Ed Batts is partner and Sara Gates is an associate at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP. This post is based on an Orrick memorandum by Mr. Batts and Ms. Gates.

Corporate governance features have become increasingly prominent for public companies. This has accelerated as economic-oriented activist investors team with institutional investors to serve as catalysts for change.

We are often asked by clients in the course of our practice:

What do other companies do?

We thought it would be useful to compare the three primary governance documents—the certificate/articles of incorporation, bylaws and corporate governance guidelines—of publicly traded companies in the energy sector.

We focused on three general areas:

- Board of Directors

- Stockholder Actions

- General Provisions

Executive Summary

Proxy access

Has grown fast, as just over 60 percent of surveyed companies have adopted provisions which in general allow groups of up to 20 stockholders, who combined have held at least 3 percent of a company’s common stock for at least 3 years, to nominate candidates for up to 20 percent of the board of directors.

Exclusive forum provisions

Limit stockholder derivative class actions suits to a single legal jurisdiction—usually the state of incorporation, such as Delaware. Their adoption continues to surge. Almost one half of surveyed companies have adopted these provisions, which originated only a few years ago.

Director age limits

Almost two thirds of surveyed companies have adopted some age limit, but director tenure limits are non-existent notwithstanding increased proxy advisory scrutiny in this area.

Staggered boards

Remain surprisingly popular. Around 30 percent of energy companies have a staggered board. Unlike in other sectors where this tends to be

a feature of newer public companies, with the surveyed companies there does not appear to be an immediately discernible pattern as the companies with staggered boards vary by both market capitalization and age of the company.

Majority voting formulations

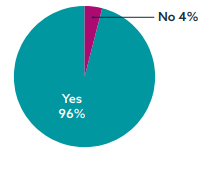

Continue to sweep. 90 percent of energy public companies have some variation of provisions requiring a director nominee to secure a majority of votes cast in an uncontested election. Almost all of these companies, however, allow the board to use their judgment to retain a director.

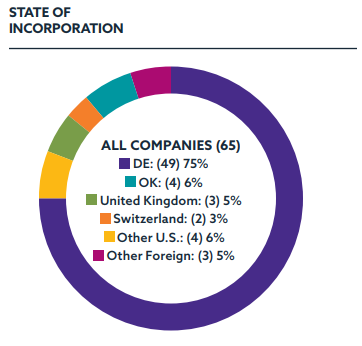

State of incorporation

Most but not all companies remain incorporated in Delaware. 49 of 65 companies are incorporated in Delaware, 8 in other states and 8 overseas.

Our Data Criteria

Our study encompassed the following:

- We looked at the 65 component companies combined from both the Dow Jones Energy Sector Index and the S&P 500 Energy Index, popular indices used for exchange traded funds for the energy sector. A full list of the surveyed companies is at the end of this post.

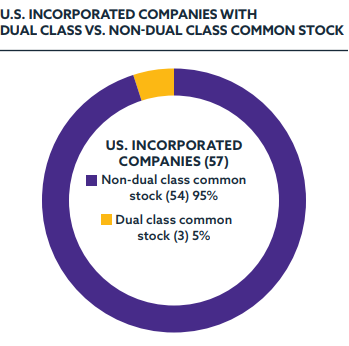

- 8 of the 65 surveyed companies have a long history and large presence in the U.S. but are actually organized overseas and we thus excluded them from our analysis given the lack of comparability.

- We then excluded any company with a dual class common stock structure. 3 companies had such structures, which customarily allocate 10 votes per share to a holder of a nonpublicly traded class of shares while the publicly traded shares receive one vote. These companies have very different governance profiles and a very different level of susceptibility to investor pressure than those that do not.

- This left a sample size of 54 U.S. incorporated, non-dual class common stock companies.

- Charters and bylaws must be filed on the SEC’s website, EDGAR, although in a limited number of cases, the filings predated the advent of EDGAR. Corporate governance policies are generally available on a company’s website. Where we noted inconsistencies between documents, we did not contact companies to resolve discrepancies.

