BlackRock, Inc. (“BlackRock”) appreciates the opportunity to comment in connection with the eighth session of the Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC” or the “Commission”) hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century. We welcome the FTC’s Hearings Initiative and efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of competition and consumer protection law, enforcement priorities, and public policy matters in the context of America’s diverse and evolving economy. As an asset manager that invests in thousands of American companies on behalf of our clients, our business benefits from competitive markets and industries. We commend the Commission for prioritizing information gathering and fact-finding to inform its policy efforts.

BlackRock’s comment letter addresses the topics discussed in Hearing #8, “Common Ownership”. Specifically, this letter focuses on the following items from the Hearing Notice: (i) item one, which requests comments on the state of the econometric and qualitative evidence for and against the underlying “common ownership” theories, (ii) item four, which requests comments on potential mechanisms by which concentrated holdings may lead to anticompetitive harm, (iii) item five, which requests comment on institutional investors’ incentive and opportunity to affect corporate governance, and (iv) item six, which requests comment on enforcement and policy responses. We welcome the Commission’s decision to solicit industry views on these important regulatory and policy topics.

Introduction

A nascent academic literature purports to link institutional investors’ positions in more than one firm in a concentrated industry to decreased competition and higher consumer costs. This theory, widely referred to as “common ownership”, has received attention largely based on a single academic paper that purports to demonstrate, on average, a 3-5% increase in the cost of a US domestic airline ticket as a result of “common ownership” (the “AST Paper”). The authors of this paper (“AST”) posit that firms in a single concentrated industry whose shares are owned, in part, by common minority investors maximize industry profits over firm profits, or, at least, that the managers of the competing firms assume this would be their shareholders’ preference and accede to it.

AST have extrapolated their theory about airline ticket prices to argue that “common ownership” effects are present across the economy, stunting competition in a number of different industries and leading to a social cost that accompanies the private benefits of diversification and good corporate governance. The authors ascribe responsibility for this purported effect to asset managers including BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street.

Many academics have voiced deep skepticism about the theory of “common ownership”, which suffers from serious conceptual flaws including a lack of a plausible causal mechanism, incorrect assumptions about control by non-controlling shareholders, and a failure to distinguish the incentives of asset owners from asset managers. In particular, these academics argue that the model applied by AST, which was designed to analyze partial acquisitions of competitors and joint ventures, is not an appropriate model for studying “common ownership”. This is because unlike cross-ownership, “common ownership” involves minority equity ownership interests of thousands of corporate, institutional, and individual investors. Since these investors have varied incentive and governance structures, AST’s uniform assumptions concerning investors’ financial interests and corporate control fail to account for practical and legal realities.

By contrast, other commentators assume the AST Paper’s conclusions are sound, and have proposed remedies to address the supposed problem, including limiting asset managers to one equity position per industry, putting hard limits on managers’ holdings, or prohibiting managers from voting shares. By increasing the cost and risk of diversified investment products, such proposals would undermine households’ access to low-cost diversified investments. Moreover, given the lack of support in the academic literature for the AST findings themselves, the vast majority of studies and most of the panelists who presented at Hearing #8 have concluded that any discussion of policy interventions is extremely premature and not justified by the state of empirical research, which is grounded on highly controversial findings and theoretical research.

The proposed remedies seek to fix a problem that does not exist, and we believe these proposals themselves should be cause for concern. 100 million Americans, or 45% of all US households, own mutual funds; 56% of these households’ mutual fund assets are held in retirement accounts. Implementing the remedies proposed by “common ownership” proponents would constrain the availability of reasonably priced diversified investment products that millions of investors—including pension funds, government institutions and individual retirees—depend on to meet their financial goals. In addition, remedies that involve limiting diversified funds to one company per sector would lead to billions of dollars of divestment from public companies by mutual funds, creating massive flows and generating substantial transaction costs. In accepting as true the hypothetical, marginal harm that the AST Paper has purported to identify, proponents of these extreme remedies recklessly advance an agenda that would have concrete and wide-ranging harm on everyday investors and the economy as a whole.

BlackRock believes that any debate on “common ownership” should be evidence-based and grounded in accurate and robust analysis demonstrating anti-competitive effects, as well as subject to rigorous cost-benefit analysis. To date, the existing research on this topic does not meet this standard.

The remainder of this letter is organized in four parts:

Part I: Describes findings from the replication of results presented in the AST Paper and testing of those results for sensitivities to flawed assumptions. This testing was performed by a third party consultant, Analysis Group, hired by BlackRock. Analysis Group’s findings indicate that the AST Paper’s results do not hold up when incorrect assumptions are corrected.

Part II: Explains index inclusion rules and the implications for treatment of companies during periods of bankruptcy in the AST Paper. Airline company stocks were dropped from the indexes during bankruptcy which is an important methodological flaw in the AST Paper.

Part III: Describes some additional flaws with the AST Paper.

Part IV: Addresses policy measures that have been proposed by “common ownership” proponents.

In addition, we have included an Appendix that corrects the record on factual misstatements about BlackRock made by commentators during the Hearing #8 presentations.

BlackRock has chosen to voluntarily make available the code Analysis Group used to perform the analyses in Part I of this letter. This code builds off the materials released by AST after the publication of their paper in the Journal of Finance in August 2018. A replication package can be downloaded at https://www.blackrock.com/common-ownership. It is BlackRock’s hope that making the code used by Analysis Group publicly available will help ensure the theoretical, policy and legal discussions on this topic are held to the highest academic standards. We invite a full review of the analysis.

Part I: Testing the AST Paper’s results

Notwithstanding the theoretical flaws that have been previously identified by BlackRock and a range of academics, which we believe call into question the theory of “common ownership” itself, AST have recently released to the public information that has permitted BlackRock to engage a third party consultant, Analysis Group, to replicate AST’s results. Analysis Group was able to replicate AST’s results and to test the sensitivities of these results to various methodological choices, or assumptions, made by AST. Analysis Group’s sensitivity analysis reveals that AST’s results are highly sensitive to incorrect assumptions regarding corporate control and financial incentives. We believe Analysis Group’s findings suggest that even the statistical results based on AST’s own model and data are not robust to plausible alternative assumptions.

Specifically, Analysis Group found that correcting for either of the following critical flaws in AST’s assumptions eliminates the statistical significance of AST’s findings regarding anti-competitive effects of “common ownership” :

- “Control” During Bankruptcy: AST assume that equity holders retain “control” rights during bankruptcy. However, equity holders are “last in line” in bankruptcy and do not have control over the company during bankruptcy periods. During bankruptcy, companies do not hold annual meetings and there is no venue for shareholders to vote. Even AST acknowledge that assuming equity holders have control in bankruptcy runs counter to the realities of equity ownership in bankruptcy. When this flaw is corrected, the AST Paper’ s result s are no longer statistically significant.

- Differing Financial Incentives: AST assume that all institutional investors have the same economic interests in their shareholdings in public companies. This assumption fails to recognize the most basic difference in economic interests between asset managers and asset owners. Asset managers act as fiduciaries on behalf of their clients and earn a small management fee on the total amount of assets they manage. Asset managers invest in thousands of companies across the entire market and do not have meaningful economic interests in the performance of any individual company. When the differences in economic interests of asset managers and asset owners are properly reflected, the AST Paper’ s results are no longer statistically significant.

When the aforementioned erroneous assumptions are corrected, Analysis Group finds no statistically significant relationship between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices. We believe these findings suggest that the results presented in the AST Paper are not robust to even small changes in assumptions. At the very least, the AST paper should not be used as the basis for formulating policy decisions by the FTC or any other agency given the unreliability of the findings. A memo with information that can be used to replicate Analysis Group’s results used in forming these conclusions is publicly available at https://www.blackrock.com/common-ownership.

A. Background on AST Paper Methodology

Drawing on economic research evaluating “cross-ownership” between firms (e.g., a joint venture between competing firms), AST use an economic measure that augments standard measures of industry concentration to account for the effects of “common ownership”. AST claim that this measure, referred to as “MHHI Delta”, accurately captures the impact of “common ownership” on competition.

As used by AST, MHHI Delta reflects two components of an investor’s ownership in competing firms. The first is the investor’s right to vote in corporate decisions in the firm, which captures its extent of “corporate control”. The second is the investor’s rights to a share in the profits of the firm, which captures its “financial incentives” AST assume that both of these terms are directly proportional to the fraction of total shares held by each investor for each quarter of the period they study. Furthermore, they do not account for any relevant effects that bankruptcies can have on investors’ ownership and control rights. The following two subsections will show that these two incorrect assumptions drive the statistical significance of AST’s results, and when they are corrected, the AST Paper’s results are no longer statistically significant.

