Lisa Andersson is Head of Research of Aktis and Stilpon Nestor is Managing Director and Senior Advisor at Nestor Advisors. This post is based on their recent Nestor Advisors/Aktis publication.

This summer marked the 10-year anniversary of the start of the global financial crisis. Over the 18 months following August 2007, several bank collapses in the United States, Germany and Britain, culminating with the demise of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 shook the financial system to its core. The interconnectivity of the world’s financial system meant that the repercussions would be felt globally, and on a monumental scale. The US Department of the Treasury has estimated that total household wealth would lose some $19.2 trillion following a publicly-funded government bailout program. Over the last decade governments, regulators, banks and their investors have revamped the financial system and its supervision in order to recover the public subsidy and prevent a similar crash from happening again.

In Europe, politicians and regulators at both the national and European level abandoned the path of deregulation and dramatically increased regulatory requirements and the scope of prudential supervision with an unparalleled focus on governance. The Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) and the ensuing European Banking Authority (EBA) and European Central Bank (ECB) guidance implied stricter suitability reviews for board members and senior management, along with individual responsibility and in some cases criminal liability of non-executive directors (“NEDs”), as well as strict limits on variable remuneration. Higher regulatory requirements were compounded by the creation of a single supervisor for all systemic Eurozone banks. In many countries, especially the smaller ones, familiarity with supervisors usually allow a larger margin of forbearance and greater tolerance in assuming local sovereign risk. This has since disappeared. New rules and stricter oversight practices in the financial industry have translated into higher governance requirements and expectations for European banks’ boards of directors and senior management. So how do the boards and management committees of the top European banks measure up to their former selves? Data from the 25 largest listed banks [1] in Europe shows that boards today are smaller, work harder, and have a higher level of expertise than a decade ago.

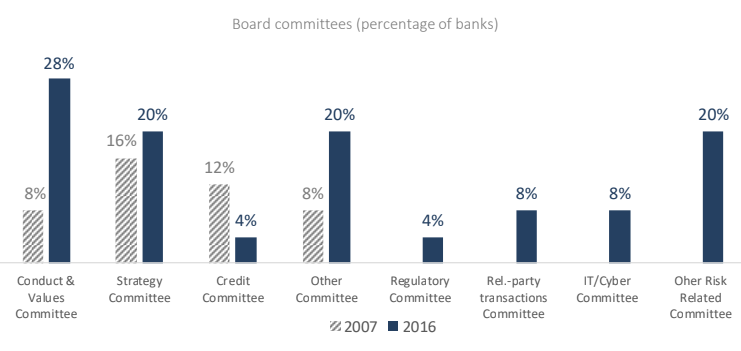

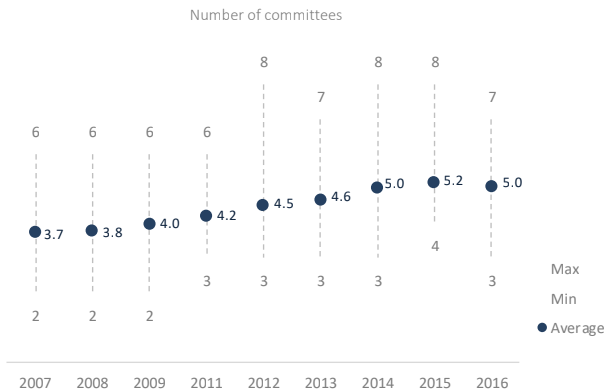

While board sizes are getting smaller, the number of committees supporting the board has consistently grown over the years. This is in part driven by the mandatory separation of the audit and risk committee into two separate committees, but also by a general trend towards establishing more and more committees focusing on regulatory and compliance issues, as well as bank culture, conduct and reputation.

On average, 86% of board membership has been refreshed post-crisis. New board members brought with them greater independence, banking experience and general financial expertise among NEDs, as well as an improved gender balance on the board. In fact, women now comprise on average 34% of top European banks’ board membership, a development largely driven by national initiatives. Another significant change since 2007 is the fact that all the bank boards in the group now conduct regular assessments of the effectiveness of the board, a Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) requirement. The disclosure of this process has also improved significantly, with 48% of banks now disclosing specific challenges identified and actions taken to address these.

