Hans-Christoph Hirt is head of EOS and Andy Jones is EOS sector lead of mining at Hermes Investment Management. This post is based on their Hermes memorandum.

The Hermes Shareholder Rights Directive survey was conducted to gauge levels of awareness and readiness for the amendment to the 2007 Shareholder Rights Directive coming into force in 2019. Research was conducted by Citigate Dewe Rogerson among its panel of European institutional investors, including asset owners and asset managers, during December 2018. A total of 175 responses were collected from the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain and the Nordics.

The Directive

With the aim of enhancing the stability and sustainability of EU companies, in May 2017, the European Parliament and Council agreed an amendment to the 2007 Shareholder Rights Directive (the Directive). The objectives of the Directive are to enhance transparency in the investment chain and to hold investors accountable for the integration of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions, the level and quality of long-term shareholder engagement and the alignment of investors’ investment strategy and remuneration structures with the medium-to-long term performance of their clients’ assets. All asset owners and asset managers operating in Europe will be required to comply with the national laws implementing the amended Directive.

The Directive will introduce new shareholder responsibilities, in addition to further rights, and is part of a wider push to align interests along the investment chain—companies’ boards/managers, asset managers and owners and end beneficiaries—as well as with broader stakeholders. Investors will be required to report publicly on their engagement activities and voting decisions, on a comply-or-explain basis. This is a watershed moment in the evolution of shareholder responsibility and the investment industry as a whole will need to materially step up with implications for their investment processes and resourcing to meet the Directive’s requirements.

For too long, the majority of the investment community has neglected its fiduciary responsibilities; whilst investors focused on short-term financial returns, most failed to notice the approaching global financial crisis (GFC). Alarm bells should have rung across investment houses as increasingly complex financial models, inadequately managed risk taking and inappropriate incentive structures led to poor corporate behaviour and endangered the savings of millions of pensioners.

These systematic failures were recognised by the European Commission, which in its amendment to 2007’s Shareholder Rights Directive (the Directive), highlighted that there “is clear evidence that the current level of ‘monitoring’ of investee companies and engagement by institutional investors and asset managers is often inadequate and focuses too much on short-term returns.” [1]

In the years leading up to, during and following the GFC, Hermes has consistently and vocally advocated for change and helped shape capital markets through public policy and market best practice engagement with legislators, regulators, industry bodies and other standard-setters. We have benefited from extensive experience in the implementation of a number of stewardship and governance codes globally and engaged with businesses on the importance of integrating relevant ESG opportunities and risks into their business strategies to develop sustainable business models. These actions have delivered higher industry standards and in turn, driven legislation such as the Directive.

We believe that the Directive is a profound shift for European asset managers and owners compelling all to end the short-termism that has blighted capital markets, credibly integrate ESG and other long term factors in their investment process and be responsible stewards of investments.

These changes will have significant implications for asset managers’ investment and client reporting teams. Those who do not engage with investee companies will find themselves on the wrong side of the Directive. To engage effectively and advise companies on issues of long-term sustainability, investors will need to bring new skillsets into their investment teams.

The European Commission summaries the challenging requirements investors will face in a Q+A on its website as: [2]

- Stronger shareholders’ rights and facilitation of crossborder voting: the new rules will make it easier for shareholders to exercise their rights. Intermediaries, such as banks, will have to ensure that they pass on the necessary information from the company to the shareholders, and vice versa. The new rules will ultimately make it easier for shareholders resident in another EU country than where the investee companies is based to participate in the general meetings of such companies and vote.

- Long-term engagement of institutional investors and asset managers: the new rules will require institutional investors and asset managers to be transparent about how they invest and how they engage with the investee companies. Through increased transparency requirements, the Directive encourages these investors to adopt more‑long-term focus in the investment strategies and to consider social and environmental issues. These new rules will be based on a ‘comply or explain’ approach. This means that if the investor decides not to comply with the rules, he needs to provide explanations why this is the case. The approach is similar as in corporate governance codes and stewardship codes. There is no requirement to reveal any confidential information.

- More transparency of proxy advisors: the new rules will require proxy advisors to disclose certain key information about the preparation of their recommendation and advice and to report about the application of the code of conduct they apply.