B. Testing Sensitivity of “Control” Assumption During Bankruptcies

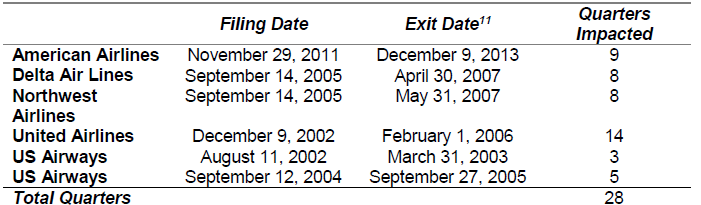

The AST Paper purports to analyze corporate control of airlines using a measurement period when three of the four major airlines—AMR Corp. (“American Airlines”) (2011-2013), Delta Air Lines, Inc. (“Delta Air Lines” (2005-2007), and UAL Corp. (“United Airlines” (2002-2006)—experienced extended bankruptcies. Other major airlines and smaller airlines also experienced shorter bankruptcies during this period. Exhibit 1 shows that during 28 of the 56 quarters (or 50%) covered by the AST Paper’s sample, at least one major US airline was in bankruptcy.

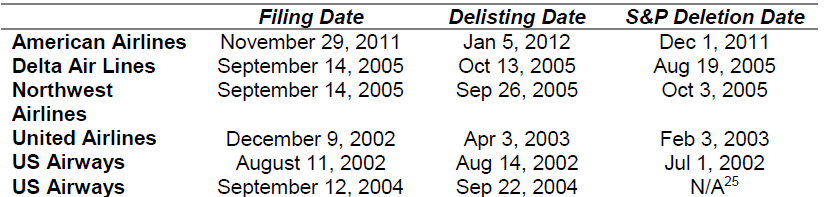

Exhibit 1: Dates of Bankruptcies of Major Airlines in the US

Note: Number of quarters do not sum to total because of overlap between quarters.

Source: AST data production.

Despite this important characteristic of the measurement period and sample analyzed, the AST Paper utilizes simplifying assumptions that AST acknowledge are not in line with reality. Specifically, the AST Paper assumes that shareholder control and financial incentives are unchanged when an airline enters bankruptcy, and remain constant at pre-bankruptcy levels throughout the entire course of the bankruptcy. As we will discuss in Part II, this assumption is particularly incorrect for index fund managers because bankrupt companies are removed from equity indexes, causing index funds to sell their shares at or shortly after the bankruptcy filing date. In other words, the AST Paper assumes index fund managers had “control” over the bankrupt companies when, in fact, they did not even own shares in those companies at the time of bankruptcy.

Putting this fundamental issue aside for the moment, assuming equity holders have “control” of a company that is in bankruptcy defies legal and practical realities. When a firm files for bankruptcy protection under US law, the company’s executive managers are under an obligation to act first in the best interest of the firm’s creditors and not of equity holders. Equity holders are “last in line” to receive cash flows from the bankrupt firm, and thus any influence equity holders may have had over management pre-bankruptcy is substantially reduced or eliminated during bankruptcy. The rights of secured and unsecured creditors are prioritized over equity holders by law, and equity holders typically only receive compensation or regain their rights to cash flows once all creditors have been adequately compensated. Pre-bankruptcy shareholders typically have no voting rights once a firm enters bankruptcy protection. Importantly, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines and United Airlines did not hold a single shareholder meeting during the period they were in bankruptcy protection, giving their equity holders no formal venue to even attempt to exert influence.

AST appear to recognize their flawed assumption, as they note that “[b]ankruptcies may confound the results because shareholders have no de jure control rights during such times, and this feature is not captured in our computation of MHHI delta.” In fact, contrary to AST’s simplifying assumption that control continues throughout the bankruptcy period, the impact of bankruptcies on corporate control during the 28 quarters when airlines were in bankruptcy can easily be incorporated into the analysis by setting shareholder control rights during these periods to zero. Doing so reflects AST’s own intellectual concession that equity holders have no de jure control rights during bankruptcy.

AST claim to have controlled for this incorrect assumption regarding bankruptcy by running placebo and robustness checks. While AST conclude that their “results are generally weaker in markets and at times affected by bankruptcies,” we believe the checks they conducted were insufficient to validate their main results. AST thus fail to incorporate the actual control rights present during bankruptcy periods.

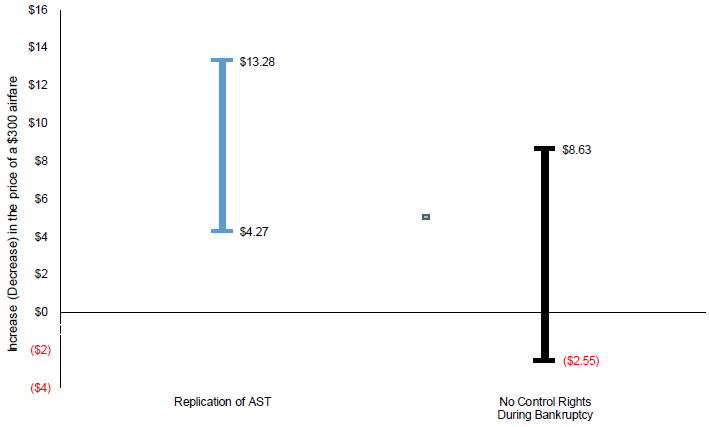

To test the sensitivity of the AST Paper’s results to this assumption, Analysis Group incorporated this adjustment into the AST methodology. After adjusting for the lack of equity holder control during bankruptcy, the association between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices across the entire study period of the AST Paper is not statistically different from zero. Exhibit 2 illustrates the weakness of the results when control rights are treated correctly. The ranges described by the bars in this exhibit represent the 95% confidence interval around the respective estimates. While the midpoint (i.e., the point estimate) of the right-most bar is positive, the confidence interval includes zero, which means that the estimate is statistically indistinguishable from zero, invalidating AST’s conclusions.

Exhibit 2: Estimated Range of the Effect of “Common Ownership” on a $300 Airfare

Range reflects a 95% Confidence Interval

Note: Results from market-carrier level regressions.

This critique of the AST Paper has been raised before in an academic paper that called into question AST’s results. However, AST dismissed these criticisms largely on the basis that those academics were unable to fully replicate the AST Paper’s baseline results without access to the original code and data. The same cannot be said of the analysis presented in this letter, which is based on the actual code and data from the AST replication package. As the AST Paper’s purported correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices loses statistical significance once this rudimentary correction for bankruptcy periods is made, this analysis demonstrates that the AST Paper’s results are not robust.

C. Testing Sensitivity of Assumption of Equivalent Economic Interests of All Institutional Investors Given Differences between Asset Managers and Asset Owners

While the interests of asset owners and asset managers are generally aligned, the AST Paper incorrectly accounts for the different financial incentives that different types of institutional investors have. Specifically, the AST Paper incorrectly assumes that asset owners and asset managers have identical financial incentives. The authors’ reliance on regulatory reporting data ascribes a financial interest that is directly proportional to the amount of shares reported, regardless of whether the reporting entity is an asset manager or asset owner. In reality, asset managers have substantially less financial interest in the portfolio companies held by funds they manage than the shareholders of those funds. While asset owners are the direct beneficiaries of the gains and losses generated by shares they own, asset managers are paid a management fee—as small as a few hundredths of a percent—based on the aggregate value of assets under their investment discretion. Thus, asset owners’ financial interest reflects the full change in market value of their shares in the company, while asset managers’ direct financial interest is necessarily limited to the management fees they earn. By ignoring differences among different types of shareholders’ financial incentives, the AST Paper overestimates “common ownership” concentration.

To illustrate this point, consider a $1 million investment in a publicly-traded company’s stock. If this position were held in an index fund managed by an asset manager that charges a 5 basis point management fee (i.e., 0.05%), an increase in the company’s share price of 1% would provide the advisor with $5 in additional fees. By contrast, an individual asset owner holding the position directly would realize a $10,000 gain on their investment. The asset owner’s financial incentive in this example is 2,000 times larger than the asset manager’s incentive.

As an aside, this example assumes that the 1% share price increase of an individual equity position has a proportionate positive impact on an investor’s overall portfolio value. However, depending on the source of incremental profit, this is not always the case. Consider the effects of an increase in airline ticket prices alleged by AST: a broad based index fund that holds securities of companies in a diverse array of industries, airlines being only one of many, may experience a net negative impact from an increase in airline ticket prices because higher airline ticket prices increase the travel expenses incurred by other companies in the portfolio. As Exhibit 3 demonstrates, airlines represent less than 1% of the most frequently used equity indexes.

