David F. Larcker is James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business and Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on a recent paper by Professor Larcker and Mr. Tayan.

We recently published a paper on SSRN, Scaling Up: The Implementation of Corporate Governance in Pre-IPO Companies, that examines the process by which startup companies implement corporate governance systems.

An effective system of corporate governance is considered critical to the proper oversight of companies. While companies are required to have a reliable corporate governance system in place at the time of IPO, relatively little is known about the process by which they implement it.

At its founding, a typical private company lacks many, if not all, of the features that will later be required by regulatory authorities. The board of directors is composed primarily of insiders—founders, investors, managers—and usually has no directors who meet the independence standards of the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. Financial statements may be subject to an external audit but are usually not prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Financial reporting systems lack many of the controls necessary to comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Compensation contracts are dominated by equity awards and milestone-based payouts whose amounts are not justified in an annual proxy or explained in light of the company’s compensation philosophy, pay objectives, or the peer-group analysis that public companies are required to disclose. And yet, by the time companies go public, they have in place fully established (if not fully matured) systems of corporate governance.

How do pre-IPO companies go from essentially “no governance” at inception to meeting the rigorous standards mandated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to protect the interests of public company investors and stakeholders?

Governance in Pre-IPO Companies

To understand the evolution of corporate governance in pre-IPO companies, we collected data from 47 companies that completed an Initial Public Offering in the U.S. between 2010 and 2018 (see methodology below). We found that pre-IPO governance systems are highly diverse in maturity, rigor, and structure; and that corporate leaders make vastly different choices about when and how to implement the standards required by the SEC in the time leading up to IPO. These choices reflect the individual situations that each company faces in terms of industry, market opportunity, and growth profile, as well as the previous experience of management and investors, funding needs, and speed to IPO.

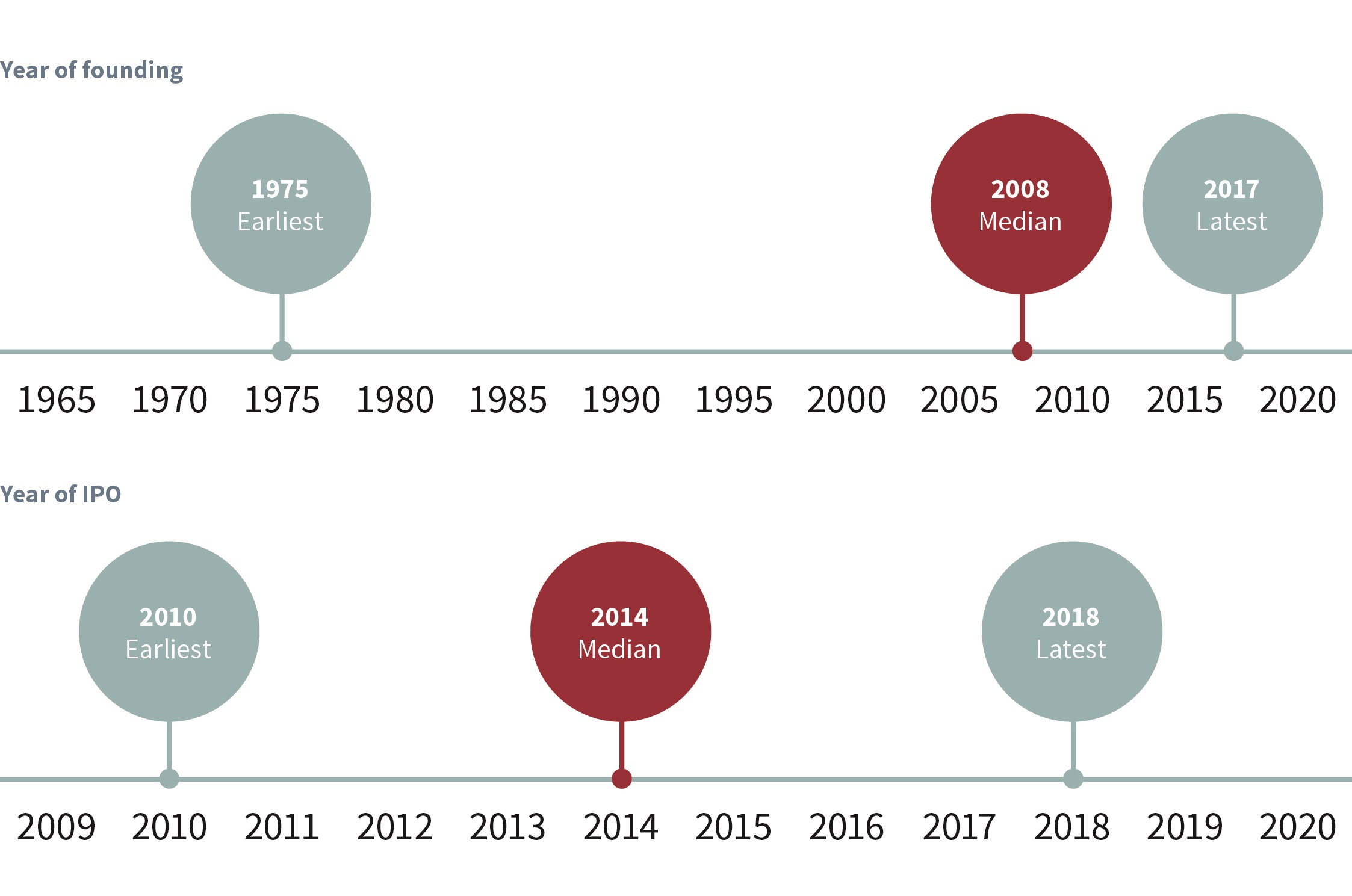

Exhibit 1

On average, the companies in our sample were nine years old at the time of IPO (see Exhibit 1). Major milestones include the following:

5 years prior to IPO

- The company hires the CEO (if different from the founder) who eventually takes the company public.

