Wes Hall is Executive Chairman and Founder, Amy Freedman is Chief Executive Officer, and Ian Robertson is Executive Vice President of Communication Strategy at Kingsdale Advisors. This post is based on a their Kingsdale memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); Dancing with Activists by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch(discussed on the Forum here); and Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Momentum is building for M&A across the gold industry driven by the market, balance sheets, and shareholders. Behemoths Barrick Gold Corp. (NYSE: GOLD, TSX: ABX) and Newmont Mining Corp. (now Newmont Goldcorp Corp. (NYSE: NEM, TSX: NGT)) have grabbed headlines with acquisitions of Randgold Resources Ltd. and Goldcorp Inc. respectively, and the junior and intermediate space has seen a flurry of deals as well.

At the same time, shareholders have launched high profile campaigns against Detour Gold Corp. TSX:DGC), Guyana Goldfields Inc. (TSX:GUY), and Hudbay Minerals Inc. (TSX, NYSE: HBM), an integrated mining company with some exposure to gold that is nonetheless instructive, with part of the shareholders’ thesis for change related to the viability of M&A opportunities.

In fact, in the last two quarters (Q4 2018 and Q1 2019) we have seen over CAD$20 billion in deals announced in the gold industry involving Canadian listed companies [1] and 13 activist campaigns in the last 26 months, with activists scoring wins or partial wins in all but three contests. (And these are only the activist actions that we know about; based on our experience only a fraction of activist interactions ever become public.) We would note specifically that the three management wins all came at small companies while the activist wins came at relatively large companies, demonstrating that size is not a defence.

Both potential acquirors and shareholders are seeing a new age of opportunity dawning.

After years of increased financial discipline, cutting costs and prudent capital spending, many companies have stronger balance sheets. Couple with this the need to demonstrate long-term growth and value creation to investors, acquirors, and shareholders looking to prompt an acquisition are primed for action.

Unlike acquisitions of the past which were often motivated by the potential of increased gold production or diversification, recent M&A deals have focused more on capital efficiency and operational excellence, with the management team being one of the assets (or liabilities) evaluated. With the finite life of a mine, geographical dispersion of mining activities, significant capital commitments, diminishing production, and tightening post-peak production margins, companies are turning to M&A as a means to ensure long-term resource replenishment, capital efficiency, and as a way to smooth out portfolio hiccups.

A new theme that has emerged from the focus on operational excellence—as pivotal in driving value and margin improvement—is the “at-market” or premium-less deal as used in the Barrick-Randgold merger and central to Barrick’s unsolicited attempt to block the Newmont-Goldcorp deal. The argument being put forward to shareholders was “your premium is the future value created and synergies”. Although not uncommon in a merger of equals, it is an interesting development for mergers of what may be considered un-equals.

Additionally, we have seen a shift away from a “size for size’s sake” mindset to owning and focusing only on the best assets. A by-product likely to follow will be more non-core asset sales or increased joint venture or partnering arrangements.

For those companies who have not yet made a deal—and their shareholders—the question is what should be done to avoid being left behind or missing an opportunity to grow or diversify the company’s portfolio?

With the giants of the industry growing, pressure will increase on others to improve as well, recognizing the need for rationalization and scale. Gold investors who have suffered through years of value destruction, failed acquisitions, mismanaged permitting, misaligned compensation schemes, over-optimistic or ill-conceived life of mine plans, and strings of missed guidance, are skeptical and have put management teams on short leashes when it comes to value creation.

Many in the industry will admit there is fragmentation in the space but commonsense deals (from a shareholder perspective) where assets might be adjacent to one another are too easily dismissed because management is interested in preserving their jobs. Shareholders are coming to the conclusion that the future of gold mining is going to look very different than it did in the past but frustrated by management teams who may be slow to embrace a new ideology and unwilling to question some of the assumptions that have underpinned their long-term strategy.

Despite this clear and present danger, too many miners remain unprepared to deal with a potential activist or hostile bidder because of a mistaken, presupposed belief in shareholder support, a lack of awareness about what they could be doing proactively to prepare, or incorrectly believing they could never become a target.

Even as share prices have improved recently, directors and management cannot afford to be complacent. An improved share price can only serve to buy them time to address ongoing underlying issues that range from the operational to governance but it cannot abate a shareholder with a taste for change.