Exhibit 3: Weighting of Airlines in Equity Indexes

| Index |

American |

Delta |

United |

Aggregate |

| S&P 500 |

0.09% |

0.15% |

0.07% |

0.31% |

| MSCI US Large Cap 300 |

0.12% |

0.19% |

0.09% |

0.40% |

| FTSE RAFI US 1000 |

0.03% |

0.05% |

0.04% |

0.12% |

| FTSE USA |

0.03% |

0.04% |

0.02% |

0.08% |

| MSCI USA |

0.03% |

0.04% |

0.02% |

0.08% |

| Russell 1000 |

0.09% |

0.13% |

0.07% |

0.28% |

Source: Index weightings from S&P, MSCI, FTSE, Russell, retrieved from BlackRock Internal Data Systems, November 2017.

Because they are compensated by management fees, asset managers’ greatest financial incentive is to compete with other asset managers on the basis of relative investment performance (net of fees) and client service. Index fund managers demonstrate relative performance by most closely tracking the index. Since index funds hold more or less identical portfolios of companies, encouraging an increase in the price of one company or sector has little effect on relative performance. Indeed, even actively managed funds must be “overweight” a stock or a group of stocks compared to competing funds for their relative performance to benefit from higher equity returns of a given company or sector. As such, encouraging an increase in prices of a single company or sector has very limited benefit to asset managers of diversified portfolios relative to their primary commercial interests.

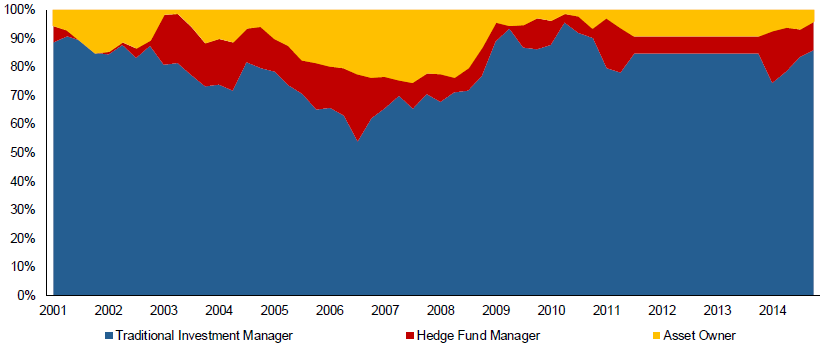

The incorrect assumption that asset owners and asset managers have identical financial incentives impacts a large portion of the ownership data included in the AST Paper’s analysis, as 75-85% of shares during any given quarter of AST’s analysis are managed by traditional investment managers of diversified portfolios (such as BlackRock, Capital Group, Fidelity, State Street Global Investors, T.Rowe Price, and Vanguard), as shown in Exhibit 4 below.

Exhibit 4: Scaled Percentage of Total Shares by Investor Type

American Airlines

2001–2014 quarterly data

Notes:

[1] Following AST, data on shareholdings are sourced from Thomson Reuters Spectrum, AST’s manually collected SEC Form 13F filings, and AST’s manually collected proxy statements. Further, share counts are aggregated across separate entities. (See AST, p. 16, fn. 10).

[2] The data does not include owners with equity holdings smaller than 0.5%.

[3] Ownership type is defined by S&P Capital IQ. Asset owners include government pension sponsor, family offices/trust, bank/investment bank, charitable foundations, individuals/insiders, non-institutional, and unclassified investors.

Sources: AST Replication Package; Thomson Reuters Spectrum.

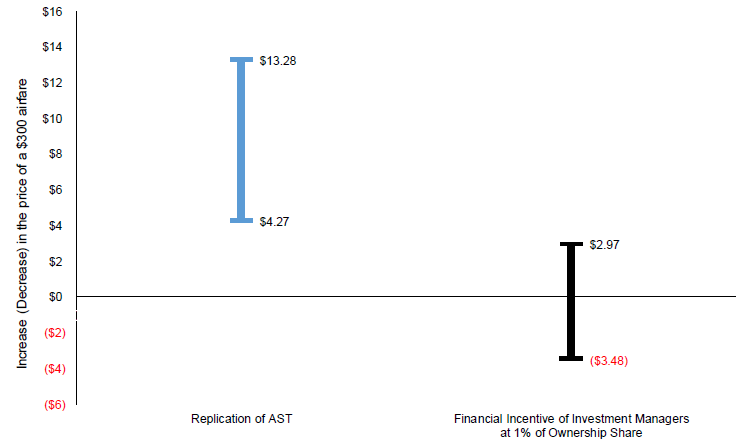

In order to test whether AST’s overstatement of the financial incentives of traditional asset managers affects the results presented in the AST Paper, Analysis Group replicated the AST Paper’s regressions (again, using the AST Paper’s data and code) but instead of assuming equivalent economic interests for all institutional investors, Analysis Group adjusted asset managers’ financial incentive to be 1% of their ownership share. 1% is meant to reflect a more realistic estimate of the economic interest in the company that an asset manager would have due to its investment management fee. 1% is a conservative overestimate given that investment management fees on US equity investment products are typically much lower than 1%. For example, expense ratios of three US Large Capitalization Stock ETFs offered by three different providers are between 0.03% and 0.0945%. For actively managed products, Reuters recently reported that the asset-weighted average expense ratio of actively managed equity mutual funds fell from 1.08% of assets managed in 2001 to 0.86% in 2014. Management fees are only a subset of a mutual fund’s total expense ratio. During the AST Paper’s period of study, management fees for mutual funds were typically no greater—and often much less—than 1%.

The same article shows the asset-weighted average expense ratio of passively managed (index) equity mutual funds fell from 0.25% in 2001 to 0.11% in 2014.

After adjusting for asset managers’ financial incentives, Analysis Group found that the correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices is not statistically different from zero, as is illustrated in Exhibit 5 below. As such, the AST Paper’s test of the correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices is not robust to this minor correction.

Exhibit 5: Estimated Range of the Effect of “Common Ownership” on a $300 Airfare

Range reflects a 95% Confidence Interval

Note: Results from market-carrier level regressions.

Part II: Index Inclusion Rules and the Treatment of Companies during Periods of Bankruptcy

As noted in Part I assuming that index fund managers had “control” over airlines when they were in bankruptcy is incorrect. In their paper, AST assume that asset managers’ equity holdings in airlines remain constant for the duration each airline is in bankruptcy and “repeat the last observed value for percentage of shares owned” in bankrupt airlines.

This assumption is grossly inaccurate at least in the case of index fund managers (and likely for a portion of active managers as well) and reflects a lack of understanding of index construction rules. Index providers such as S&P Dow Jones and Russell Investments remove companies in bankruptcy protection from their indexes concurrent with or before the bankruptcy filing date and the de-listing of the issuer’s equity from a stock exchange. Given their objective is to track the index, index funds sell their shares in bankrupt companies at or shortly after the bankruptcy filing date. Exhibit 6(a) shows that all major airlines in the US were removed from S&P indexes during their respective bankruptcies. Exhibit 6(b) shows that airlines were added back to S&P indexes after they emerged from bankruptcy, only when they could meet the criteria for reinstatement.

Exhibit 6(a)—Bankruptcy Filings of Major Airlines and Deletion from S&P Indexes

Source: SEC filings and S&P announcements.

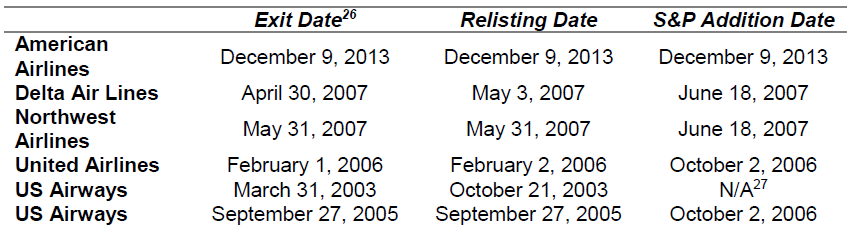

Exhibit 6(b)—Bankruptcy Exits of Major Airlines and Reinstatement to S&P Indexes

Source: SEC filings and S&P announcements.