4 years prior to IPO

- The company implements the financial and accounting systems in place at the IPO.

- The company hires the external auditor used at IPO.

3 years prior to IPO

- The company first becomes serious about developing a corporate governance system.

- The company recruits its first independent, outside board member.

- The company recruits the CFO who eventually takes the company public.

2 years prior to IPO

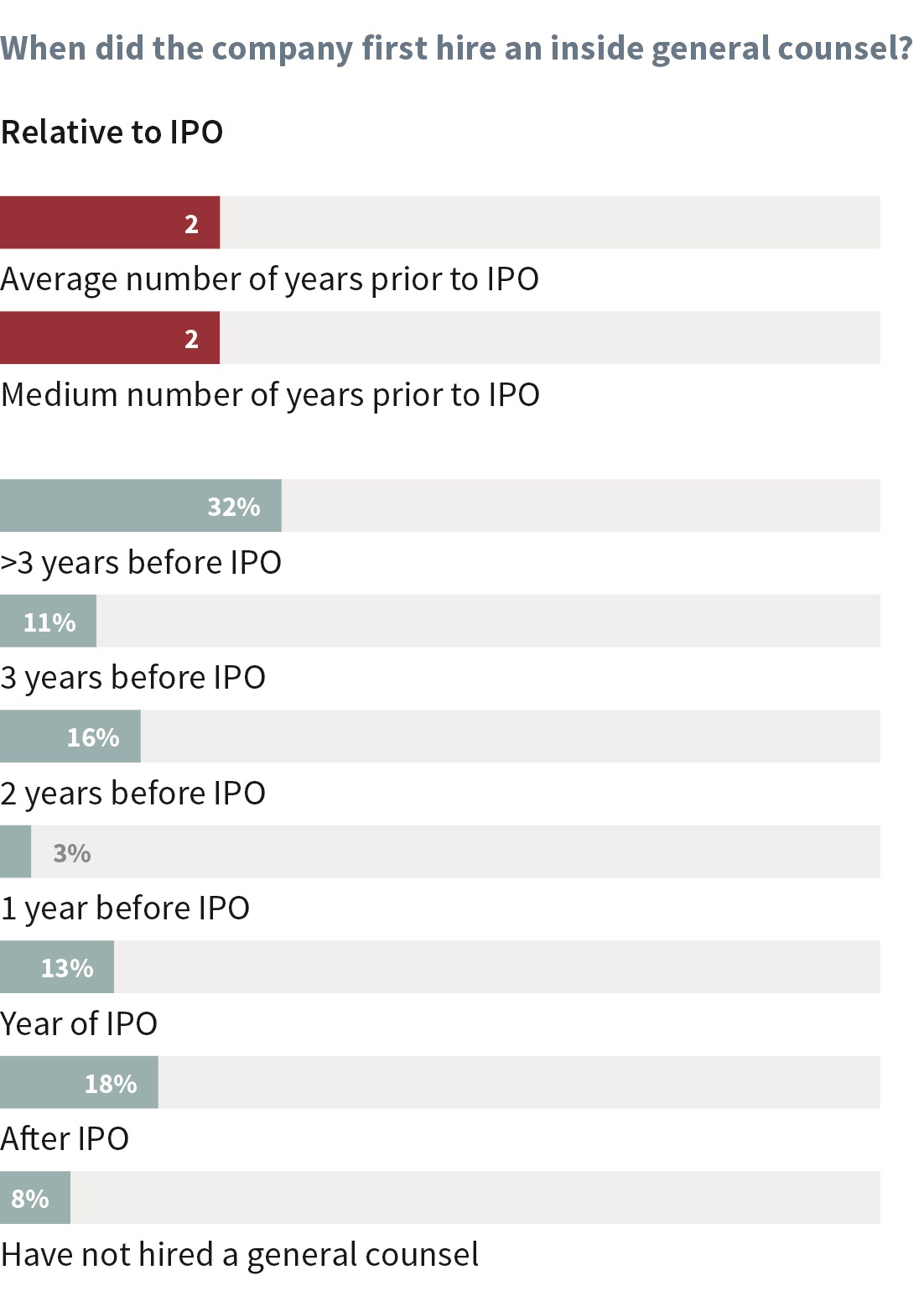

- The company hires an in-house General Counsel.

Note that these numbers are average results (see Exhibit 2). The order in which each event occurs varies widely across individual companies.

