Barbara Novick is Vice Chairman, Michelle Edkins is Global Head of Investment Stewardship, and Tom Clark is Head of Global Public Policy, Americas, at BlackRock, Inc. This post is based on a BlackRock memorandum by Ms. Novick, Ms. Edkins, Mr. Clark, and Alexis Rosenblum.

Your company’s strategy must articulate a path to achieve financial performance. To sustain that performance, however, you must also understand the societal impact of your business as well as the ways that broad, structural trends –from slow wage growth to rising automation to climate change –affect your potential for growth.

—Larry Fink, BlackRock, Annual Letter to CEOs, January 2018

Investors are increasingly turning to convenient, low-cost investment solutions such as index funds to help save for retirement and other important financial goals. This trend has fueled the growth of the asset management industry and led to questions around what impact, if any, asset managers should have on the companies they invest in. How do asset managers approach investment stewardship and to what degree do they factor in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations?

For BlackRock, the answers are inseparable from our role as a fiduciary to our clients’ assets. Our mission is to create a better financial future for our clients and our number one focus is on generating long-term sustainable performance. Just as we expect the companies in which we invest to understand the macroeconomic and industry trends in which they operate, we also believe that a company’s awareness of regulatory and societal trends helps drive long-term performance and mitigate risk.

In this post, we review the roles of the stakeholders in the investment stewardship ecosystem, including asset managers, asset owners, index providers, and proxy advisors. We then explore the different approaches to investment stewardship, including BlackRock’s engagement-first approach. Our overarching goal is to encourage companies to deliver long-term, sustainable growth and returns for our clients. In addition, we highlight publicly available data on the voting records of US-registered mutual funds, which demonstrate considerable variability in voting patterns among asset managers. At BlackRock, we take an engagement-first approach where proxy voting is only one component of our process. We focus primarily on the US corporate governance landscape, but similar practices exist globally.

Key Observations

- The roles and responsibilities of asset owners, asset managers, index providers, and proxy advisors are often conflated in discussions around investment stewardship.

- Asset owners are the economic owners of assets. They make critical decisions about how their money is invested, including:

- Establishing investment policies (e.g., investment objectives, asset allocation policies, and approach to sustainability, or ESG matters).

- Whether to manage their assets internally or outsource to an external asset manager.

- How to handle their responsibilities as public company shareholders (e.g., proxy voting policies, reliance on proxy advisors, and/or insourcing versus outsourcing of investment stewardship activities).

- Asset managers are fiduciary agents, required to act in the best interest of their clients, the asset owners.

- There are many different business models of asset management, with companies offering a wide range of products to meet the needs of various clients.

- Likewise, there is a wide range of approaches to investment stewardship across the asset management industry.

- Asset managers do [not]{.underline} participate directly in the economic results of companies in which they invest on behalf of clients.

- Traditional asset managers (e.g., mutual fund managers) generally do not take seats on public company boards.

- Index providers develop index construction rules that drive the inclusion of securities in indexes.

- Index providers offer both broad market and specialized indexes.

- Index providers have developed indexes that exclude certain exposures (e.g., tobacco, controversial weapons) as well as suites of ESG-oriented indexes in response to demand from asset owners.

- ESG indexes have their own specific index inclusion (or exclusion) rules.

- Proxy advisory firms provide data, voting recommendations, and vote submission technology to their clients, who may use all or just some of the available services.

- Investment stewardship encompasses engagement with companies and the voting of proxies.

- Investors (inclusive of asset owners and asset managers) approach investment stewardship in different ways. Some rely heavily on proxy advisor recommendations, while others emphasize various forms of engagement.

- In line with our fiduciary responsibility, BlackRock’s number one focus is on generating long-term sustainable performance for our clients.

- BlackRock takes an engagement-first approach to investment stewardship, emphasizing direct dialogues with companies on issues that we believe have a material impact on financial performance.

- BlackRock has never initiated a shareholder proposal on any company’s proxy statement, initiated a proxy fight, or led an activist effort against management; and BlackRock has never sought a seat on a public company board as part of its stewardship activities.

- BlackRock is committed to providing transparency. Our engagement priorities, voting guidelines, and voting records are available on our website.

- Proxy Voting Data

- Proxy voting statistics include both management proposals and shareholder proposals. In 2017, there were nearly 28,000 ballot items on proxies of Russell 3000 companies, of which more than 27,000 were management proposals, the majority of which are routine.

- Asset managers can and do take different views on the same proposal.

- All equity assets managed by BlackRock may not be voted the same way on any given issue.

- Any decision about a company’s strategic direction is up to the company’s management, its board, and the majority of shareholders.

Roles of Key Stakeholders

Who are the relevant stakeholders in the investment stewardship ecosystem? Asset owners, asset managers, index providers, and proxy advisors each play important and distinct roles.

Asset Owners

Asset owners are the economic owners of assets that are invested in the real economy. Examples of asset owners are pension plans, insurance companies, official institutions, banks, foundations, endowments, family offices, and individual investors, each of which has different investment objectives and constraints. Asset owners (inclusive of both institutional and individual investors) can invest in company stock either by purchasing that stock directly or by hiring an asset manager to invest on their behalf. When an asset owner utilizes the investment management services of an asset manager, such investments can be structured as separate accounts or commingled investment vehicles (e.g., mutual funds).