For example, the overwhelming majority of holdings in portfolios managed by BlackRock in the major US airlines prior to their respective bankruptcy filings were held in index funds. BlackRock therefore sold nearly all of its holdings upon each airline’s bankruptcy filing, and did not repurchase shares until each airline had been reinstated to the relevant index. This reality of index management leads to significant differences between the shareholdings attributed to BlackRock in the AST Paper and the amount of shares actually held by BlackRock-managed portfolios during the AST Paper’s study period.

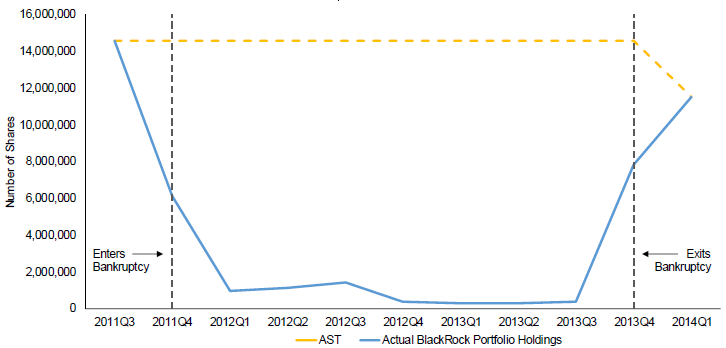

Exhibit 7 provides an example of the size of this discrepancy during the period when American Airlines was in bankruptcy.

Exhibit 7: BlackRock Equity Holdings

American Airlines

2011Q3–2014Q1

Notes:

[1] The “AST” line is sourced from Thomson Reuters Spectrum and AST’s manually collected SEC Form 13F filings. Share counts are aggregated across separate BlackRock entities. Shares from 2011Q3 are “forward-filled” for the bankruptcy period.

[2] The “Actual BlackRock Portfolio Holdings” line for 2011Q–2013Q4 is sourced from BlackRock’s internal data systems and includes shares in American Airlines that would be reported in SEC Form 13F by any of BlackRock’s entities. For quarters outside of the bankruptcy period, the values of the “Actual BlackRock Portfolio Holdings” line are the same as the “AST” line.

Source: AST Replication Package; Thomson Reuters Spectrum; BlackRock Internal Data Systems.

Part III: Additional Theoretical Flaws with AST Paper

The fundamental shortcomings specified in Part I are premised on acceptance of the AST Paper’s data and methodologies. However, in the course of replicating the AST Paper’s results, Analysis Group identified several other data and methodological issues with the AST Paper. While a comprehensive investigation of each of these issues is beyond the scope of this letter, future empirical research should evaluate the impact of correcting for the flaws described below.

A. Flawed Reliance on Threshold Reporting Data

The AST Paper measures “common ownership” using Form 13F disclosures filed by asset managers. Form 13F is a quarterly SEC filing in which institutional investors with investment discretion over $100 million in exchange-traded equity securities provide a snapshot of their holdings. While Form 13F data is intended to provide a degree of visibility into institutional investor holdings, it provides an incomplete picture of investors’ total economic exposure and voting rights, and does not provide a complete picture of a company’s shareholder base.

Institutional investors interpret the SEC’s Form 13F instructions and guidance differently, leading to inconsistencies in how holdings are reported. For example, some large asset managers who have a robust internal proxy voting function interpret the 13F rules as requiring them to report having no voting authority over such shares. This is a critical point, as the AST Paper claims to only count as “control shares” those positions over which an asset owner or manager reports having “sole” or “shared” voting authority on its 13F reports. The AST Paper does not appear to correct for inconsistencies in how different asset managers report holdings on Form 13F.

Along with the problems inherent to Form 13F data, the AST Paper relies on a version of Form 13F aggregation data provided by Thomson Reuters Spectrum, which has numerous known flaws. While the AST Paper purports to correct for missing filings, the ownership data in the Journal of Finance replication package indicates that the authors’ efforts to correct the dataset are incomplete. Flaws in the underlying ownership data are especially troubling because the AST Paper’s key explanatory variable, MHHI Delta, is extremely sensitive to missing data.

B. Failure to Follow Academic Conventions in Working with Airline Ticket Data

Since the domestic airline industry was deregulated in the late 1970s, airline competition has been a subject of keen academic interest. Over time, extensive literature has developed conventions and best practices for analyzing the publicly available ticket data that the AST Paper relies on. The literature analyzing competition among airlines has long recognized that airline tickets, even for a particular route, vary due to the number of stops, number of plane changes, and fare class, among other considerations. Researchers typically filter the ticket data to eliminate itineraries with more than one (or an unknown) operating carrier, one or more stops, and first and business class tickets, in order to create a homogenous sample of tickets for purposes of direct comparisons across markets and over time. The AST Paper fails to employ these well-established methodologies, potentially biasing its results.

C. Mischaracterizing Incentives and Conduct of Airline Management

The AST Paper assumes that airline management internalizes and bases management decisions upon holdings data not only of their own shareholders, but also of shareholders of all of their competitors. This assumption is implausible for several reasons.

First, and most fundamentally, this assumption would mean that executives of a particular airline are willing to sacrifice their company’s profits to advance the purported objectives of a subset of their shareholders who are common holders of competitors. Doing so would be in direct violation of their fiduciary duties to the company.

Second, these same executives would be sacrificing their own personal financial interests. Senior airline executives receive a portion—or even all—of their compensation in company stock.

Third, accounting for their “common owners’ interests would require airlines to have up-to-date knowledge of their shareholders’ entire investment portfolio, as well as access to data on the entire investment portfolio held by each institutional shareholder’s clients across their portfolios. We believe it would be difficult to obtain this data if not impossible given that many institutional investors’ holdings are not publicly available.

D. Failure to Account for Proxy Advisory Firms

The AST Paper fails to account for the important influence of third party proxy advisors, which wield substantial influence over the outcome of shareholder votes. Surveys indicate that 60% of institutional investors rely on proxy advisors in making voting decisions. The mechanical reliance by some investors on proxy advisors’ recommendations creates a voting bloc that reliably votes in parallel. One study estimates that a negative recommendation by Institutional Shareholder Services led to a 25% reduction in say-on-pay support by shareholders. By comparison, asset manager voting has been demonstrated to vary from firm to firm. While the influence of proxy advisory firms is well known in the asset management industry, their role and influence is not accounted for in the AST Paper. This omission is important as AST claims much smaller holdings by asset managers are influential.

E. No Causal Mechanism Has Been Established

The AST Paper fails to substantiate a plausible mechanism for the anticompetitive effect it claims to find. The AST Paper proposes three possible causal mechanisms: (1) asset managers fail to actively encourage competition between their portfolio companies; (2) asset managers discourage competition through investment stewardship engagements; and (3) large index fund positions reduce the likelihood of activist campaign success. AST are wrong in all three respects.

AST’s first argument supposes that firm management lacks incentives to compete without shareholder pressure. Executive compensation reflecting firm performance through equity rewards and future employment prospects based on past successes both serve as strong incentives for managers to compete. Moreover, AST’s theory proposes a false choice between shareholders actively demanding more competition and shareholders acting anti-competitively. The idea of the “quiet life” that AST take from the literature on corporate governance does not propose such an idea.

AST’s second argument is based on a misunderstanding of asset manager investment stewardship. In the normal course of business, most traditional asset managers such as BlackRock do not meet with boards of directors and management teams of public companies to provide direction on how to manage their business. This is especially true for diversified portfolios, such as index funds or actively managed funds whose performance is benchmarked relative to a diversified index. Rather, engagement provides asset managers with an opportunity to improve their understanding of portfolio companies and their governance structures to better inform proxy voting decisions. Notably, shareholders are not given the opportunity to vote on competitive strategy, nor is there evidence that directors run on a “platform” that promises to promote a competitive strategy. Furthermore, engagement by asset managers who disclose their >5% holdings on Schedule 13G is limited in both content and context by SEC regulations, the breech of which could lead to civil and criminal penalties.

Finally, the allegation that index managers’ failure to support activist campaigns dampens competition is false. Voting against, or declining to support, an activist campaign is a reflection of the fact that there are differing, yet equally legitimate, views on how to best position a company for long-term economic success. Experience belies the allegation that index managers hinder activist campaigns. Each of the major index managers has an established track record of voting to support activist investors in proxy fights on a case-by-case basis when in their judgement such a vote is in the long-term interests of its investors.