Somewhat unique to the energy and pharmaceutical industries and largely in light of relatively recent tax-driven inversions since 2000, a non-trivial portion of companies—13 percent—are organized under laws outside the U.S., notably Switzerland, the U.K. and island nations such as Bermuda and Curacao.

Does the company have a classified/staggered board?

About 70 percent of surveyed non-dual class companies have boards elected in full every year. Unlike in other sectors where staggered boards are more likely with newer public companies, there was no immediately discernible pattern with surveyed companies. Those with staggered boards varied by market capitalization and age of company.

While proxy advisory firms have increased pressure on companies to eliminate classified boards, the concept remains very much alive in the energy sector.

PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: Both ISS and Glass Lewis do not support retention of classified boards.

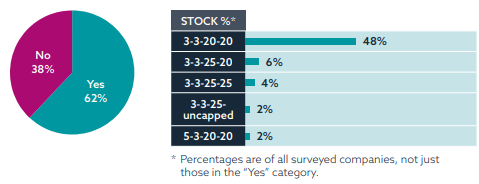

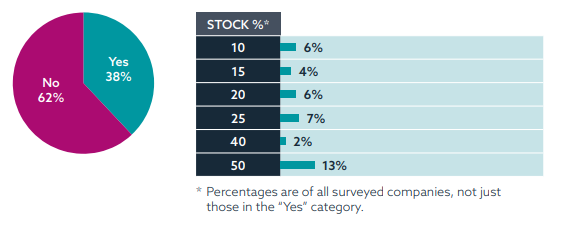

Do bylaws contain proxy access for election of board members?

In their most common form, proxy access provisions allow groups of up to 20, 50 or an unlimited number of stockholders who have collectively held at least 3 percent of a company’s shares for at least 3 years to nominate up to 20 percent of a company’s board nominees to be included nominees at 25 percent of the board, the vast majority of adopting companies in our survey chose the 20 percent cap, which is the emerging de facto standard.

Several large mega-cap companies on the national stage initially adopted such proxy access provisions, either proactively or in the face of stockholder pressure, particularly from institutional governance activists’ funds, such as the prominent efforts by New York pension plans.

The adoption rate is growing—and rapidly so. Almost two thirds of surveyed companies have enacted proxy access, again the vast majority using the 3 years/3 percent/up to 20 percent of Board/up to 20 stockholders together formulation. One expects this number to rise significantly, both as other companies use initial adopters for comfort and with the continued focus on this area by governance activists.

PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: ISS supports provisions allowing stockholders holding at least 3 percent for at least 3 years to nominate up to 25 percent of the board. Glass Lewis supports the concept generally but is non-committal regarding particulars.

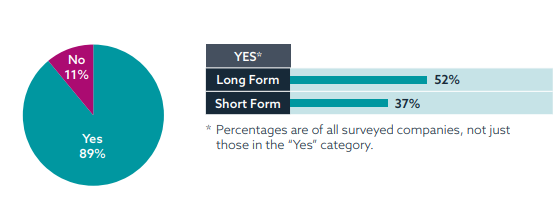

Do advance notice bylaws provisions require disclosure of derivative positions for nomination of director candidates?

These provisions explicitly require those who nominate director candidates (such as activists) to disclose any financial interest they have in the subject company that may not be in the form of actual stock ownership, such as derivative contracts that create synthetic economic ownership.

Only 10 percent of surveyed companies have not adopted these disclosure-only provisions. Of those that have, the majority have conversely adopted very detailed requirements on what constitutes a derivative position (e.g. synthetic equity). The others have adopted provisions that briefly describe items that must be listed. Certainly there seems to be little downside to requiring short or even better, long form disclosure, and one wonders about the substantive reasons behind the lack of adoption by the 10 percent that have not done so.

PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: ISS and Glass Lewis have remained silent on this feature.

Is there intent to serve language? If yes, does it apply only to stockholder nominees?