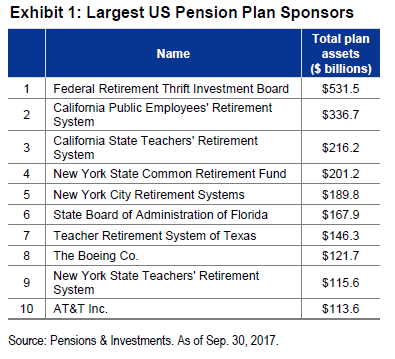

Asset owners own the investment risk associated with their investments, as well as any gains or losses in the value of those investments. Exhibit 1 provides a list of the largest US pension plan sponsors, which reflect some of the largest US-based asset owners. Even where an asset owner outsources management of all or a portion of its assets to an asset manager, asset owners make strategic decisions about their portfolios including asset allocation, portfolio objectives, constraints, and investment strategy. As discussed in this paper, asset owners can also establish sustainability (e.g., ESG) policies and decide how to vote in public companies. Asset owners may utilize the advice of investment consultants or other types of advisors in making these strategic decisions.

Asset Managers

Asset managers are professional investment firms that can be hired by asset owners to manage all or a portion of the asset owner’s portfolio. It is estimated that about three-quarters of the world’s financial assets are managed directly by asset owners, whereas about one-quarter are managed by asset managers. Asset managers are fiduciaries required to act in the best interest of their clients.

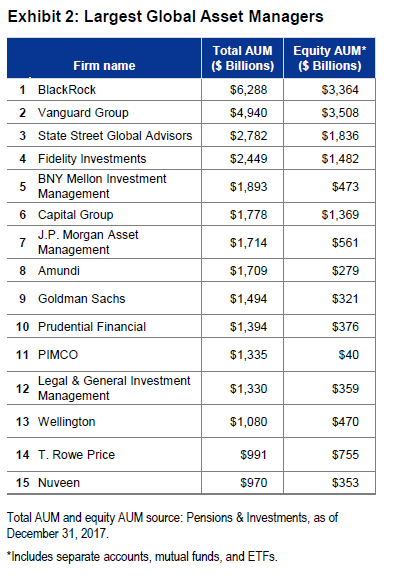

Importantly, even when an asset manager is managing assets on behalf of an asset owner, the asset owner continues to be the economic owner of the assets. Since asset managers are not the economic owners of the assets under their management (AUM), asset managers do not participate directly in the economic results of companies in which they invest. Instead, asset managers earn a fee based on the amount of AUM. These fees are typically structured as a small percentage of the total value of the client’s portfolio. Exhibit 2 lists the largest asset managers by AUM as of December 2017, and shows the amount of assets invested in equities.

Index Providers

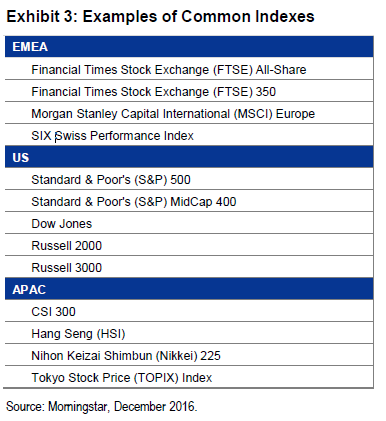

Index providers are responsible for creating and maintaining index methodologies that are designed to reflect the composition of a basket of securities that the index provider believes are representative of a given market. Equity indexes may focus on a capitalization range (e.g., large cap), a regional area (e.g., global, US, emerging markets), a sector (e.g., industrials, financials, consumer goods, etc.) and increasingly, factors (e.g., value, momentum). Indexes are often utilized as a performance reference for asset owner portfolios, commingled investment vehicles and separate accounts. Indexes are privately owned and licensed by the relevant index provider to users of indexes—typically asset owners, asset managers, or other financial intermediaries. Index providers define the index inclusion rules, which determine the securities that comprise each index. The largest equity index providers are MSCI, S&P Dow Jones, and FTSE Russell. Exhibit 3 highlights some of the most commonly referenced indexes.

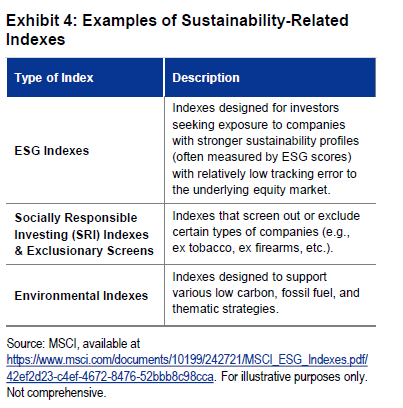

In choosing among market indexes, asset owners typically consider their investment objectives and requirements, as well as the innovation and incremental improvements in the construction of each index offered by index providers. The ability to choose one market index over another promotes a competitive and innovative marketplace. As such, index providers seek to create indexes that can compete for adoption. Increasingly, asset owners are seeking indexes that reflect ESG information as a component of the index construction methodology. In response to this demand, index providers have developed ESG-oriented indexes, including S&P Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes, FTSE4Good Indexes, and MSCI ESG indexes. Examples of various types of sustainability-related indexes are described in Exhibit 4.

Indexes are rebalanced on a regular basis. Each index has its own methodology for rebalancing that is determined by the index provider. For example, the FTSE Russell Indexes are rebalanced annually. The most recent FTSE Russell index rebalancing was completed at the end of June. The 018 FTSE Russell rebalance resulted in more than $39 billion in equities traded during Nasdaq’s closing auction on the day of the rebalance. The S&P Equity Indexes are rebalanced on a quarterly basis. MSCI reconstitutes semi-annually in May and November to recalibrate the index universe, and rebalances quarterly to reflect significant moves of securities within the index. The MSCI May semi-annual review led to approximately $23.9 billion in buys and sells for the developed markets indexes and $11.2 billion for the emerging markets indexes.