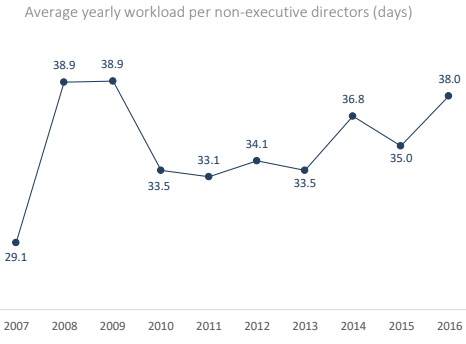

The role of a bank NED has evolved post-crisis. With increased scrutiny, boards of financial institutions are now required to adopt a more hands-on approach, requiring a greater time-commitment by their non-executive directors. On average, the workload per director has increased by over 30% compared to pre-crisis levels.

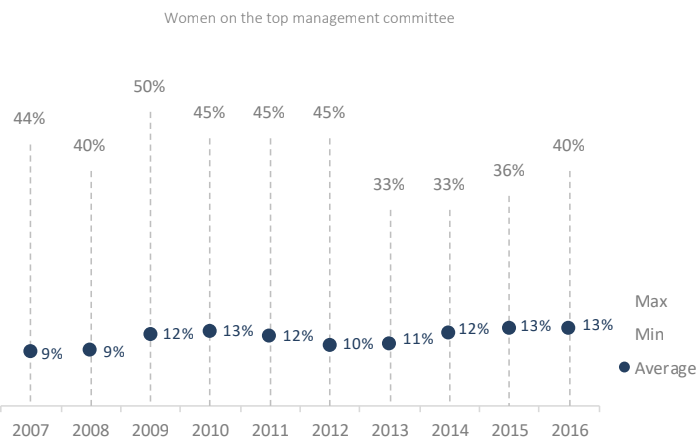

In contrast to the board, the size of management committees has grown in recent years. The top management committee now tend to include more heads of functions, reflected by the increased presence of the Chief Risk Officer, Head of Compliance and Head of Legal. Despite the positive development of a better gender balance on the board of directors, the number of women on the highest management committee has not increased significantly over the last ten years. This may suggest that the “top-down” approach of board quotas adopted in many European countries might be less than effective in promoting gender equality.

Size

The boards of the top European banks have been slimmed down since the crisis. The average size of the board is now 14, and only four of the top 25 banks had a board consisting of 20 members or more in 2016. In addition, the spread between the largest board and the smallest board has narrowed since 2007.

Smaller boards are generally considered to be more cohesive and could serve to encourage a more active dialogue among board members. In order to facilitate this, bigger boards segment their work into more committees. We note that the larger boards in the group (14 members or more) have on average one additional committee compared to the smaller size boards. Overall, the number of committees has been steadily increasing. The separation of the Audit and Risk committee required by the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) has contributed to this development, as has the creation of new, specialised committees.

Board refreshment and tenure

European banks have changed their boards significantly since the crisis. On average, only 14% of current board members have been sitting on the board since before 2008.

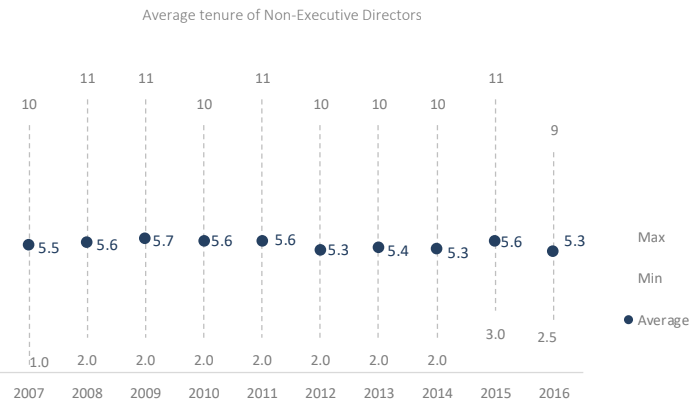

While the average tenure of NEDs has remained at a similar level since 2007, more and more banks now disclose specific term limits for directors. As can be seen on the following pages, the appointment of new members has resulted in an increase in independence, diversity and financial expertise of the board.