- Shareholders will have a “say on pay”: the new rules will encourage more transparency and accountability about directors’ pay. Shareholders will have the right to know how much the company’s directors are paid and they will be able to influence this. This will guarantee a stronger link between pay and performance.

- Related party transactions: the new rules will require companies to publicly disclose material related party transactions that are most likely to create risks for minority shareholders at the latest at the time of their conclusion. Companies will also have to submit these transactions for approval of the general meeting of shareholders or of the board. [3]

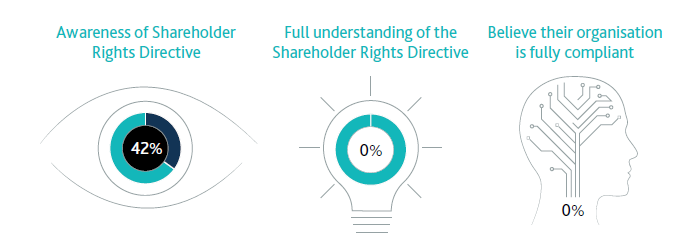

However, Hermes research suggests investors remain poorly informed and under-prepared for these paradigm shifts with just over half (58%) of participants aware of the Directive. This may seem low, but of greater concern is the finding that just 3% of total respondents believe their organisation already meets all the requirements of the Directive, suggesting significant and rapid strategic business changes will be required. There is a real danger that the lack of understanding and awareness reported in our survey will result in the Directive failing.

In our survey, we observed a strong correlation between those who show greater awareness of the new rules, and those who believe they do not meet the requirements. It seems the more people are aware of the Directive and what is expected of them, the less they believe they currently comply or could do so within a reasonable time period. Conversely, those who have a more limited understanding assume that they already comply and appear not to realise the significant steps they will need to take.

Whilst our survey found confusion amongst respondents around their roles and developing responsibilities, it is encouraging to see that the industry recognises the importance of ESG issues and concerns. Overall, more than two-thirds (68%) believe that companies which focus on ESG factors produce better long-term returns. This represents an upsurge from 48% of investors who were asked the same question in 2017, [4] however given the increased prominence of ESG in some investors’ marketing literature, a cynic may question why it is not higher.

That said, it is clear that many asset owners and asset managers are supportive of the goals of the Directive. Over a third (37%) of respondents claim to be frustrated with capital markets putting pressure on companies to deliver on short-term performance goals to the potential detriment of their long-term business needs. Many also cited compliance failures such as bribery and corruption, emissions cheating and money laundering amongst the issues causing the greatest frustration (23%).

With this in mind, most respondents hope the Directive will improve both the quality and level of shareholder engagement (66%) and lead to greater transparency across the system.

Germany

Eurosif, a pan-European sustainable and responsible investment membership organisation, identifies Germany as a leader in SRI investing [5] and our research found that 73% of German participants believe that consideration of ESG factors is part of their organisation’s fiduciary duty, the highest of any surveyed country. This is mirrored in the level of awareness of the imminent amendments to the Directive, which at 88%, is also the highest we surveyed. It seems this awareness has been supported by the fact that the German government has already issued draft legislative text.

The Directive strongly aligns with local investor interests—transparency, a focus on ESG and a move away from short-termism. German respondents expressed particular frustration with the shorttermism of markets (44%), with directors’ pay and compliance failures scoring lower (22%). The most important outcomes for German investors from the Directive would be increased transparency from companies on the process of exercising shareholder rights.

However, despite high levels of awareness and a broad acceptance of the Directive’s objectives, 70% of German investors currently do not fully meet its requirements and will need to usher in significant changes to comply with national legislation. It is interesting to note that just over a quarter (26%) of German respondents do not know if their organisation is compliant. This again illustrates the finding that the greater the awareness and understanding, the more investors realise the steps that they may need to take in order to comply.

In our view, however, the draft legislation in Germany could leave a significant implementation gap. As it currently stands, investor engagement could lack the breadth and depth required to have an impact and in effect be limited to the publication of a brief policy statement and cursory reporting.