Part IV: Policy Measures Proposed by “Common Ownership” Proponents

A number of proponents of the AST Paper’s conclusions have advanced the argument that lawmakers and policymakers must take action to curb the alleged effects of “common ownership.” The proponents of these proposals recklessly accept as true the hypothetical harm that “common ownership” has been purported to cause, but advance an agenda that would inflict concrete, immediate and wide-ranging harm upon retirees, small investors, and the economy. Implementing the proposed policy measures could impair asset managers’ ability to offer the low-cost investment solutions that millions of investors—including pension funds, government institutions and individual retirees—depend on to meet their financial goals. For regulators to adopt policy changes that would have immediate and concrete impact on investors in response to an unproven and disputed hypothesis is unwarranted. Below we discuss two of the most problematic policy proposals that have been suggested.

A. Limiting mutual funds to one company per industry

One set of commentators has suggested a complicated, multi-step process in which, each calendar year, the FTC would disseminate a list of concentrated industries, solicit comments on this list, and then publish a final list within a specified time period. Following this pronouncement, asset managers would have a choice to invest in only one issuer per each concentrated industry, or hold less than 1% of each issuer in that concentrated industry. With no empirical support, these authors claim that any investment losses due to lack of diversification from only owning one company per industry would be minimal. And in any event, those investors looking to “squeeze out those last percentage points of diversification” can simply buy a multitude of different index funds across fund providers.

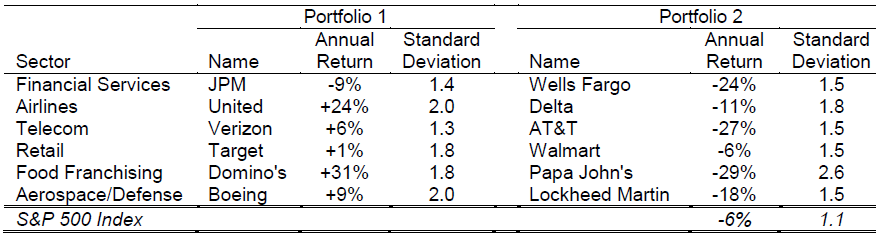

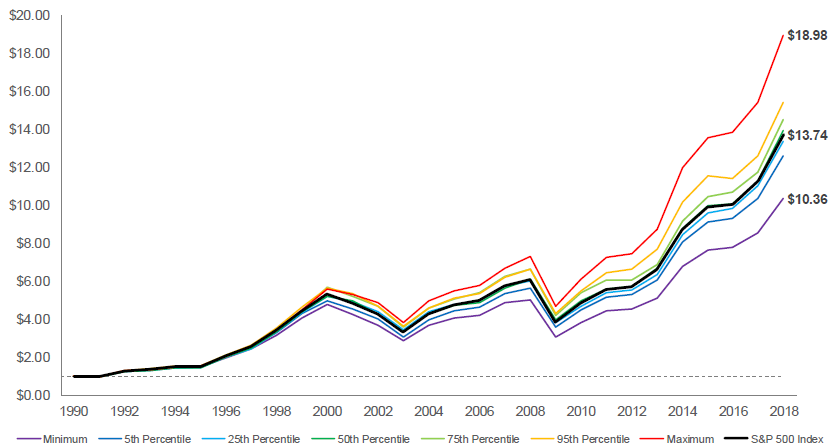

We cannot overstate how many incorrect assumptions about investing, capital market operation, and investor behavior are incorporated in this proposal. Idiosyncratic risk of a single company is a well-understood concept in portfolio construction and underlies much of the academic work leading to diversification of risk. Exhibit 8 below illustrates the risk of investing in only one company per sector, comparing one investors’ portfolio with shares in companies among the better performers in their industry, and another with shares in companies among the worst performers.

Exhibit 8: Idiosyncratic Risk of Non-Diversification

2018

Note: Performance is calculated as the annual return. The standard deviation is calculated using daily returns. Source: Bloomberg.

Owning only one company per “concentrated industry” would have a dramatic effect on the performance of index funds. To illustrate, we asked Analysis Group to perform a Monte Carlo simulation analysis of a counterfactual world in which mutual funds investing in S&P 500 Index component stocks over the period 1990 to 2017 operated within a stylized version of the proposed policy.

Exhibit 9 shows the simulated cumulative value of a $1 investment in the counterfactual funds under the proposed ownership limits, with selected percentiles over the period 1990 to 2017.

Exhibit 9: Cumulative Value of $1 Investment

S&P 500 Index vs. 1 Million Monte Carlo Simulations

1990–2017

Note: Returns are adjusted for stock splits, buybacks and reinvested dividends.

Source: Morningstar Direct; CRSP.

Ex post, the cumulative value of a $1 investment in a traditional S&P 500 Index fund over the period 1990 to 2017 would have been $13.74. However, according to the Monte Carlo simulation analysis, the cumulative value of a $1 investment in the counterfactual, policy-constrained, funds over the same period would have varied considerably. Households would be forced to take considerably more idiosyncratic risk under this policy. Across one million simulations, the cumulative value of a $1 investment would have ranged from $10.36 to $18.98. Excluding outliers, the 95th percentile outcome ($15.42) would have been 22% higher than the 5th percentile outcome ($12.61).

The results of Analysis Group’s work suggest that S&P 500 Index funds—and, indeed, institutional or individual investors trying to replicate the return of any such market index—will likely experience a wide variation in investment outcomes under such a policy. The proposed ownership limits thus needlessly expose investors to significant firm-specific risk.

But even more fundamentally, implementing these policies would substantially alter the product offerings that have made participation in the financial markets more accessible and affordable to the average investor today than it has at any other point in history. Instead of gaining cross-industry exposure through a single investment instrument, investors would be forced to choose between selecting a single component of each industry, much like an active portfolio manager, or foregoing exposure to a given industry entirely. In choosing either option, the investor would be forced to accept increased portfolio risk and potentially lower returns in the affected portfolios.

B. Restricting certain investors’ ability to vote

Another proposed policy “remedy” is to limit asset managers’ ability to vote. BlackRock believes that the right to vote at shareholder meetings is a fundamental right that attaches to share ownership, and this proposal essentially disenfranchises a group of shareholders. In the US, this proposed policy runs counter to rules and guidance that apply to asset managers promulgated by the Department of Labor and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Further, constraining asset managers’ ability to vote shares on behalf of clients who delegate this responsibility to them would disenfranchise their clients—the underlying asset owners who are most often long-term investors saving for retirement. In addition, this would materially change the balance of power between management and other shareholders. Depending on the company and the composition of its shareholder base, restricting asset managers’ ability to vote may: (i) increase the power and impact of proxy advisors, (ii) empower actors such as activist hedge funds, or (iii) entrench management. All of these outcomes would have negative implications for long-term savers whose interests are not always aligned with those of other shareholders.

These policy proposals are deeply troubling, especially as they are solutions in search of a non-existent problem. The benefits of institutional investment management, index investing and portfolio diversification are well-established, and each proposed remedy would fundamentally diminish the options available to investors.

Conclusion

The “common ownership” theory itself and the analysis presented in the AST Paper demonstrate a lack of understanding of the asset management industry, including index inclusion rules, the role of proxy advisors, and the incentives of asset managers. A growing body of literature calls into question the AST Paper’s methodologies and conclusions. In addition, the sensitivity testing performed by Analysis Group demonstrates that correcting the incorrect treatment of either control rights during bankruptcy or financial incentives of asset managers eliminates the statistical significance of the results presented in the AST Paper. Based on these methodological problems as well as the conceptual flaws in the common ownership theory itself, BlackRock believes that the findings in the AST Paper are invalid, and at the very least should not be used as the basis for public policy efforts.

Furthermore, the policy proposals that have been suggested by proponents of the “common ownership” theory would do tremendous harm to American savers and retirees, and our nation’s capital markets. Such changes would increase costs and portfolio risk for everyday investors, and substantially reduce the well-known benefits that low-cost diversified index investing provides to asset owners. In addition, many companies that currently benefit from their stock’s inclusion in indexes may find it more difficult to attract capital to invest and grow their business. Finally, engagement by institutional investors plays an important role in the corporate accountability chain and has value not just for shareholders, but for society as a whole. Unless and until the nascent “common ownership” hypothesis and the purported harm it causes can be empirically established, any policy discussions are premature and reckless.

* * *

BlackRock appreciates the opportunity to provide our input in connection with the Commission’s hearings on this important debate. If you have any questions on our comment letter, contact the undersigned.