Index Inclusion and the Unequal Voting Rights Debate

Recently, several index providers have grappled with the treatment of companies with unequal voting rights structures in their indexes. Following are highlights of decisions made by S&P Dow Jones, FTSE Russell, and MSCI regarding inclusion of companies with unequal voting rights in their indexes.

In July 2017, S&P Dow Jones announced that it would exclude companies with multiple-share class structures from inclusion in the S&P Composite 1500 and component indices (including the S&P 500, S&P MidCap 400, and S&P SmallCap 600). Companies that had already been included in those indexes were grandfathered.

FTSE Russell also announced in July 2017 that it would begin excluding from all standard FTSE Russell Indexes, companies that have less than 5% voting stock held by unrestricted public shareholders. For existing index constituents, this change will become effective in September 2022, effectively permitting a temporary grandfathering of existing index components.

Likewise, in November 2017, MSCI announced its decision to temporarily treat any securities of companies with unequal voting structures as ineligible for certain of its indexes. Given feedback from clients, in January 2018 MSCI initiated a consultation that proposed adjusting company weightings based on the companies’ public voting rights without grandfathering existing companies. As part of the investment stewardship process, BlackRock and others submitted letters to MSCI expressing concerns or support for the proposed approach. BlackRock’s Open Letter Regarding Consultation on the Treatment of Unequal Voting Structures in the MSCI Equity Indexes is available on our website. MSCI recently announced their decision on inclusion rules has been delayed until October 2018.

In our view, policy makers, not index providers should set corporate governance standards. While we agree with the sentiments expressed by index providers that “one share for one vote” is the preferable structure for publicly-traded companies, we believe that this issue should be addressed by regulators. In our view, broad market indexes should be as expansive and diverse as the underlying industries and economies whose performance they seek to capture. In constructing indexes, index providers should make every effort to reflect the investable marketplace in the broad benchmark indexes that they produce. We believe that if index providers want to address the dual share class issue within their index methodologies, they should do so by utilizing methodologies that take into account voting rights as part of their ESG index series, since this is clearly a “G” issue.

Proxy Advisors

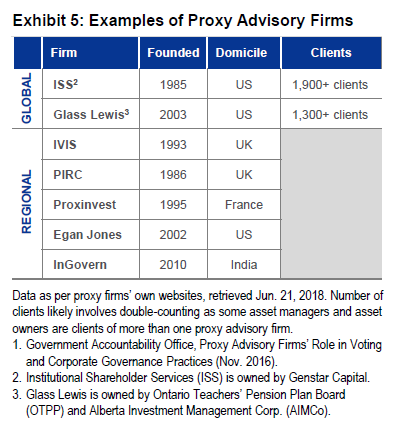

Proxy advisory firms are a critical component of the proxy voting system, providing research and recommendations on proxy votes. Proxy advisory firms also provide voting infrastructure and some provide consulting services to public companies. The first dedicated proxy advisory firms were founded in the 1980s. Today, there are two global firms and numerous regional firms, as shown in Exhibit 5. The dominant firm in terms of market share is Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS).

Both asset owners and asset managers use proxy advisory firms in different ways and rely on them to a different extent. Some investors (inclusive of asset owners and asset managers) have their own in-house proxy voting and stewardship functions that use the research from proxy advisory firms as an input into their investment stewardship process, whereas others rely more heavily or even exclusively on the recommendations of proxy advisors for deciding how to vote. Given the large number of votes that take place during proxy season each year, many investors rely heavily on the recommendations of proxy advisors to determine their votes, as they may not have the resources to individually analyze each proposal in detail. As a result, proxy advisors can have significant influence over the outcome of both management and shareholder proposals.

Recently, proxy advisory firms have attracted the attention of policy makers who want to understand how proxy advisors determine their voting recommendations and manage conflicts of interest. Some policy makers have called for legislation or regulation that would require greater transparency and enhancements to proxy advisors’ processes for determining voting recommendations.

What is Investment Stewardship?

Investment stewardship refers to engagement with public companies to promote corporate governance practices that are consistent with encouraging long-term value creation for shareholders in the company. Engagement and voting provide shareholders an opportunity to express their views.

When an asset owner invests directly in company stock, the asset owner makes its own decisions as to whether and how to vote their shares, as well as any other investment stewardship activities they choose to undertake. Asset owner proxy voting decisions can be based solely on the asset owner’s independent analysis, or can be based on the research and recommendations of a proxy advisory firm.

When an asset manager is involved, the responsibility for investment stewardship is often delegated to the asset manager by the asset owner. Many asset owners, though, choose not to delegate their investment stewardship activities to their asset manager(s). For example, at BlackRock, we have many equity separate account clients who do not delegate voting authority to BlackRock. In the case of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), each fund’s board of directors has oversight of the asset manager, including its voting policies. Like asset owners, asset managers may use proxy advisor research as part of their investment stewardship activities.

Proxy voting is often associated with investment stewardship, however, voting is not the only form that stewardship can take. Engagement can also be an important component of asset owners’ and asset managers’ stewardship activities. Engagement can include one-on-one meetings with representatives of company boards and/or management, writing letters to companies, and a variety of other activities. Different investors take different approaches ranging from simply following the voting recommendations of proxy advisors. The approach often depends on the investment strategy, objectives, time horizon, and the investor’s view as to material drivers of financial performance. For the most part, the focus of investment stewardship activities is governance-related (e.g., board composition, the board’s oversight role). In the sidebar discussion on page 11, we explain the differences between activist investors, active investors, and active engagement by index fund managers.