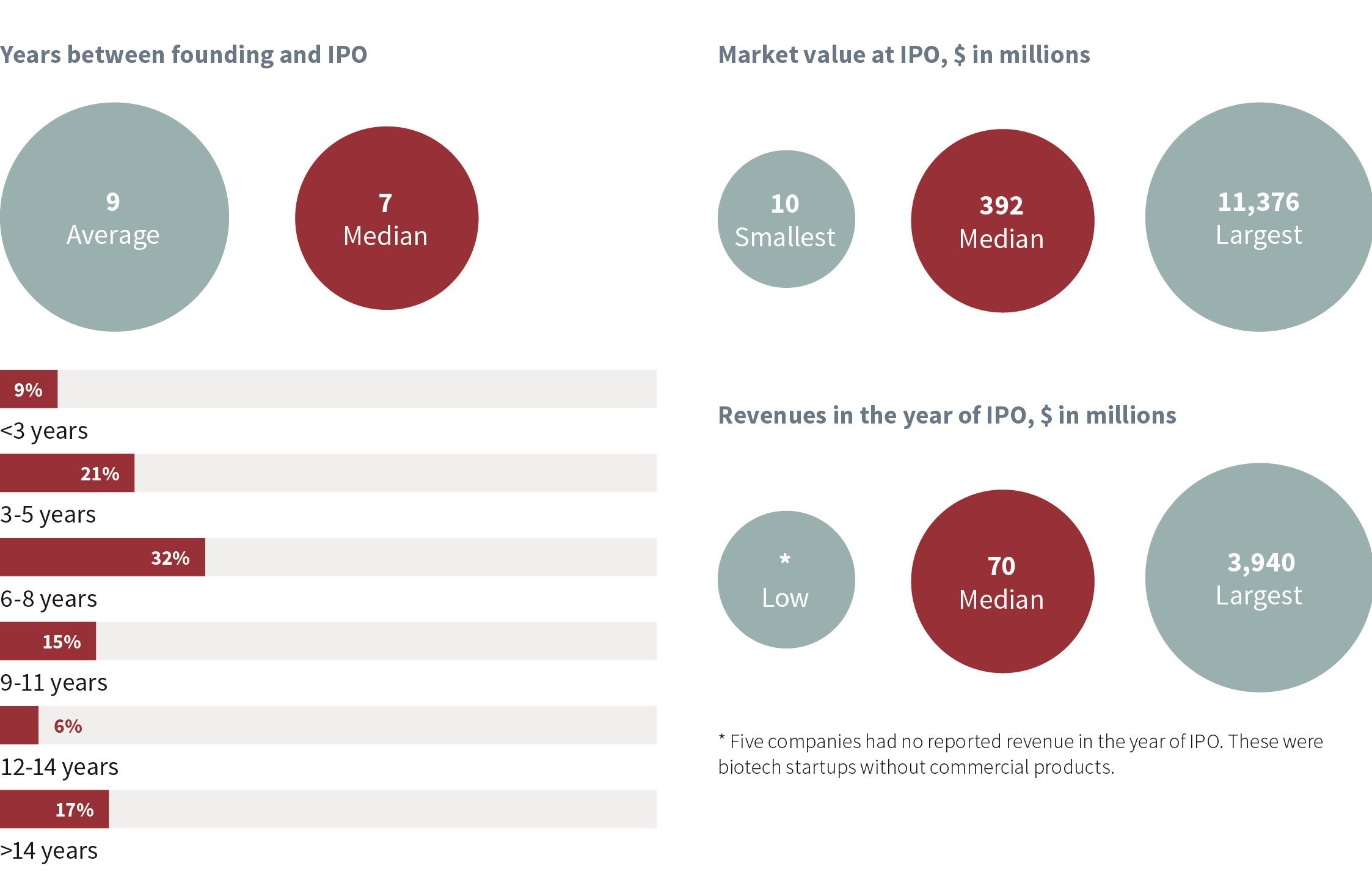

Exhibit 2

Companies that develop governance systems do so primarily as a part of a plan to go public. Eighty-three percent of companies say that they first became serious about developing a system of corporate governance as part of a plan to eventually complete an IPO. Having a corporate governance system is not necessarily seen as a required step in the evolution of a young, private company when the company intends to remain private.

Still, some aspects of corporate governance are embedded in companies from their founding. For example, some companies voluntarily run formal board meetings even at a very young age, some recruit independent directors for their expertise before the company is required to do so, some maintain an independent compensation committee to separate management from the compensation setting process, and some maintain rigorous reporting and internal audit capabilities to assure lenders or customers of the quality of their statements. These practices are adopted for different reasons: a desire to satisfy investors, stakeholders, or regulators; to prepare for eventual scale; or because they are considered “the right thing to do” by the founder, CEO, or major investors.

In the minds of founders and CEOs, “good governance” is synonymous with having independent directors on the board. Companies typically recruit the first independent director to their board at the same time they become serious about developing a system of corporate governance. In interviews, when asked about key steps in developing a formal system of governance, founders and CEOs frequently referred to the decision to add outside experts to the board as the first step they took. Furthermore, the founders and CEOs we interviewed viewed the decision to recruit an independent director as very positive for the company, management, and the board. They cite the value of having people with outside experience to guide leadership as the company grows. According to one founder:

In a privately held company, many times we’re so involved in the day-to-day operations, it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. [Independent directors] have more of an objective view. They see things that management doesn’t see.

Another contrasts the experiences of working with independent directors and working with a venture-capital board:

For VCs, the main questions always center on growth: If you obtain additional capital can you grow quicker? Independent directors tend to focus on whether the right controls are in place, governance factors, the potential risks, and whether we are properly addressing those as the company grows. … One is more growth-based, and the other is more risk management-based.

