Martin Garcia Mortell is Director of European Research and Cian Whelan is an analyst at Glass, Lewis & Co. This post is based on a full paper by Glass Lewis that includes market overviews and company examples for Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain & Iberia, and Switzerland.

Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here).

Introduction

While the progress of integrating environmental and social (“E&S”) factors into the corporate governance activities and reporting of publicly listed entities faces sudden and significant headwinds in much of the world, the EU is increasingly turning words into action. Partly in response to developments in this area, Glass Lewis have codified our approach to reviewing how boards are overseeing environmental and social issues. For companies listed in a blue-chip index and in instances where we identify material oversight issues, Glass Lewis will review a company’s overall governance practices to identify which directors or board-level committees have been charged with oversight of environmental and/or social issues. Across the EU, we are seeing corporate governance increasingly incorporate the idea of stewardship—that the corporate governance of an issuer should include the governance of environmental and social risks and opportunities. Yet, within this broad trend, issuers are implementing market practice in a wide variety of ways.

Since its earliest iterations, the various stakeholders involved in corporate governance have recognised that a one-size-fits-all approach is of limited benefit. The success of comply-or-explain, and the consequent emphasis of the role of disclosure in facilitating dialogue, are good examples of how it is impossible to develop an understanding of corporate governance by simply reading a codified list of best practices. Corporate governance is at heart a conversation, the product of a collection of stakeholders with varying interests and expectations that can only align through meaningful dialogue. And in order to understand any conversation, context is key. To understand the environmental and social governance arrangements of any individual entity in the UK and European markets, you must first understand the context they are operating in.

In 2010, the EU published a new economic strategy designed to guide the EU member states out of the global financial crisis and prepare their collective economies for the next decade. The 2020 Europe Strategy placed an increased emphasis on the sustainability of businesses, and the role of EU-level company law in improving the business environment. The EU’s 2011 Green Paper on Corporate Governance formed part of this strategy, identifying, among many areas of improvement, the board’s role in risk management in promoting the sustainability of companies’ business activities. An Action Plan followed in 2012, which gave rise to the second iteration of the Shareholder Rights Directive in 2017. The Shareholder Rights Directive II placed non-financial factors, particularly environmental, social and corporate governance, front and centre in terms of company reporting, shareholder engagement, and executive pay. Separately, the recommendations of the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance formed the basis of the 2018 Action Plan on Sustainable Finance, which identified a need for companies to transparently disclose their governance of environmental and social risks and opportunities.

While the succession of increasingly focused strategic initiatives suggest a single EU-wide story, issuers have been interpreting and implementing their governance of environmental and social factors in a much more diverse and diffuse manner. The EU provides a high-level framework, however, each issuer operates in a unique context that reflects local market realities. In this paper, we give an overview of the relevant market-specific legislation and regulations that provide the contexts for individual companies’ various governance approaches to managing the risks and opportunities offered by environmental and social factors. We provide case studies that are indicative of each market’s collective response to this growing sub-set of corporate governance. Finally, we consider how this overview can inform the conversations between investors and issuers, and areas for future dialogue and collaboration.

United Kingdom

Corporate governance practices in the UK are primarily based on the UK Corporate Governance Code (the “UK Code”), which is maintained by the Financial Reporting Council (“FRC”). The UK Corporate Governance Code operates on a comply or explain basis, meaning issuers have the option of deviating from the code provided a sufficient rationale is provided; however, the Code is widely regarded as a codification of best practice in the market, rather than a utopian ideal removed from the realities of business, so the vast majority of issuers voluntarily comply in full with the Code’s recommendations.

The UK Code is supported by a number of supplementary guidelines, which are designed to stimulate thinking on how boards can carry out their role and inform their actions and decisions in applying the Code’s Principles.

The 2018 Guidance on Board Effectiveness identifies the consideration of the company’s long-term success and future viability as a key responsibility of an effective board. In this context, the FRC suggests that a board may find a commonly understood framework, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures, useful for informing and communicating business strategy. The 2018 Guidance on the Strategic Report suggests that information on environmental, employee, social, community and human rights matters should not be considered separate to the other elements of the report, but integrated throughout, including in relation to the company’s strategy and business model, risk management and KPIs.

Our review of the FTSE100’s governance of environmental and social risks and opportunities has found that UK blue-chip issuers use a variety of approaches to implementing the FRC’s recommendations. Examples abound of full board accountability, stand-alone E&S committees, individual directors and senior executive teams with ultimate responsibility for the identification of environmental and social risks and opportunities.

Below we discuss some of the largest companies in their respective sectors and provide examples of the variety of approaches available to issuers for governing environmental and social risks and opportunities.