Regulations and stewardship codes often require asset managers to vote proxies on companies in which they invest on behalf of clients to the extent their clients have delegated voting authority to the asset manager. For example, in the US, both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Labor (DoL) have issued guidance stating that as fiduciaries, asset managers must vote proxies when doing so is in the best interests of their clients.

Further, the forthcoming EU Shareholder Rights Directive will require EU-based asset managers, pension funds and insurers to disclose “the voting rationale for their most significant votes.”

Many have asked how to measure the impact of investment stewardship. The simple answer is that investment stewardship is a deliberate undertaking that is designed to encourage long-term structural improvements, not short-term, quick results. It is unlikely, for example, that investment stewardship will result in quarterly changes in corporate behavior–and it would be a mistake to judge the impact along these lines. A good way to think about the impact of investment stewardship is to look at longer-term structural changes on key, material governance issues. Ten years ago, for example, it was not uncommon to find a sitting CEO in a director seat on multiple public companies. Likewise, it was considered reasonable for an independent director to serve on six or more boards. Today, these norms have shifted as active investment stewardship efforts on these issues have contributed to improvements in corporate governance at public companies.

BlackRock’s Approach to Investment Stewardship

BlackRock’s approach to investment stewardship is driven by our role as a fiduciary to our clients, the asset owners. In this role, we look to engage constructively with company management to maximize the value of our clients’ investments in each individual company. BlackRock has had an in-house team dedicated to investment stewardship since its inception. The team is organized regionally, reflecting the different regulatory requirements, corporate governance practices, and client expectations in different jurisdictions. BlackRock has over 30 professionals in this area, which represents the largest dedicated investment stewardship capability in the asset management industry to our knowledge, and we have announced plans to continue to invest in this function.

Transparency and Compliance

BlackRock is committed to transparency. In all regions we publish our engagement priorities, our voting guidelines, our voting record, and occasionally provide detailed vote bulletins. Every quarter, for each region, we report on our voting and stewardship engagements. We also publish our full voting record and summary voting and engagement statistics annually.

BlackRock complies with its fiduciary and regulatory responsibilities to its clients with respect to proxy voting, and complies with market-level stewardship codes where applicable. In addition, BlackRock has signed on to several statements on stewardship, which include committing to undertaking activities to monitor the corporate governance of portfolio companies. Similarly, BlackRock has been a signatory to the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) since 2008, and produces a report annually that is assessed by the PRI.

Engagement

Engagement is core to our stewardship program as it helps us assess a company’s approach to governance in the context of its specific circumstances. Engagement conversations in the US are generally held with management and sometimes with independent board members. Our Investment Stewardship team engages extensively with companies around the world on issues that we have identified as material to companies’ long-term

financial sustainability, and votes on behalf of our clients and funds that have delegated voting authority to BlackRock. We engage with companies for four main reasons:

- We are preparing to vote at the company’s shareholder meeting and need to clarify the information in company disclosures;

- There has been an event at the company that has impacted its performance or may impact long-term company value;

- The company is in a sector or market where there is a thematic governance issue material to shareholder value;

- Our corporate governance risk analysis has identified the company as lagging its peers on ESG matters that may materially impact economic value.

In 2017, our Stewardship team had nearly 1,500 direct company engagements globally. Exhibit 6 provides an overview of our engagement meetings in 2017, highlighting that the majority of engagement meetings are focused on governance issues. In addition, over the past several years, we have written letters to company CEOs emphasizing the importance of a long-term approach. In these letters, we have asked company management to articulate their long-term growth strategies, to ensure proper governance, and to address other material issues relevant to their business models.

Exhibit 6: Breakdown of Engagement Meeting

BlackRock’s Investment Stewardship team seeks to engage in a constructive manner with companies. Our aim is to build mutual understanding and to ask probing questions, not to tell companies what to do. Where we believe a company’s business or governance practices fall short, we explain our concerns and expectations, and then allow time for a considered response. As a long-term investor, we are willing to be patient with companies when our engagement affirms they are working to address our concerns. However, our patience is not infinite—when we do not see progress despite ongoing engagement, or companies are insufficiently responsive to our efforts to protect the long-term economic interests of our clients, we will exercise our right to vote against management recommendations.

Given the increased level of interest in our Stewardship team’s work, we decided to publish our 2018 Engagement Priorities. They are intended to provide more information to clients, companies and other relevant stakeholders on issues our team will focus on over the period and how we will engage with companies. Engagement on these themes, particularly where we believe a company could evolve its practices, may require several meetings, so we maintain our focus for at least two years. We also engage on a range of other governance and voting matters as they arise, including special situations, such as mergers or other control issues. The sidebar on the following page includes case studies around our recent engagements in the pharmaceutical and energy sectors.

Examples of BlackRock’s Investment Stewardship Engagements

Our engagement can be quite varied depending on the industry and region. Below we discuss two recent examples of engagement in the pharmaceutical and energy sectors. In all cases, we act in our fiduciary capacity to ensure that the long term value of our clients’ assets were adequately safeguarded.

Pharmaceutical Industry Engagement

In light of the risks presented to certain pharmaceutical companies stemming from the opioid epidemic in the US, we engaged with companies across the pharmaceutical sector about their enterprise risk management practices and anticipated public policy changes that might affect their long-term strategy.

For the most part, these engagements led to mutual understanding about how companies were addressing these risks to their businesses. For those companies that are in the business of manufacturing opioids, many had taken steps to enhance oversight of supply chain risks, had elevated the issue to a board-level risk committee, and had instituted more robust remedial measures.