The fact is, no gold company is immune. And with a new activist campaign launching every other month (on average) the question is no longer if but when.

Why are gold companies vulnerable to activists?

The gold industry is still fraught with investor fatigue after years of share price weakness and concerns about poor operational performance and deficient governance practices.

In the early part of the decade—with gold prices nearing historic highs—North American goldminers went on spending sprees, overpaying for risky asset acquisitions that destroyed shareholder value in a significant way. Some industry-watchers have estimated that these failed deals amounted to over US$85 billion in write-downs, [2] with capital fleeing to other sectors. Meanwhile, we have observed that gold bugs and others still wanting exposure to gold without the pitfalls of owning mining stocks, moved their capital into gold royalty companies.

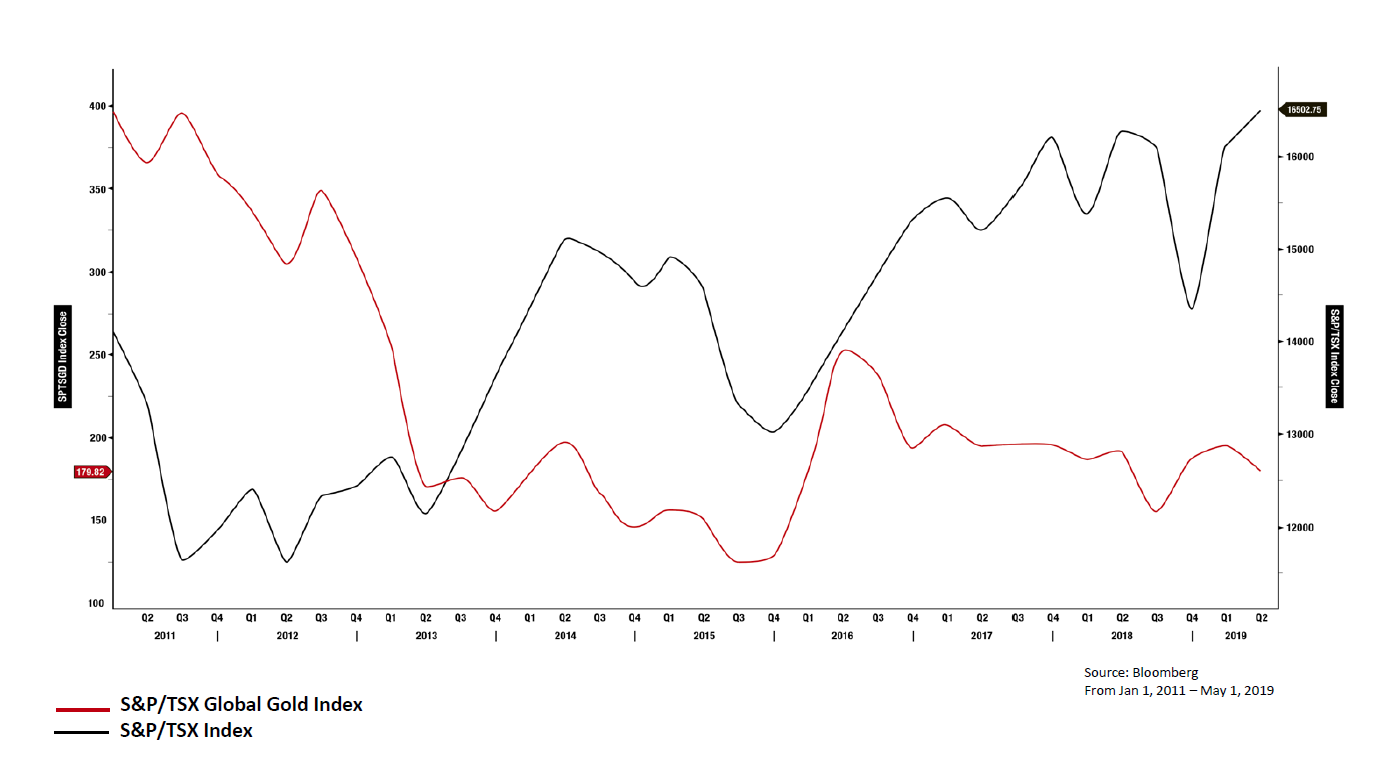

These shifts in investor interest have unquestionably been reflected in the market and we’re still feeling the impacts today. Relative to the S&P/TSX Index, the S&P/TSX Global Gold Index (SPTSGD Index) has remained at discounted levels since 2013, while the TSX Global Gold Index has lost more than 60% of its value since the highs of 2011.

