CEO and failing to reconsider the recommendation in light of changes that “gutted the foundations for the original recommendation.” The court noted Williams’ “common-sense observation” that “it would be passing strange for two parties to a merger agreement to structure the agreement so that a party which desired to exit the agreement could do so, over the other party’s objections, and at the same time receive the windfall of a substantial termination fee.” The court emphasized, however, that its decision was based on finding that “the contract language, as written, [was] fatal to ETE’s contention here.” Specifically, the court stated, the “Company Board Recommendation” was defined as a recommendation to be made by a formal board resolution—and it was undisputed that the board had done so and had never formally modified or expressed any intent to modify the recommendation. While Williams’ actions conceivably could constitute a breach of its best efforts obligation, the court commented, the agreement “was careful to cabin ETE’s entitlement to the Termination Fee to those situations in which [Williams] Board action modified (or proposed to modify) the required [Recommendation], after which ETE terminated the Merger.” (Although the court let stand certain claims by ETE—that, allegedly, Williams had failed to cooperate with a $1 billion public offering that ETE planned to use to partially finance the transaction and had failed to use its best efforts to see the deal to completion—the court wrote that it was unlikely that ETE could ultimately recover damages since it was ETE that terminated the deal over Williams’ strong objection.) The decision underscores the advisability of providing that withdrawal or change of a board recommendation of a merger requires a formal board resolution (or a communication that expressly references that it constitutes a withdrawal or change of recommendation).

Working capital true-up could not be used as “end run” around contractual limitations on liability. The Delaware Supreme Court characterized a post-closing set working capital true-up as a “narrow, subordinate, and cabined remedy,” which was relevant only to changes between signing and closing, and could not be used as an end run around purchase agreement provisions that limited liability for breaches of representations and warranties (Chicago Bridge v. Westinghouse Electric, June 28). The merger agreement provided that: the buyer’s sole remedy if the seller breached its representations and warranties was a right not to close; the seller would have no liability for breaches of representations and warranties (the “Liability Bar”); and the buyer would indemnify the seller for all post-closing claims or demands against, or liabilities of, the company. The agreement also provided that any dispute over the post-closing purchase price adjustment would be submitted to an independent auditor—who was to act as an “expert” and not as an “arbitrator”; would issue a decision within 30 days in the form of a brief written statement; and would rely on the parties’ written submissions as the sole basis for the decision. The buyer contended that the seller’s post-closing net working capital calculations were flawed because the seller’s historical accounting practices in preparing the target’s financial statements were not compliant with GAAP. The seller argued that, under the purchase agreement, the buyer’s only remedy for breaches of representations and warranties had been a refusal to close (which the buyer had chosen not to do)—and that therefore the buyer could not request that the dispute-resolving auditor make a determination with respect to claims about GAAP compliance of the financial statements. Reversing the Court of Chancery decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the buyer could not pursue the historical accounting issues and could pursue only claims that were based on changes in facts and circumstances between the signing and closing. The Supreme Court emphasized that post-closing working capital true-ups are generally viewed as a “narrow remedy” and that that view was supported in this case by the business relationship between the parties, the terms of the deal (including the zero purchase price and the buyer’s assumption of the company’s liabilities), and the structure and drafting of the purchase agreement (particularly Liability Bar and the limited process and short timetable provided for dispute resolution).