However, one company engaged in the development, sale, and licensing of products for pain relief had not, in our view, demonstrated that the board and management took a sufficiently robust approach to opioid risks. Based on our engagement, we believed that it was unlikely that the company would improve its reporting such that investors could understand how the company would mitigate these material risks. Accordingly, we supported a shareholder proposal that called for a report on the governance measures the company had implemented \”to more effectively monitor and manage financial and reputational risks related to the opioid crisis in the United States, given [its] manufacturing and past sale of opioid medications.”

The proposal received approximately 62% support and our engagement is ongoing.

Energy Sector Engagement

We have similarly engaged companies across the energy sector, in the US and internationally. In the second quarter of 2017 we proactively engaged with 27 US companies on carbon-related risks; 21 of which had shareholder proposals seeking improved disclosure around climate change. Regardless of whether a shareholder proposal appears on the ballot, the aim of our climate risk engagements are twofold: 1) to gain a better understanding, through disclosures, of the processes that each company has in place to manage climate risks, and 2) to understand how those risks are likely to impact the business.

25 of the 27 companies we engaged with—including four major global producers and refiners—demonstrated a willingness to continue to improve their climate-related disclosures. This, in our view, presented the possibility for a more effective disclosure process than what had been sought in the shareholder proposals on those company ballots. As a result, in those instances, we voted against the shareholder proposals.

However, where we did not see meaningful progress despite past engagement, or where companies appeared insufficiently willing to respond to our concerns—which was the case for two global producers and refiners—we voted against management recommendations and supported shareholder proposals calling for greater disclosure. These proposals received 62% and 67% support, respectively, and our engagement continues.

Proxy Voting

In addition to engaging directly with companies, we vote at more than 17,000 shareholder meetings globally each year, on over 160,000 ballot items.

Our voting guidelines are the benchmark against which we assess a company’s approach to corporate governance and the items on the agenda for the shareholder meeting. Our guidelines are applied pragmatically, and differ region by region, often with variations at the national level. Our vote decision is taken to achieve the outcome that we believe best protects our clients’ long-term economic interests. The guidelines are reviewed annually and updated as necessary to reflect: (1) changes in market standards; (2) evolving governance practices; and (3) insights gained from engagement over the prior year.

As most companies are well-run with effective boards and competent management, our starting position is to support management unless severe governance or performance concerns are identified. We engage in instances where we believe issues are material to a company’s long-term performance, and give management time to address the issue. Often through our engagement, we gain a better understanding of management’s approach and why it is in the interests of long-term shareholders. Even when we continue to be concerned, we find continuing, constructive engagement is the best way to communicate our perspective.

While we are generally supportive of management, we believe board directors are elected to represent shareholder interests, among other things. As such, much of the focus of our proxy voting is on director accountability. Where we have concerns that the board is not dealing with a material risk appropriately, we may signal that concern by voting against the re-election of certain directors we deem most responsible for board process and risk oversight. We vote against management (including re-election of directors) if the company is consistently unresponsive or seems not to be acting in the long-term interests of shareholders. Often we vote against individual directors due to poor attendance records and/or over-boarding.

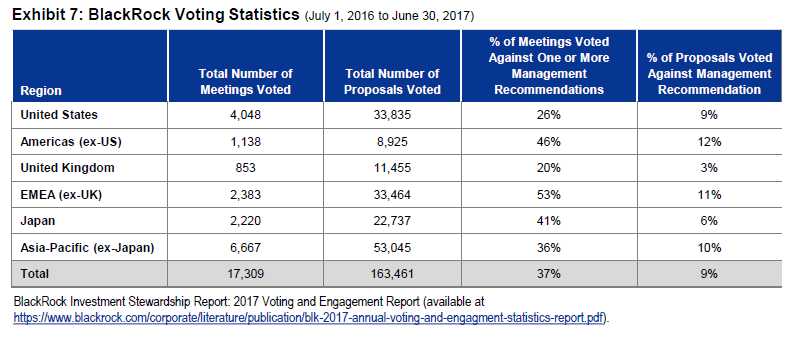

As shown in Exhibit 7, we sometimes vote with management and sometimes vote against management. There are also differences in our voting patterns depending on the region in which the company is based.

Shareholder Proposals

Shareholder proposals are one mechanism for shareholders to put an issue on the ballot at a company’s shareholder meeting. Although many market regulations accommodate some form of shareholder proposal, in the US shareholder proposals have become a feature of company annual meetings especially for large cap companies. Under US regulations, shareholders holding $2,000 worth of shares, or 1% of the shares entitled to vote, for at least one year, may file shareholder proposals.

A subset of asset owners, and some asset managers use shareholder proposals as a tool to signal investor concern to companies about emerging issues and/or as a catalyst for engagement. Larger companies tend to receive the majority of the proposals each year, although some are filed at smaller companies in certain sectors. Very few shareholder proposals pass. In 2017, about 14% received majority support from investors. Under SEC rules, proposals that do not pass but receive sufficient support can be resubmitted in subsequent years if certain resubmission thresholds are met. Although most shareholder proposals are non-binding, such that management do not have to act even on those proposals that pass, proxy advisory services and some investors may seek to penalize a company that fails to address proposals with increasing or majority shareholder support, often by voting against directors standing for election.

Under Securities and Exchange Act Rule 14a-8, companies can exclude from the ballot proposals that do not meet certain procedural requirements or can seek ‘no action relief’ from the SEC to exclude certain proposals. The most common reasons this relief is granted are if the proposal is in direct conflict with a management proposal or the company has already substantially implemented what the proposal seeks to address.