During this time, Canadian gold companies have not only underperformed the markets, they’ve even disappointed when compared to the price of physical gold—which itself has been lackluster.

You can’t blame shareholders for being weary.

Share Performance Matters but Shareholders Are Also Passing Judgement on Operations and Governance

Like any fragile relationship, the relationship between directors and shareholders in the gold industry hinges on what has increasingly become two diverging perspectives.

For years we have heard shareholders voice a growing list of concerns that too many times fall on deaf ears. The continued persistence of these problems and what shareholders see as repeated and avoidable errors, either in operations or judgment, are leading more and more investors to a breaking point.

Over and over, we have heard shareholders complain—first privately and now increasingly publicly—about sustained poor performance vs. peers or the index; poor market guidance; project delays; capital overruns; inability to secure “routine” permits and negotiate licenses; and excessive compensation.

When you layer onto these frustrations a series of performance issues, concerns about boards with little to no share ownership, long tenures, “entrenchment”, and a cozy relationship between too many directors, it is no wonder that shareholders have grown restless.

On the flipside, boards have argued that shareholders need patience, a long-term view, and an appreciation of the complexities of gold mining in often unpredictable environments—both geological and political. The type of directors able to navigate through the complex challenges of today, ranging from the technological to the regulatory, are in short supply and when you have board members who really know a set of assets and their history, it is important to keep them.

Regardless, from an investor’s perspective, despite the recent upticks, there has been a dramatic sector recoil over the past several years. Put another way, investors have lost faith in the boards of gold mining companies’ ability to manage risk and are seeking out ways to push for change.

Who are the activists?

While gold shareholders with complaints are not

novel, the industry is witnessing a heightened level of scrutiny with some investors willing to spend vast amounts of time, effort, and money to fix what they see as damaged companies with boards incapable of optimizing value.

Today’s gold activists are, for the most part, unclassifiable. They can be anyone—from a well-known fund to a former insider to an average shareholder willing to organize. What they have in common is the ability to engage other shareholders, industry expertise, media savvy, and the resources and stomach to embark on a lengthy proxy contest. For the most part, these are not your short-term corporate raiders or ankle-biters. Their interests are long term; they’re not only in it for a quick lift in share price.

As history has shown, it doesn’t even matter if they have a good case for change, just that they can tap into the frustration of other shareholders. Additionally, gold fund managers that may not be activists themselves are increasingly showing support for fellow shareholders wanting to implement positive change. The lesson for directors is they cannot afford to look at a shareholder list, see no “known activists” and assume they are safe.

Enter Paulson and the Shareholders’ Gold Council

One of the shareholders leading the charge against the goldmining industry is New York-based hedge fund Paulson & Co. Inc.

Paulson’s attacks on the industry began at the Denver Gold Forum in 2017, where fund partner Marcelo Kim gave a damning presentation blaming directors and executives for the industry’s value destruction. Kim’s thesis was unrestrained by his audience of industry veterans: Major gold mining stocks, he stated, underperform both the gold price and the broader equity indices (citing the GDX and GDXJ in particular), destroying shareholder value because board members have repeatedly put their interests ahead of shareholders. The presentation provided several examples of governance deficiencies—he claimed were widespread throughout the industry—that effectuated this value gap and align with the list of concerns we noted earlier.

Of note, criticisms about a lack of board oversight and accountability garnered significant traction. Shareholders have become weary of boards who claim credit for big bounces in share price when gold prices are strong yet blame the commodity when share prices fall, ignoring continued operational failures, lack of focus on capital discipline, and inadequate focus on market guidance.