A supporting stewardship code is needed to clarify the requirements on engagement implementation and reporting. A binding rather than advisory vote on remuneration policy at least every three years, complemented by an advisory vote on the remuneration report annually, would also be welcome. This would enable those investors who do not already engage with investee companies to play a role in containing executive compensation and aligning pay with long-term performance.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands has one of the longest standing stewardship codes, which came into effect on 1 January 2012 as Dutch corporate governance forum Eumedion published its ‘Best Practices for Engaged Share-Ownership’. This stewardship code has recently been updated and from 2019 onwards, Dutch investors are expected to report on their compliance with the principles of a new code. There is already a well-established responsible investment strategy and culture in the Netherlands; over 80% of pension funds actively engage with companies. [6]

In October 2018, the Dutch government issued draft legislative text on the transposition of the revised Directive. It is expected that a number of amendments will be made to the draft bill in the course of the legislative process, particularly in relation to executive remuneration. The Netherlands’ aim is to implement in line with current practice and to choose the options that reduce the additional burden for small-and mid-cap companies.

Respondents from the Netherlands showed a high awareness of the Directive, at 79%. Their strongest priority in terms of the Directive’s outcomes was increased transparency about the process through which shareholder rights are exercised (82%). However, they displayed the highest score for not understanding what was expected of both asset managers (50%) and companies (41%) to meet the requirements. No respondents from the Netherlands said their organisation already fully met the requirements, however 64% did claim to be mostly compliant. High awareness levels combined with a lack of compliance readiness indicate that Dutch asset owners and investors are cognisant of the major task at hand.

Dutch respondents are also well-aligned with the purpose of the Directive: 73% said companies that focus on ESG issues—and corporate governance in particular—produce better long-term returns for investors. Over half (58%) see ESG considerations when investing as part of their fiduciary duty. Compliance failures, such as bribery and corruption, emissions cheating or money laundering (36%), were the most significant frustrations for respondents from the Netherlands.

Italy

If investors in the Netherlands and Germany are positively embracing ESG, then Italy appears to be a laggard in responsible investing. Only 19% believe that considering ESG factors should be a part of their organisation’s fiduciary duty, less than half that of any other country we surveyed. Our research shows that Italian investors still have a long way to go to meet the Directive’s requirements and there is an urgent need to educate the market on the integration of engagement, ESG and long-term sustainable investing.

Italy has had a stewardship code in place since 2016, but this has not gained much traction or prominence. The growing interest in voting and shareholder behaviour in recent years has stemmed from a highly visible spike in activism in the market, while long-term focused engagement still remains an underused tool for responsible investment.

That said, even in Italy, short-termism in markets remains a real concern, cited by 48% of respondents. Our research also found that increased transparency from companies on the process of exercising shareholder rights (76%) and from investors on voting behaviour (80%) were most frequently cited as important outcomes.

Despite Italy’s government issuing draft legislative text, Italian respondents display relatively low levels of awareness (36%) of the Directive. Not one participant responded ‘yes’ when asked whether their organisation already met all the requirements of the Directive. The country also had the highest percentage who declared they did not know if their organisation met the requirements or not (68%) supporting our view that governments urgently need to raise awareness and clearly communicate specific requirements to initiate real reform.

Spain

Awareness of the Directive is low in Spain at just 42%, despite a public consultation which ran until July 2018. At the same time, Spanish investors also have the lowest understanding of the Directive of any country surveyed. A great deal of action is required from Spanish regulators as no investors believe they are already fully compliant and only 8% say their organisation mostly meets the requirements of the Directive.

93% of Spanish participants are unsure of the measures they need to take to comply with the requirements in the future. This presents a significant implementation risk and a potential lost opportunity for the country if the Directive remains a low priority for the new government. Spain does not currently have a stewardship code in place. Given the poor levels of understanding and compliance with the Directive’s requirements, Spain is clearly a laggard compared with its European counterparts.

In terms of outcomes, Spanish respondents are focused on a better quality and quantity of long-term shareholder engagement and are most frustrated by the pressure on companies to deliver short-term performance to the potential detriment of long-term performance (44%). Lack of transparency is also seen as a problem, but excessive executive remuneration and compliance failures do not feature highly as areas of concern.

In our experience, Spanish investors have shown little inclination to use engagement, preferring integration and exclusion. Most recognise the importance of ESG issues in driving long-term returns, with 67% saying it will produce better outcomes for investors. Around half (52%) see consideration of ESG factors as part of their fiduciary duty.