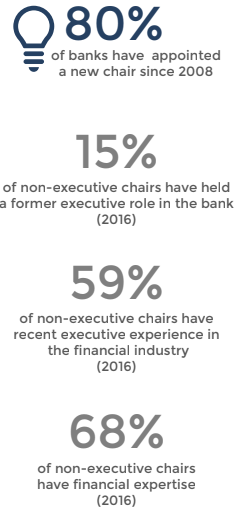

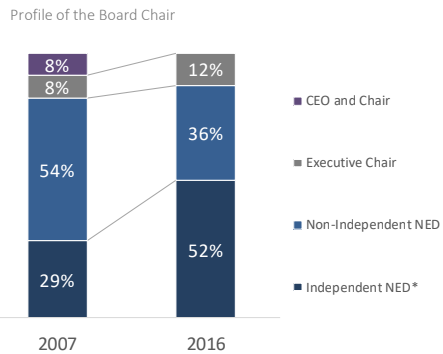

Profile of the Board Chair

The profile of the board chair has also evolved post-crisis. Compared to 2007, more and more chairs are now independent non-executives (independent or independent on appointment), 12% are executive chairs, while 15% of the non-executive chairs have previously held an executive responsibility in the bank.

The profile of the board chair has also evolved post-crisis. Compared to 2007, more and more chairs are now independent non-executives (independent or independent on appointment), 12% are executive chairs, while 15% of the non-executive chairs have previously held an executive responsibility in the bank.

Many non-executive chairs have financial expertise, and 59% have held a senior executive role within the financial industry within the past 10 years.

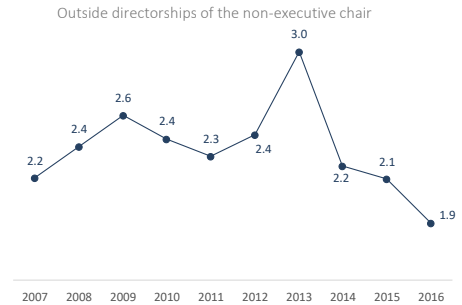

As is the case for the rest of the board, the workload and time commitment of the board chair has increased significantly in recent years. As a result, the number of external directorships held by the non-executive board chair has decreased, and only a very small minority (9%) holds an external executive position in addition to their board responsibilities

Diversity

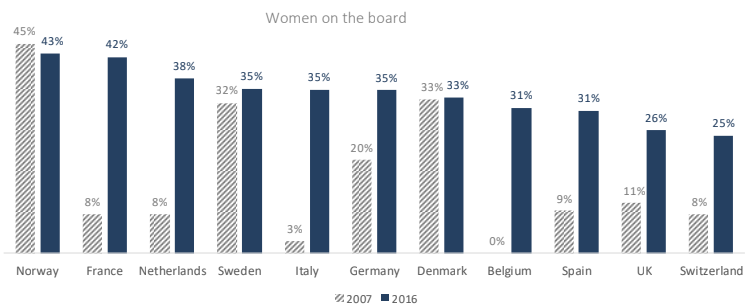

European countries have adopted different initiatives to encourage gender diversity. These initiatives include reserved quotas for women at board level, voluntary targets, and public disclosure of succession planning that targets a better gender balance on the board.

As a result, gender balance at board level has improved significantly, with the average percentage of women on the board having doubled since before the financial crisis (from 15% in 2007 to 34% in 2016. In addition to increased gender diversity, the presence of international members on the board has also grown, from 20% in 2007 to 25% in 2016.

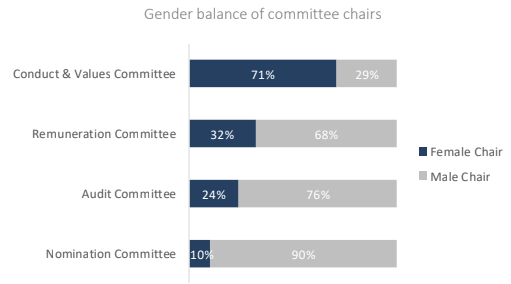

In terms of committees, there are fewer women chairing Nominations committees, while the majority of conduct and values committees have a female chairperson.

