Subodh Mishra is Executive Director at Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. This post is based on an ISS paper by Kosmas Papadopoulos, Managing Editor and Executive Director with ISS Analytics, the data intelligence arm of Institutional Shareholder Services. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Elusive Quest for Global Governance Standards by Lucian Bebchuk and Assaf Hamdani.

Analyzing corporate governance at companies in emerging markets can be really tough. A combination of differing regulatory standards, disclosure requirements, market norms, local investor preferences, and more all collude to make the evaluation of governance structures difficult. Giving credit where due, emerging market economies have made significant corporate governance strides over the past decade, as the adoptions and revisions of governance codes and relevant regulations have led to better disclosure standards, higher levels of board independence, and more shareholder protections.

Despite these developments, emerging markets continue to have a unique set of characteristics which require special attention when assessing corporate governance at the country level and at the company level. At the country level, the legal framework, the strength of institutions, and the rule of law all affect the quality of governance of individual firms. And at the company level, ownership structures will often determine the types of governance challenges a company may face, as concentrated ownership may lead to potential risks of management entrenchment or the risk of expropriation of minority shareholders.

In this environment, mindful investors both strive and struggle to monitor governance, environmental, and social issues as well as the quality of financial performance. In this article, we review some of the most important factors for consideration when assessing corporate governance in emerging markets.

County-level analysis of governance risks

The old adage “where you stand depends on where you sit” applies in spades to emerging market corporate governance. The quality of governance of a country’s public institutions will invariably affect the quality of corporate governance of firms incorporated in that jurisdiction. Corruption, bureaucracy, lack of transparency, and the level of adherence to the rule of law at the home jurisdiction may impact a company’s own governance practices while also exposing it to significant risks. An evaluation of public governance at the country level may help set expectations of the types of risks associated with investing in individual companies. Indices developed by international organizations, such as the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators or Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index may serve as helpful pointers.

Shareholders should also develop a good understanding of the legal framework related to the rights of shareholders and the protection of minority shareholders. Capital markets are still rapidly developing in many emerging markets, and a shareholder culture may not be fully developed or embedded in the legal system. The World Bank, as part of its Doing Business Report, has developed a Protecting Minority Investors score, which, among other factors, assesses the ability of shareholders to bring suit, director’s liability, and transparency towards minority investors. Political risk may also be a factor, as political decisions could, in some cases, threaten relatively fragile institutions.

In the context of these macro factors, corporate governance rules and regulations offer some important measures that improve the level of confidence in capital markets. Codes, listing rules, and legislation provide mandates relating to board practices, shareholder rights, disclosures, voting mechanics, and environmental and social risks. While corporate governance codes generally apply on a comply-or-explain basis, they have been proven effective in moving markets forward towards better governance practices. On the regulatory front, most emerging market economies continue to show progress, as they have not only adopted corporate governance codes and regulations to establish their standards, but they conduct periodic revisions to further advance these standards. As the table below illustrates, most major emerging market economies have updated their codes in the past three years. This recent activity shows that corporate governance has become a policy priority for many of these countries.

List of Corporate Governance Codes in Select Emerging Markets

| Country | Last Updated | Name of Code and Link to Document |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 2016 | Brazilian Corporate Governance Code (Código Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa) |

| Chile | 2012 | General Norm 341 (La Norma de Carácter General (NCG) N° 341) |

| China | 2018 | Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies in China (in Chinese) |

| India | 2018 | Report of the Committee on Corporate Governance |

| Indonesia | 2006 | Indonesia’s Code of Good Corporate Governance |

| Malaysia | 2017 | Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance |

| Mexico | 2010 | Code of Corporate Best Practices (Codigo de Mejores Practicas Corporativas) |

| Philippines | 2016 | Corporate Guidelines for Companies Listed on the PSE |

| Russia | 2014 | Russian Corporate Governance Code |

| Saudi Arabia | 2018 | Corporate Governance Regulations |

| South Africa | 2016 | King IV Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa 2016 (known as ‘King IV’) |

| South Korea | 2016 | Code of Best Practices for Corporate Governance The most recent code is available in Korean. |

| Taiwan | 2016 | Corporate Governance Best-Practice Principles for TWSE/GTSM Listed Companies |

| Thailand | 2017 | Corporate Governance Code |

| Turkey | 2014 | Corporate Governance Principles—Capital Markets Board of Turkey |