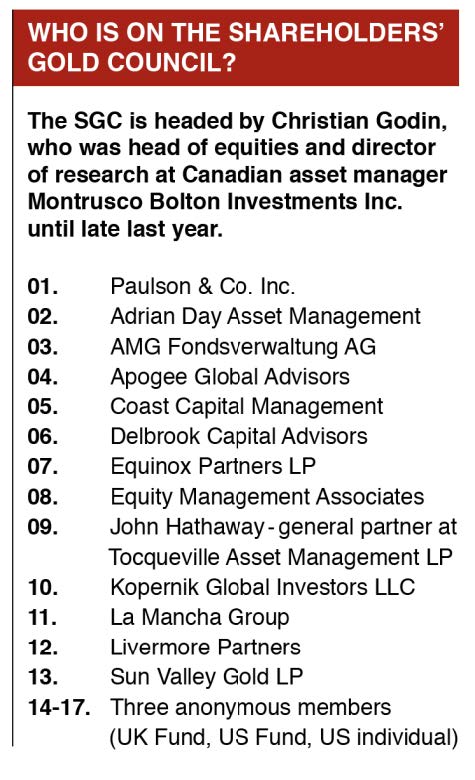

Kim’s presentation called on shareholders to unite as a means to collectively raise shareholder returns at “underperforming companies”—a list which, according to Paulson, includes every top gold mining company in North America. Subsequently, the Shareholders’ Gold Council (“SGC”) was established with its founding members consisting of institutional investors, asset managers, and an activist fund. (Based on this composition, it is clear who the council intends to benefit. Hint: not incumbent leadership at gold mining companies.)

As of publication date, the SGC has put out two missives: Its first research summary highlighted the relationship between share price and level of stock ownership of the industry’s chairs and CEO’s. In the second communication, they targeted Goldcorp’s then-CEO David Garofalo and his salary.

While some have questioned the validity of Paulson’s thesis and the motive behind the SGC (to fix a broken sector vs. a means for a hedge fund to generate quick returns), in our view Paulson’s SGC is more than just an industry forum. It is constructed to franchise out activist campaigns in the gold industry.

Miners beware.

The Opening Act: Paulson’s Campaign Against Detour Gold

On July 18, 2018, Paulson launched an activist campaign against Detour Gold, owner of Canada’s largest goldmine, that is illustrative of the likely playbook and tactics Paulson, the SGC, and other shareholders will use in future campaigns.

Paulson started its campaign calling for the company to enter a sale process. When its initial assault was rebuffed, Paulson changed its strategy to push for a whole new board of directors that could presumably facilitate a sale.

During a prolonged five-month, sometimes nasty, proxy contest, Paulson publicly touted a narrative about Detour Gold that reflected the complaints it laid out at the Denver Gold Forum: Detour Gold, it said, represented a unique asset that had been poorly managed and lacked proper board oversight as evidenced by three life of mine plans in three years. The board had been there for too long and lacked the “skin in the game” Paulson had.

While some of the alleged tactics Paulson employed caught the eye of the regulators, the hedge fund’s playbook is one that is likely to be reused to reshape the industry: Bully companies into making the changes they want and if they are rebuffed, put the company into play.

In the end, shareholders either bought into Paulson’s narrative or simply felt enough frustration to vote for change: Paulson’s slate of director nominees took control of the company’s board following a December 2018 special meeting of shareholders.

Paulson is Not Alone: Other Activists Highlighting Similar Pattern

In January, a group of concerned shareholders of Guyana GoldfieIds, led by founder and former chairman Patrick Sheridan, requisitioned a special meeting seeking wholesale board change, calling out the current board and management for a period of massive value destruction, questionable decisions, improprieties, and missed guidance. The concerned shareholders and their nominees promised a comprehensive agenda that included fixing performance issues, leading a share price recovery and executing a value-maximizing transaction. In April, Guyana Goldfields settled with the activist announcing the CEO who had been targeted would be leaving and a new board with five of seven directors replaced since the proxy fight was launched.

Another campaign, launched last October by Waterton Global Resource Management against Hudbay Minerals (again, a company with exposure to gold that is nonetheless illustrative), operated on a counter thesis—that M&A is not in the company’s best interest. The activist leveraged a familiar similar set of shareholder concerns to gain support for change: Waterton expressed a lack of confidence in the ability of the company to use M&A to create shareholder value, criticized it for sustained poor performance vs. peers, and for surpassing its worst-case permitting timelines without being upfront about or taking accountability for the delays. In May, Hudbay announced a settlement that added three Waterton supported directors to its eleven-person board.

These campaigns, along with Paulson’s attack against Detour Gold, highlight the fact that any company, no matter its profile, size, or asset base can be an activist target.