Agreement did not entitle the buyer to withhold earnout payments notwithstanding suspected fraud in the information provided for the calculation of the earnout. The Court of Chancery held that, without express provisions in the merger agreement permitting it to do so, the buyer could not withhold earnout payments when it suspected that the information being provided by the former CEO of the seller (who remained with the company for almost five years after the sale as the CEO of one of the acquired subsidiaries and was the seller’s largest interest holder) was fraudulent (GreenStar v. Tutor Perini, Oct. 31). The purchase agreement provided for earnout payments during a five-year period, based on the company’s pre-tax profits in each year, calculated in accordance with GAAP. The agreement provided that, within 90 days after the end of each year, the buyer was required to prepare and deliver to the seller a calculation of pre-tax profit for the year, with the calculation becoming binding on the parties if the seller did not object to it within 30 days after delivery. If the seller objected to the calculation, the parties were required to try to resolve the dispute for 45 days, and, if they could not, they were required to engage an independent accounting firm to make the calculation, which would then be binding on the parties. After two years of making earnout payments, the buyer came to suspect that the information on which the calculation was being made was fraudulent (or, at a minimum, not in accordance with GAAP as there were material inaccuracies). The court held that the agreement clearly required any pre-tax profit calculation to be binding if not objected to by the seller within the specified time period and for disputes to be resolved by an independent accountant. The court also held that the covenant of by the buyer because there was no unanticipated development that the parties would have provided for if they could have anticipated it—instead, the parties easily could have included, but did not include, specific language in the merger agreement permitting the buyer to withhold earnout payments whenever it believed that the pre-tax profits calculation was inaccurate. The decision (i) underscores the need for (a) very specific and clear provisions with respect to the procedures that will be applicable in calculating earnout amounts and the rights of and remedies available to the parties, and (b) strict compliance by the parties with the provisions; and (ii) highlights the risk in relying on a member of the selling group who remains with the company post-sale for any information utilized to calculate earnout amounts.

Anti-reliance provision barred fraud claim notwithstanding a fraud carve-out—as the heightened pleading standard for fraud was not met. The Court of Chancery held that the merger agreement anti-reliance provision blocked claims based on extra-contractual statements except in the case of fraud and found that the heightened pleading standard for fraud was not met (Sparton v. O’Neil, Aug. 9). The court dismissed claims that the seller had induced the buyer to overpay for the target’s working capital by manipulating and falsifying invoices and financial statements before the merger agreement was signed and then, post-signing (to calculate the post-closing working capital true-up), returning the working capital amount to its actual, lower level. The seller did not dispute the buyer’s true-up calculation and proposed to release all of the funds that, under the agreement, had been escrowed for paying any post-closing liability arising from the true-up (which amount was far below the claimed liability). The court stated that the anti-reliance provision was broad and unambiguous in precluding claims based on extra-contractual statements or information provided to the buyer other than fraud; and that the merger agreement clearly provided that release of the escrowed funds was the sole and exclusive remedy for liability arising from the true-up and that there would be no liability for breaches of representations and warranties. Therefore, fraud was the only basis on which there could be liability. The court held that the plaintiffs did not plead fraud with particularity as they did not identify which invoices were incorrect and by what amount; did not establish that invoices had been “doctored” before the deal was negotiated (which would have supported their contention that the sellers’ objective was to boost the sale price); and did not identify which defendants did what actions or how any of them “assisted” in the alleged fraud (which was particularly relevant because the agreement was signed by a representative for the selling stockholders). The decision highlights the high bar for pleading fraud claims and, thus, a buyer’s risk when—based on a seller’s extra-contractual statements—agreeing to a liability cap and to an anti-reliance provision (notwithstanding a fraud carve-out being included). The decision highlights the importance to a buyer of, (i) when agreeing to an anti-reliance provision, seeking to include in the representations and warranties all material information on which it has relied in agreeing to a specified cap on the seller’s post-closing liability; and (ii) when making fraud claims, pleading with sufficient particularity (especially when the agreement is signed by a sellers’ representative).

Drafting and negotiating history can be evidence of the parties’ intent with respect to milestone payments. Based on its interpretation of a single word in a lengthy milestone payments provision of a merger agreement, the Court of Chancery held (and the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed) that the buyer did not have to make a $50 million milestone payment (SRS v. Gilead Sciences, Mar. 15, aff’d. Dec. 12). Finding that the use of the term “Indication” was ambiguous when construed within the four corners of the merger agreement,” and had multiple meanings in the oncology industry depending on the context in which it was used, the Court of Chancery relied on extrinsic evidence of the parties’ intent at the time of contracting. The court viewed the parties’ “negotiating history” as the most persuasive evidence—specifically, that the back-and-forth drafts of the merger agreements indicated that the parties had been “narrowing” the circumstances under which the milestones would be satisfied. The court thus concluded that the parties had intended to provide for milestone payments not for all regulatory approvals but only for those that would represent significant market value to the company. The court also found that emails between the parties summarizing the proposed changes reflected in the new drafts, or responding to the other party’s questions, supported this view. The Supreme Court affirmance was a 3-2 decision (with the dissenters finding that the Court of Chancery read too much into unambiguous contract language, apparently to achieve a seemingly fairer result).