The annual crunch time for an activist investor to exert maximum leverage against a company is the deadline date for nominating director candidates or introducing a stockholder proposal at an annual meeting, whether for inclusion in the company’s proxy statement or alternately as a floor proposal. To put forward director nominees, an activist needs lead time to both secure candidates and vet them appropriately. In 2016, Corvex Management, led by Keith Meister, an Icahn protégé, nominated a full contest slate of 10 director candidates at The Williams Companies. All the candidates were Corvex insiders—but Corvex explicitly stated that the candidates were to be substituted out for substantive candidates after the deadline date. Before that concept could be fully tested, Williams named an additional two new outside board nominees and Corvex withdrew its slate.

In response to this clever attempted maneuver, some companies are amending their bylaws to require that a candidate evidence an ‘intent to serve’ a full term as director, in order to force nominees to be bona fide candidates at the time of the nomination deadline. This requirement is now found in 15 percent of the surveyed companies.

PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: Both ISS and Glass Lewis have remained silent on this feature.

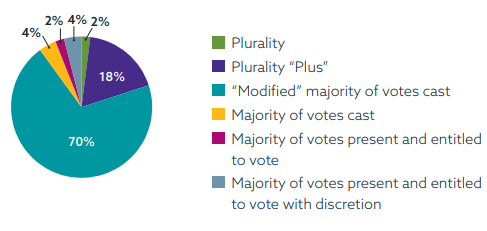

What is the voting standard in board elections?

Uncontested Director Election Standards: A Jumbled Landscape

Until about a decade ago, director voting in uncontested elections was relatively uncomplicated with the then-almost universal plurality voting standard in effect for both contested and uncontested director elections:

- Plurality: The candidate with the highest number of ‘for’ votes wins election. It is a relative standard—not an absolute numerical threshold. There is thus no need of an ‘against’ vote (and it should not appear on a proxy card!). Instead, the ‘withhold’ vote is the only way to voice displeasure at a particular candidate. In uncontested elections where a single candidate stands for election (and most often, re-election) the ‘highest’ relative standard means an incumbent director standing for uncontested re-election need only secure one (yes, a mere single) vote for re-election. This is the case even if the candidate receives millions of ‘withhold’ votes.

Governance activists at large institutional investors—particularly organized labor-oriented investment funds and public pension funds—objected that a plurality standard in uncontested elections means re-election of incumbent directors is a foregone conclusion no matter how much stockholders may object by submitting ‘withhold’ votes. These governance activists thus pushed for the introduction of so-called “majority voting.” While adoption of majority voting spread virally in the US public company population, it did so in a couple of mutations—and frequently with a confusing overlay of disclosure.

The key in these formulations is the interplay between three documents for a given company, listed in descending order of enforceability: (a) bylaws, (b) board corporate governance guidelines and (c) disclosure in the proxy statement for an annual meeting of stockholders that presumably summarizes resolutions adopted by a board. The corporate governance guidelines are adopted by a board—and may be waived by a board—and contain things such as the board’s policy on re-nominating board directors who exceed age or tenure limits. A company’s proxy statement for an annual meeting of stockholders is not a truly legally binding document.

Two “majority voting” paradigms ensued:

- Plurality ‘Plus’: The initial wave of ‘majority voting’ was actually a plurality bylaws standard superimposed with additional requirements outside of the bylaws, in the corporate governance guidelines—and occasionally just simply referenced in the proxy statement with no further explanation. The bylaws in these cases continue to state that a director is elected as long as he or she obtains the highest amount of “for” votes—no different from a conventional plurality standard. However, the corporate governance guidelines and/or annual meeting proxy statement state that all sitting directors shall in advance submit irrevocable resignations that are triggered if a director does not receive more “for” votes than “withhold” votes. Once the resignation is triggered, the remaining board then decides whether to accept or reject the pre-wired resignation. Governance activists are not generally proponents of this structure because the operative ‘majority voting’ provisions are usually in the governance guidelines—which is purely a board device and even more so than the board’s customarily delegated authority with bylaws—or worse yet, simply documented in meeting minutes as a board policy and then summarized in an annual meeting proxy statement.