How gold companies can prepare

If there is any good news in all of this for gold companies, it is that their boards hold their fate in their own hands. While Canada’s miners cannot control commodity prices, there are proactive steps that they can take today to, at best, inoculate themselves from activist attacks and at worst, be prepared for a fight.

Here is a top 10 checklist for gold companies:

1. Engage & Understand Your Shareholders.

Knowing who your shareholders are is one thing, understanding their concerns is another. Shareholders want to know you are listening—which means demonstrating you have considered and acted on their concerns to the extent they are consistent with the company’s strategy and path to value creation. Knowing your shareholders’ priorities will help ensure their support in the event of an activist attack or hostile bidder. Communicate a compelling long-term plan, supported by data and projections, to inspire confidence in your shareholders that will protect against short-termism. Including independent directors and not just management in this outreach is important as often the message directors receive is different than what is conveyed to management—especially true if management is seen as the issue.

Where supportive shareholders are identified, prudent issuers are wise to expand their shareholder bases with “friendlier” shareholders who are aligned with the company’s long-term plan.

Decentralized voting is on the rise and companies now require a more nuanced understanding of institutional investors’ priorities to earn their votes. Institutional investors are moving away from total reliance on Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis; some firms use these recommendations as a data point to enhance their own review process, while other firms place more significance but do not automatically vote with the proxy advisors. Companies must place renewed importance on communicating with institutional investors and appealing to their unique preferences, while continuing outreach with the nonetheless influential ISS and Glass Lewis.

2. Undertake a Deep and Critical Self-Analysis.

We have outlined the issues that have shareholders up in arms and now companies need to understand how those concerns apply to them. Go beyond a simple SWOT analysis and put your company in constant state of internal review, with an eye towards identifying flash points that could attract activists: Check your balance sheet—does your company carry excess cash or debt? What is the status of your non-productive assets? Based on today’s operational data and gold price assumptions, are any assets impaired?

3. Don’t Underperform on the Things You Can Control.

Leverage to the commodity price means gold companies gain more when the gold price increases and lose more when the price decreases. It is also why missing production guidance, delayed project timelines, and mine cost overruns hurt more as they consume valuable capital and delay the all-important free cashflow.

It is important to understand that misses have a negative compounding effect on management’s reputation, as shareholders ask: if the preceding guidance wasn’t good enough, why should we trust the new one? Shareholders want to understand why you were unable to control the things you should have been able to control, why the variance, why your plan was wrong, and why they should trust you now. When market guidance is missed shareholders often face upwards of 30% share value erosion almost immediately and the market typically needs to see several quarters of met or exceeded guidance before that share value is replaced.

In the past, management has been able to use gold’s leverage to take credit for share price increases during market upturns and defer responsibility on the downturns. That era is over; management needs to be seen as building value in a down cycle by being proactive on securing social license, investing in technology and processes to drive down all-in-sustaining-costs (AISCs), increasing reserves, while remaining prudent on capital decisions by setting stringent hurdle rates for capital investment.

4. Preempt Attacks by Installing Appropriate Structural Defences.

Assess if your defence mechanisms are up to date and proxy advisor (ISS and Glass Lewis) compliant. Adopting or bolstering advance notice provisions, rights plans, and other legal tactics, is critical.

5. Ensure Alignment with Shareholders.

Pay-for-performance and Performance Share Units (PSU) initiatives remain the best way to hold board members accountable and align their goals with shareholders’ goals. Total Shareholder Return (TSR) also remains a popular vesting criterion due to its objectivity and simplicity. In a leveraged industry where critics accuse management of hiding behind commodity prices, these measures reinforce management’s commitment to shareholder value and to solid performance at all stages of the mining lifecycle. Fundamentally, if the share price does not consistently reflect management’s contribution, one of two things is wrong: Either management is focusing on the wrong things or they are not communicating and guiding the market appropriately—both of which need to be addressed.

6. Ensure the Right Directors for the Right Time.

Shareholders view an ongoing commitment to board refreshment as an indication the board has the up-to-date technical expertise and fresh thinking it needs. Companies will have their ISS QualityScores negatively impacted if more than one-third of their board has a tenure of nine or more years and some shareholders have even more stringent views.

Companies should expect similar skepticism towards board members who have known the CEO personally or professionally for extended periods of time and may allow (or appear to allow) this relationship to impact their judgement and compromise their independence.