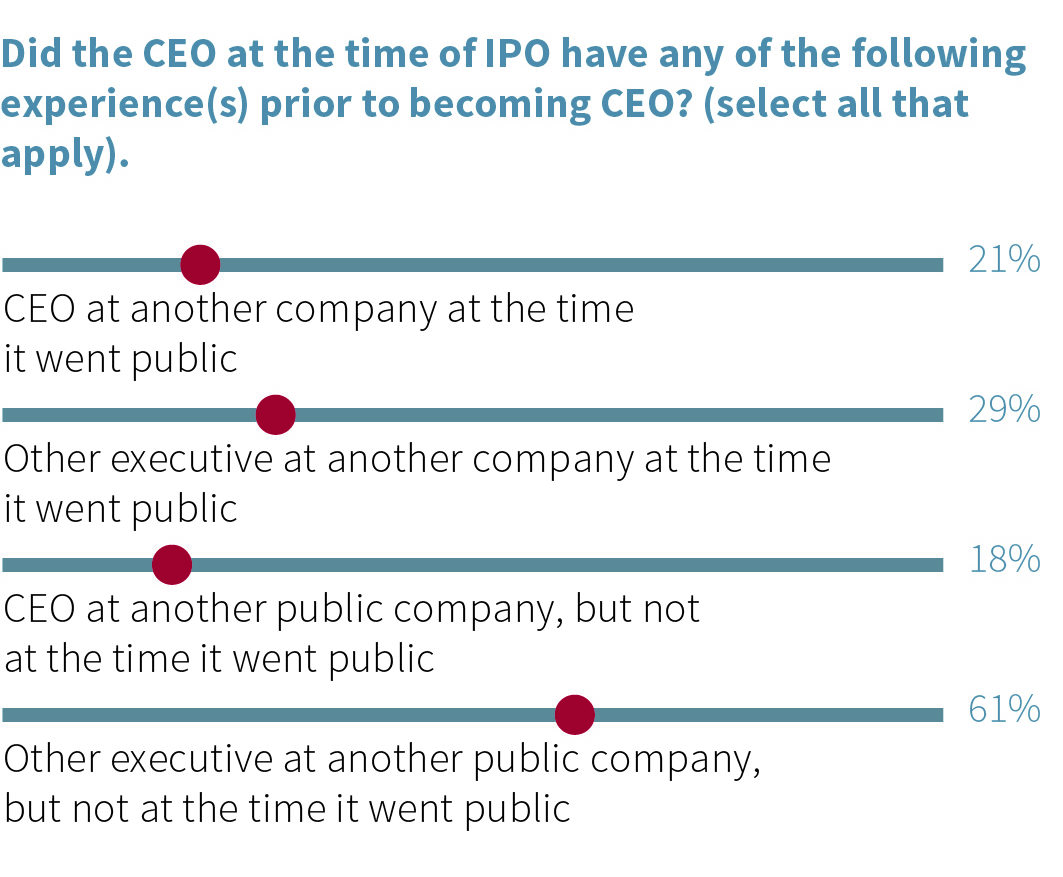

The independent directors that companies recruit have a diverse mix of skills—primarily industry, management, and commercial expertise, but also finance or banking experience, accounting or financial reporting experience, prior board service, or experience growing companies or taking them public (see Exhibit 3). The decision about what skills to look for when adding an independent director for the first time depend specifically on the company’s situation—for example, whether the company is facing growth challenges, expanding into new markets, changing product focus, or implementing more formalized reporting and control functions to support growth or in preparation for an IPO. Independent directors are typically recruited through the personal networks of management and investors. In later stages of growth, private companies rely somewhat more on recruiters. Founders and CEOs are careful to ensure that newly added independent directors, regardless of source, have a positive impact on board culture and dynamics.

Exhibit 3

Seventy-seven percent of companies in our sample had a staggered board at the time of IPO. While staggered boards are considered by some governance experts to be indicative of poor governance quality, no founder or CEO who we talked to said that they received questions from potential investors about their decision to maintain a staggered board. In the words of one CEO:

A lot of companies have a staggered board when they go public. We had no push-back whatsoever. I think that’s almost an expected part of the prospectus. … I never got a question about it at all.