Implied covenant of good faith does not apply when both parties had anticipated a development but chose not to address it. The Court of Chancery reaffirmed that the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is applied only where (i) the parties could not have anticipated a development that later occurred and (ii) it is clear what the parties would have intended if they had anticipated it (Simon-Mills v. KanAm, Mar. 30). The court confirmed that, where “unambiguous language” in an agreement is “silent” with respect to an issue, the court may consider extrinsic evidence to determine the parties’ intent at the time of contracting. In this case, the evidence showed that both parties knew of the unresolved issue at the time of contracting. The agreement, which mirrored a series of previous agreements, contained a call right that was payable in “Mills Units,” notwithstanding that, as both parties knew, Mills Units no longer existed due to a restructuring. Each party chose not to address the issue with the other, however, hoping that, when the issue arose, its own legal position would prevail. Thus, the court found that the issue had been anticipatable. Moreover, the parties’ decision to remain silent on the issue at and after signing prevented the court from concluding that they had reached a meeting of the minds as to what to do about it. The decision underscores that the implied covenant is “a limited and extraordinary legal remedy” that is “limited to a gap filling role” and is not “an equitable remedy for rebalancing economic interests after [anticipatable] events … later [affect] one party to a contract.”

MLPs

Importance of compliance by GP with MLP requirements. The court ruled that the plaintiffs’ challenge to the general partner’s issuance of convertible units to certain (but not all) unitholders, in exchange for their common units, required development of a full factual record at trial to determine (i) whether the conflicts committee approval of the issuance was effective, given that it was unclear whether a member of the committee who was allegedly not “independent” had or had not continued to serve on the committee, and (ii) whether, in any event, the issuance was a “distribution” under the partnership agreement (in which case it would have been prohibited, as the agreement required that all “distributions” be made pro rata to all the unitholders) (Energy Transfer Equity, Mar. 1). The decision highlights that GPs must be careful to ensure that a conflicts committee is comprised only of members who meet the requirements set forth in the safe harbor provision; and, if non-complying members are inadvertently included, that they are promptly removed or resign the committee and their removal or resignation is carefully documented. The court emphasized that a general partner must comply precisely with (“stay within the channel” of) safe harbor provisions for conflicts committee approval of conflicted transactions.

Application of implied good faith obligation on GP—but unlikely to have broad effect. The Delaware Supreme Court, reversing the Court of Chancery, refused to dismiss, at the pleading stage, the plaintiff MLP unitholder’s claims against a general partner that had relied on safe harbor provisions in the MLP agreement to approve a merger between the MLP and one of the general partner’s affiliates (Dieckman v. Regency, Jan. 20). The Supreme Court found that, although the MLP agreement (as is typical) disclaimed all fiduciary duties of the general partner, the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing applied to the general partner’s actions in obtaining safe harbor approvals of the conflicted transaction. In our view, the decision does not suggest that the Supreme Court intends to expand application of the implied covenant of good faith to general partners’ actions more generally. The opinion appears to be limited to establishing that the court will view a general partner as having breached the implied covenant of good faith when, as it determined in this case, the general partner engaged in “misleading or deceptive conduct” that undermined the (typically minimal) protections afforded to unitholders in an MLP agreement.