UK

The UK has been a leader in ESG investing, driven by the increasing priority placed on ‘fiduciary duty’. This has seen the government take action in 2018, announcing it will embed climate change and other environmental, social and governance considerations into law for trust-based pensions, plus a forthcoming FCA (Financial Conduct Authority) consultation on embedding these same considerations into rules for contract-based pension schemes. There have also been legal warnings to some large pension schemes regarding how they consider climate risk.

Surprisingly awareness of the Directive is low in the UK, at 45%. Only 8% believe their organisation already meets all the requirements and almost half (47%) do not know either way. This could be reflective of the fact that regulators have only recently clarified what is covered by the stewardship code and what needs to be added in order to meet the Directive’s requirements. These issues are being resolved through the updated stewardship code.

UK asset owners and managers are particularly concerned about the short-term nature of markets, and this is their key priority as the Directive is implemented. The update to the UK stewardship code, which was out for consultation in January, also seeks to address this and will look to create a higher tier of stewardship practice above the amended Directive.

Some UK investors see ESG as an ethical consideration rather than a means to achieve higher financial returns. As such, only 47% believe that companies which focus on ESG issues—and corporate governance in particular—produce better long-term returns for investors. This was the lowest score of any country, and is surprising given the progress made by policymakers to address the perception that a focus on ESG means sacrificing returns. We have recently seen UK investors engage more on climate change and green finance specifically, driven by political focus over the past two years. It could be that UK investors believe corporates that focus on climate change issues produce better long-term returns, but have not yet bought into the materiality of other ESG factors.

Looking Further Afield

While the Directive focuses on European member states, investors across the globe face enhanced scrutiny on how they integrate stewardship and non-financial considerations into investments.

In the United States the tide is turning and in the absence of political imperative, some institutional investors are leading by example by establishing the Investor Stewardship Group in 2018 which represents in excess of $31 trillion in US equity markets. [7] It is a significant step forward in the evolution of corporate governance and investors’ role therein in the US and an encouraging indication that the concept of stewardship is growing. However, without the impetus of regulatory action, any voluntary compliance in the US with the Directive will only ever be limited.

Japan and its sophisticated and large financial services industry was the first country in Asia to introduce a stewardship code in 2014. Other countries in the region have followed suit, however, stewardship is challenging due to regulatory issues and cultural differences including ownership structures and cross-shareholdings. Creation of a stewardship culture does not simply happen overnight and it will take years of continuous proactive investor-led engagement in the region.

European asset owners and managers must feel confident that in order to meet the requirements of the Directive, they are investing via managers who can evidence their work beyond the EU’s borders. Overseas, the impetus will be on international investors to engage with local companies and provide private sector leadership on issues of best practice corporate governance, behaviours and cultures.

It is clear from the results that asset owners, asset managers, member states and relevant regulators have more work to do on understanding and implementing the Directive if we are to reap its envisaged benefits by achieving its objectives, namely more sustainable European companies and ultimately economies. In our view, this research illustrates a disconnect in some European countries and as a result, investors across the continent are in the dark and unable to start addressing compliance gaps.

The Directive represents a historic opportunity to address some of the systemic problems in capital markets and ensure a more sustainable capitalism functioning in a fairer and more transparent way in the interests of all stakeholders.

Will the introduction of the Directive help repair the trust previously eroded in the asset management industry? Time will tell, but unless asset owners and managers take heed of its learnings one thing is for certain; our industry will never fulfil its potential to change society for the better.

Endnotes

1https://oeilm.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil-mobile/summary/1493415?t=d&l=en(go back)

2European Commission—Fact sheet, Shareholders’ rights directive Q+A, 14 March 2017 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-592_en.htm(go back)

3European Commission—Fact sheet, Shareholders’ rights directive Q+A, 14 March 2017 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-592_en.htm(go back)

4https://www.hermes-investment.com/ukw/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2017/10/Hermes_responsible_capitalism_paper.pdf Responsible Investing: The persistent myth of investor sacrifice, Hermes Investment Management, October 2017(go back)

5Eurosif—European SRI Study 2018(go back)

6Eurosif(go back)

Print

Print