HSBC

HSBC is one of the largest financial services and banking organisations in the world, with a sprawling network of operations across 70 countries. HSBC has a chequered corporate governance history: it has been involved in a number of high-profile controversies, including allegedly facilitating money laundering for Mexican drug cartels, but it has also been consistently at the forefront of adopting best practice as it develops. For example, when the Bank of England announced in 2017 that it was considering incorporating climate scenarios into its normal prudential activities, HSBC was the only UK bank to include any mention of climate scenarios in its annual report. In 2018, HSBC reported according to the recommendations of the TCFD, wherein it identified climate scenarios as an area of focus for 2019.

What is the oversight structure?

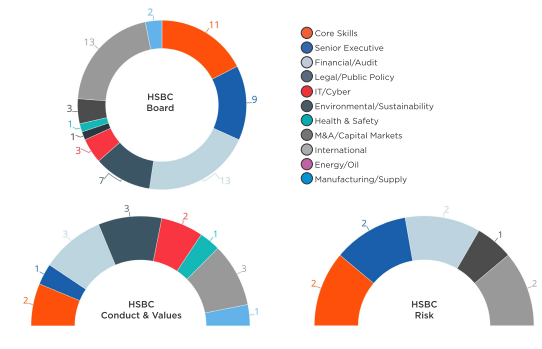

Perhaps reflecting the multi-faceted dimensions of its business, HSBC has a myriad of risk-governance related committees. The Group Risk Committee has non-executive responsibility for the oversight of enterprise risk management, risk governance and internal control systems, with particular emphasis placed on its role as a collaborator with the Group Audit Committee on areas of mutual overlap. The Financial System Vulnerabilities Committee oversees matters related to financial crime and system abuse, anti-money laundering, terrorist financing, corruption and cybersecurity. The Philanthropic & Community Investment Oversight Committee is responsible for HSBC’s philanthropic and community investment activities in support of its corporate sustainability objectives. And the Conduct & Values Committee has non-executive oversight of culture and conduct risk, including reviewing how effectively the company is meetings its sustainability commitments.

Are there board members with E&S experience?

Takeaway

Environmental and social risks and opportunities are wide ranging and diverse in their nature and materiality. HSBC provides an example of one method for governing these dimensions of a business: a variety of specialised committees. For stakeholders who are assessing HSBC’s governance of E&S, it might be helpful to consider the skills make-up of each committee, and whether cross-committee memberships or other structures are disclosed to ensure that information isn’t siloed between each specialised committee.

Diageo

Diageo is a global producer of branded alcoholic beverages. With a presence in over 180 countries, including mature and emerging markets, Diageo necessarily faces a broad range of potential environmental and social risks and opportunities. Diageo’s Sustainability & Responsibility Strategy is aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and contains measurable targets to be delivered by 2020.

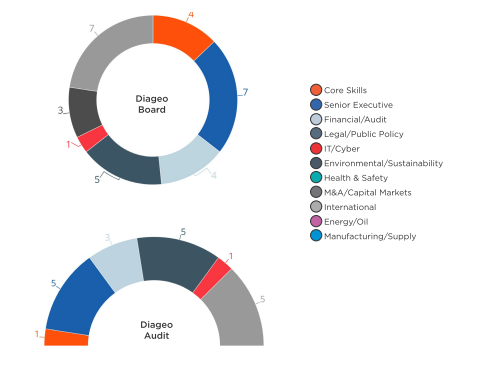

What is the oversight structure?

Diageo’s Chief Executive, Ivan Menezes, is ultimately accountable for overall performance against sustainability and responsibility goals and 2020 targets, while responsibility for the component parts of its Sustainability & Responsibility Strategy is shared between members of the Executive Committee. In its disclosure on identifying and managing economic, environmental, and social impacts, Diageo states that while the Chief Executive and the Executive Committee are ultimately accountable for sustainability performance, the Sustainability & Responsibility Strategy is discussed at board level and incorporates stakeholder consultation where possible. Further, Diageo states that in some cases members of the board have identified new economic, environmental and social impacts that Diageo should manage. The Audit Committee also discusses risks, including environmental and social risks, at least twice a year.

Are there board members with E&S experience?

Takeaway

Developments in the corporate governance regime in the UK are placing increasing emphasis on the board’s involvement in governing companies’ responses to both risks and opportunities. In our experience, environmental and social issues are best understood as spanning a spectrum between board and management responsibility. Where a company finds itself on that spectrum will depend on its specific risk exposure along with operational and oversight structure—and regardless of where they are on the spectrum, it’s important for companies like Diageo to explain their approach in order to better inform the dialogue between all stakeholders.