Application of entire fairness review and lower bar for good faith claims against GP—but based on atypical language in the LPA. The Delaware Supreme Court, reversing the Court of Chancery, refused to dismiss an MLP investor’s challenge to the MLP’s repurchasing an asset it had previously sold to its parent corporation (Brinckerhoff v. Enbridge, Mar. 20). The repurchase was at a significantly higher price, despite strong indications that the value of the asset had declined, and without the general partner or its banker having considered the earlier sale as a comparable transaction (notwithstanding that the limited partnership agreement safe harbor provision expressly required consideration of comparable transactions). The Supreme Court applied a standard to the general partner’s approval of the transaction that the court characterized as “equivalent to entire fairness”—but, importantly, the ruling was based on the court’s interpretation of the particular, atypical language in the limited partnership agreement (particularly, the unusual express requirement that comparable transactions be considered—which the general partner and it banker did not do). The Supreme Court also made other important rulings and statements, including: (i) stating that it was “changing course” from previous holdings and applying a higher standard in connection with the pleading standard for bad faith by a general partner (in the context of the availability of exculpation); (ii) raising questions as to whether an LPA’s conclusive presumption of good faith based on reliance on a fairness opinion could be undermined due to the timing of and substantive weaknesses in the opinion; and (iii) stating that equitable remedies (such as reformation or rescission of the challenged transaction) could be available to redress general partner breaches made while acting in good faith. However, in our view, all of these flowed from the court’s imposition of an entire fairness-like standard and/or its finding, based on that standard, that a valid claim of breach by the general partner had been made. Accordingly, we think it unlikely that the decision will impact partnerships that operate under more typical agreements (where such a standard would not be imposed and it would be much more difficult for a plaintiff to state a valid claim of breach). The decision is notable for (i) underscoring that the particular language of the partnership agreement at issue is critical to the judicial result in MLP cases generally—and MLPs operating under older-form agreements may want to consider adding a state-of-the-art “safe harbor” for conflict transactions if possible; and (ii) the court’s questioning whether a company could reasonably rely on a fairness opinion when the banker had not considered a recent transaction for the very same assets (at least when the partnership agreement expressly required that comparable transactions be considered).

Financial Advisors

Passive failure of banker to ensure adequate disclosure does not support an aiding and abetting claim. The Court of Chancery dismissed aiding and abetting claims against the target company’s investment banker (and the target’s legal counsel) that were based on their alleged knowledge of material disclosure omissions in the company’s proxy statement and their failure to act to have them corrected (Buttonwood Tree Value Partners v. R.L. Polk, July 24). Even if the banker knew that there was mal-disclosure, the court stated, there were no facts alleged indicating that the banker’s failure to take steps to correct these omissions resulted in “knowing participation” in the alleged breach. The court wrote: “The Plaintiffs allege only a passive awareness on the part of a non-fiduciary of the omission of material facts in disclosures to the stockholders, made by fiduciaries who themselves were aware of the information” (emphasis by the court). There was no allegation, the court stated, that the banker had “worked a fraud on the directors, or otherwise caused misrepresentations by withholding information from fiduciaries.” The court concluded: “Passive failure on the part of third parties to ensure adequate disclosure to stockholders, without more, cannot support an inference of scienter or knowing participation” (emphasis by the court) in any breach resulting from the failure to disclose facts.

No aiding and abetting if no underlying breach by directors. The Court of Chancery confirmed (and the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed) that claims made against a financial advisor for having aided and abetted directors’ breach of fiduciary duties “may be summarily dismissed based on the failure of the breach of fiduciary duty claim against the director defendants” (Volcano (2016), aff’d. Feb 9). In other words, there can be no liability for aiding and abetting a breach that did not occur. At the same time, however, we note that, in the limited context in which aiding and abetting liability may apply, the court can find the banker liable for aiding and abetting a breach by directors even under circumstances where the directors themselves face no liability for the breach (because, for example, the directors have settled, or have been dismissed from the case because the claims against them are for exculpable offenses) (Rural Metro (2016) and see Good Technology below).