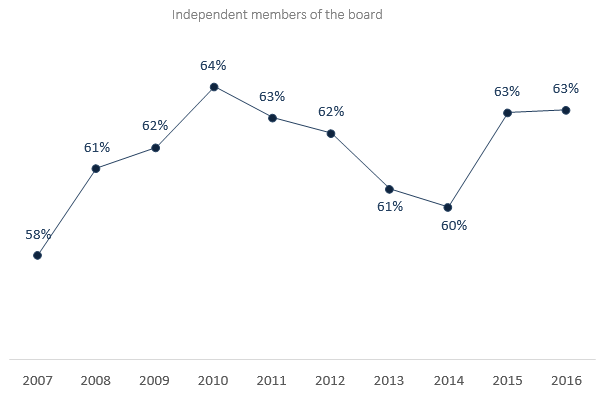

Independence

A majority of independent directors [2] on the board has largely been regarded as international best practice and key to fostering critical discussions as well as adequate challenge of management. It is therefore not surprising that independence on the board has continued to rise, and on average, 63% of boards are now comprised of independent members. In addition to independence, the skills profile of board members has been subject to greater scrutiny by both supervisors and investors. Bank boards are now expected to collectively have industry-specific knowledge and expertise as well as hands-on experience in risk management in order to be able to fulfil their role in the areas of strategy and risk management.

NED Background and Experience

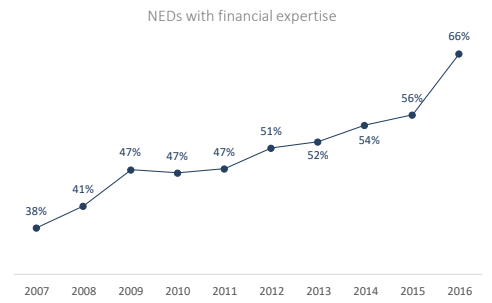

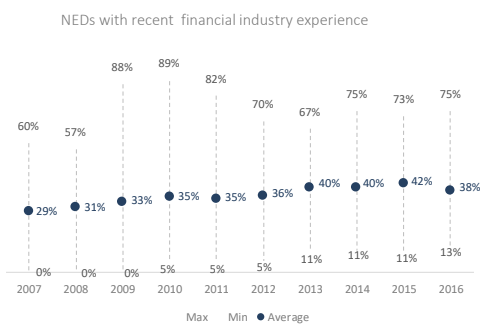

Our analysis shows that the number of NEDs with financial expertise (SOX definition) [3] is on the rise, as is the number of those with recent financial industry experience (i.e. have occupied a senior executive position in a financial institution within the past 10 years).

All of the top European banks now have at least one non-executive director on the board with recent financial industry experience, which was not the case between 2007–2009. In addition, 44% now include at least one NED on the board who has held a recent senior risk management position.

Committees Supporting the Board

Following the crisis, the increased supervisory focus on the role of the board has caused a growing number of European banks to establish separate committees to address specific areas of concern. Considering the growing workload of the board of directors (see page 12), the in-depth analysis of some matters may be more conveniently delegated to specific committees as to streamline meetings of the full board.

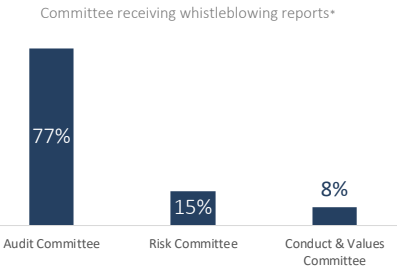

Given the reputational and financial damage caused by alleged acts of misconduct among some of the European banks included in this chapter, it may not be surprising to find that many boards now have established separate committees dealing exclusively with conduct, compliance or regulatory matters.

While only two out of the 25 banks had a separate committee overseeing conduct, culture and values prior to the crisis, this is now the case for 28%, or seven, of the top European banks.