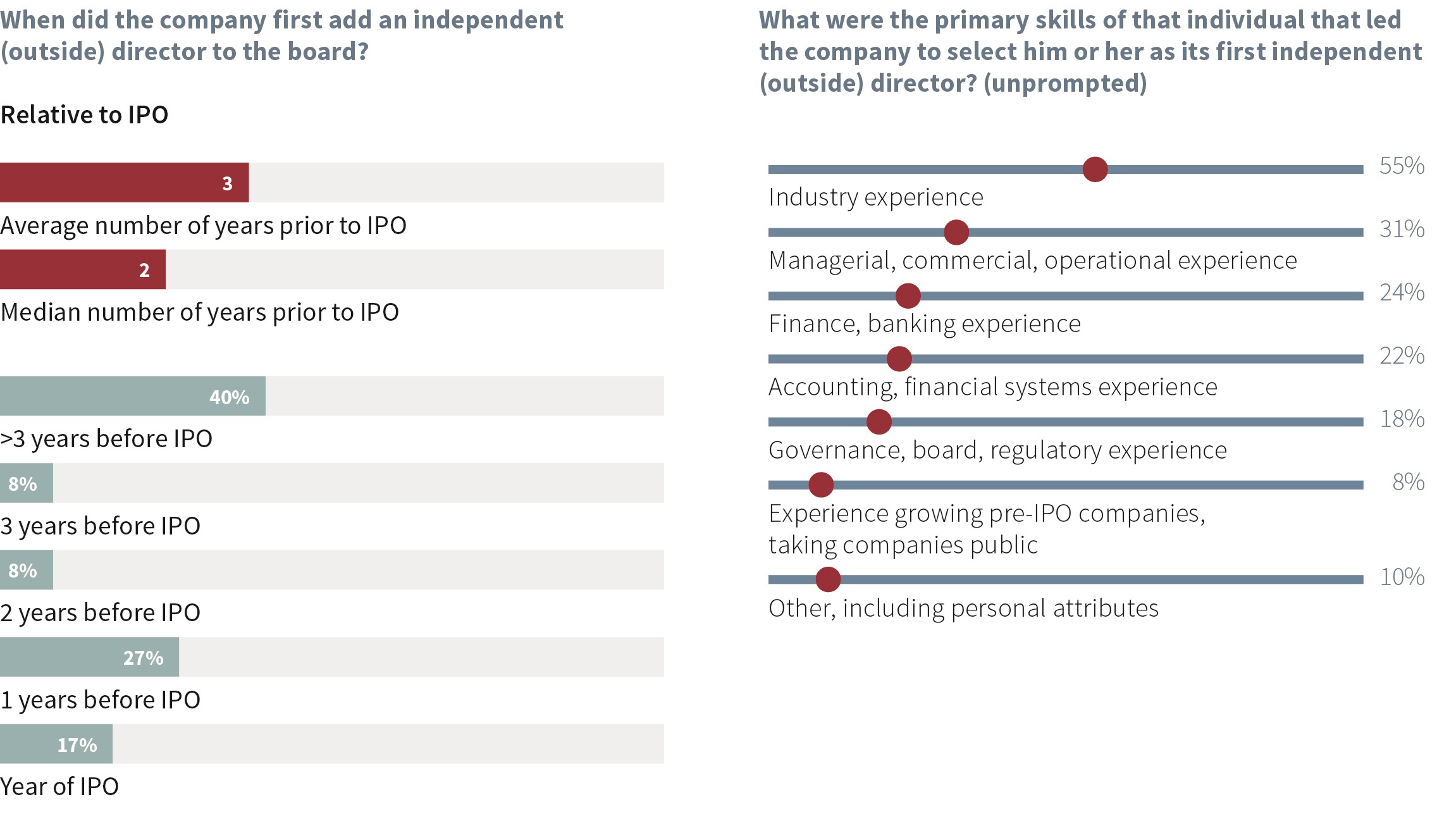

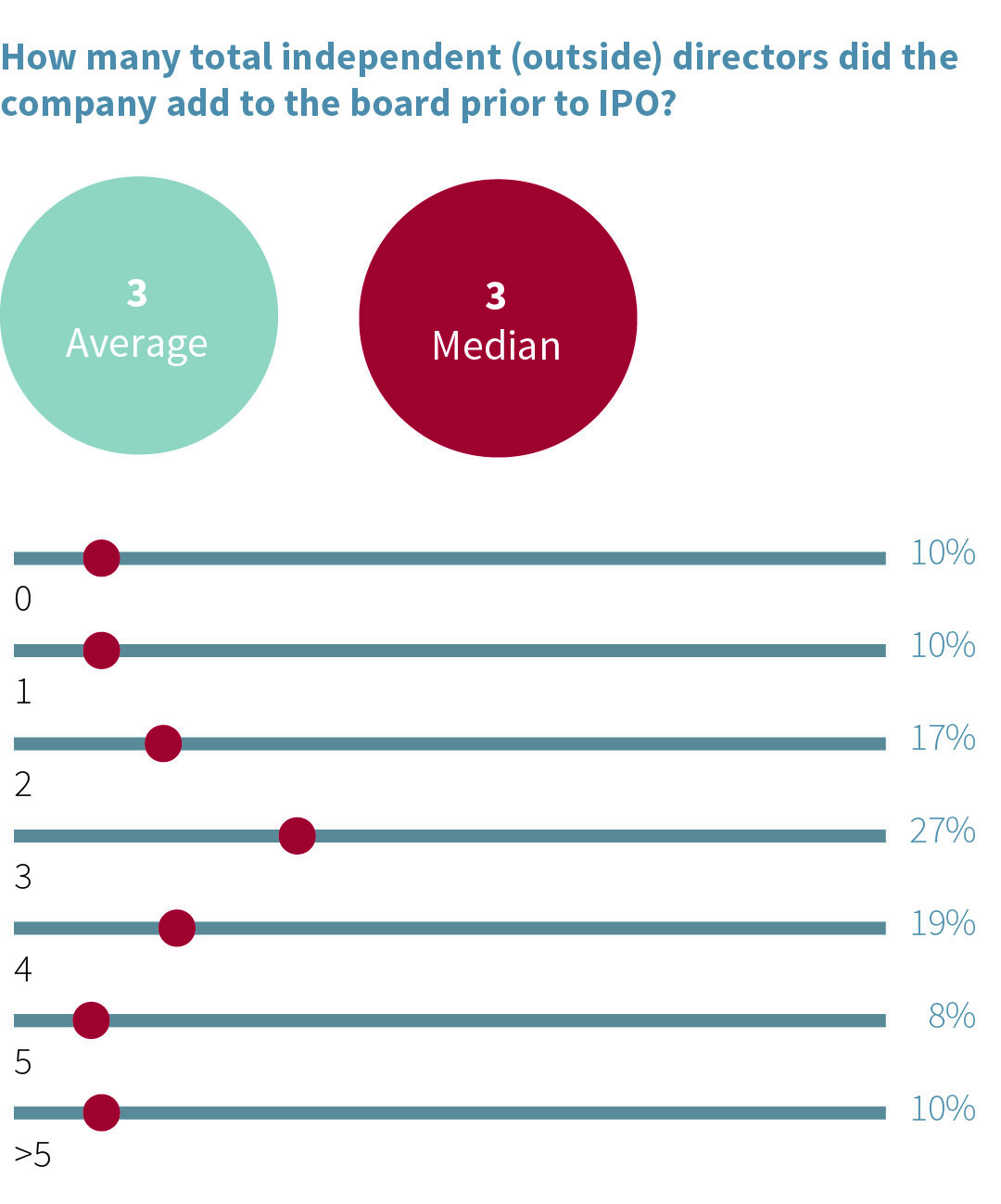

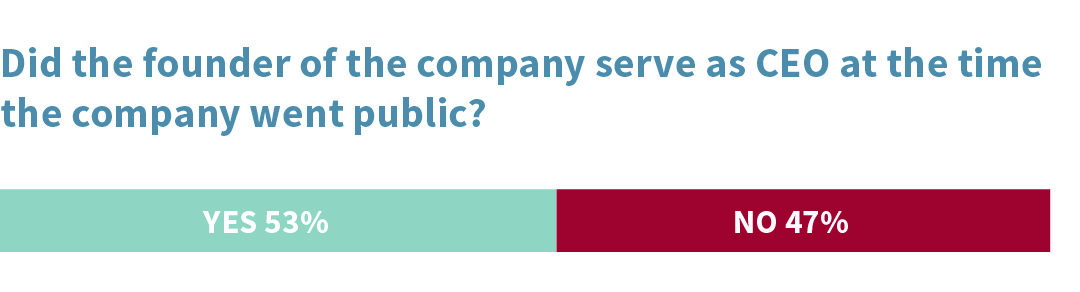

Exhibit 4

Companies in our sample are fairly evenly divided between those whose founders take the company public (53 percent) and those that bring in a non-founder CEO (47 percent—see Exhibit 4). Of note, companies that recruit a non-founder CEO do not do so explicitly in order to take the company public but to scale the company or to solve managerial or commercial problems. One founder provides an example:

The company was struggling when the CEO joined. We were in the midst of trying to implement a pivot in our strategy. … We brought in a new CEO to help, somebody who believed in [our new] approach. He joined us in 2008, and really back then we were just trying to survive, and make this conversion, and we were able to do that. We really didn’t start talking about paths to liquidity until 2013.

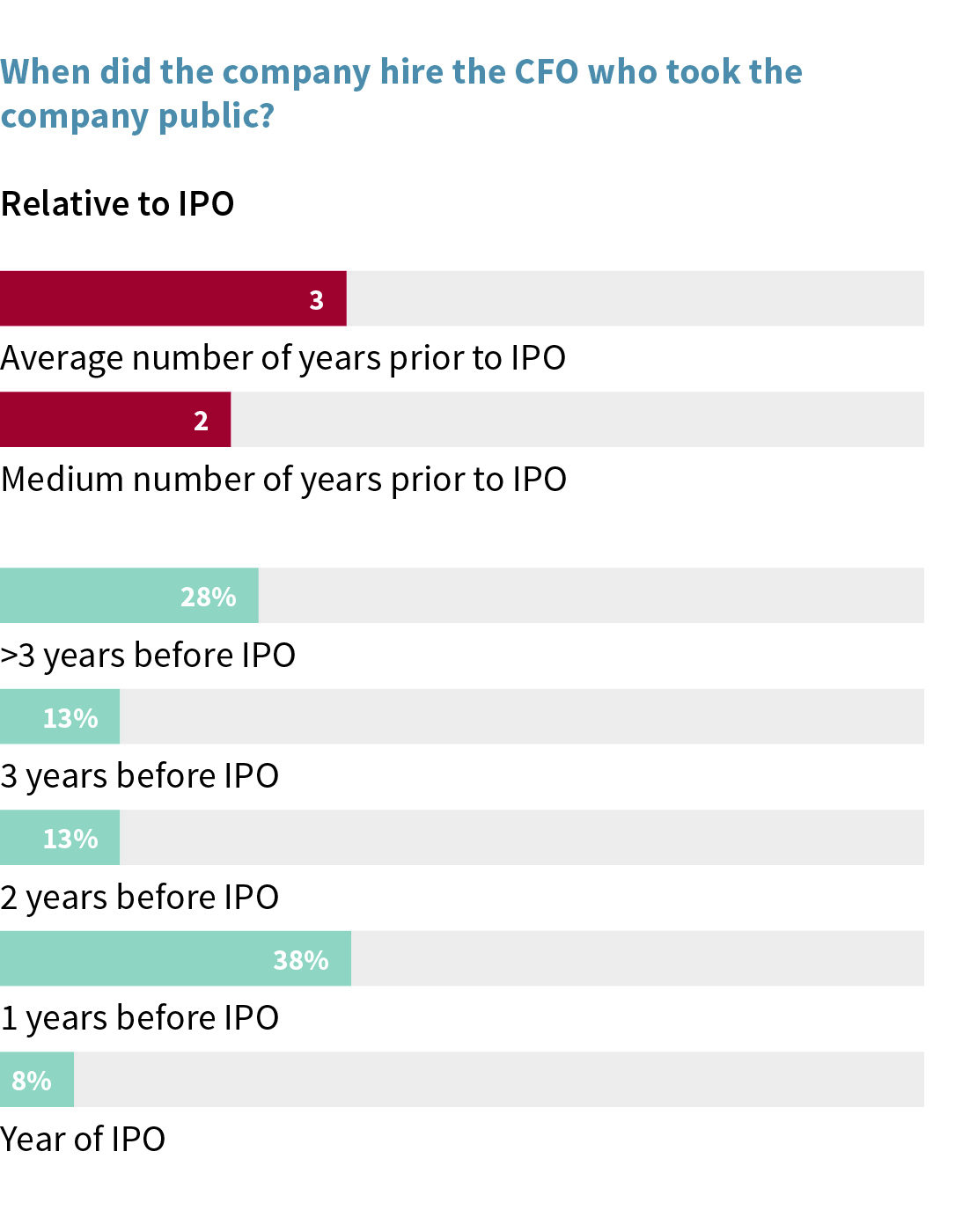

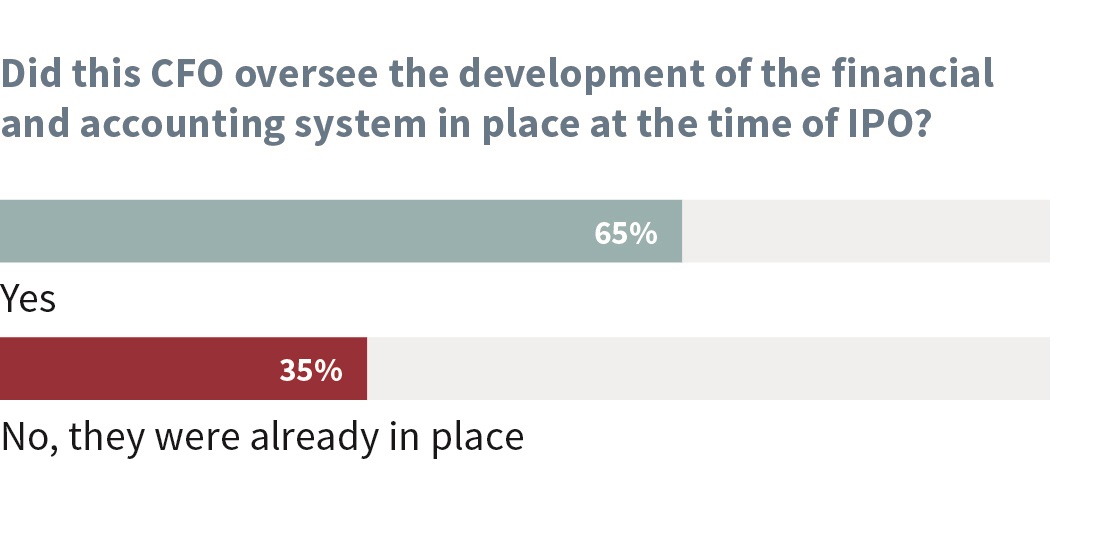

Exhibit 5

Rigorous financial and control systems are put in place to support pre-IPO companies as they scale. The CFO who eventually takes the company public is not necessarily the executive who first implements these systems. In our sample, only two-thirds (65 percent) of CFOs who took the company public were tasked with overseeing the development of the financial and accounting systems in place at the time of IPO (see Exhibit 5). Still, interviews with founders and CEOs underscore the importance, time, and cost of developing these systems to the specifications required by the SEC. Companies whose CFOs did not have deep prior experience running public-company reporting systems were required to bring in experts who have this experience—at the board level, CFO level, or accounting and controls level. In the words of one founder:

We hired a head of internal audit, and he was really critical in getting our SOX controls in place and making sure that we had a sound control environment. … We also hired a person for SEC reporting and technical accounting. We significantly increased the accounting team as part of the going public process because of the large increase in work.

According to another:

We already had gone through the discipline of preparing a clean audited financial statement. Transferring to what was required by the SEC was a big process, there’s no question: There’s more detail, more notes, and other documentation. But the disciplines were in place, and so it wasn’t as difficult as it could have been.

Some founders and CEOs note that provisions of the JOBS Act allowing an emerging growth company to file for IPO before implementing a control environment compliant with Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (as well as being allowed to file confidentially with the SEC) were critical in their decision to move forward with an IPO.

Many pre-IPO companies transition from a regional auditor to a Big Four accounting firm as they prepare for IPO, but a sizable minority do not. Over three-quarters (77 percent) report using a Big Four auditor at the time of IPO. Companies who switch to a Big Four firm do so because they believe their company has become too large and complex for a regional firm.

Exhibit 6

An internal general counsel is considered the “least necessary” element of the governance system in pre-IPO companies. The typical company in our sample hires an internal general counsel two years before the IPO; however, a significant minority (18 percent) do not hire an internal general counsel until after the IPO, and 8 percent have no internal general counsel, even as a public company (see Exhibit 6). The decision to hire an internal general counsel is viewed through a cost-benefit lens. In the words of three different founders and CEOs:

Our decision to hire a general counsel was not driven by regulatory requirements, just volume of work. The fees we were paying to outside counsel were extraordinary. There is an efficiency to having some of it controlled internally, and frankly just having more access to a legal perspective in-house. The person that we hired had been involved in a lot of SEC work in the past, so she had tremendous expertise in dealing with issues that are foreign to the rest of us.

The year after we went public, we decided to bring in an internal general counsel. [Three years later], we reevaluated that decision, and felt that because that individual was not an expert in everything, and they were using a ton of outsourced legal teams to get the work done, we were wasting a lot of money in our legal G&A. We eliminated our internal legal team at the beginning of this year and replaced them with an outside law firm that could bring a higher level of expertise over all aspects of our business, including SEC, corporate board governance, contracting review, licensing, M&A, HR, etc.

Eventually we will hire an internal general counsel. Right now, it is hard to justify the numbers.