Sincerely,

Barbara G. Novick Vice Chairman

Bennett W. Golub, PhD Chief Risk Officer

cc:

Honorable Joseph J. Simons, Chairman, Federal Trade Commission

Honorable Noah Joshua Phillips, Commissioner, Federal Trade Commission

Honorable Rohit Chopra, Commissioner, Federal Trade Commission

Honorable Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, Commissioner, Federal Trade Commission

Honorable Christine S. Wilson, Commissioner, Federal Trade Commission

Honorable Jay Clayton, Chairman, Securities and Exchange Commission

Honorable Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Commissioner, Securities and Exchange Commission

Honorable Hester M. Peirce, Commissioner, Securities and Exchange Commission

Honorable Elad L. Roisman, Commissioner, Securities and Exchange Commission

Appendix: Correcting the Record Regarding Factual Misstatements about BlackRock During Hearing #8

There were a number of false claims made by panelists during Hearing #8 regarding the extent and nature of BlackRock’s engagements with companies in which it invests on behalf of clients. We would like to correct the record in regards to these claims and ask the Commission to consider these points when reviewing the record from the hearing.

A. BlackRock does not tell companies to fire employees.

First, in his remarks and associated PowerPoint slides, Martin Schmalz made categorically false claims about the extent to which BlackRock exerts influence on the companies in which we invest on behalf of clients. At the hearing, Dr. Schmalz stated that “Larry Fink [BlackRock’s CEO] is on the record saying we can tell a company to fire 5,000 employees tomorrow.” In making this assertion, Dr. Schmalz mischaracterized the nature of engagement between BlackRock and companies in which it invests, as well as the extent to which BlackRock is able to influence strategic decisions of companies. This particular quote appeared in a University of Chicago blog post about a discussion at the 2016 World Economic Forum. An exact transcript of that event is not available to our knowledge. However, we believe that the quote referenced was taken out of context. During the panel, which was a discussion of corporate governance and sustainability topics, Fink referenced a hypothetical counterfactual where investors are focused solely on short-term profit seeking rather than longer-term drivers of company performance. BlackRock’s investment stewardship activities do not entail telling companies to fire or hire employees.

B. BlackRock has not lobbied for mergers of European banks.

In his remarks, Dr. Schmalz quoted a headline from German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine, which he translates as, “Fund giant BlackRock lobbies for mergers of European banks.” The article drew on an interview on the topic of challenges and disappointing returns in the European banking market. The interviewer’s suggestion of a merger between two German banks, Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, is dismissed, with the comment that “If we’re talking about a need for consolidation, then we should not do that at the national level”.

Dr. Schmalz’s quotation of the article title appears to be intended to demonstrate a “mechanism to affect mergers”, and therefore competitive outcomes. However, the article itself contains neither proactive statements by BlackRock in favor of mergers among European banks, nor specific comments regarding Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, or any other merger scenarios. It is our view that headlines of newspaper articles should not be relied upon as statements of fact.

C. BlackRock does not dictate to companies their share buyback strategies.

Additionally, in his remarks Dr. Schmalz cites that “BlackRock’s CEO L. Fink directly expresses his views on payouts and capex in letters to CEOs, threatens votes against management” as evidence that common ownership affects corporate financial choices.1 This is a misleading assertion regarding BlackRock’s engagement with companies in which we invest on behalf of our clients.

As a fiduciary, BlackRock maintains a dedicated investment stewardship team that aims to understand companies’ business models and ask probing questions—not to tell companies what to do. BlackRock’s Investment Stewardship team engages with companies to encourage practices that drive sustainable, long term growth.

These engagements may touch on topics including share buybacks and capital expenditures as they relate to long-term strategy. However, the suggestion that Mr. Fink’s annual letter to CEOs constitutes a command to companies as to their specific strategies regarding share buybacks is clearly false. We do not dictate to companies how they should run their corporate balance sheets, nor do we have the ability to do so.

* * *

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century

More from: Barbara Novick, Bennett Golub, BlackRock

Barbara Novick is Vice Chairman and Bennett Golub is Chief Risk Officer at BlackRock, Inc. This post is based on BlackRock’s letter to the FTC challenging the theory of common ownership.

BlackRock, Inc. (“BlackRock”) appreciates the opportunity to comment in connection with the eighth session of the Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC” or the “Commission”) hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century. We welcome the FTC’s Hearings Initiative and efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of competition and consumer protection law, enforcement priorities, and public policy matters in the context of America’s diverse and evolving economy. As an asset manager that invests in thousands of American companies on behalf of our clients, our business benefits from competitive markets and industries. We commend the Commission for prioritizing information gathering and fact-finding to inform its policy efforts.

BlackRock’s comment letter addresses the topics discussed in Hearing #8, “Common Ownership”. Specifically, this letter focuses on the following items from the Hearing Notice: (i) item one, which requests comments on the state of the econometric and qualitative evidence for and against the underlying “common ownership” theories, (ii) item four, which requests comments on potential mechanisms by which concentrated holdings may lead to anticompetitive harm, (iii) item five, which requests comment on institutional investors’ incentive and opportunity to affect corporate governance, and (iv) item six, which requests comment on enforcement and policy responses. We welcome the Commission’s decision to solicit industry views on these important regulatory and policy topics.

Introduction

A nascent academic literature purports to link institutional investors’ positions in more than one firm in a concentrated industry to decreased competition and higher consumer costs. This theory, widely referred to as “common ownership”, has received attention largely based on a single academic paper that purports to demonstrate, on average, a 3-5% increase in the cost of a US domestic airline ticket as a result of “common ownership” (the “AST Paper”). The authors of this paper (“AST”) posit that firms in a single concentrated industry whose shares are owned, in part, by common minority investors maximize industry profits over firm profits, or, at least, that the managers of the competing firms assume this would be their shareholders’ preference and accede to it.

AST have extrapolated their theory about airline ticket prices to argue that “common ownership” effects are present across the economy, stunting competition in a number of different industries and leading to a social cost that accompanies the private benefits of diversification and good corporate governance. The authors ascribe responsibility for this purported effect to asset managers including BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street.

Many academics have voiced deep skepticism about the theory of “common ownership”, which suffers from serious conceptual flaws including a lack of a plausible causal mechanism, incorrect assumptions about control by non-controlling shareholders, and a failure to distinguish the incentives of asset owners from asset managers. In particular, these academics argue that the model applied by AST, which was designed to analyze partial acquisitions of competitors and joint ventures, is not an appropriate model for studying “common ownership”. This is because unlike cross-ownership, “common ownership” involves minority equity ownership interests of thousands of corporate, institutional, and individual investors. Since these investors have varied incentive and governance structures, AST’s uniform assumptions concerning investors’ financial interests and corporate control fail to account for practical and legal realities.

By contrast, other commentators assume the AST Paper’s conclusions are sound, and have proposed remedies to address the supposed problem, including limiting asset managers to one equity position per industry, putting hard limits on managers’ holdings, or prohibiting managers from voting shares. By increasing the cost and risk of diversified investment products, such proposals would undermine households’ access to low-cost diversified investments. Moreover, given the lack of support in the academic literature for the AST findings themselves, the vast majority of studies and most of the panelists who presented at Hearing #8 have concluded that any discussion of policy interventions is extremely premature and not justified by the state of empirical research, which is grounded on highly controversial findings and theoretical research.

The proposed remedies seek to fix a problem that does not exist, and we believe these proposals themselves should be cause for concern. 100 million Americans, or 45% of all US households, own mutual funds; 56% of these households’ mutual fund assets are held in retirement accounts. Implementing the remedies proposed by “common ownership” proponents would constrain the availability of reasonably priced diversified investment products that millions of investors—including pension funds, government institutions and individual retirees—depend on to meet their financial goals. In addition, remedies that involve limiting diversified funds to one company per sector would lead to billions of dollars of divestment from public companies by mutual funds, creating massive flows and generating substantial transaction costs. In accepting as true the hypothetical, marginal harm that the AST Paper has purported to identify, proponents of these extreme remedies recklessly advance an agenda that would have concrete and wide-ranging harm on everyday investors and the economy as a whole.

BlackRock believes that any debate on “common ownership” should be evidence-based and grounded in accurate and robust analysis demonstrating anti-competitive effects, as well as subject to rigorous cost-benefit analysis. To date, the existing research on this topic does not meet this standard.

The remainder of this letter is organized in four parts:

Part I: Describes findings from the replication of results presented in the AST Paper and testing of those results for sensitivities to flawed assumptions. This testing was performed by a third party consultant, Analysis Group, hired by BlackRock. Analysis Group’s findings indicate that the AST Paper’s results do not hold up when incorrect assumptions are corrected.

Part II: Explains index inclusion rules and the implications for treatment of companies during periods of bankruptcy in the AST Paper. Airline company stocks were dropped from the indexes during bankruptcy which is an important methodological flaw in the AST Paper.