Failure to quantify banker’s fee for financing led to injunction. The Court of Chancery ordered postponement of the stockholder vote on a company’s planned acquisition pending corrective disclosure being made to specify the amount of the financial advisor’s fee for providing part of the financing for the acquisition (Vento v. Curry, Mar. 22). The disclosure had been only that the advisor “will receive additional fees” for providing a portion of the financing. The court noted that (a) the defendants did not seriously dispute the materiality of the financing fees the advisor might become entitled to as a result of the merger and (b) the relevant fees were quantifiable. The defendants argued that the stockholders could deduce the amount of the fee from the registration statement and a previously filed Form 8-K, but the court explained that “buried facts” are inadequate (and particularly so in respect of banker fees disclosure). “One reasonably would expect that all material facts concerning a financial advisor’s potential conflicts of interest would be disclosed in plain English in one place…,” the court wrote.

SEC enforcement actions emphasized disclosure of the circumstances under which banker fees were to be paid. The SEC rules require that a Schedule 14D-9 include “a summary of all … arrangement[s] for compensation” with all persons who have been retained to assist the issuer in making a solicitation or recommendation with respect to a tender offer received by the company. SEC guidance (in the form of a C&DI issued Nov. 2016) clarified that generic disclosure that a banker is entitled to “customary fees” will usually constitute insufficient disclosure. The SEC entered into a Cease-and-Desist Order with CVR Energy (Feb. 14) in connection with CVR’s disclosure that it had agreed to pay “customary compensation” to two banks retained for advice in connection with a hostile offer the company had received. The engagement letter provided for payment of a $9 million fee if the company remained independent; a $4 million “discretionary fee” (bonus payment) at the discretion of the board; a $6 million fee if a transaction were announced; and a “sales fee” (success fee) equal to 0.525% of the aggregate consideration payable in the event of any sale of the company (whether to the hostile bidder or not and whatever the consideration). The SEC found that the success fee was “expansive” and “not customary” in the context of a hostile tender offer; and that the stockholders were unaware of the potential conflicts of interest posed by the fee arrangements because there was no disclosure that the success fee was payable even if the hostile bidder acquired the company and irrespective of the consideration to be received by the stockholders.

Specification of the services provided by the banker was not required. The Court of Chancery found it sufficient that a proxy statement disclosed that, in the previous two years, the banker had provided “financing services” to an affiliate of its client’s counterparty, for which it had received “customary fees of approximately $1 million”—without specifying the affiliate, the services or the exact fees for the services rendered (Saba Software, Apr. 11). “What was material, and disclosed, was the prior working relationship and the amount of fees,” the court wrote.

Disclosure of the reasons for an increased fee to the banker was not required. The Court of Chancery found the proxy statement disclosure sufficient notwithstanding that the reason for the company agreeing to the banker’s request for an increased fee was not disclosed (Paramount Silver and Gold, Apr. 13). The banker had requested the additional fee because, in addition to its other activities relating to a merger, the banker obtained funding for a $10 million cash infusion to company that was being spun off and secured a royalty agreement under which the company would receive $5.5 million—neither of which had been contemplated at the time the initial engagement letter was entered into. “Because the Registration Statement disclosed the total amount and the contingent share of [the banker]’s compensation in connection with the merger, [the] stockholders were made aware of the full magnitude and nature of [the banker]’s financial interest in the transaction… [and how the board and the banker] negotiated to arrive at the fully disclosed final fee arrangement is immaterial,” the court wrote.

Disclosure of the banker’s equity ownership in prior 13Fs was sufficient. The Court of Chancery reiterated that, because of the central role that bankers play in the evaluation, selection and implementation of M&A transactions, the law requires “full disclosure of investment banker compensation and potential conflicts”—however, the court noted, the Delaware Supreme Court provided in Micromet (2012) that “disclosure [of equity ownership in the client’s merger counterparty] in a Schedule 13F is sufficient, particularly where the balance of the investment adviser’s ownership does not create an economic conflict” (Columbia Pipeline, Mar.7). We note that, in both decisions, the court recognized that the financial advisor held a greater stake in its client than in the client’s counterparty and therefore the banker did not have an actual conflict; and, moreover, in Columbia Pipeline, first, the banker’s “ownership” of the shares at issue reflected only an ability to vote and manage the shares, not a true economic interest in the shares, and, second, in any event, as a practical matter, the banker’s interest in the advisory fee it was to receive would have dwarfed its interest in the buyer’s shares or the target’s shares.