- ‘Modified’ Majority of Votes Cast: A further evolution of ‘majority voting’ is to put the auto-resignation mechanism in the bylaws. The auto-resignation is an important feature to governance activists because it preempts the Delaware ‘holdover rule’. In a much-vaunted ‘failed election’ under majority voting, insurgent directors who do not obtain the requisite majority are not elected. But, in a twist of irony, under the Delaware holdover rule, incumbent directors who fail to obtain the requisite majority vote continue in their duties indefinitely. The holdover rule on a stand alone basis rule summarily defeats the purpose of the majority voting provision and risks the ire of governance activists, who thus insist on an auto-resignation mechanism.

The vote standard in a ‘modified’ majority system is expressed in the bylaws as a candidate is elected if the “for” votes exceed “against” votes. This is the favored route of governance activists—and where most companies have gone: 70 percent of surveyed companies have this standard. Given the bylaws codification, it makes sense to switch the term “withhold” votes to truly “against” votes—so that directors receive “for” and “against” votes.

There are three further potential vote formulations, each of which is stricter than ‘majority voting’ and its director resignation mechanism with the board—but extremely few companies have adopted any of them:

- Majority of Votes Cast: The bylaws require a majority of votes cast—under Delaware law, abstentions and broker non-votes thus are not in either the numerator or denominator—with no resignation policy set forth. Very few companies—only 4 percent of companies in our survey—have adopted this standard, since the absence of a resignation policy creates the possibility of a ‘failed election.’ Again, under Delaware law, if a company has a majority of votes cast standard without an auto-resignation policy, the effect is to make it more difficult for an insurgent director to be nominated, while having little practical impact on incumbent director nominees, who in a failed election will continue to serve on the board.

- Majority of Votes Present and Entitled to Vote: In this formulation, abstentions are counted as “against” votes and broker non-votes are not counted at all. It is a rigorous standard, and only 1 company in our survey has adopted it.

The most strict hypothetical formulation is below—but no company in our survey has adopted it:

- Majority of Shares Outstanding: Both abstentions and broker non-votes are counted as “against” votes. Given the exclusion of broker non-votes, it in practice is an unrealistic standard, and therefore is unsurprising that no company in our survey has been this aggressive.

The Practical Effects of Auto-Resignations and “Failed” Elections

Interestingly, in the relatively few elections where incumbents have failed to secure more “for” votes than “withhold/against” votes, boards in reviewing whether to accept or reject the auto-resignation have almost always found reasons to retain the defeated incumbent as a director given his or her purported unique skills and/or experience to serve on a given board. Consequently, as currently implemented and executed today, ‘majority voting’ is arguably less-than-substantive from the perspective of governance activists and a potential point of increased friction in the future.

Contested Director Election Standards: The Necessity of Plurality Voting

Note that for contested elections it is critical to have a plurality voting standard remain because often in proxy contests, no nominee will reach a majority of votes cast. If no nominee reaches that majority and the vote standard is a majority of votes cast, then a failed election would occur where the incumbent director of a Delaware corporation would continue to serve under the ‘holdover rule.’ Even if the incumbent director were to resign out of embarrassment, the insurgent would still not be elected and the remaining board would have discretion to appoint a replacement—either the insurgent or someone entirely different and potentially more sympathetic to the incumbent board. This all can happen even though the insurgent may secure more votes than the incumbent, but not enough to reach a majority of votes cast.

The Confused State of Vote Standards and Proxy Statements

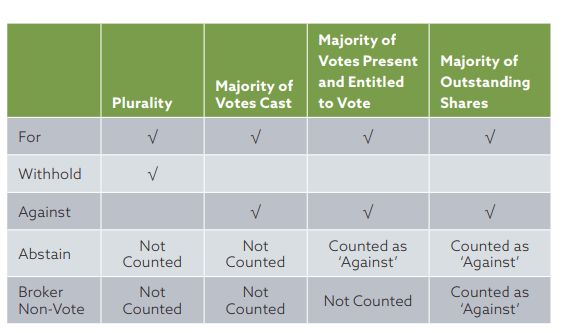

We reviewed proxy statements that appeared to inaccurately state either the voting standards and/or associated vote count procedures for things such as abstentions and broker non-votes—a not uncommon defect that has been noted with concern by the SEC. Combine 5 director vote standard formulations (plurality, plurality plus, modified majority, majority of votes cast and majority of votes present and entitled to vote) and add another 5 types of votes (“for”, “withhold”—for plurality—and “against” for all others, abstentions and broker non-votes) and one has a challenging disclosure obligation to summarize.