AstraZeneca

AstraZeneca is a multinational pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical company, developing drugs around three main therapy areas: oncology, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and respiratory. AstraZeneca’s self-identified matrix of material sustainability issues is extensive and diverse, including: workplace health and safety; biodiversity; ethical sales and marketing; and climate change.

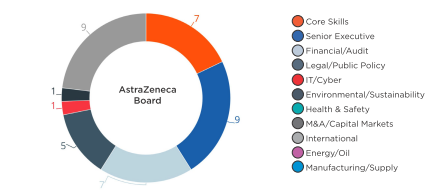

What is the oversight structure?

AstraZeneca’s governance of sustainability brings together a mix of executive, non-executive, and external participation. Non-executive director Geneviève Berger oversees the implementation of sustainability matters on behalf of the board of directors. Each member of the senior executive team (SET) is accountable for a specific sustainability target. The Sustainability Advisory Board (SAB) comprises five SET members and four external sustainability experts. The SAB met once in 2017 to approve strategic direction, recommend opportunities and provide external insight and feedback.

Are there board members with E&S experience?

Takeaway

As a global biopharmaceutical company, AstraZeneca is highly exposed to environmental and social risks and opportunities. While other FTSE 100 companies emphasise the board’s involvement in governing E&S, AstraZeneca stands out for emphasising how its governance includes a diverse mix of both internal and external elements. Where the relationships between a company and its environmental and social factors are highly complex, AstraZeneca’s approach provides an example of utilising external expertise to supplement the board’s oversight.

Considerations for Issuers

Defining E&S

Perhaps more than any other area of corporate disclosure and investment decision-making, the language around environmental, social, and corporate governance is endlessly debatable and subject to radically different interpretations. Indeed, the acronmyms “E&S” and “ESG” are often used interchangeably. Previous studies have drawn distinctions between, for example, ethical investing, impact investing, responsible investing, corporate social responsibility, and integrating ESG. The recent developments in creating an EU-wide taxonomy for sustainable finance will go some way towards putting corners on this debate, but ultimately it is up to issuers and investors to engage in meaningful dialogue to ensure their language is aligned. From the issuer’s perspective, this means reflecting on the implications of their language decisions. For example, the name of the committee with delegated responsibility for environmental and social risks and opportunities: stakeholders will have different expectations of an Ethics Committee compared to a Sustainability Committee compared to an Audit Committee with oversight of environmental and social reporting. A mindful use of language, and meaningful disclosure that makes the assumptions implicit in language use explicit, is an important contributing factor to efficient and productive dialogue.

Composition and skillsets

Related to the point on definitions, wherever there is a unique lexicon constructed for the purposes of clarity, there will always be people who utilise that lexicon to obfuscate rather than reveal. Buzz phrases and boilerplate language are rife in conversations about E&S, but they become more easily identifiable as such when the people involved are skilled in the area. Regardless of the particular governance arrangement put in place by an issuer, the people involved ought to have the relevant skills and background to be able to cut through the buzz and get to the material issues to be discussed.

A good parallel example of this issue is IT and cybersecurity. In our conversations with issuers, we are hearing that they don’t just want one token IT-expert; instead, all executives and board directors need to have IT training to stay on top of their risk management role in this fast-moving area. The intense media coverage and immediate, direct consequences around data leaks are making issuers take this issue particularly seriously; if a similar attitude is taken to environmental and social factors then investors should expect clear rationale for not just the particular governance framework an issuer chooses, but also for their decisions as to the individuals involved. Essentially: why are these people particularly well suited to navigating the rapidly developing landscape of environmental and social risks and opportunities?

Why governance? Robustness and measurability

As the conversations about environmental and social risks and opportunities grow ever more mature and complex, there is a growing requirement to sort out the signal from the noise. One of the main challenges for issuers is putting corners on their environmental and social issues, identifying the truly material factors and communicating that to all stakeholders. Looking to an issuer’s governance of these issues provides many advantages. While environmental and social issues are relatively new and ever-evolving concepts, corporate governance has a long history and stable vocabulary. Corporate governance processes cover a spectrum, with boilerplate one-sentence disclosures at one end and genuinely evolving lines of accountability at the other. Whether a given process is relevant and sufficient can be a matter of debate—hence the importance of engagement between all stakeholders on an on-going basis—but where an issuer has appropriate governance processes in place, it gives some indication of their readiness to deal with each new twist the E&S field throws their way. In our experience, an issuer’s governance of environmental and social risks and opportunities needn’t stray from already established best practices: clear lines of accountability, ownership of each successive level of involvement, independent oversight, and measurable objectives inextricably linked with company strategy. Whatever approach an issuer takes in response to its unique risk profile and market-context, the robustness of its governance in these areas provides a sound foundation for continuous dialogue and engagement.

Print

Print