Companies can also discuss shareholder proposals with its proponents, and if an agreed upon outcome can be reached in advance of the vote, the shareholder could withdraw the proposal. Withdrawals of shareholder proposals occur with some frequency. For example, of the 608 shareholder proposals filed in the 2017 Form N-PX filing year, 123 (20.2%) were withdrawn.

With respect to BlackRock’s approach to shareholder proposals, our engagement on material ESG issues does not begin or end with a vote on a shareholder proposal. During our direct engagements with companies, we address the issues covered by any shareholder proposals that we believe to be material to the long-term financial returns of that company. Where management demonstrates a willingness to address the material issues raised, and we are satisfied with the progress being made, we will generally support the company and vote against the shareholder proposal. Sometimes, proposals we might have otherwise supported are withdrawn from company ballots due to engagement by the proponents and other shareholders that resulted in the company voluntarily adopting additional disclosures similar to what the shareholder proposal had called for.

We also vote against shareholder proposals that, in our assessment, are too prescriptive or narrowly focused, deal with issues we consider to be the purview of the board or management, or where the company is already reporting in the spirit of the shareholder proposal even if not in its exact format. Our interpretation of the gradual decline in the number of shareholder proposals and levels of support over the past few years is that direct engagement is building mutual understanding between companies and their long-term investors on emerging issues, particularly as it relates to “G” proposals. That said, in some instances BlackRock supports shareholder proposals on material E, S, and G issues when we do not see demonstrated commitment to address investor concerns or the company has made insufficient progress.

While BlackRock votes on shareholder proposals that are on company ballots, we have never filed a shareholder proposal on any company’s proxy statement or initiated a proxy fight. In addition, BlackRock has never sought a seat on a public company board as part of its stewardship activities.

Data-Driven Discussion of Voting Records

Voting records of registered US mutual funds are public. Every August all mutual funds are required to file a full voting record for each US registered mutual fund on Form N-PX with the SEC. As part of our commitment to transparency, BlackRock includes links to those filings on our investment stewardship website (https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/about-us/investment-stewardship). The discussion in this section is based on publicly available data for US companies in the Russell 3000 Index, followed by a brief discussion of shareholder proposals as well as BlackRock’s approach to voting.

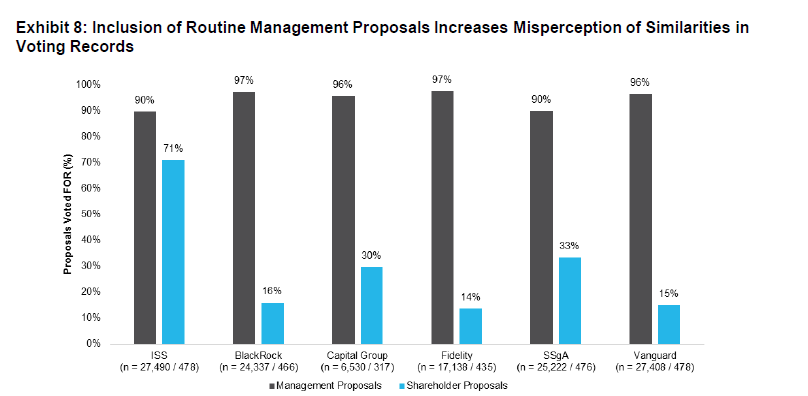

BlackRock votes on thousands of company-sponsored ballot items and shareholder proposals in the US each year. Management proposals often relate to routine matters such as the reappointment of auditors. Most asset owners and asset managers including BlackRock are usually supportive of management on such routine proposals. In analyzing voting data, the presence of tens of thousands of routine and non-controversial votes can increase correlations between the voting statistics of various shareholders, even if they take significantly different approaches to proxy voting, and investment stewardship more generally. To put this in perspective, in 2017, there were nearly 28,000 ballot items on proxies of Russell 3000 companies, of which more than 27,000 were management proposals. In certain instances, the inclusion of non-controversial ballot items in analyses of voting data has resulted in the misperception that the voting records of most large asset managers are highly correlated amongst asset managers and with the recommendations of proxy advisors. As demonstrated in Exhibit 8, this is not the case with respect to more controversial votes, like shareholder proposals.

Shareholder proposals tend to be more contentious than management proposals. These proposals receive greater public and media coverage, amplifying their non-routine nature. As a result, looking at data on shareholder proposals can provide greater insight into the variation in voting records and approaches to investment stewardship among different types of investors. As discussed in the previous section, when shareholder proposals are on the ballot, we evaluate each on its merits in the context of materiality to the company’s long-term financial performance.

As highlighted in Exhibit 8, based on a review of shareholder proposals that were voted on in the 2017 SEC Form N-PX filing year by asset managers who held shares in companies in the Russell 3000 Index, the voting patterns differ considerably across various asset managers and the managers’ records differ strongly when compared to ISS recommendations. Exhibit 8 is based on public filings by US registered mutual funds; this data is regularly analyzed by parties interested in voting such as academics, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the media, and corporate advisory firms.

Understanding Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Considerations

The term ESG has become a catchall phrase that often means different things to different people. This has created the need to better define what is meant by ESG and how ESG factors may be incorporated into portfolio management activities conducted by asset managers. ESG is often misunderstood to suggest that ESG is about inserting social or political values into investment activities. This is not the case. While some asset owners may choose to avoid certain assets that do not align with their social or political views or seek out ones that do, incorporating ESG factors into the investment process is about enhancing risk-adjusted financial performance. This is particularly true for asset managers who have a fiduciary responsibility to their clients, and therefore must work to maximize the long-term value of client investments., BlackRock’s number one goal is to maximize long-term value for our clients. Asset managers cannot utilize client assets to push their own social or political views, though they may offer socially responsible investment (SRI) strategies where clients specifically request these strategies. Considerations of material sustainability insights are incorporated into portfolio management in different ways, as discussed below.