For clarity on one item that seems to create confusion in particular: Abstentions under Delaware law are not “votes cast” but are “votes present and entitled to vote”—accordingly, they count the same as “against” votes in majority of votes present and entitled to vote elections. Conversely, broker non-votes in Delaware are not considered eligible for voting—and so count neither as a vote cast or as a vote present and entitled to vote. However, broker non-votes are counted towards a quorum so long as a “routine” matter (e.g. approval of independent public accounting firm) appears on the ballot.

We summarize these Delaware vote standards below:

The rules are slightly different for NYSE listed companies, where (notwithstanding state law) broker non-votes cannot count as present for quorum purposes. To add to complexity, but separate from director elections, for NYSE listed companies that seek stockholder approval of certain matters, such as approval of equity plan changes, stock issuances or a change of control, abstentions are treated as votes cast and therefore in practice have the same effect as a vote against the proposal.

Almost 90 percent of companies have policies in place triggering resignations of incumbent directors who fail to receive more “for” votes than “withhold” (plurality plus) or “against” (modified majority) votes. This shows the dramatic expansion of majority voting formulations in the past decade.

PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: Both ISS and Glass Lewis support the ‘modified majority’ variant for director elections.

Is removal of directors restricted to “for cause” only?

Around one quarter of companies restrict the ability of stockholders to remove directors to “for cause” only—meaning that these companies do not allow for directors to be removed merely for performance issues, even if a supermajority of stockholders initiate a removal effort. Since the Delaware statutory default is that directors may be removed with or without cause, silence in the bylaws is the same as explicitly stating that directors can be removed with or without cause. Accordingly, when the ‘silent’ and ‘no’ buckets are combined, a total of three quarters of the surveyed companies allow director removal with or without cause.

Does the board have first and exclusive right to fill board vacancies?

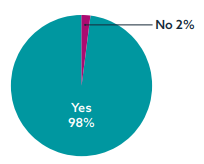

Almost all surveyed companies give the board the sole right to fill board vacancies.

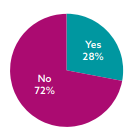

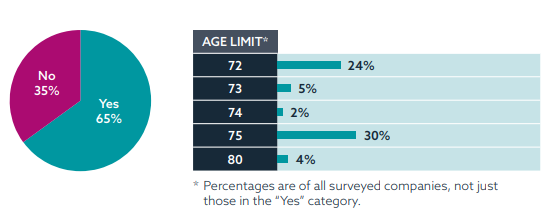

Has the company adopted director age limits?

So the saying goes, “72 is the new 70. And 75 is the new 72.” Two-thirds of surveyed companies have enacted formal age at 72 and nearly a third of surveyed companies at 75.

Has the company adopted director tenure limits?

Very few companies in the U.S. have specified board tenure limits, and all of the companies in our survey have yet to do so. This is another area of increased attention from governance activists and thus may evolve over the medium term.

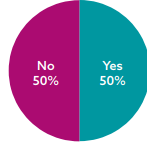

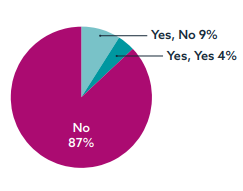

The separation of the Chair and CEO roles has been a hot topic in recent years—particularly as separation pressure gained significant momentum with high profile stockholder proposals to do so in the financial services industry. In response, many boards with combined roles have created lead independent director roles that in many respects mirror functions of a chair, without necessarily agenda setting, or of course, title. However, whether a company has an independent chair remains subject to wide variation, oftentimes dependent on the CEO’s history and personal inclination, as well as the company’s general performance. In fact, surveyed companies were evenly split in this regard. [box]PROXY ADVISORY POLICIES: ISS recommends generally a vote for stockholder proposals to separate the two positions, but their position is subject to individual evaluation with a focus on a fully functioning lead independent director position as well as financial and governance performance of the company. Glass Lewis also supports separation proposals but does so with a more stern avoidance of exceptions to this policy.Is there a combined CEO/Chairman role?