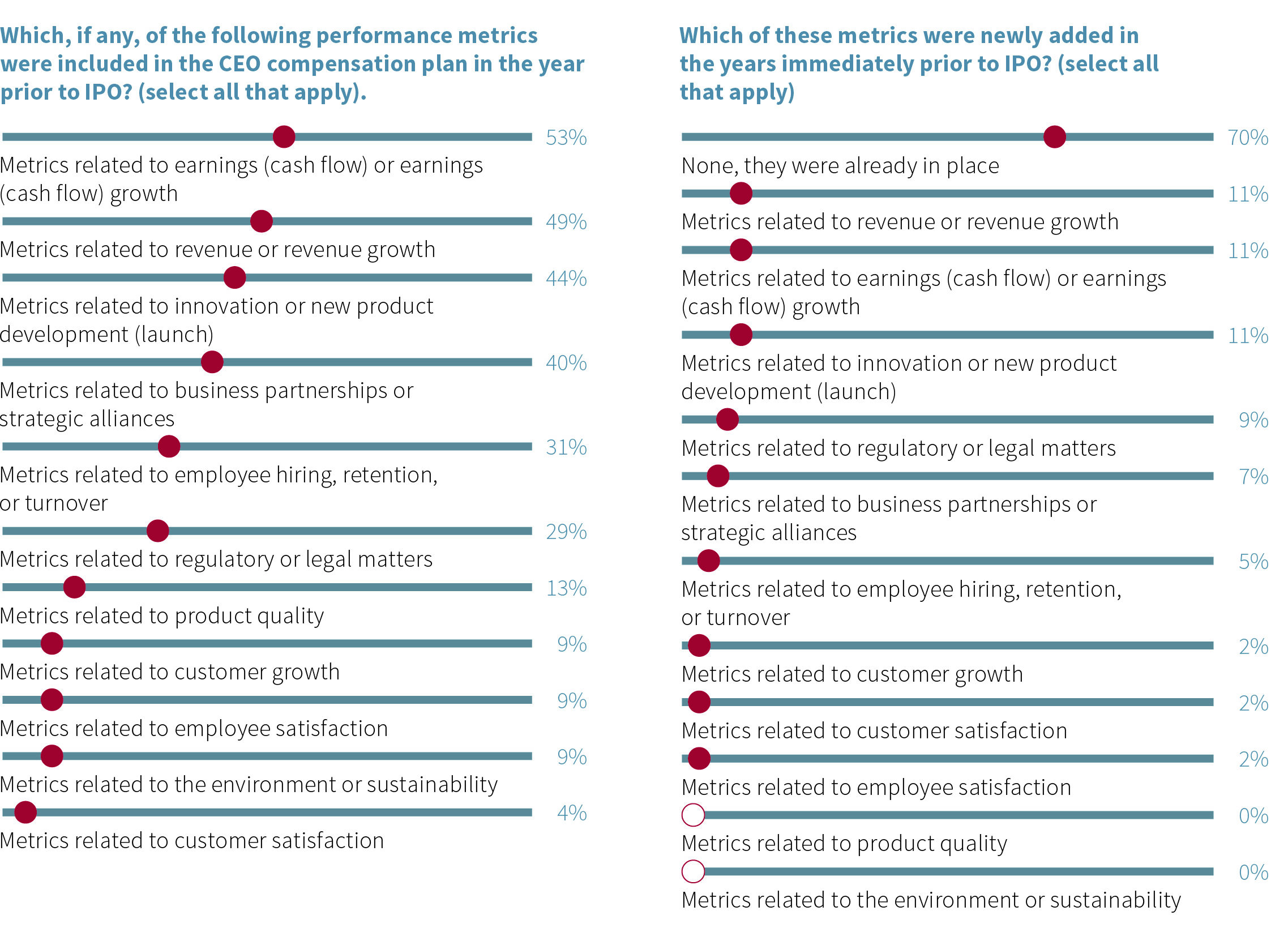

Prior to IPO, companies rely on a variety of key performance metrics and milestone-based targets in awarding CEO bonus compensation. The most commonly used metrics include those relating to earnings and cash flow (53 percent), revenue growth (49 percent), innovation and new product development (44 percent), and business partnership and alliances (40 percent). Other metrics include those relating to employee hiring, retention, or satisfaction; regulatory or legal matters; product quality; customer growth and satisfaction, and sustainability. For the most part, these metrics do not change significantly as the company approaches IPO. Only 30 percent of companies add new performance metrics in the years immediately prior to IPO, and those that do add metrics add ones related to revenue growth, earnings or cash flow, and innovation or new product development (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7

Interviews with founders and CEOs show that companies differ in the degree to which they believe compensation practices change following an IPO. Some take the viewpoint that pre- and post-IPO compensation practices are starkly different: the former reliant on milestone-based awards and stock option grants; the latter reliant on external advice, peer-group assessments, equity burn limits, and a formal disclosure process through the proxy. Others contend that the primary focus in awarding pay does not change: Both pre- and post-IPO pay outcomes depend primarily on achieving growth and performance targets that increase value to shareholders.

Founders and CEOs are generally satisfied with their governance systems. Ninety-one percent of companies are very or somewhat satisfied with the quality of corporate governance system they had in place at the time of IPO. They believe that implementing a governance system that meets the needs of regulators is costly, but recognize that it is a requirement of going public. (Interestingly, few founders and CEOs [12 percent] believe that the quality of their governance system has an impact on the pricing of the IPO, and those who do believe that it does estimate that it contributed 15 percent to the IPO price.)

Finally, they recognize that the systems they currently have in place are not final and will continue to evolve as the company matures in a public environment.

Why This Matters

- There is no one-size-fits-all approach to governance in the pre-IPO world. Companies make vastly different choices on whether, when, or how to implement governance features that are common among public companies. What does this tell us about the relation between governance features and a company’s specific situation? Should regulators and market participants allow public companies greater flexibility to tailor their governance systems to the needs of their business?

- Corporate governance systems in pre-IPO companies are very different and much less developed than those of public companies. The founders and CEOs of pre-IPO companies recognize the value of having a quality governance system in place; at the same time, they recognize its cost. Which elements of governance add to business performance and governance quality? Which have made their way into the regulatory or market environment but do not meaningfully add to governance quality?

- How much value does a good corporate governance system add to a company’s overall valuation? Does good corporate governance impact the IPO price?

- A typical startup company becomes serious about developing a corporate governance system only as part of a plan to eventually complete an IPO. What does this say about the value of corporate governance systems in small or medium sized private companies? When should a small or medium sized company that intends to remain private implement a governance system? Which elements should it include? Which are unnecessary or excessively costly, relative to the potential benefits?

Methodology: Surveys were mailed to the founders and CEOs (at the time of IPO) of 435 companies. Responses were received from 47 companies, representing a 10.8 percent response rate. Respondent companies come from a mix of industries, including biotech and healthcare, technology, services, industrial, real estate, finance and other. In-depth interviews were subsequently conducted with 8 founders or CEOs. For a full summary of the data, see: Rock Center for Corporate Governance, “The Evolution of Corporate Governance: 2018 Study of Inception to IPO,” (2018).

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print