The BlackRock Investment Institute recently issued a report entitled Sustainable Investing: A “Why Not” Moment, which explores the key ways that incorporating sustainable investing insights into portfolios can improve outcomes. In addition, the paper highlights deficiencies in existing ESG data, which requires going beyond headline figures such as ESG scores to understand the investment implications of a given ESG factor.

Integrating ESG Insights into Investment Processes

Business-relevant sustainability issues (including those related to ESG matters) can contribute to a company’s sustainable long-term financial performance. Companies that manage sustainability risks and opportunities well tend to have stronger cash flows, lower borrowing costs and higher valuations, as concluded in a study conducted by MSCI. Another study suggests US firms with strong track records on key sustainability metrics have significantly outperformed those with poor report cards. Thus, incorporating these considerations into the investment research, portfolio construction and stewardship process can enhance long-term risk-adjusted returns.

Differences between: Activist Investors, Active Managers, and Active Engagement

All asset managers, whether following absolute return, relative return, factor, or index strategies, have the ability to vote proxies based on the number of shares they hold across various portfolios where clients have delegated voting authority to the asset manager. One of the concerns raised by commentators over the past decade has been that “index managers” should not be passive with regards to engagement with the companies whose stocks the index funds hold.

Over the past decade, there has been increasing pressure from some commentators and policy makers for asset managers and asset owners to engage with companies on a variety of topics, including long-term performance and ESG issues. Some have gone as far as to state that “the current level of the monitoring of investee companies and engagement by institutional investors and asset managers is often inadequate and too focused on short-term returns, which may lead to suboptimal corporate governance and performance of listed companies.”

Activist investors

Activist investors are primarily private fund managers whose strategy is to take a large position in a company and then vigorously advocate for significant corporate changes. The activist might seek board seats or encourage management to consider a merger or break up a company into multiple entities. While they are often criticized for advocating for corporate strategies that maximize short-term profits rather than taking a longer-term view, activists argue that they unlock value for shareholders.

One of the concerns that has been raised is that index funds prevent activists from improving companies. In the case of BlackRock, we sometimes support activists and sometimes support management. In the 2017 N-PX filing year, BlackRock supported 5 of 27 proxy contests, or approximately 19% of proxy contests.

Some investors actively use the shareholder proposal process to promote issues that are considered by some to be social or political issues. These investors tend to be the faith-based, public, and labor funds that are actively engaged investors who may be focused on outcomes beyond governance or sustainable long-term performance. Although referred to as “activists”, these investors are different from the activists focused on financial and strategic corporate change.

Active managers

Active managers can pursue a variety of different investment strategies that seek to achieve returns above and beyond those returns provided by a representative market index. Some active strategies are designed to beat the performance of a benchmark within the confines of various risk parameters, while other strategies focus on absolute return. In the course of managing active portfolios, portfolio managers may view engagement and proxy voting as a means of encouraging a particular outcome at a company that is aligned with their investment views. At BlackRock, this sometimes results in active portfolio managers voting differently than other BlackRock portfolios (i.e., index funds).

While there are a variety of active investment styles, active managers do not generally seek seats on the boards of portfolios companies. UCITS for example, effectively prohibit managers from taking a board seat or controlling vote.

In voting their proxies, some managers perform their own analysis and may engage directly with the companies in their portfolios; others rely extensively on proxy advisory services. Importantly, if an active manager is unhappy with the management of a given company, he/she can reduce his/her position or sell the company’s shares entirely.

Engagement by Index Managers

In contrast, an index fund will hold a stock for as long as it remains in the benchmark. Index fund managers engage with companies and vote their proxies in order to express their views, focusing on the long-term value of the company. In the paper, “Engagement: The Missing Middle Approach in the Bebchuk-Strine Debate,” Matthew Mallow and Jasmin Sethi explain that one can have active engagement with a company without being an activist. The paper “Passive Investors, Not Passive Owners” finds that index investors improve corporate governance practices at companies. Index managers generally limit engagement to corporate governance topics such as the qualifications of directors, the time they have to devote to their duties, executive pay, or material ESG issues.

Voting data is more nuanced than threshold reporting data

Another set of data that is often referenced when considering the voting power of an asset owner or asset manager are regulatory threshold disclosures filed by asset owners and asset managers (including, for institutional investors, Form 13F filings in the US). However, voting data is more nuanced than threshold reporting data. As discussed below, these nuances can have material implications for the interpretation of threshold data.

First, for asset owners investing directly in company stock, threshold reporting data is helpful in understanding their economic ownership of the stock. The same is not the case for asset managers because threshold data reflects assets under management in the case of asset managers, rather than economic ownership of the shares. Asset managers are required by regulations in various jurisdictions to submit threshold disclosures for all AUM over which the manager exercises investment and/or voting discretion. This means that the threshold reporting numbers of asset managers generally reflect aggregate holdings of the stock of an individual company that may be held in multiple portfolios, including a broad range of mutual funds and separate accounts of diverse asset owner clients. In practice, dozens or even hundreds of portfolios—using different investment strategies—at a single asset manager may each own stock in the same company.