Can stockholders call special meetings and, if so, what percentage of outstanding shares is required to do so?

Roughly two-thirds of companies do not allow stockholders to call a special meeting. Of those that do, the percentage of shares required to call a meeting varies widely

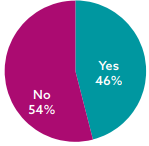

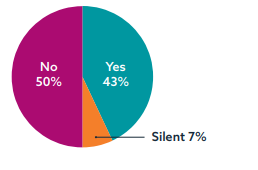

Can stockholders take action by written consent?

One half of surveyed companies do not allow action by written consent.

One half of surveyed companies do not allow action by written consent.

Mature companies without other ostensible blocking mechanisms for activists generally prohibit action by written consent in order to restrict fundamental corporate changes to actual meetings of stockholders. For those that do, voting requirements almost always mirror what would otherwise be required for a similar action at a meeting of stockholders.

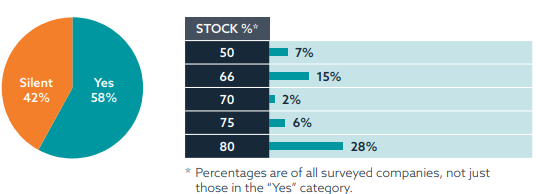

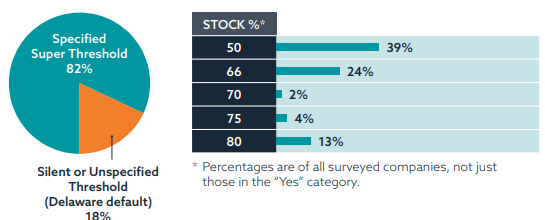

What percentage of vote of stockholders is required to amend bylaws?

Delaware law specifically vests stockholders the power to amend bylaws. But Delaware law also allows stockholders to permit boards of directors to so as well—and in practice almost all companies afford boards this discretion.

Delaware law specifically vests stockholders the power to amend bylaws. But Delaware law also allows stockholders to permit boards of directors to so as well—and in practice almost all companies afford boards this discretion.

Where companies allow the board to amend bylaws, stockholders may still amend the bylaws upon a proper vote threshold. In Delaware, that default standard is majority of votes cast, and thus abstentions and broker non-votes are not factored since neither “cast” a ballot. However, the Delaware default position is the minority for companies generally. Thus, only approximately 20 percent of surveyed companies have the default.

13 percent of surveyed companies retain the “majority” (50 percent) numerical threshold but change the vote standard to majority of votes present and entitled to vote. This means abstentions count as “against” votes but broker non-votes are not factored.

A full two thirds of surveyed companies change the denominator/vote standard to shares outstanding. This means broker non-votes count as “against” votes, in addition to abstentions. In practice, it is a difficult standard to meet, and made even more so for the over 40 percent of surveyed companies that hike the required numerical vote threshold above 50 percent—most to 66 percent. 10 percent of companies have 80 percent which effectively makes stockholder over-riding of a board highly unlikely.

In some cases, the greater vote requirement/standard is limited to matters concerning board size and removal (the matters most useful in a proxy fight), while for the rest of companies, the majority of outstanding—or super-majority of outstanding as it may be—requirement applies to the bylaws in their entirety.

What percentage of vote of stockholders is required to amend the certificate of incorporation?

For Delaware companies, Section 242 prevents stockholders from unilaterally amending the certificate of incorporation without initiation from the board of directors. Once the board recommends amending the certificate of incorporation, the Delaware default is that a majority of shares voting at a meeting can approve such an amendment and so abstentions and broker non-votes are not counted as having voted.