Ownership structures

Ownership structures in emerging markets are characterized by concentrated ownership that can have a profound effect on the types of governance risks investors may face. The three most prevalent ownership structures are family ownership, business groups, and state ownership.

- Family ownership typically involves significant presence of members of the founding family on the board and participation in the management of the company. While the alignment of management and control may potentially reduce the principal-agent problem, this structure may lead to other conflicts, especially when it comes to plans for succession. The presence of family members on the board can potentially entrench management given the limited oversight by outsiders. Moreover, a potential rift within the family could lead to very contentious battles for control that can be distracting to the business. More importantly, succession based on family ties, instead of relying on professional management, may undermine the quality of decision making, leading to further entrenchment and eventually poor performance.

- Business groups are affiliated companies with complex ownership structures, including pyramidal ownership structures or cross-shareholding ownership. These types of entities may be part of family-owned businesses or business conglomerates without a dominant family. The main risks arising from such ownership structures pertain to related-party transactions and the risk of expropriation of minority shareholders. Some examples of such risks include overpaying for inputs or asset purchases or undercharging for outputs or asset sales, providing loans to affiliated entities, or granting excessive executive compensation.

- State control is very common in many emerging markets, where the state continues to play a major role in public services and infrastructure, including utilities, banking, and telecommunications. The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises warn against two types of risks associated with state control. On the one hand, excessive state interference can lead to lack of accountability and lack of efficiency. On the other hand, passive ownership and lack of oversight can have the same results and weaken the incentives of employees. To address these risks, sufficient checks and balances are needed to maintain professional and accountable ownership and management of the firm. Even when state-owned firms maintain rigorous corporate governance, minority investors should be aware that the goals of these firms extend beyond shareholder value, as public policy priorities may supersede economic objectives.

Company-level governance

Corporate governance at individual firms can help offset the potential governance risks that may be present due to the company’s ownership structure, local regulation, or other causes. The first and foremost mechanism for improving accountability is to provide transparency and disclosure on corporate governance. Basic disclosure requirements include timely release of financial statements, meeting agendas, and reporting on the board’s composition and oversight activities. In addition, companies should provide information on their checks and balances around conflicts of interest. Such disclosures may include approval processes with respect to related party transactions, including state-owned enterprises’ contracts with government entities, processes and procedures around the nomination of directors and the appointment of management, and succession planning for top executives. These disclosures should ensure independence in decision making, competitive market practices, and the protection of minority shareholders.