Second, threshold reporting data is often misinterpreted as a proxy for asset manager voting power in a given company. For example, in BlackRock’s case, threshold reporting overestimates the amount of shares over which BlackRock has voting authority. Simply put, threshold reporting aggregates equity holdings across all equity portfolios managed by BlackRock, even though BlackRock does not have voting authority for all client accounts. Specifically, some of our equity separate account clients choose not to delegate voting authority to BlackRock. We estimate that approximately one-quarter of equity separate account assets managed by BlackRock do not delegate voting authority to BlackRock. This represents approximately 9% of assets in equity mandates managed by BlackRock. In addition, there are certain companies for which BlackRock is required to outsource voting to an independent fiduciary due to perceived or potential conflicts of interest as well as to comply with certain regulatory requirements. We estimate that across equity holdings managed by BlackRock, approximately 8% of AUM is outsourced to an independent fiduciary to vote.

In addition, not all BlackRock portfolios vote the same way. BlackRock retains voting authority for substantially all commingled funds, however, active portfolio managers reserve the right to vote their shares differently than BlackRock’s index portfolios and sometimes they exercise this right. As of March 31, 2018, approximately 9% of the equity assets managed by BlackRock are managed in active investment strategies.

Our activities to integrate sustainability considerations into the investment process mirror the diversity of clients we serve, as well as the range of investment strategies and asset classes we offer. Across BlackRock, we provide all of our investment teams with data and insights to keep them well-informed of sustainability considerations. Equipped with the necessary data and tools, our active portfolio managers are able to bring decision-useful ESG information into their investment processes, discounting or emphasizing this information as they would any other financial input.

ESG and Investment Stewardship

Our clients are long-term investors, as demonstrated by the fact that about two-thirds of the assets BlackRock manages are dedicated to retirement purposes. It is over the longer term that ESG risks and opportunities tend to be material and have the potential to impact financial returns. Just as we expect the companies in which we invest to understand the macroeconomic and industry trends in which they operate, we believe that a company’s awareness of regulatory and societal trends helps drive long-term performance and mitigates risk. The best companies ensure that their investors, as well as other stakeholders in the company, have enough information to understand the drivers of, and risks to, long-term financial performance.

Unlike our actively managed investment strategies, our index portfolio managers do not have the discretion to add or remove a company’s securities from the portfolio as long as that company remains in the relevant index. As such, for index investing, investment stewardship activities are the mechanism available to asset managers to integrate and advance material sustainability-related insights. That said, asset owners can choose to invest in specialized indexes (as shown in Exhibit 5) that embed ESG factors into the index construction rules. At BlackRock, index investment mandates represent approximately 90% of our equity AUM. BlackRock’s investment stewardship efforts benefit from firm-wide data and insights on sustainability-related issues.

At BlackRock, we focus on those ESG issues that we believe have a material impact on long-term financial performance for companies in which our clients are shareholders. While the body of research and historical evidence is most robust for a set of “G” issues, there is growing evidence that “E” and “S” issues can affect long-term financial performance.

Sustainable Investment Solutions

Some asset owners choose to pursue investment strategies that incorporate sustainability insights as a central theme to mitigate risk and enhance long-term returns. Some of these products can also be used by clients to align their financial investments with their values by removing exposure to specific investments, or by generating positive social outcomes alongside market rates of return. We seek to deliver sustainable investment solutions that address a range of client motivations, empowering our clients to achieve their financial objectives.

BlackRock offers clients sustainable investment solutions that range from investments in green bonds and renewable infrastructure, to thematic strategies that allow clients to align their capital with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, BlackRock is the largest provider of sustainability-themed ETFs, including the industry’s largest low-carbon ETF, and we manage one of the largest renewable power funds globally. With deep expertise in alpha-seeking and index strategies, across public equity and debt, private renewable power, commodities and real asset strategies, we are continuing to build scalable products and customized solutions for clients across asset classes.

Conclusion

At BlackRock, we have a responsibility to generate the sustainable, long-term returns that our clients need to meet their financial goals. We believe in the value of direct engagement with the companies that we invest in on behalf of our clients, and we are continuing to invest to build our capabilities in this area. We are also leveraging new technology and tools within BlackRock in an effort to continually improve our investment stewardship efforts. Simultaneously, we are expanding our Sustainable Investing efforts, including the creation of a firm-wide research team focused on analyzing sustainability-related data to develop the clearest possible picture of how material ESG issues affect risk and long-term return. Finally, we are committed to offering clients a wide range of products that reflect their financial needs and their investment preferences.

A number of factors have combined to create increased interest in investment stewardship as well as in ESG issues. As discussed in this paper, it is important to understand the roles and responsibilities of various participants in the investment stewardship ecosystem. This includes asset owners, asset managers, index providers and proxy advisors. Often the preferences of asset owners drive critical decisions around asset allocation decisions, ESG policies, and voting policies. From an asset manager perspective, it is important to consider material ESG issues as part of the investment process, including investment stewardship. In addition, asset managers need to offer products that appeal to clients. Increasingly, clients are asking for ESG-oriented products, and often these are associated with ESG-oriented indexes.

Investment stewardship encompasses both engagement with companies and the voting of proxies. In a given year, there are thousands of ballot items that need to be considered and voted upon. The vast majority of these are routine management proposals that garner high levels of support. A review of voting data on proposals—both management and shareholder—for companies represented in the Russell 3000 Index shows that the inclusion of routine management proposals increases similarities in voting records across the industry. However, when we look at more controversial proposals like shareholder proposals, the voting patterns differ considerably across the largest asset managers and the managers’ records differ strongly when compared to ISS recommendations. BlackRock takes an engagement-first approach, emphasizing direct dialogues with companies on issues that have a material impact on financial performance. In voting, we carefully consider each ballot item.

Investment stewardship and sustainable investing are both areas that are evolving industrywide. BlackRock is committed to investing in these areas as we look to generate long-term sustainable performance for our clients.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print