Approximately 40 percent of the surveyed companies follow the Delaware default by simply remaining silent on the subject. Conversely, nearly 60 percent of surveyed companies have enhanced standards that require a percentage of the outstanding shares to vote in favor of the amendment—in these formulations, abstentions and broker non-votes thus count the same as “no” votes. 28 percent of companies require 80 percent of outstanding shares and another 15 percent require at least 66 percent of outstanding shares. 7 percent of surveyed companies keep the Delaware numerical default of 50 percent but change the vote standard from Delaware’s majority of votes cast to the more stringent majority of shares outstanding.

In practice, a substantial portion of votes from brokerage account holders in “street name”, whether on behalf of institutions or retail investors, still take the form of broker non-votes, which again count the same as “no” votes in formulations requiring the vote of outstanding shares. For bylaws, a board can, so long as it has been delegated such authority (which most boards have), unilaterally amend the bylaws. However, a board cannot unilaterally amend the certificate of incorporation. Obtaining the affirmative vote of at least 80 percent of the outstanding shares to amend the certificate of incorporation—even when a board has recommended the amendment—this means that certificates of incorporation for such supermajority voting-standard companies are at significant risk not to change, even if the board has recommended doing so. This is sometimes referred to as the “zombie” effect.

Is “blank check” preferred stock authorized?

Unsurprisingly, almost all companies continue to allow boards to issue preferred stock at their discretion, or “blank check preferred.” While some governance activists decry this ability, it is particularly crucial for the adoption of stockholder rights plans (aka “poison pills”) and also in certain issuances to “white knights”—third parties who seek to disrupt a hostile tender offer.

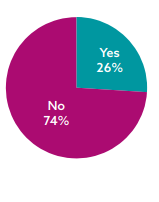

Is there an exclusive forum/venue provision?

Almost one half of companies have adopted exclusive forum bylaws, which restrict stockholder litigation to a single litigation forum/venue—almost always Delaware, as the favorite state of incorporation. Importantly, companies can elect to waive these provisions if they ultimately believe that a settlement outside Delaware will be a better outcome—so the “exclusive” nature is really an option in the company’s favor. Although slightly more than one half of companies thus have not adopted the provisions, the incidence rate still represents the feature spreading like wildfire, since the provisions have only gained significant attention in the past few years.

Survey Components

Companies Included in Analysis

Anadarko Petroleum Corporation

Andeavor Murphy Oil Corp

Antero Resources Corp.

Apache Corporation

Cabot Oil & Gas Corporation

Cheniere Energy Inc.

Chesapeake Energy Corporation

Chevron Corporation

Cimarex Energy Co.

Concho Resources Inc.

ConocoPhillips

Continental Resources Inc/OK

Devon Energy Corporation Phillips 66

Diamondback Energy Inc.

Dril-Quip, Inc.

EOG Resources, Inc.

EQT Corporation RSP

Energen Corp

Exxon Mobil Corporation

First Solar, Inc.

Gulfport Energy Corp

Halliburton Company

Helmerich & Payne, Inc.

Hess Corporation

HollyFrontier Corporation

Kinder Morgan, Inc.

Marathon Oil Corporation

Marathon Petroleum Corporation

National Oilwell

Newfield Exploration Company

Noble Energy, Inc.

OGE Energy Corp.

ONEOK, Inc.

Oasis Petroleum Inc.

Occidental Petroleum Corporation

Oceaneering Intl. Inc.

PDC Energy Inc

Patterson-UTI Energy Inc

Permian Inc.

Pioneer Natural Resources Company

QEP Resources

Range Resources Corporation

SM Energy Co.

Southwestern Energy Co.

Superior Energy Services Inc.

Targa Resources Corp.

The Williams Companies, Inc.

US Silica Holdings Inc.

Valero Energy Corporation

Varco, Inc.

WPX Energy Inc.

Whiting Petroleum

World Fuel Services Corp.

Not Included—Foreign Incorporated

Core Laboratories N.V.

Ensco PLC

Nabors Industries Ltd

Rowan Companies Plc.

Schlumberger Limited

TechnipFMC plc

Transocean Ltd

Weatherford Intl Ltd

Not Included—Dual Class

PBF Energy Inc

Parsley Energy Inc

SemGroup Corp.

Print

Print