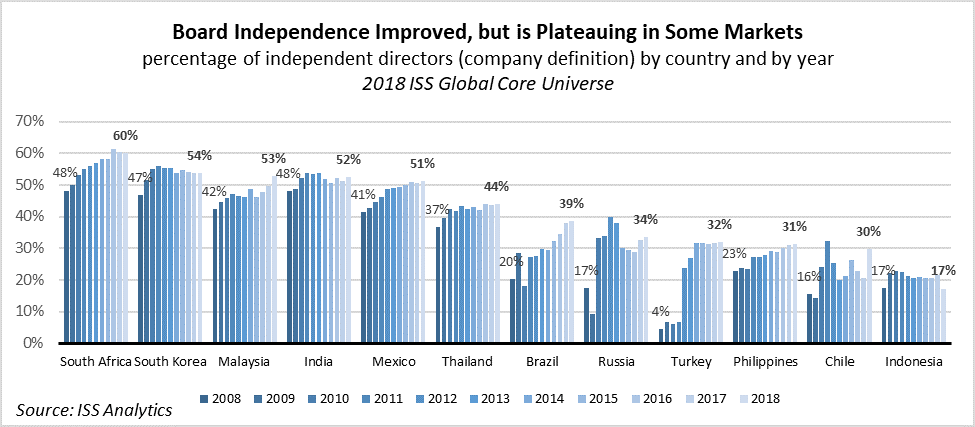

The independence of the board is another governance priority area at the company level. High levels of board and committee independence help protect against many of the risks discussed above. Moreover, providing significant oversight responsibilities to independent bodies within the board, such as key committees, may allow companies to better address conflicts. Thanks to the introduction and continued evolution of corporate governance codes, the presence of independent directors on the boards of emerging market companies has increased in the past decade. However, ISS Analytics data shows relative stagnation in many markets in the past three years.

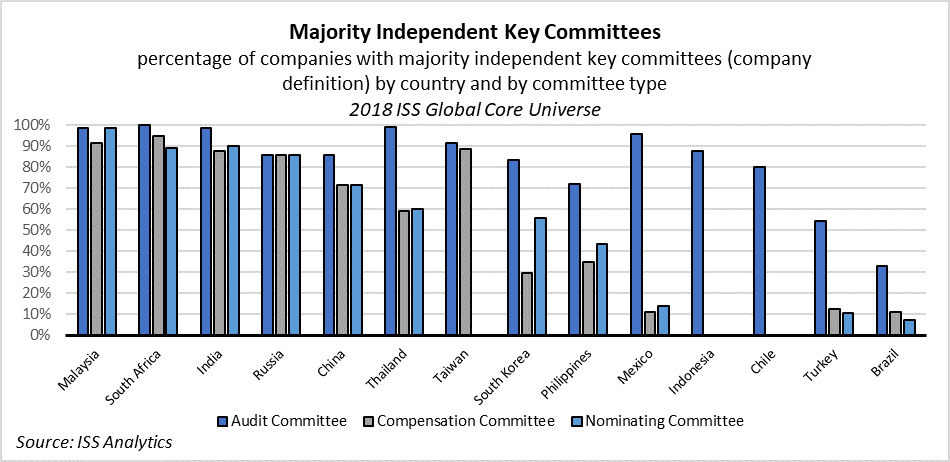

A review of key committee independence reveals that the establishment of majority independent key committees has become the standard in many markets, which is an encouraging sign given the vital function of these bodies. The role of the audit committee is of significance, given the numerous accounting irregularities observed in emerging markets in recent years. South Africa, Malaysia, and India lead the way in both board independence and committee independence.