Only two of the top European banks have established a board committee focusing specifically on technology and cybersecurity. This is a practice that has become increasingly common in the United States (50% of the American Global Systemically Important Banks (“GSIB-s”) have established a special board committee overseeing IT and cyber related issues), but remains relatively uncommon amongst European banks. However, 86% of the top European banks include in their 2016 disclosures that the board examined issues related to cyber risk and security during the year.

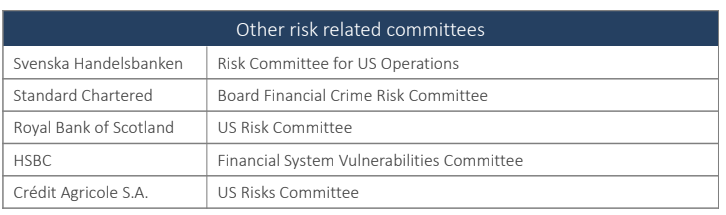

In 2016, five banks had also established an additional risk related committee. Among these are risk committees overseeing US operations, now required for non-US banks with significant US activities following enhanced prudential standards.

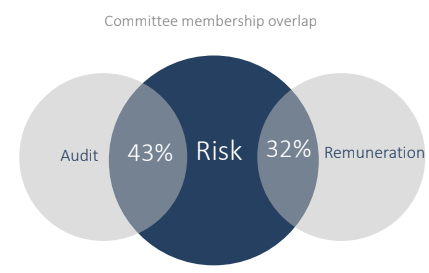

Since risk-related matters are inevitably considered by board committees in addition to the risk committee, it is important to co-ordinate the input committees provide to the full board. To this end, committee cross-membership is a commonly adopted solution. On average, 43% of risk committee members also sit on the audit committee, and 32% are also members of the remuneration committee.

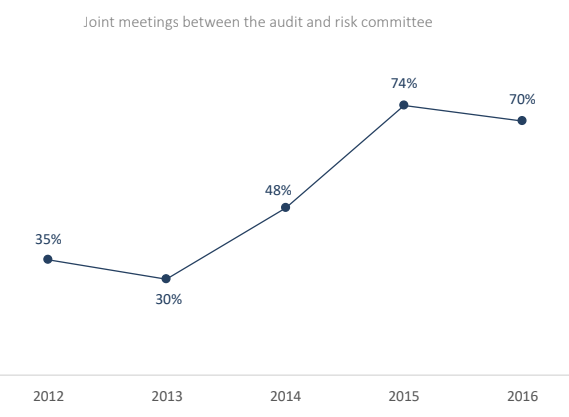

Another practice that is becoming more common is the organisation of joint meetings between the audit committee and the risk committee. In 2016 70% of banks disclosed having such meetings, compared to only 35% in 2012.

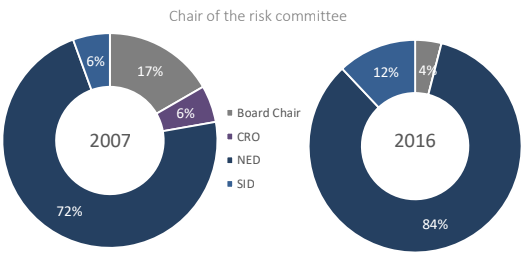

The role and profile of the risk committee has also evolved post-crisis. The chair of the committee is now always a non-executive director, and in 12% of cases this role is filled by the Senior Independent Director. In 2007, 17% of risk committees were chaired by the board chair, while in 2016 this is the case in only one bank.

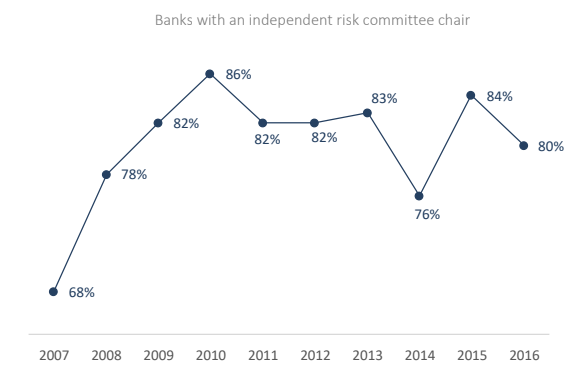

The majority of risk committee chairs are now independent, 64% have had an executive role in a financial institution during the last 10 years, and over two thirds have financial expertise. This development closely follows the profile of committee membership, where the level of financial expertise has increased to an average of 70% in 2016.