Part III: Describes some additional flaws with the AST Paper.

Part IV: Addresses policy measures that have been proposed by “common ownership” proponents.

In addition, we have included an Appendix that corrects the record on factual misstatements about BlackRock made by commentators during the Hearing #8 presentations.

BlackRock has chosen to voluntarily make available the code Analysis Group used to perform the analyses in Part I of this letter. This code builds off the materials released by AST after the publication of their paper in the Journal of Finance in August 2018. A replication package can be downloaded at https://www.blackrock.com/common-ownership. It is BlackRock’s hope that making the code used by Analysis Group publicly available will help ensure the theoretical, policy and legal discussions on this topic are held to the highest academic standards. We invite a full review of the analysis.

Part I: Testing the AST Paper’s results

Notwithstanding the theoretical flaws that have been previously identified by BlackRock and a range of academics, which we believe call into question the theory of “common ownership” itself, AST have recently released to the public information that has permitted BlackRock to engage a third party consultant, Analysis Group, to replicate AST’s results. Analysis Group was able to replicate AST’s results and to test the sensitivities of these results to various methodological choices, or assumptions, made by AST. Analysis Group’s sensitivity analysis reveals that AST’s results are highly sensitive to incorrect assumptions regarding corporate control and financial incentives. We believe Analysis Group’s findings suggest that even the statistical results based on AST’s own model and data are not robust to plausible alternative assumptions.

Specifically, Analysis Group found that correcting for either of the following critical flaws in AST’s assumptions eliminates the statistical significance of AST’s findings regarding anti-competitive effects of “common ownership” :

When the aforementioned erroneous assumptions are corrected, Analysis Group finds no statistically significant relationship between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices. We believe these findings suggest that the results presented in the AST Paper are not robust to even small changes in assumptions. At the very least, the AST paper should not be used as the basis for formulating policy decisions by the FTC or any other agency given the unreliability of the findings. A memo with information that can be used to replicate Analysis Group’s results used in forming these conclusions is publicly available at https://www.blackrock.com/common-ownership.

A. Background on AST Paper Methodology

Drawing on economic research evaluating “cross-ownership” between firms (e.g., a joint venture between competing firms), AST use an economic measure that augments standard measures of industry concentration to account for the effects of “common ownership”. AST claim that this measure, referred to as “MHHI Delta”, accurately captures the impact of “common ownership” on competition.

As used by AST, MHHI Delta reflects two components of an investor’s ownership in competing firms. The first is the investor’s right to vote in corporate decisions in the firm, which captures its extent of “corporate control”. The second is the investor’s rights to a share in the profits of the firm, which captures its “financial incentives” AST assume that both of these terms are directly proportional to the fraction of total shares held by each investor for each quarter of the period they study. Furthermore, they do not account for any relevant effects that bankruptcies can have on investors’ ownership and control rights. The following two subsections will show that these two incorrect assumptions drive the statistical significance of AST’s results, and when they are corrected, the AST Paper’s results are no longer statistically significant.

B. Testing Sensitivity of “Control” Assumption During Bankruptcies

The AST Paper purports to analyze corporate control of airlines using a measurement period when three of the four major airlines—AMR Corp. (“American Airlines”) (2011-2013), Delta Air Lines, Inc. (“Delta Air Lines” (2005-2007), and UAL Corp. (“United Airlines” (2002-2006)—experienced extended bankruptcies. Other major airlines and smaller airlines also experienced shorter bankruptcies during this period. Exhibit 1 shows that during 28 of the 56 quarters (or 50%) covered by the AST Paper’s sample, at least one major US airline was in bankruptcy.

Exhibit 1: Dates of Bankruptcies of Major Airlines in the US

Note: Number of quarters do not sum to total because of overlap between quarters.

Source: AST data production.

Despite this important characteristic of the measurement period and sample analyzed, the AST Paper utilizes simplifying assumptions that AST acknowledge are not in line with reality. Specifically, the AST Paper assumes that shareholder control and financial incentives are unchanged when an airline enters bankruptcy, and remain constant at pre-bankruptcy levels throughout the entire course of the bankruptcy. As we will discuss in Part II, this assumption is particularly incorrect for index fund managers because bankrupt companies are removed from equity indexes, causing index funds to sell their shares at or shortly after the bankruptcy filing date. In other words, the AST Paper assumes index fund managers had “control” over the bankrupt companies when, in fact, they did not even own shares in those companies at the time of bankruptcy.

Putting this fundamental issue aside for the moment, assuming equity holders have “control” of a company that is in bankruptcy defies legal and practical realities. When a firm files for bankruptcy protection under US law, the company’s executive managers are under an obligation to act first in the best interest of the firm’s creditors and not of equity holders. Equity holders are “last in line” to receive cash flows from the bankrupt firm, and thus any influence equity holders may have had over management pre-bankruptcy is substantially reduced or eliminated during bankruptcy. The rights of secured and unsecured creditors are prioritized over equity holders by law, and equity holders typically only receive compensation or regain their rights to cash flows once all creditors have been adequately compensated. Pre-bankruptcy shareholders typically have no voting rights once a firm enters bankruptcy protection. Importantly, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines and United Airlines did not hold a single shareholder meeting during the period they were in bankruptcy protection, giving their equity holders no formal venue to even attempt to exert influence.

AST appear to recognize their flawed assumption, as they note that “[b]ankruptcies may confound the results because shareholders have no de jure control rights during such times, and this feature is not captured in our computation of MHHI delta.” In fact, contrary to AST’s simplifying assumption that control continues throughout the bankruptcy period, the impact of bankruptcies on corporate control during the 28 quarters when airlines were in bankruptcy can easily be incorporated into the analysis by setting shareholder control rights during these periods to zero. Doing so reflects AST’s own intellectual concession that equity holders have no de jure control rights during bankruptcy.

AST claim to have controlled for this incorrect assumption regarding bankruptcy by running placebo and robustness checks. While AST conclude that their “results are generally weaker in markets and at times affected by bankruptcies,” we believe the checks they conducted were insufficient to validate their main results. AST thus fail to incorporate the actual control rights present during bankruptcy periods.

To test the sensitivity of the AST Paper’s results to this assumption, Analysis Group incorporated this adjustment into the AST methodology. After adjusting for the lack of equity holder control during bankruptcy, the association between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices across the entire study period of the AST Paper is not statistically different from zero. Exhibit 2 illustrates the weakness of the results when control rights are treated correctly. The ranges described by the bars in this exhibit represent the 95% confidence interval around the respective estimates. While the midpoint (i.e., the point estimate) of the right-most bar is positive, the confidence interval includes zero, which means that the estimate is statistically indistinguishable from zero, invalidating AST’s conclusions.

Exhibit 2: Estimated Range of the Effect of “Common Ownership” on a $300 Airfare

Range reflects a 95% Confidence Interval

Note: Results from market-carrier level regressions.

This critique of the AST Paper has been raised before in an academic paper that called into question AST’s results. However, AST dismissed these criticisms largely on the basis that those academics were unable to fully replicate the AST Paper’s baseline results without access to the original code and data. The same cannot be said of the analysis presented in this letter, which is based on the actual code and data from the AST replication package. As the AST Paper’s purported correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices loses statistical significance once this rudimentary correction for bankruptcy periods is made, this analysis demonstrates that the AST Paper’s results are not robust.

C. Testing Sensitivity of Assumption of Equivalent Economic Interests of All Institutional Investors Given Differences between Asset Managers and Asset Owners

While the interests of asset owners and asset managers are generally aligned, the AST Paper incorrectly accounts for the different financial incentives that different types of institutional investors have. Specifically, the AST Paper incorrectly assumes that asset owners and asset managers have identical financial incentives. The authors’ reliance on regulatory reporting data ascribes a financial interest that is directly proportional to the amount of shares reported, regardless of whether the reporting entity is an asset manager or asset owner. In reality, asset managers have substantially less financial interest in the portfolio companies held by funds they manage than the shareholders of those funds. While asset owners are the direct beneficiaries of the gains and losses generated by shares they own, asset managers are paid a management fee—as small as a few hundredths of a percent—based on the aggregate value of assets under their investment discretion. Thus, asset owners’ financial interest reflects the full change in market value of their shares in the company, while asset managers’ direct financial interest is necessarily limited to the management fees they earn. By ignoring differences among different types of shareholders’ financial incentives, the AST Paper overestimates “common ownership” concentration.