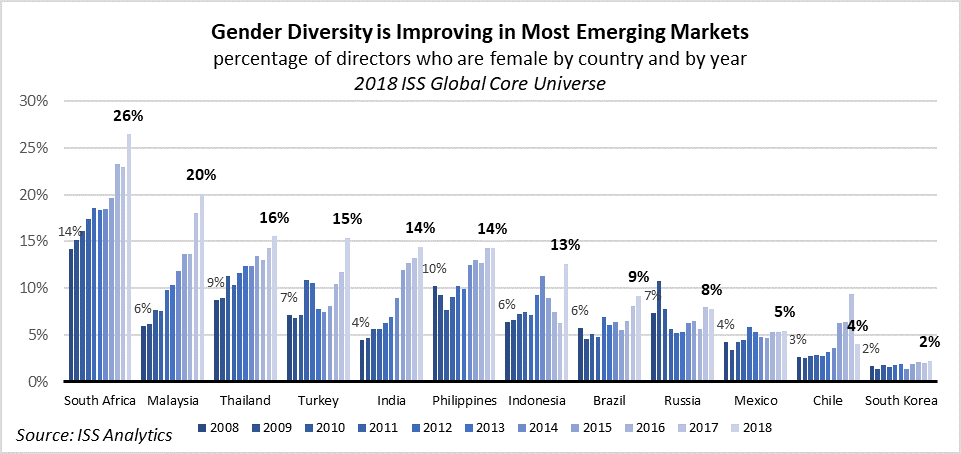

Related to board structure, board gender diversity has improved more in recent years, as we observe a noticeable increase in the percentage of female directors across most markets. In fact, India, Malaysia and Turkey are among the countries that have introduced quotas for board gender diversity through hard law (India and Malaysia) or through their codes of best practices (Turkey). In South Africa, the King IV Corporate Governance Code, effective in 2017, encouraged companies to set diversity targets, while listing rules effective the same year require a formal policy on board gender diversity. Meanwhile, the Black Economic Empowerment program incentivizes racial diversity on boards, which also encourages the inclusion and empowerment of women of color.

Environmental and Social Risks

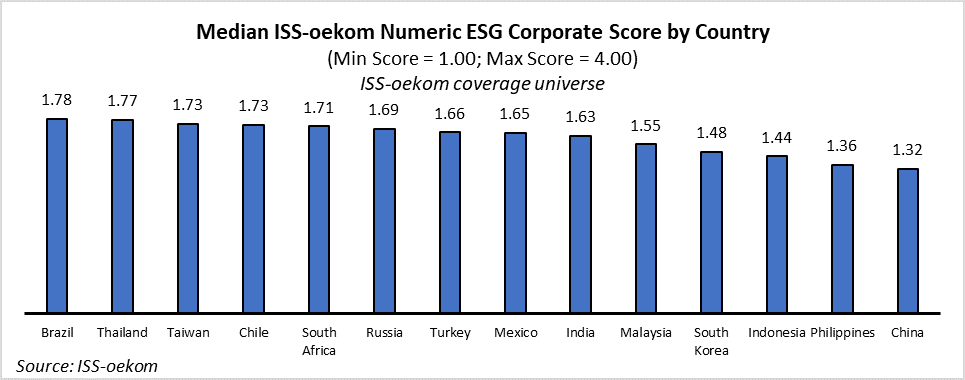

Weaker institutions, fewer regulations, and lower levels of economic development make emerging market economies more prone to environmental and social risks compared to developed markets. Health and safety, human rights, climate change, and waste and toxicity are some of the many important risks facing companies operating in emerging markets. Company disclosures on the existence of oversight mechanisms for such risks becomes especially significant. A review of ISS-oekom’s corporate ESG ratings reveals median scores ranging below the ratings of companies in developed markets. Given a maximum company score of 4.0, median company scores in emerging markets range from 1.3 to 1.8, while median company scores in developed markets range from 1.6 to 2.1. While worse performance scores on risk management of environmental and social risks by emerging market companies should not be surprising, this trend underscores the need for great investor diligence and awareness when dealing with these markets.