Workload and Time Commitment

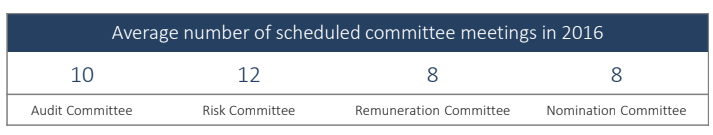

Boards are considerably busier today than before the crisis, with the average workload [4] of a NED in 2016 now at a similar level to the mid-crisis peak of 2008-2009. While there are significant differences among the European banks in terms of the number of board meetings held during the year, the average has increased from 11.5 meetings held in 2007, to nearly 14 in 2016

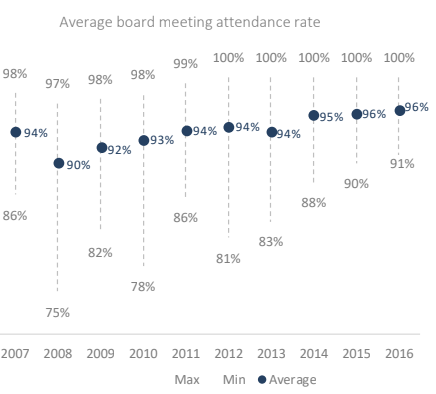

The increased number of board and committee meetings has also been accompanied by a higher attendance rate at meetings. While the average has remained relatively steady since 2007, rates has gone up across all banks—and in 2016 the minimum attendance was at 91%.

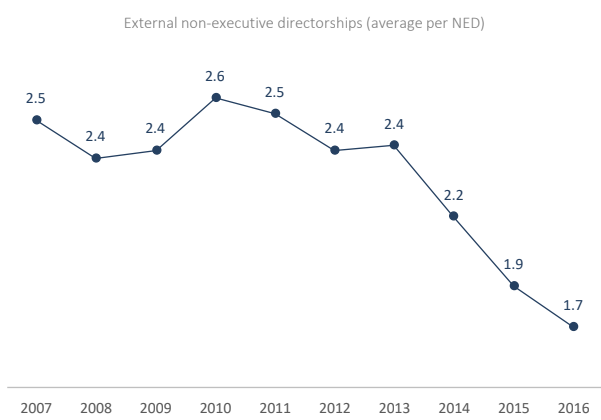

Given the increased workload required by bank board members, it is not surprising that the number of external time commitments of non-executive directors has fallen since 2007. Such commitments have also been curbed by the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV), limiting the number of outside commitments to one executive directorship with two non-executive directorships, or a maximum of four non-executive directorships at the same time. While the number of external non- executive directorships [5] among NEDs has decreased since 2007, 33% of NEDs of the top European banks still hold a full time executive position [6] in addition to their board duties.

Board Remuneration

In most jurisdictions, the role of a bank NED requires greater time commitment and the acceptance of a higher level of personal liability than before the financial crisis. During this period, the average total remuneration of non-executive directors has been trending upwards, having increased by 60% since 2007. However, this has closely followed an increase in time commitment, and the “pay per day” for the average NED has remained at a similar level since 2007, with only a 22% increase over the last 10 years.

The total remuneration of the non-executive board chair [7] has not increased by any significant amount over the last 8 years, considering the increase in workload. In 2016, figures are still 15% below the pre-crisis levels of remuneration. For the majority of European banks NED remuneration is based on a fixed fee, irrespective of the number of meetings. There are however exceptions, where the compensation structure includes a set annual emolument component, as well as an attendance fee for each meeting of the board and committees.