In an age of heightened scrutiny coupled with increased shareholder engagement, it is critical to ensure board members understand enough from a technical perspective to question the company’s strategy and act as a critical eye. Having directors experienced in each stage of the mining lifecycle can align with prudent refreshment timelines. Directors with exploration and development experience may be supplemented or replaced with mine builders and operators at the right time to ask the right questions of management. Likewise, directors who bring diverse backgrounds to the board are likely to ask the tough questions from the outset, as they do not take anything for granted.

7. Accountability Matters. Demonstrate Oversight and Leadership from the Top.

As we have outlined, shareholders are concerned about a steady stream of misses that, in their view, should have been avoided. Boards should recognize the perception that geologists who work in-house have an incentive to confirm management’s suspicions about the presence, quantity, and grade of gold in a proposed mining site.

Boards should consider taking steps to avoid even the appearance of bias. Knowledgeable boards that can question life of mine plans enhance overall accountability, but boards need to take it one step further. If results fall short of guidance, management needs to do more than just state the discrepancy. They need to state why they were wrong, why shareholders should trust the new plan, and how the company will modify processes to avoid making similar errors in future. This is crucial in a down cycle, where missing production guidance, delayed project timelines, and mine cost overruns are amplified. We know mining is not a perfect science and “stuff” happens—but you must fall on your sword where needed and then get back up with a thesis of how you will continue to persevere.

Boards need to ensure a balance of expertise so they are not only able to question life of mine plans effectively but to adequately evaluate management to ensure they get their number one job right: Hiring the right CEO (and firing the old one if needed).

8. Appearance Matters More. A Spotless Governance Report Card can Make a Big Difference.

Governance issues, or perception of governance issues, provide low hanging fruit for an activist as the failure to address basic governance concerns is used as evidence that at best a board doesn’t care and at worst is self-dealing. Increased focus is being placed on topics like related party transactions, interlocking relationships, overboarding, and diversity. Importantly, much of ISS’ and Glass Lewis’ evaluations will rest on governance. In addition, recent proxy fights have shown that shareholders don’t view PSUs and Deferred Share Units (DSU) as true share ownership.

Shareholders want their directors to buy and own actual shares, just like they do.

9. Understand Timing Matters.

It is important to understand how the proxy advisors will evaluate you and what that could mean for an activist attack. As a starting point, proxy advisors often evaluate companies based on their 1, 3, and 5-year TSRs against peers. This emphasis on short-term thinking and data presentation can be misleading when it comes to gold mining as mines run long-term projects that can take up to a decade to produce lucrative returns. Most gold companies have languished under these timeframes, but the degree of value destruction is relative as much of it comes from factors that impact the entire industry, such as the gold price. In addition, the lack of capital resulting from high-risk investors shifting to royalty stocks, cannabis, blockchain, and other new sectors will impact any recent TSRs.

While TSR performance is set in stone, especially when it comes to 3- and 5-year reports, management can take steps to counteract the image that these reports portray. Specifically, they can institute turnaround measures and improve operating metrics to show that, despite previous performance, your board is on task and committed to increasing execution.

10. Proxy Fights are No-Holds-Barred: Prepare for Reputational Damage.

The gold industry is made up of a close-knit group of professionals and with that comes the knowledge of what directors and management have been up to. Longstanding relationships mean that peers have more information about others, such as how X acted in a private board meeting or the strategy that Y proposed that bankrupted a past private company. It is important to understand that any individual can weigh-in with a fact or comment, whether it’s fair or fabricated. Since negative comments cannot be taken back, litigation will do little to remedy the situation and pursuing a claim can make you look guilty. Even with the gold industry’s connectedness, your effort is still better spent playing for the persuadable voters, targeting select opinion leaders, and focusing on your execution.

For directors on gold company boards, whether they agree with the views of activists and the shareholders who back them is irrelevant. What is relevant is that a growing series of circumstances that they may or may not be able to control are conspiring against them to create an irrefutable case for change.

The question then is will you let that change sweep over you or will you drive that change?

Endnotes

1Based on data sourced from Bloomberg(go back)

2http://www.mining.com/web/disastrous-deals-sideline-gold-mining-ma-metal-rises/(go back)

Print

Print