Monitoring the Quality of Financial Performance

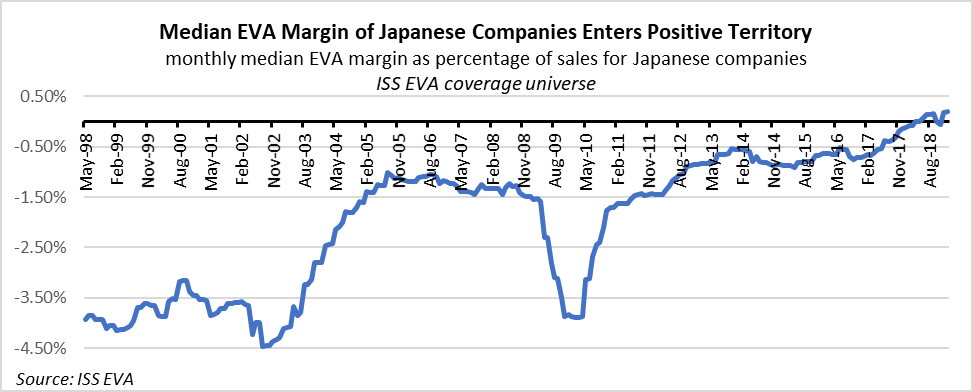

Ultimately, corporate governance aims at protecting the long-term and sustainable economic well-being of the company for the benefit of shareholders and other stakeholders. The quality of financial performance can be affected by asset allocation decisions, which can have roots in governance risks, such as related party transactions, minority shareholders expropriation, and lack of oversight of material risks. While not an emerging market, Japan is a great example of how questions about capital efficiency can be directly linked to governance. The recent update to the Japan Corporate Governance Code introduced capital efficiency as a central consideration for managers, while criticism about capital allocation often associates poor performance with entrenched boards dominated by insiders—the same types of criticisms that emerging markets companies face. The emphasis on capital efficiency in Japanese corporate governance in the past few years may be partially responsible for the upward trend we see in the market in terms of returns. Using the ISS EVA methodology of financial performance, we observe significant improvement in EVA Margin (Net Operating Profit After Tax less a charge for capital, as a percentage of sales) in the past three years, with EVA Margin turning positive for the first time during the 20 years since ISS EVA has been tracking this metric.

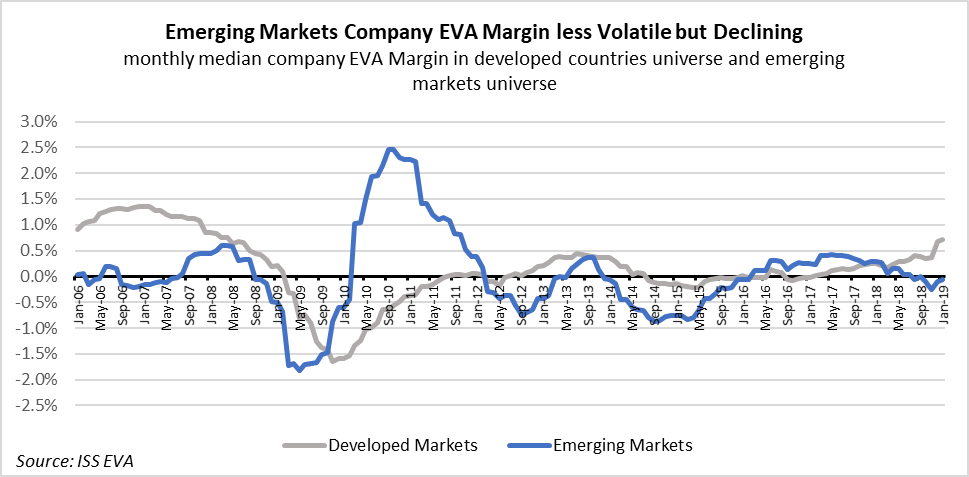

In emerging markets, we see signs of maturity in terms of financial performance, with economic profitability in the form of EVA Margin figures being less volatile during the past five years. The lower volatility is likely a result of macroeconomic trends, where evolution in corporate governance cannot be excluded as a part of the general process.

Managing governance risk in emerging markets

Despite the significant corporate governance challenges shareholders face in emerging markets, they have several tools in the repository to address potential concerns.

- Due Diligence. When becoming first acquainted with a company or a market, investors should be mindful of ownership structures and the potential risks they may pose. Identifying potential flags, such as the prevalence of related party transactions, and reviewing relevant disclosures or seeking additional information on how these risks are managed by the company may pay significant dividends in the long run.

- Monitoring. Once governance risks have been identified, continued monitoring of these factors—which may include environmental and social issues—should be become a regular part of the investment process.

- Engagement and Voting. Investors can help their investee companies manage risks by raising questions and engaging directly about issues of potential concern. Shareholders should view engagement as a long-term process, where both parties stand to gain. By addressing questions about checks and balances, succession planning, or social risks, investors may often find a partner in investee companies trying to tackle the same risks. Voting may serve as another form of engagement, whereby shareholders can voice their views about corporate governance concerns on the ballot, especially in cases where direct engagement does not lead to progress or desired outcomes.

Print

Print

One Comment

FYI: the Brazilian code mentioned in the article is issued by a private organization — it is not a law or regulation.