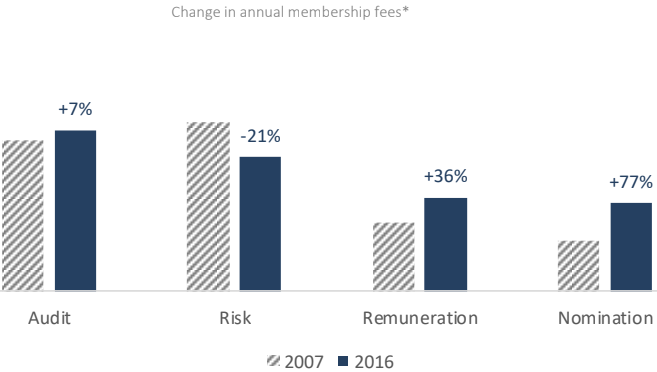

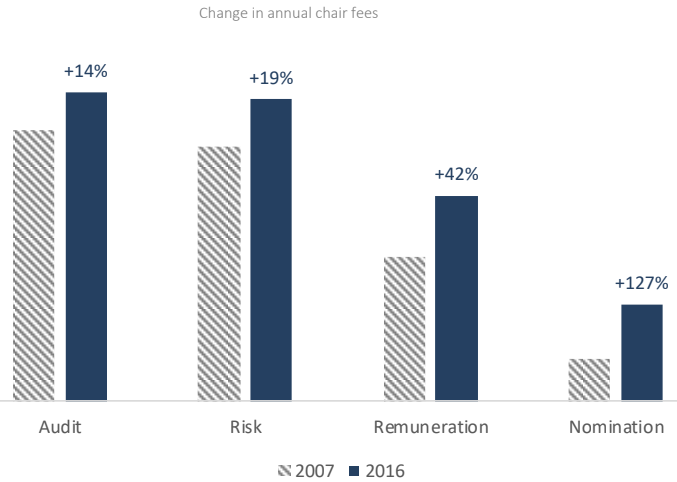

As noted earlier, a considerable amount of work is now delegated to a growing number of committees. With the exception of the risk committee, fees for those serving on these committees has increased since 2007.

In the case of the nomination committee, chair fees have more than doubled since 2007. The chair of the risk and audit committees receive the highest fees for their service, perhaps not surprising given the higher number of meetings, and the complexity and urgency of the matters discussed in such committees.

Evolution of the Top Management Committee

Extensive changes have been made at the top management level since the crisis. Since 2007, 92% of the top European banks have replaced their CEO at least once, and in 44% of cases more than once. More often, in 56% of cases, the CEO appointed has been promoted through the ranks of the bank, what we define as an insider. [8]

While boards are getting smaller, top management committees have continued to expand in size, from an average of 9 members in 2007 to nearly 13 in 2016.

The composition of the top management committee has also changed considerably since the crisis. Risk-related failures contributing to the cause of the crisis and the misconduct scandals that followed have driven changes in control functions and the composition of management committees. Chief Risk Officers are now always a member of such bodies (while this was the case in only 55% of banks in 2007). Heads of Legal (or General Counsel), as well has the Head of HR are also increasing in numbers.

Given the importance of the risk management role within financial institutions, it is however worth noting that the number of top management committee members that have previous executive experience within risk management or internal audit remains relatively low. In addition to the CRO and Head of Internal Audit, the members of the top management committee that most frequently have risk specific experience are the Head of Compliance, the Chief Financial Officer or the Chief Operating Officer (COO).

Despite the changes among top leadership teams, women are still underrepresented among top managers. In 2016, four banks still had no women on their top management committee. In 2007, this was the case for twelve of the banks in the group.

The cultural significance of a gender balance at board level, in setting the “tone at the top”, is often highlighted. However, having more women on the board does not necessarily mean more female executive leaders. In fact, while the number of women on the board has doubled from 15% to 34% since 2007, the average percentage of women on the executive committee only grew from 9% to 13% during the same period of time.