To illustrate this point, consider a $1 million investment in a publicly-traded company’s stock. If this position were held in an index fund managed by an asset manager that charges a 5 basis point management fee (i.e., 0.05%), an increase in the company’s share price of 1% would provide the advisor with $5 in additional fees. By contrast, an individual asset owner holding the position directly would realize a $10,000 gain on their investment. The asset owner’s financial incentive in this example is 2,000 times larger than the asset manager’s incentive.

As an aside, this example assumes that the 1% share price increase of an individual equity position has a proportionate positive impact on an investor’s overall portfolio value. However, depending on the source of incremental profit, this is not always the case. Consider the effects of an increase in airline ticket prices alleged by AST: a broad based index fund that holds securities of companies in a diverse array of industries, airlines being only one of many, may experience a net negative impact from an increase in airline ticket prices because higher airline ticket prices increase the travel expenses incurred by other companies in the portfolio. As Exhibit 3 demonstrates, airlines represent less than 1% of the most frequently used equity indexes.

Exhibit 3: Weighting of Airlines in Equity Indexes

Source: Index weightings from S&P, MSCI, FTSE, Russell, retrieved from BlackRock Internal Data Systems, November 2017.

Because they are compensated by management fees, asset managers’ greatest financial incentive is to compete with other asset managers on the basis of relative investment performance (net of fees) and client service. Index fund managers demonstrate relative performance by most closely tracking the index. Since index funds hold more or less identical portfolios of companies, encouraging an increase in the price of one company or sector has little effect on relative performance. Indeed, even actively managed funds must be “overweight” a stock or a group of stocks compared to competing funds for their relative performance to benefit from higher equity returns of a given company or sector. As such, encouraging an increase in prices of a single company or sector has very limited benefit to asset managers of diversified portfolios relative to their primary commercial interests.

The incorrect assumption that asset owners and asset managers have identical financial incentives impacts a large portion of the ownership data included in the AST Paper’s analysis, as 75-85% of shares during any given quarter of AST’s analysis are managed by traditional investment managers of diversified portfolios (such as BlackRock, Capital Group, Fidelity, State Street Global Investors, T.Rowe Price, and Vanguard), as shown in Exhibit 4 below.

Exhibit 4: Scaled Percentage of Total Shares by Investor Type

American Airlines

2001–2014 quarterly data

Notes:

[1] Following AST, data on shareholdings are sourced from Thomson Reuters Spectrum, AST’s manually collected SEC Form 13F filings, and AST’s manually collected proxy statements. Further, share counts are aggregated across separate entities. (See AST, p. 16, fn. 10).

[2] The data does not include owners with equity holdings smaller than 0.5%.

[3] Ownership type is defined by S&P Capital IQ. Asset owners include government pension sponsor, family offices/trust, bank/investment bank, charitable foundations, individuals/insiders, non-institutional, and unclassified investors.

Sources: AST Replication Package; Thomson Reuters Spectrum.

In order to test whether AST’s overstatement of the financial incentives of traditional asset managers affects the results presented in the AST Paper, Analysis Group replicated the AST Paper’s regressions (again, using the AST Paper’s data and code) but instead of assuming equivalent economic interests for all institutional investors, Analysis Group adjusted asset managers’ financial incentive to be 1% of their ownership share. 1% is meant to reflect a more realistic estimate of the economic interest in the company that an asset manager would have due to its investment management fee. 1% is a conservative overestimate given that investment management fees on US equity investment products are typically much lower than 1%. For example, expense ratios of three US Large Capitalization Stock ETFs offered by three different providers are between 0.03% and 0.0945%. For actively managed products, Reuters recently reported that the asset-weighted average expense ratio of actively managed equity mutual funds fell from 1.08% of assets managed in 2001 to 0.86% in 2014. Management fees are only a subset of a mutual fund’s total expense ratio. During the AST Paper’s period of study, management fees for mutual funds were typically no greater—and often much less—than 1%.

The same article shows the asset-weighted average expense ratio of passively managed (index) equity mutual funds fell from 0.25% in 2001 to 0.11% in 2014.

After adjusting for asset managers’ financial incentives, Analysis Group found that the correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices is not statistically different from zero, as is illustrated in Exhibit 5 below. As such, the AST Paper’s test of the correlation between “common ownership” and airline ticket prices is not robust to this minor correction.

Exhibit 5: Estimated Range of the Effect of “Common Ownership” on a $300 Airfare

Range reflects a 95% Confidence Interval

Note: Results from market-carrier level regressions.

Part II: Index Inclusion Rules and the Treatment of Companies during Periods of Bankruptcy

As noted in Part I assuming that index fund managers had “control” over airlines when they were in bankruptcy is incorrect. In their paper, AST assume that asset managers’ equity holdings in airlines remain constant for the duration each airline is in bankruptcy and “repeat the last observed value for percentage of shares owned” in bankrupt airlines.

This assumption is grossly inaccurate at least in the case of index fund managers (and likely for a portion of active managers as well) and reflects a lack of understanding of index construction rules. Index providers such as S&P Dow Jones and Russell Investments remove companies in bankruptcy protection from their indexes concurrent with or before the bankruptcy filing date and the de-listing of the issuer’s equity from a stock exchange. Given their objective is to track the index, index funds sell their shares in bankrupt companies at or shortly after the bankruptcy filing date. Exhibit 6(a) shows that all major airlines in the US were removed from S&P indexes during their respective bankruptcies. Exhibit 6(b) shows that airlines were added back to S&P indexes after they emerged from bankruptcy, only when they could meet the criteria for reinstatement.

Exhibit 6(a)—Bankruptcy Filings of Major Airlines and Deletion from S&P Indexes

Source: SEC filings and S&P announcements.

Exhibit 6(b)—Bankruptcy Exits of Major Airlines and Reinstatement to S&P Indexes

Source: SEC filings and S&P announcements.

For example, the overwhelming majority of holdings in portfolios managed by BlackRock in the major US airlines prior to their respective bankruptcy filings were held in index funds. BlackRock therefore sold nearly all of its holdings upon each airline’s bankruptcy filing, and did not repurchase shares until each airline had been reinstated to the relevant index. This reality of index management leads to significant differences between the shareholdings attributed to BlackRock in the AST Paper and the amount of shares actually held by BlackRock-managed portfolios during the AST Paper’s study period.

Exhibit 7 provides an example of the size of this discrepancy during the period when American Airlines was in bankruptcy.

Exhibit 7: BlackRock Equity Holdings

American Airlines

2011Q3–2014Q1

Notes:

[1] The “AST” line is sourced from Thomson Reuters Spectrum and AST’s manually collected SEC Form 13F filings. Share counts are aggregated across separate BlackRock entities. Shares from 2011Q3 are “forward-filled” for the bankruptcy period.

[2] The “Actual BlackRock Portfolio Holdings” line for 2011Q–2013Q4 is sourced from BlackRock’s internal data systems and includes shares in American Airlines that would be reported in SEC Form 13F by any of BlackRock’s entities. For quarters outside of the bankruptcy period, the values of the “Actual BlackRock Portfolio Holdings” line are the same as the “AST” line.

Source: AST Replication Package; Thomson Reuters Spectrum; BlackRock Internal Data Systems.

Part III: Additional Theoretical Flaws with AST Paper

The fundamental shortcomings specified in Part I are premised on acceptance of the AST Paper’s data and methodologies. However, in the course of replicating the AST Paper’s results, Analysis Group identified several other data and methodological issues with the AST Paper. While a comprehensive investigation of each of these issues is beyond the scope of this letter, future empirical research should evaluate the impact of correcting for the flaws described below.

A. Flawed Reliance on Threshold Reporting Data

The AST Paper measures “common ownership” using Form 13F disclosures filed by asset managers. Form 13F is a quarterly SEC filing in which institutional investors with investment discretion over $100 million in exchange-traded equity securities provide a snapshot of their holdings. While Form 13F data is intended to provide a degree of visibility into institutional investor holdings, it provides an incomplete picture of investors’ total economic exposure and voting rights, and does not provide a complete picture of a company’s shareholder base.

Institutional investors interpret the SEC’s Form 13F instructions and guidance differently, leading to inconsistencies in how holdings are reported. For example, some large asset managers who have a robust internal proxy voting function interpret the 13F rules as requiring them to report having no voting authority over such shares. This is a critical point, as the AST Paper claims to only count as “control shares” those positions over which an asset owner or manager reports having “sole” or “shared” voting authority on its 13F reports. The AST Paper does not appear to correct for inconsistencies in how different asset managers report holdings on Form 13F.