Board Evaluation

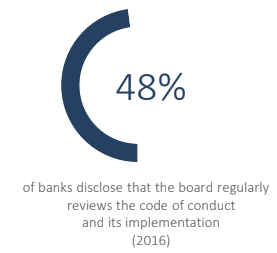

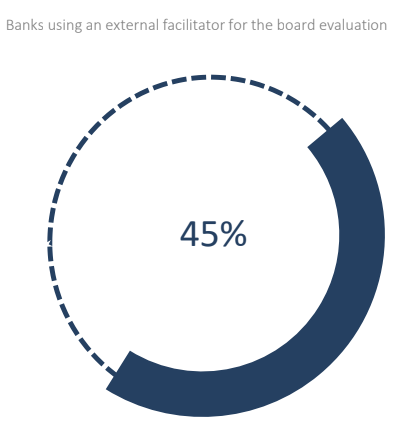

To ensure board effectiveness, all the top European banks now conduct regular assessments of the effectiveness, composition and functioning of the board. This is a practice encouraged by all European regulators and a requirement of the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV).

In 2016, all of the 25 European banks surveyed conducted an annual self-evaluation. Of these, 45% disclose that they retain an external advisor to facilitate this evaluation.

In recent years, codes of corporate governance and institutional shareholders have begun to demand better disclosure in matters related to the board evaluation process. These include how evaluations are conducted, who conducts them, and the actions taken to identify challenges. In 2016, 68% of banks disclosed key action points resulting from the evaluation, and 28% disclosed the name of the external facilitator conducting the review.

Endnotes

1Measured by market cap as of September 2017. The analysis draws upon public disclosures, including annual reports, articles of association, corporate governance reports, regulatory filings, terms of reference of board committees, board and management regulations, press releases and company websites. The data typically shown is reviewed for the period 31 December 2007 to 31 December 2016.

The following 25 banks are included in our analysis: Banco Santander SA, Barclays Plc, BNP Paribas, Caixabank, Crédit Agricole S.A., Credit Suisse Group AG, Danske Bank Group, Deutsche Bank AG, DnB Group, HSBC, ING Bank N.V, Intesa Sanpaolo, KBC Group, Lloyds Banking Group PLC, Natixis SA, Nordea Bank AB, Royal Bank of Scotland, Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, Société Générale, Standard Chartered, Svenska Handelsbanken, Swedbank, UBS AG, UniCredit SpA and Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria S.A.

(go back)

2A director is considered independent if he/she is disclosed so by the company. This includes board chairs that are considered independent on appointment. In countries where independence is defined according to more than one code/listing rule/regulation, we consider a director independent when identified as such according to all applicable definitions.(go back)

3A non-executive director can be considered a “financial expert” according to the SEC implementation of the Sarbanes- Oxley Act definition: “Under the final rules, a person must have acquired such attributes through any one or more of the following: (1) Education and experience as a principal financial officer, principal accounting officer, controller, public accountant or auditor or experience in one or more positions that involve the performance of similar functions; (2) Experience actively supervising a principal financial officer, principal accounting officer, controller, public accountant, auditor or person performing similar functions; (3) Experience overseeing or assessing the performance of companies or public accountants with respect to the preparation, auditing or evaluation of financial statements; or (4) Other relevant experience.”(go back)

4Our workload estimate adopts the same assumptions across all peers unless otherwise disclosed by the banks themselves. We estimate the duration of committee/board meetings and the time needed to prepare for such meetings.(go back)

5Refers to all non-executive positions held outside the group in for-profit corporate entities. This definition excludes non-profit organizations, subsidiaries, investment trusts, charities, advisory boards and other advisory positions, trade associations, governmental positions, and universities/museums/art galleries.(go back)

6Refers to all executive positions held outside the group as well as other full-time positions such as Member of Parliament. This definition excludes charities, foundations, advisory or university positions.(go back)

7Includes any fixed and variable remuneration, additional fees for serving on board committees, benefits and all other remuneration expensed to the chair.

*The decrease of risk committee fees is largely driven by two of the banks in the group, Banco Santander and Intesa SanPaolo. In the case of Santander, the executive risk committee of the board was disbanded in 2015 and a new risk supervision, regulation and compliance committee was created, resulting in a reduction of average fees.(go back)

8An executive is considered an insider if he/she has spent 10 or more years at the current company in one or more positions.(go back)

Print

Print